Operation Starlite

Operation Starlite (also known in Vietnam as Battle of Van Tuong) was the first major offensive action conducted by a purely U.S. military unit during the Vietnam War from 18 to 24 August 1965. The operation was launched based on intelligence provided by Major general Nguyen Chanh Thi, the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) I Corps commander. III Marine Amphibious Force (III MAF) commander Lieutenant General Lewis W. Walt devised a plan to launch a pre-emptive strike against the Viet Cong (VC) 1st Regiment to nullify their threat to the vital Chu Lai Air Base and Base Area and ensure its powerful communication tower remained intact.

| Operation Starlite | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Vietnam War | |||||||||

Vietcong prisoners (or civilians) await transport during Operation Starlite | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

LG Lewis W. Walt Col. Oscar F. Peatross |

Lê Hữu Trữ (commanding officer) Nguyễn Đình Trọng (commissar) | ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

3rd Battalion, 3rd Marines 2nd Battalion, 4th Marines 1st Battalion, 7th Marines 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines 3rd Battalion, 12th Marines |

1st Regiment 52nd Company One company of the 45th Weapons Battalion | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 5,500 | ~1,500 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

45 killed Viet Cong claim: 919 killed and wounded |

U.S body count: 614 killed 9 captured 42 suspects detained 109 weapons recovered Viet Cong report: 200-300 killed, wounded or captured[2] | ||||||||

The operation was conducted as a combined arms assault involving ground, air and naval units. U.S. Marines were deployed by helicopter insertion while an amphibious landing was used to deploy other Marines. The VC used a variety of tactics to counter the Marine assault, fighting from prepared positions and then withdrawing as the Marines gained local superiority and ambushing a lost supply column. The VC were unable to withstand the weight of the Marine assault and U.S. firepower losing 614 killed and nine captured for U.S. losses of 42 killed.

Background

The United States had been providing material support to South Vietnam since its foundation in 1954. The Vietnam War effectively began with the start of the North Vietnamese backed VC insurgency in 1959/60 and the U.S. increased its military aid and advisory support to South Vietnam in response.[3]: 119–20 With the worsening military and political situation in South Vietnam, the U.S. increasingly became directly involved in the conflict.[3]: 131 U.S. Marines were the first ground troops deployed to South Vietnam, landing at Da Nang on 8 March 1965.[3]: 246–7 In May the Marines and ARVN forces secured the Chu Lai area to establish a jet-capable airfield and base area.[4]: 29–35

On 30 July, COMUSMACV General William Westmoreland told III MAF commander General Walt that he expected him to undertake larger offensive operations with the South Vietnamese against the VC at greater distances from his base areas. Walt reminded Westmoreland that the Marines were still bound by the 6 May Letter of Instruction that restricted III MAF to reserve/reaction missions in support of South Vietnamese units heavily engaged with a VC force. Westmoreland replied "these restraints were no longer realistic, and invited Walt to rewrite the instructions, working into them the authority he thought he needed, and promised his approval." On 6 August, General Walt received official permission to take the offensive against the VC. With the arrival of the 7th Marine Regiment a week later, he prepared to move against the 1st VC Regiment.[4]: 69

In early July, the 1st VC Regiment had launched a second attack against the hamlet of Ba Gia, 20 miles (32 km) south of Chu Lai. The ARVN garrison was overrun, causing 130 casualties and the loss of more than 200 weapons, including two 105 mm howitzers. After the attack on Ba Gia, US intelligence agencies located the 1st VC Regiment in the mountains west of the hamlet. Reports indicated that the regiment was once more on the march. Acting on this intelligence, the 4th Marine Regiment conducted a one-battalion operation with the ARVN 51st Regiment, 1st Division in search of the 1st VC Regiment south of the Trà Bồng River. Codenamed Thunderbolt, the operation lasted from 6 to 7 August, and extended 7 km south of the river in an area west of Route 1. The ARVN and Marines found little sign of any major VC force in the area and encountered only scattered resistance.[4]: 69

