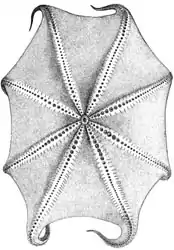

Opisthoteuthis agassizii

Opisthoteuthis agassizii, known as the Agassiz's flapjack octopus,[5] is a lesser-known, deep-sea octopus first described in 1883 by Addison E. Verrill.[6]

| Opisthoteuthis agassizii | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Specimen photographed on a NOAA expedition off the southeastern USA, 2019.[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Cephalopoda |

| Order: | Octopoda |

| Family: | Opisthoteuthidae |

| Genus: | Opisthoteuthis |

| Species: | O. agassizii |

| Binomial name | |

| Opisthoteuthis agassizii | |

Like all cirrate octopuses, O. agassizii has fleshy fins to aid in swimming and a small internal shell. Males are up to four times heavier than females,[7] and their suckers are proportionally larger. Both sexes are small.

This species is found in the north-west, and western Atlantic coasts, over depths of 277 to 1,935 meters (historic records from east Atlantic coasts were likely misidentifications with other Opisthoteuthis).[6][8] Like other opisthoteuthids, they occupy the benthic zone, living on or near the seafloor.[2]

These octopuses most likely prey on polychaete worms and crustaceans that live on or just above the seafloor.[9]

All females of O. agassizii become sexually mature when they reach approximately 190 grams (6.7 ounces) and all males are sexually mature once they reach approximately 95 g (3.4 oz). However, both sexes continue to grow after they reach maturity.

While O. agassizii exists across a wide depth range, heavier octopuses generally live 700 meters or more from the ocean's surface. As age and sexual maturity correlate with weight in this species, this means octopuses at a greater depth are more likely to be sexually mature.[7]

Anatomy and physiology

Size

Opisthoteuthis agassizzi octopuses are small compared to most octopuses; males weigh up to four times more than females, and have a mantle length from 1 up to 2+1⁄2 inches. Males suckers are also much larger. The largest specimen, a male, had a mantle (the body not including the octopus' arms) reaching 63 mm, a little under two and a half inches. The largest mantle length for a female was recorded at 56mm.[6] Body size correlates with age and sexual maturity, so octopuses found at 700 meters or more from the surface are almost always sexually mature.[7]

External and internal characteristics

Fins curl around the mantle of the octopus and aid in swimming and balance, supported by cartilage. A study in a sister species, Opisthoteuthis grimaldii, observed them using the fins to maintain a vertical position in the water relative to the mantle and sea floor.[10] They have eight arms lined with a single line of suckers. Like other octopuses, they use their arms to move about, and their suckers aid in gripping rocks or other objects along their path. Most specimens have been observed having 58-80 suckers per arm.[11] O. agassizii do not have mechanoreceptors lining their suckers like non-cirrate octopuses, nor do they have cilia; instead there are microvilli structures that appear to be used for olfaction. There are two eyes visible within the mantle, but the optic system is much reduced compared to other species within the order Otcopoda.[9] They have a very small shell, like most octopuses do, and have cirri along the undersides of their tentacles.

Lifecycle

Opisthoteuthis agassizii exhibit extended spawning, and the number of egg cells in a female does not appear to correlate with body mass like in most octopus species. One study found that the total weight of a female didn't correlate with the number of oocytes in her body, implying that females continue to produce and lose eggs over the course of their lives. In other words, an octopus of this species might breed multiple times in its life. This is markedly different from most octopuses; the majority only reproduce once in a lifetime.[7] The species appears to continue to grow well after reaching the age of reproduction; one study found that males weighing anywhere from 95 to 5400g were sexually mature, while females from weights of 190g onward to 1650g were sexually mature, further indicating that O. agasizzi has a reproductive cycle differing from that of other octopus species. The exact details on egg development and their reproductive cycle, however, is largely unknown; indeed, only a few octopus species have been studied extensively with regards to reproduction and mating.

Opisthoteuthis agassizii are free-swimming, and spend much of their life just above and on the seafloor (usually below 700 meters).[9] Their weight corresponds with how deep in the ocean they live, however, with some found at depths as shallow as 227 meters.[2] Most are found at much lower depths, up to 1,935 meters below sea level, hence their classification as a deep-sea octopus.[6]

Distribution

Opisthoteuthis agassizii has historically been recorded from both the eastern and western sides of the Atlantic, including along the coasts of the Caribbean, south of Ireland down to the Mediterranean,[9][12] as well as the Gulf of Guinea, Namibia and most of the rest of the West African coast.[13]

However, a revision of the Atlantic Opisthoteuthis published in 2002,[8] indicated that O. agassizii is restricted to the western Atlantic, occurring from the east coast of the US and down as far south as Brazil. The species occurs over depths ranging from 227 to 1935 m. Records from the eastern Atlantic (Mediterranean, Ireland, Western Africa etc.) were likely misidentifications with species O. calypso, O. massyae, and O. grimaldii.[8]

