Brodmann area 47

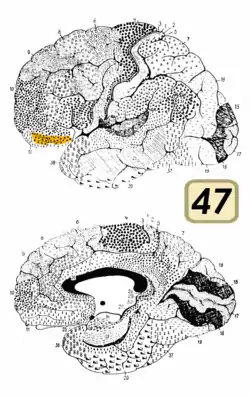

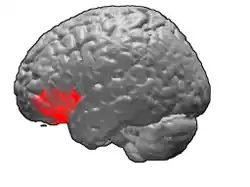

Brodmann area 47, or BA47, is part of the frontal cortex in the human brain. It curves from the lateral surface of the frontal lobe into the ventral (orbital) frontal cortex. It is below areas BA10 and BA45, and beside BA11. This cytoarchitectonic region most closely corresponds to the gyral region the orbital part of inferior frontal gyrus, although these regions are not equivalent. Pars orbitalis is not based on cytoarchitectonic distinctions, and rather is defined according to gross anatomical landmarks. Despite a clear distinction, these two terms are often used liberally in peer-reviewed research journals.

| Brodmann area 47 | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Area orbitalis |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_1779 |

| FMA | 68644 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

BA47 is also known as orbital area 47. In the human, on the orbital surface it surrounds the caudal portion of the orbital sulcus (H) from which it extends laterally into the orbital part of inferior frontal gyrus (H). Cytoarchitectonically it is bounded caudally by the triangular area 45, medially by the prefrontal area 11 of Brodmann-1909, and rostrally by the frontopolar area 10 (Brodmann-1909).

It incorporates the region that Brodmann identified as "Area 12" in the monkey, and therefore, following the suggestion of Michael Petrides, some contemporary neuroscientists refer to the region as "BA47/12".

BA47 has been implicated in the processing of syntax in oral and sign languages, musical syntax, and semantic aspects of language.

Functions and Clinical Considerations

Language Processing and Comprehension

A major function of BA47 is language processing and comprehension. Although Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas are often the major foci of neuroanatomical studies related to language, research has discovered that these two areas are not as integral to language comprehension as originally thought; other structures like BA47 play a major role.[1][2] Specifically, BA47 is active in tasks regarding semantics, or identifying the meaning of words and sentences.[3][4][5] To understand language semantics, consider Dapretto and Bookheimer’s (1999) study where participants needed to identify that there was a difference between the sentences, “The man was attacked by the Doberman,” and “The man was attacked by the Pitbull.” While sentence form was similar, the words Doberman and Pitbull had different meanings, specifically dog breeds.[6] This is indicative of a change in semantics. Having defined what semantics are, it is important to identify the functional limitations of individuals with damage to BA47. Patients with lesions to BA47 reported difficulty engaging in tasks that required one to process words as well as tasks that required one to be familiar with grammatical rules.[7]

Recently, studies have determined that BA47 is involved in processing more than just spoken language. Considering BA47’s role in language semantics, it is essential to note that this function is not related only to oral communication; BA47 is also important for identifying semantics in sign language.[8] Specifically, BA47 plays a role in helping us determine what spoken words mean as well as what signed words mean. This finding that similar areas of the brain are active when processing different types of linguistic information is especially interesting considering the fact that the sensory modalities involved in spoken and sign language are different, the former involves audition and the latter involves vision.[9] Furthermore, in addition to language processing, BA47 helps us process music. Levitin and Menon (2003) found that BA47 showed greater activation when individuals were presented with “scrambled” sounds that violated their expectations versus sounds that went together and confirmed their expectations.[10] That is, with disrupted musical structure, participants required more brain processing for musical comprehension, and that happened in BA47.

Emotional Recognition

BA47 is thought to be related to the recognition of emotions. The emotions thought to be recognized by BA47 are fear, disgust, and anger. In a study conducted by R. Sprengelmeyer, M. Rausch, U.T. Eysel, and H. Pruzentek this hypothesis was tested be using an fMRI experiment on six healthy individuals with no prior neurological problems.[11] The individuals were shown 8 faces showing the emotions of fear, disgust, anger, or neutral. The fMRI image was taken after the subjects were shown the face for 3 seconds. BA47 showed increased activity when the subject was shown the emotions of fear, disgust, and anger.

Animation.

Animation. Frontal view.

Frontal view. Lateral view.

Lateral view.

Further reading

- Ardila, A., Bernal, B., & Rosselli, M. (2017). Should Broca’s area include Brodmann area 47? Psicothema, 29(1), 73-77. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2016.11

- Dapretto, M., & Bookheimer, S. Y. (1999). Form and content: Dissociating syntax and semantics in sentence comprehension. Neuron, 24(2), 427-432. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80855-7

- Dronkers, N. F., Wilkins, D. P., Van Valin, R. D., Redfern, B. B., & Jaeger, J. J. (2004). Lesion analysis of the brain areas involved in language comprehension. Cognition, 92(1-2), 145-177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2003.11.002

- Levitin, DJ; Menon, V (2003). "Musical structure is processed in "language" areas of the brain: A possible role for Brodmann Area 47 in temporal coherence" (PDF). NeuroImage. 20 (4): 242–252. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.08.016. PMID 14683718. S2CID 14691229. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-04-27.