Eight days after Thunderbolt, the Allies finally confirmed the location of the 1st VC Regiment. On 15 August, a deserter from the regiment surrendered to the ARVN. During his interrogation at General Thi's headquarters he revealed that the regiment had established its base in the Van Tuong village complex on the coast, 12 miles (19 km) south of Chu Lai and planned to attack Chu Lai. The prisoner told his interrogators that the 1st VC Regiment at Van Tuong consisted of two of its three battalions, the 60th and 80th, reinforced by the 52nd Company and a company from the 45th Weapons Battalion; approximately 1,500 men in all. Thi, who personally questioned the prisoner and believed the man was telling the truth, relayed the information to Walt. At about the same time, the III MAF intelligence section received corroborative information from another source. Convinced of the danger to the airfield, Walt's subordinates advised a spoiling attack in the Van Tuong region. Walt flew to Chu Lai and held a hurried council of war with his senior commanders there: Brigadier general Frederick J. Karch, who had become the Chu Lai Coordinator on 5 August, Colonel McClanahan of the 4th Marines and Colonel Oscar F. Peatross, the newly arrived 7th Marines' commander. Walt then decided to proceed with an operation.[4]: 70

Planning

In a hectic two-day period, the III MAF, division, wing and 7th Marines staffs assembled forces and prepared plans for the attack. The concept for the operation dictated a two-battalion assault, one battalion to land across the beach and the other to land by helicopter further inland. The division reassigned two battalions previously under the operational control of the 4th Marines to Peatross as the assault battalions, Lieutenant Colonel Joseph R. Fisher's 2nd Battalion, 4th Marines and Lieutenant Colonel Joseph E. Muir's 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marines. Walt, who wanted a third battalion as a floating reserve, requested permission to use the Shore Landing Force (SLF) which Admiral U. S. Grant Sharp Jr. approved immediately. At the time of the request the amphibious task force was located at Subic Bay Naval Base, 720 miles (1,160 km) away. Based upon its transit time to the operational area, the planners selected 18 August as D-Day. The operation was originally called Satellite, but a power blackout led to a clerk working by candlelight typing "Starlite" instead.[4]: 70

In order to maintain the secrecy of the operation, none of the ARVN Joint General Staff were informed about the operation until after it had started. Only Generals Thi and ARVN 2nd Division commander General Hoàng Xuân Lãm had advance knowledge of the operation in order to keep ARVN forces out of the operational area.[4]: 82–3

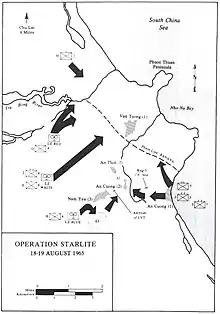

Peatross and his commanders conducted an aerial surveillance of the area and selected the amphibious assault landing site, as well as the helicopter landing zones (LZs). They chose the beach north of the coastal hamlet of An Cuong, later designated Green Beach, for the landing. A force there would block VC avenues of escape to the south. Three LZs, Red, White and Blue, were selected 4 miles (6.4 km) east of Route 1 and roughly 1 mile (1.6 km) inland from the coast. LZ Blue, about 2 km west of Green Beach, was the southernmost of the LZs. White was 2 km west northwest of Blue, while Red was 2 km north of White. From these positions, the Marines were to move northeast to the South China Sea.[4]: 71

On the morning of the 17th the plans were completed. 3/3 Marines was to land across Green Beach at 06:30, 18 August with Companies I and K abreast, K on the right. Company L, the battalion reserve, was to follow as the lead companies swerved to the northwest. The remaining company, Company M, was to make an overland movement from Chu Lai to a ridgeline blocking position in the northern portion of the operations area, 4 miles (6.4 km) northwest of Green Beach and 1 mile (1.6 km) inland from the sea, closing off the VCs' retreat. Soon after H-Hour, UH-34s from HMM-261 and HMM-361 were to shuttle the 2/4th Marines into the three LZs. The two battalions were to join forces when Company H from LZ Blue linked up with Company I outside the hamlet of An Cuong , 1.8 km inland from Green Beach. From there, the Marines were to sweep to the sea through the Van Tuong village complex and over the Phuoc Thuan Peninsula. Artillery batteries at Chu Lai were to provide artillery support while two United States Navy destroyers, the USS Orleck and the USS Prichett and the cruiser USS Galveston were available for naval gunfire support. Aircraft from Marine Aircraft Group 11 and Marine Aircraft Group 12 were to fly close support for the operation.[4]: 71–2