Behavior and ecology

Feeding

Opisthoteuthis agassizii are predacious and tend to eat benthic prey, such as amphipods and polychaetes, but their diet frequently expands to include copepods, decapods, crustaceans, and even microbivalves and microgastropods. There is a slight shift in primary prey as they grow in size; a study found that O. agassizzi under 500g fed mainly on amphipods, while those above 500g ate more polychaetes.[9] They will hunt at any time of day, and most of their preferred prey is slow-swimming. As they are a cirrate octopod, they do not possess a radula, and thus consume prey whole.[11]

Movement

Most of their time is spent along the seafloor, hunting prey and crawling using their eight arms, but O. agassizii can swim like all octopuses are capable of doing. They use their two fins along the mantle for stabilizing themselves, having control over direction, and staying oriented in the water. A study on a related species also showed similar fins being used to aid in buoyancy and ballooning, a common defense mechanism in octopoda.[10] Cirrate octopods cannot, however, swim via jet propulsion, and thus O. agassizii specimens use their fins to drift or pump their arms in contractions to move in a more controlled fashion.[14]

Etymology and phylogeny

Opisthoteuthis agassizii was first named by Verrill in 1883 as just Opisthoteuthis,[15] though the name was soon changed to the now-accepted Opisthoteuthis agassizii. Some work has been done on organizing the Cirrates, but the group is very understudied and only a few theories have been proposed as to their organization into any sort of phylogenetic tree. The most extensive work has been done by Piertney, who used ribosomal DNA sequencing to place the Opisthoteuthidae as a sister family of Grimpoteuthis, Luteuthis, and Cryptoteuthis.[16]

References

- "Dive 12: "Berg Bits"". Ocean Exploration and Research. NOAA. November 19, 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Lyons, G.; Allcock, L. (2014). "Opisthoteuthis agassizii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T163377A1003617. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-3.RLTS.T163377A1003617.en. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- "Species details". Catalogue of Life. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- "Opisthoteuthis agassizii". Ocean Biogeographic Information System. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- "Agassiz's Flapjack Octopus (Opisthoteuthis agassizii)". iNaturalist NZ. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- Vecchione, Michael; Villanueva, Roger; Richard, Young E. "Opisthoteuthis agassizii". Tree of Life Web Project. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Villanueva, Roger (May 19, 1992). "Continuous spawning in the cirrate octopods Opisthoteuthis agassizii and O. vossi: features of sexual maturation defining a reproductive strategy in cephalopods". Marine Biology. Barcelona, Spain. 114 (2): 265–275. doi:10.1007/BF00349529. S2CID 85085295.

- Villanueva, Roger; Collins, Martin; Sánchez, Pilar; Voss, Nancy (2002). "Systematics, distribution and biology of the cirrate octopods of the genus Opisthoteuthis (Mollusca, Cephalopoda) in the Atlantic Ocean, with description of two new species". Bulletin of Marine Science. 71 (2): 933–985.

- Villanueva, Roger; Guerra, Angel (September 1991). "Food and Prey Detection in Two Deep-Sea Cephalopods: Opisthoteuthis Agassizi and O. Vossi (Octopoda: Cirrata)". Bulletin of Marine Science. University of Miami - Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science. 49: 288–299.

- Villanueva, Roger (June 2000). "Observations on the behaviour of the cirrate octopod Opisthoteuthis grimaldii (Cephalopoda)". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 80 (3): 555–556. doi:10.1017/s0025315400002307. ISSN 0025-3154. S2CID 85020724.

- "Opisthoteuthis agassizii". tolweb.org. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- Villanueva, Roger (1992). "Deep-sea cephalopods of the north-western Mediterranean: indications of up-slope ontogenetic migration in two bathybenthic species". Journal of Zoology. 227 (2): 267–276. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1992.tb04822.x. ISSN 1469-7998.

- Adam, W. (1962). "Céphalopodes de l'archipel du Cap-Vert, de l'Angola et du Mozambique". Memórias da Junta de Investigações do Ultramar.

- Villanueva, R.; Segonzac, M.; Guerra, A. (1997). "Locomotion modes of deep-sea cirrate octopods (Cephalopoda) based on observations from video recordings on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge". Marine Biology. 129: 113–122. doi:10.1007/S002270050152. S2CID 85848021.

- "WoRMS - World Register of Marine Species - Opisthoteuthis Verrill, 1883". www.marinespecies.org. Retrieved 2020-11-09.

- Piertney, Stuart B.; Hudelot, Cendrine; Hochberg, F. G.; Collins, Martin A. (May 2003). "Phylogenetic relationships among cirrate octopods (Mollusca: Cephalopoda) resolved using mitochondrial 16S ribosomal DNA sequences". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 27 (2): 348–353. doi:10.1016/s1055-7903(02)00420-7. ISSN 1055-7903. PMID 12695097.