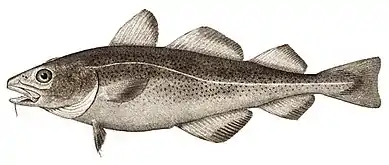

Gilt-head bream

The gilt-head (sea) bream (Sparus aurata) is a fish of the bream family Sparidae found in the Mediterranean Sea and the eastern coastal regions of the North Atlantic Ocean. It commonly reaches about 35 centimetres (1.15 ft) in length, but may reach 70 cm (2.3 ft) and weigh up to about 7.36 kilograms (16.2 lb).[2]

| Gilt-head bream | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Spariformes |

| Family: | Sparidae |

| Genus: | Sparus |

| Species: | S. aurata |

| Binomial name | |

| Sparus aurata | |

| |

The gilt-head bream is generally considered the best tasting of the breams. It is the single species of the genus Sparus – the Latin name for this fish[3] – which has given the whole family of Sparidae its name. Its specific name, aurata, derives from the gold bar marking between its eyes.

The genome of the species was released in 2018, where the authors detected fast evolution of ovary-biased genes likely resulting from the peculiar reproduction mode of the species.[4]

Names

Known as Orata in antiquity and still today in Italy, Malta, and Tunisia (known as "Dorada" in Spain and Romania, "Dourada" in Portugal, "Dorade Royale" in France, "Awrata" in Malta, and "Orada" in Croatia). also known as "Τσιπούρα/chipúra" in greek

Biology

It is typically found at depths of 0–30 metres (0–98 ft), but may occur up to 150 m (490 ft),[2] seen singly or in small groups near seagrass or over sandy bottoms, but sometimes in estuaries during the spring.[2]

It mainly feeds on shellfish, but also some plant material.[2]

Gilt-head bream are protandrous sequential hermaphrodites, maturing as males by age 2, before some develop ovaries and lose their testes in later life.[4]

Fisheries and aquaculture

Gilthead seabream is an esteemed food fish, but catches of wild fish have been relatively modest, between 6,100 and 9,600 metric tons (6,000 and 9,400 long tons; 6,700 and 10,600 short tons) in 2000–2009, primarily from the Mediterranean.[5] In addition, gilthead seabream have traditionally been cultured extensively in coastal lagoons and saltwater ponds. However, intensive rearing systems were developed during the 1980s, and gilthead seabream has become an important aquaculture species, primarily in the Mediterranean area and Portugal. Reported production was negligible until the late 1980s, but reached 140,000 metric tons (140,000 long tons; 150,000 short tons) in 2010, thus dwarfing the capture fisheries production.[6] Turkey is the biggest seabream producer in the world, followed by Greece.[7]

Gilthead seabreams in aquaculture are susceptible to parasitic infections, including from Enterospora nucleophila.[8]

Cuisine

The fish is widely used in Mediterranean cooking, under a variety of names. In Tunisia, it is known locally as "wrata". In Greece, it is known as "tsipoura", in Spain, it is known as "dorada", in Italy, as "orata" and in France, as "dorade".

See also

References

- Russell, B.; Carpenter, K.E.; Pollard, D. (2014). "Sparus aurata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T170253A1302459. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-3.RLTS.T170253A1302459.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2010). "Sparus aurata" in FishBase. October 2010 version.

- sparus. Lewis, Charlton T.; Short, Charles. A Latin Dictionary. Perseus Project.

- Pauletto, Marianna; Manousaki, Tereza; Ferraresso, Serena; Babbucci, Massimiliano; Tsakogiannis, Alexandros; Louro, Bruno; Vitulo, Nicola; Quoc, Viet Ha; Carraro, Roberta (2018-08-17). "Genomic analysis of Sparus aurata reveals the evolutionary dynamics of sex-biased genes in a sequential hermaphrodite fish". Communications Biology. Nature Portfolio. 1 (1): 119. doi:10.1038/s42003-018-0122-7. ISSN 2399-3642. PMC 6123679. PMID 30271999.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) (2011). Yearbook of fishery and aquaculture statistics 2009. Capture production (PDF). Rome: FAO. p. 163. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-05-19.

- "Sparus aurata (Linnaeus, 1758)". Cultured Aquatic Species Information Programme. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- https://www.fao.org/publications/home/fao-flagship-publications/the-state-of-world-fisheries-and-aquaculture/2022/en.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) -

- Han, Bing; Pan, Guoqing; Weiss, Louis M. (2021). "Microsporidiosis in Humans". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. American Society for Microbiology (ASM). 34 (4). doi:10.1128/cmr.00010-20. ISSN 0893-8512. PMC 8404701.

- This review cites this research.

- Palenzuela, Oswaldo; Redondo, María José; Cali, Ann; Takvorian, Peter M.; Alonso-Naveiro, María; Alvarez-Pellitero, Pilar; Sitjà-Bobadilla, Ariadna (2014). "A new intranuclear microsporidium, Enterospora nucleophila n. sp., causing an emaciative syndrome in a piscine host (Sparus aurata), prompts the redescription of the family Enterocytozoonidae". International Journal for Parasitology. Elsevier BV. 44 (3–4): 189–203. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2013.10.005. ISSN 0020-7519. Australian Society for Parasitology.

- Alan Davidson, Mediterranean Seafood, Penguin, 1972. ISBN 0-14-046174-4, pp. 86–108.

External links

Media related to Sparus aurata at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sparus aurata at Wikimedia Commons- Photos of Gilt-head bream on Sealife Collection

.png.webp)