Battle

At 10:00 on the 17th, Company M, 3/3 Marines boarded LVTP-5s at Chu Lai and moved along the coast to the Trung Phan Peninsula; then the company marched 4 miles (6.4 km) south where it established its blocking position. The Marines of Company M met only minor resistance, an occasional sniper and booby traps. Before dawn on the 18th, the company reached its objective and dug in. Marine patrols had been active in this area for some time and to the casual observer the company's activity was just another small unit movement. At 17:00 on 17 August, the rest of 3/3rd Marines, with Colonel Peatross and his staff, embarked on the three ships of the amphibious task group, USS Bayfield, USS Cabildo and USS Vernon County. Three M67 Flame Thrower Tanks attached to the 7th Marines and a platoon of five M48 tanks assigned to Fisher's battalion boarded two LCUs, which then sailed independently towards the amphibious objective area, timing their arrival to coincide with that of the troop transports. The task force first sailed east to deceive any VC in sampans in the coastal waters. Once over the horizon, the ships changed course to the southwest, arriving in the amphibious objective area shortly after 05:00. There they were joined by the Galveston and the Orleck, which were to cover the landing.[4]: 72

At 06:15, 15 minutes before H-Hour, Battery K, 4th Battalion, 12th Marines, which had displaced to firing positions on the northern bank of the Trà Bồng River the night before, began 155 mm preparation fires of the helicopter landing zones. The artillery was soon reinforced by 20 Marine A-4s and F-4s which dropped 18 tons of bombs and napalm on the LZs. The Marines limited their preparation of Green Beach to 20mm cannon strafing runs by MAG-12 A-4s, because of the proximity of An Cuong to the landing site. As the air and artillery fires lifted, the ground forces arrived, Companies I and K, in LVTP-5s, landed across Green Beach at 06:30 and pushed inland according to plan. The troops quickly spread out and moved into An Cuong. After a futile search for VC, the company continued advancing to the west. Company K received sniper fire from its right as it crossed the northern portion of Green Beach. Two platoons quickly moved northward and the VC fire ceased. The third platoon secured the northern half of An Cuong. Fifteen minutes after H-Hour, Company G, 2/4th Marines landed at LZ Red. Company F and the command group landed at LZ White and Company H arrived at LZ Blue 45 minutes later. On the beach, Muir, who had moved his command post ashore, was joined at 07:30 by Peatross and his staff. Tanks and M50 Ontos rolled off the LCUs and landing craft mechanized (LCMs) and made their way forward to support the assault companies. Company L came ashore and established perimeter security for the supply area at the beach. Most of the Marine companies met only light resistance as they moved into the attack. Company G searched two hamlets in the vicinity of LZ Red and then advanced to the northeast and linked up with Company M without incident. At LZ White Company E encountered stiffer opposition from the VC. The VC manned firing positions on a ridgeline east and northeast of the LZ, employing mortars, machine guns, and small arms. After dogged fighting, the Marines cleared the hills. By midmorning, Company E began moving northeast. At one juncture, the Marines spotted about 100 VC in the open and asked for artillery fire. The 107mm Mortar (Howtar) Battery, 3rd Battalion, 12th Marines, helilifted into the position held by Company M, shelled the VC force killing an estimated 90 VC. Company E continued to push forward, finding only occasional opposition.[4]: 72–3