- Molitoris, J., Seay, M., Crinon, J., Newhart, M., Davis, C., & Hillis, A. (2010, May 23–27). The role of Brodmann area 47 in acute stroke Patients with language impairment [Conference session]. Clinical Aphasiology 2010 Conference, Isle of Palms, SC, United States. http://aphasiology.pitt.edu/2162/

- Petrides, M; Pandya, DN (2002). "Comparative cytoarchitectonic analysis of the human and the macaque ventrolateral prefrontal cortex and corticocortical connection patterns in the monkey". European Journal of Neuroscience. 16 (2): 291–310. doi:10.1046/j.1460-9568.2001.02090.x. PMID 12169111. S2CID 40427111.

- Petitto, L. A., Zatorre, R. J., Gauna, K., Nikelski, E. J., Dostie, D., & Evans, A. C. (2000). Speech-like cerebral activity in profoundly deaf people processing signed languages: Implications for the neural basis of human language. PNAS, 97(25), 13961–13966. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.97.25.13961

- Sprengelmeyer, R.; Rausch, M.; Eysel, U. T.; Przuntek, H. (1998). "Neural Structures Associated with Recognition of Facial Expressions of Basic Emotions". Proceedings: Biological Sciences. 265 (1409): 1927–1931. ISSN 0962-8452.

References

- Dronkers, Nina F; Wilkins, David P; Van Valin, Robert D; Redfern, Brenda B; Jaeger, Jeri J (May 2004). "Lesion analysis of the brain areas involved in language comprehension". Cognition. 92 (1–2): 145–177. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2003.11.002. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0012-6912-A. PMID 15037129. S2CID 10919645.

- Ardila, Alfredo; Bernal, Byron; Rosselli, Monica (February 2017). "Should Broca's area include Brodmann area 47?". Psicothema. 29 (1): 73–77. doi:10.7334/psicothema2016.11. PMID 28126062.

- Dapretto, Mirella; Bookheimer, Susan Y (October 1999). "Form and Content". Neuron. 24 (2): 427–432. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80855-7. PMID 10571235. S2CID 18742085.

- Dronkers, Nina F; Wilkins, David P; Van Valin, Robert D; Redfern, Brenda B; Jaeger, Jeri J (May 2004). "Lesion analysis of the brain areas involved in language comprehension". Cognition. 92 (1–2): 145–177. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2003.11.002. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0012-6912-A. PMID 15037129. S2CID 10919645.

- Ardila, Alfredo; Bernal, Byron; Rosselli, Monica (February 2017). "Should Broca's area include Brodmann area 47?". Psicothema. 29 (1): 73–77. doi:10.7334/psicothema2016.11. PMID 28126062.

- Dapretto, Mirella; Bookheimer, Susan Y (October 1999). "Form and Content". Neuron. 24 (2): 427–432. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80855-7. PMID 10571235. S2CID 18742085.

- Dronkers, Nina F; Wilkins, David P; Van Valin, Robert D; Redfern, Brenda B; Jaeger, Jeri J (May 2004). "Lesion analysis of the brain areas involved in language comprehension". Cognition. 92 (1–2): 145–177. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2003.11.002. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0012-6912-A. PMID 15037129. S2CID 10919645.

- Petitto, L. A.; Zatorre, R. J.; Gauna, K.; Nikelski, E. J.; Dostie, D.; Evans, A. C. (2000-12-05). "Speech-like cerebral activity in profoundly deaf people processing signed languages: Implications for the neural basis of human language". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 97 (25): 13961–13966. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.25.13961. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 17683. PMID 11106400.

- Petitto, L. A.; Zatorre, R. J.; Gauna, K.; Nikelski, E. J.; Dostie, D.; Evans, A. C. (2000-12-05). "Speech-like cerebral activity in profoundly deaf people processing signed languages: Implications for the neural basis of human language". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 97 (25): 13961–13966. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.25.13961. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 17683. PMID 11106400.

- Levitin, D (December 2003). "Musical structure is processed in "language" areas of the brain: a possible role for Brodmann Area 47 in temporal coherence". NeuroImage. 20 (4): 2142–2152. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.08.016. PMID 14683718. S2CID 14691229.

- Sprengelmeyer, R.; Rausch, M.; Eysel, U. T.; Przuntek, H. (1998-10-22). "Neural structures associated with recognition of facial expressions of basic emotions". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 265 (1409): 1927–1931. doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0522. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1689486. PMID 9821359.

External links

- For Neuroanatomy of this area visit BrainInfo