Along the coast, Company K had advanced to Phase Line Banana, 2 km north of Green Beach. There a VC force, entrenched on a hill overlooking the Marine positions, blocked the advance of the company. Muir, who had established his forward command post with Company K, ordered Company L forward. By midafternoon, the two Marine companies, aided by supporting arms, captured the high ground and set up night defenses. The major action developed in the south near LZ Blue, at the junction of 2/4th Marines and 3/3rd Marines. This area, roughly one square kilometer, was bound by the hamlets of An Thoi on the north, Nam Yen on the south and An Cuong to the east. It was a patchwork of rice paddies, streams, hedgerows, woods and built-up areas, interspersed by trails leading in all directions. Two small knolls dominated the flat terrain, Hill 43, a few hundred meters southwest of Nam Yen, and Hill 30, 400 meters north of An Cuong. LZ Blue was just south of Nam Yen, between Hill 43 and the hamlet. Company H's LZ was almost on top of the VC 60th Battalion. The VC allowed the first helicopters to touch down with little interference, but then opened fire as the others came in. Three U.S. Army UH-1B gunships from the 7th Airlift Platoon, took the VC on Hill 43 under fire while Company H formed a defensive perimeter around the LZ.[4]: 73–5 The Company H commander, First Lieutenant Homer K. Jenkins, was not yet aware of the size of the VC force. He ordered one platoon to take the hill and the rest of the company to secure Nam Yen, both attacks soon stalled. The platoon attacking Hill 43 was still at the bottom of the hill when Jenkins called back his other two platoons from the outskirts of Nam Yen in order to regroup. He requested air strikes against both the VC hill position and Nam Yen and then renewed the attack, but this time, Jenkins moved all three of his platoons into the assault on the hill. The VC fought tenaciously, but the Marines, reinforced by close air support and tanks, were too strong. One Marine platoon counted six dead VC near a heavy machine gun position and more bodies scattered throughout the brush. Jenkins' men took one prisoner and collected over 40 weapons.[4]: 73–5

The airstrikes called by Jenkins against VC positions at Nam Yen momentarily halted the advance of Company I, 3/3rd Marines at a streambed east of Nam Yen. Bomb fragments slightly wounded two Marines. After the bombing run, Company I moved north along the stream for 500 meters to a point opposite An Cuong. Under fire from An Cuong, An Thoi and Nam Yen, Captain Bruce D. Webb, the company commander, requested permission to attack An Cuong, although it was across the bank in the area of responsibility of the 2/4th Marines. Muir approved the request, after consulting with Peatross. An Cuong was a fortified hamlet, ideally suited to VC combat tactics. The area surrounding the hamlet was heavily wooded with severely restricted fields of fire. The only open areas were the rice paddies and even these were interspersed with hedgerows of hardwood and bamboo thickets. An Cuong itself consisted of 25-30 huts, with fighting holes and camouflaged trench lines connected by a system of interlocking tunnels. As the company cleared the first few huts, a grenade exploded, killing Webb and wounding three other Marines. No sooner had the grenade exploded, than two 60mm mortar rounds fell on the advancing troops, inflicting three more casualties. First Lieutenant Richard M. Purnell, the company executive officer, assumed command and committed the reserve platoon. The company gained the upper hand and the action slackened as the troops secured the hamlet. Making a hurried survey of the battlefield, Purnell counted 50 VC bodies. He then radioed his battalion commander for further instructions. Muir ordered Purnell's company to join Company K, which was heavily engaged at Phase Line Banana, 2 km to the northeast. Company H remained near Nam Yen to clean out all VC opposition there and then planned to link up with Muir's battalion.[4]: 75 While Company I maneuvered through An Cuong Peatross committed one company of his reserve battalion to the battle. Company I, 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines on USS Iwo Jima were landed by HMM-163 helicopters shortly after 09:30.[4]: 77

As Company I was preparing to move from An Cuong, a UH-1E gunship from VMO-2 was shot down by VC small arms fire northeast of the hamlet. Muir ordered Purnell to leave some men behind to protect the helicopter. Purnell ordered two squads and three tanks to stay with the helicopter until the craft was evacuated. As the company departed, its members could see that Jenkins' Company H had left Hill 43 and was advancing on the left flank of Company I. At 11:00 Jenkins led his unit, augmented by five tanks and three Ontos, from the Hill 43 area into the open rice paddy between Nam Yen and An Cuong. Jenkins bypassed Nam Yen as he mistakenly believed that Company I had cleared both hamlets. Suddenly, from positions in Nam Yen and from Hill 30, the VC opened up with small arms and machine gun fire, catching the Marine rearguard in a crossfire. Then mortar shells began bursting upon the lead platoons. Company H was taking fire from all directions, and tracked vehicles, Ontos and tanks, were having trouble with the muck of the paddies. Jenkins drew his armor into a tight circle and deployed his infantry. One squad moved to the northwest of Nam Yen and killed nine VC who were manning a mortar, but were driven off by small arms fire and had to withdraw to the relative security of the tanks. Jenkins saw that his position was untenable, and after radioing for supporting arms, he ordered his force to withdraw to LZ Blue. Artillery hit Nam Yen while F-4s and A-4s attacked Hill 30. About 14:00, the company tried to move back to the LZ. The lead platoon was forced to alter course when medical evacuation helicopters tried to land in the midst of the unit. As it maneuvered off to the flank of Company H, this platoon became separated from Jenkins' main body and was engaged by the VC. At this juncture, the platoon unexpectedly linked up with Purnell's helicopter security detail which had started to move toward its parent company after the downed helicopter had been repaired and flown out. The small force was quickly engaged by a VC unit, but together the two Marine units fought their way to An Cuong. Meanwhile, Jenkins and his other two platoons fought a delaying action and withdrew to LZ Blue, arriving there at 16:30. Fisher directed Jenkins to establish a defensive perimeter and await reinforcements.[4]: 76

The expected reinforcements never arrived; they had been diverted to help a supply column that had been ambushed 400m west of An Cuong. Just before noon, Muir had ordered his executive officer in charge of the 3/3rd Marines rear command group, Major Andrew G. Comer, to dispatch the mobile (LVT) resupply to Company I, which, at the time, was only a "few hundred yards" in front of the command group.[4]: 76 Five LVTP-5s and three flame tanks, the only tactical support available at the time, were briefed on the location of the company and marked the routes they were to follow on their maps. The supply column left the command post (CP) shortly after noon, but got lost between Nam Yen and An Thoi. It had followed a trail that was flanked on one side by a rice paddy and on the other by trees and hedgerows. As the two lead vehicles, a tank and an LVTP, went around a bend in the road, an explosion occurred near the tank, followed by another in the middle of the column. Fire from VC recoilless rifles and a barrage of mortar rounds tore into the column. The vehicles backed off the road and turned their weapons to face the VC. Using all of their weapons the troops held off the closing VC infantry. The rear tank tried to use its flamethrower, but a VC shell had rendered it useless. Throughout the fighting, the convoy was still able to maintain communications with the command post, radioing that the column was surrounded by VC and was about to be overrun. The LVT radio operator kept the microphone button depressed the entire time and pleaded for help. The command post was unable to quiet him sufficiently to gain essential information as to their location. This continued for an extended period, perhaps an hour. Informed of the ambush Muir replied that he was returning Company I to the rear CP and ordered Comer to gather whatever other support they could and to rescue them as rapidly as possible. Peatross, well aware of the vulnerable positions of both Company H and the supply column and fearing that the VC was attempting to drive a salient between the two battalions approved a rescue mission. The plan was to use a rapidly moving tank, LVTP and Ontos column through the previously cleared An Cuong area. Before the planning meeting broke up, one of the flame tanks which had been in the supply column arrived at the CP, the crew chief, a staff sergeant, reported that they had just passed through An Cuong without being fired upon and that he could lead them to the supply column.[4]: 76

Shortly after 13:00, Comer's force moved out. Just after cresting Hill 30, the M-48 tank was hit by recoilless rifle fire and stopped short. The other vehicles immediately jammed together and simultaneously mortar and small arms fire saturated the area. Within a few minutes, the Marines suffered five dead and 17 wounded. The infantry quickly dismounted and the Ontos maneuvered to provide frontal fire and to protect the flanks while artillery fire and air support was called in. With the response of supporting arms, the VC fire diminished and Company I was ordered to resume its advance toward An Cuong leaving a small rear guard on Hill 30 to supervise the evacuation of the casualties. The company entered An Cuong against little resistance, but Comer's command group were caught by intense fire from a wooded area to their right front and forced to take what cover they could in the open rice paddies. At the same time, the Marines came upon the two reinforced squads from Company I which had been left to guard the downed Huey and the platoon from Company H. The two squads from Company I fought their way to Hill 30 where they were evacuated while the Company H platoon remained in the rice paddies.[4]: 77

As the intensity of the battle increased, Peatross ordered a halt to the advance of the units from LZs Red and White and along the coast to prevent the overextension of his lines. Company L, 3/7th Marines arrived at the regimental CP at 17:30 and was placed under the operational control of Muir, who ordered them to reinforce Company I in the search for the supply column. Supported by two tanks, Company L moved out. As they advanced through the open rice paddies east of An Cuong, they came under heavy fire, wounding 14 and killing four. The Marines persevered and the VC broke contact as night fell. The addition of a third Marine company to the area, coupled with the weight of supporting arms fire available, evidently forced the VC 60th Battalion to break contact. The Marines radioed the Galveston and Orleck requesting continuous illumination throughout the evening over the Nam Yen-An Cuong area. As darkness fell, Peatross informed Walt that the VC apparently intended to defend selected positions, while not concentrating their forces. Muir decided that it was too risky to continue searching for the supply column that night, especially after having learned that the column, although immobilized, was no longer in danger. Muir ordered Company L to move to Phase Line Banana and join Companies K and L, and establish a perimeter defense there. He also ordered Company I to return to the regimental CP. For all intents and purposes, the fighting was over for Company I; of its 177 men who had crossed the beach, 14 were dead, including the company commander, and another 53 were wounded, but the company claimed 125 VC killed.[4]: 77–8

During the night of 18 August, Peatross brought the rest of the SLF battalion ashore. Company I, 3/7th Marines arrived at the regimental CP at 18:00, followed shortly by Lieutenant Colonel Charles R. Bodley and his command group. Just after midnight, Company M landed across Green Beach from the USS Talladega. With the arrival of his third battalion, Peatross completed his plans for the next day. The concept of action remained basically the same, squeeze the vice around the VC and drive them toward the sea. As a result of the first day's action against the VC 60th Battalion, he readjusted the battalions' boundaries. At 07:30, Muir's 3/3rd Marines, with Companies K and L abreast and Company L, 3/7th Marines following in reserve, was to attack to the northeast from Phase Line Banana. Simultaneously, Fisher's 2/4th Marines, with Companies E and G, was to drive eastward to the sea, joining 3/3rd Marines. Jenkins' Company H, Comer's group, and Company I were to withdraw to the regimental CP. The remainder of 3/7th Marines was to fill the gap. Companies I and M were to move out of the regimental CP, extract the ambushed supply column, and then move toward An Thoi to establish a blocking position there which would prevent the VC from slipping southward. Company M, 3/3rd Marines was to hold its blocking positions further north. The VC were to be left no avenue of escape.[4]: 78–9

On the 19th, 3/7th Marines moved into its zone of action which included the area of the fiercest fighting of the day before, but the VC were gone. At 09:00, Companies I and M left the regimental CP, and moved through An Cuong, meeting no VC resistance. They brought out the supply column and by 15:00 had established their assigned blocking position at An Thoi. Although much of the VC resistance had disappeared, Fisher and Muir still found pockets of stiff opposition when they launched their combined attacks at 07:30. The terrain was very difficult as the rice paddies, ringed by dikes and hedgerows, hindered control, observation and maneuverability. The VC were holed up in bunkers, trenches, and caves which were scattered throughout the area. Marines would sweep through an area, only to have VC snipers fire upon them from the rear. In many cases, the Marines had to dig out the VC or blow up the tunnels. By 10:30, Company E had linked up with Company K and the two battalions continued their advance to the sea. By nightfall, the 2/4th Marines had completed its sweep of the Phuoc Thuan Peninsula. VC organized resistance had ceased.[4]: 79

Aftermath

Although the cordon phase of Starlite had been completed, Walt decided to continue the operation for five more days so that the entire area could be searched systematically. He believed that some of the VC had remained behind in underground hiding places. 2/4th Marines and 3/3rd Marines returned to Chu Lai on the 20th and 1st Battalion, 7th Marines moved into the objective area and joined 3/7th Marines and units from the ARVN 2nd Division for the search. The Marines killed 54 more VC in the Van Tuong complex before Starlite came to an end on 24 August. The Marines had killed 614 VC by body count, taken nine prisoners, held 42 suspects and collected 109 assorted weapons, at a cost of 45 Marines dead and 203 wounded.[4]: 79–80

Corporal Robert E. O'Malley (3/3 Marines) and Lance Corporal Joe C. Paul (2/4 Marines) received the Medal of Honor for their actions during the operation; Muir was awarded the Navy Cross for his actions during the operation. Purnell (3/3 Marines) received the Silver Star for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action.[5] To the Americans, the battle was considered a great success for U.S. forces as they had engaged a local force VC unit and come out victorious. The VC also claimed victory, announcing that they had inflicted 900 American casualties (killed and wounded), destroyed 22 tanks and APCs and downed 13 helicopters, while suffering 200-300 casualties before withdrawing.[6][7]

The ambush of the Marine supply column was reported by journalist Peter Arnett and proved an embarrassment to the Johnson administration, who wanted to retain the secrecy of the operation.[8] The story of the ambush of the Marine supply column was denied by the USMC.[8]

Lessons learned from the battle included the knowledge that the daily allotment of 2 US gallons (7.6 L; 1.7 imp gal) of water per man was inadequate in the heat of Vietnam.[4]: 82

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Marine Corps.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Marine Corps.

- Wilkins, Warren (2011). Grab Their Belts To Fight Them: The Viet Cong's Big-Unit War Against the U.S., 1965–1966. Naval Institute Press. p. 76. ISBN 9781591149613.

- "TRẬN ĐÁNH VẠN TƯỜNG" [The Battle of Wanxiang / The Battle of the Thousand Walls] (in Vietnamese). quangngai.gov.vn. August 17, 2004. Archived from the original on March 2, 2009.

- Hastings, Max (2018). Vietnam: An Epic Tragedy, 1945-1975. Harper. ISBN 9780062405661.

- Shulimson, Jack (1978). U.S. Marines in Vietnam: The Landing and the Buildup 1965 (PDF). History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. ISBN 978-1494287559.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Richard Purnell, , "Military Times", August 18, 1965

- Nguyen Ngoc Toan, "Van Tuong victory raises confidence in defeating US troops", People's Army Newspaper, 21 December 2014.

- Military History Institute of Vietnam (2002). Victory in Vietnam: A History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1954–1975. trans. Pribbenow, Merle. University of Kansas Press. p. 158. ISBN 0-7006-1175-4.

- "The Death of Supply Column 21". Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved 2018-06-13.

Further reading

- Andrew, Rod (2015). The First Fight: U.S. Marines in Operation Starlite, August 1965 (PDF). Marine Corps University, History Division. ISBN 978-0160928796.

- Lehrack, Otto (2004). The First Battle - Operation Starlite and the Beginning of the Blood Debt in Vietnam. Casemate. ISBN 1-932033-27-0.

- Simmons, Edwin H. (2003). The United States Marines: A History, Fourth Edition. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-790-5.

- Summers, Harry G. Historical Atlas of the Vietnam War. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company.