Organoiridium chemistry

Organoiridium chemistry is the chemistry of organometallic compounds containing an iridium-carbon chemical bond.[2] Organoiridium compounds are relevant to many important processes including olefin hydrogenation and the industrial synthesis of acetic acid. They are also of great academic interest because of the diversity of the reactions and their relevance to the synthesis of fine chemicals.[3]

_Schematic.png.webp)

12.svg.png.webp)

3O.svg.png.webp)

Classification based on principal oxidation states

Organoiridium compounds share many characteristics with those of rhodium, but less so with cobalt. Iridium can exist in oxidation states of -III to +V, but iridium(I) and iridium(III) are the more common. iridium(I) compounds (d8 configuration) usually occur with square planar or trigonal bipyramidal geometries, whereas iridium(III) compounds (d6 configuration) typically have an octahedral geometry.[3]

Iridium(0)

Iridium(0) complexes are binary carbonyls, the principal member being tetrairidium dodecacarbonyl, Ir4(CO)12. Unlike the related Rh4(CO)12, all CO ligands are terminal in Ir4(CO)12, analogous to the difference between Fe3(CO)12 and Ru3(CO)12.[4]

Iridium(I)

A well known example is Vaska's complex, bis(triphenylphosphine)iridium carbonyl chloride. Although iridium(I) complexes are often useful homogeneous catalysts, Vaska' complex is not. Rather it is iconic in the diversity of its reactions. Other common complexes include Ir2Cl2(cyclooctadiene)2, chlorobis(cyclooctene)iridium dimer, The analogue of Wilkinson's catalyst, IrCl(PPh3)3), undergoes orthometalation:

- IrCl(PPh3)3 → HIrCl(PPh3)2(PPh2C6H4)

This difference between RhCl(PPh3)3 and IrCl(PPh3)3 reflects the generally greater tendency of iridium to undergo oxidative addition. A similar trend is exhibited by RhCl(CO)(PPh3)2 and IrCl(CO)(PPh3)2, only the latter oxidatively adds O2 and H2.[5] The olefin complexes chlorobis(cyclooctene)iridium dimer and cyclooctadiene iridium chloride dimer are often used as sources of "IrCl", exploiting the lability of the alkene ligands or their susceptibility to removal by hydrogenation. Crabtree's catalyst ([Ir(P(C6H11)3)(pyridine)(cyclooctadiene)]PF6) is a versatile homogeneous catalyst for hydrogenation of alkenes.[6]

(η5-Cp)Ir(CO)2 oxidatively adds C-H bonds upon photolytic dissociation of one CO ligand.

Iridium(II)

As is the case for rhodium(II), iridium(II) is rarely encountered. One example is iridocene, IrCp2.[7] As with rhodocene, iridocene dimerises at room temperature.[8]

Iridium(III)

Iridium is usually supplied commercially in the Ir(III) and Ir(IV) oxidation states. Important starting reagents being hydrated iridium trichloride and ammonium hexachloroiridate. These salts are reduced upon treatment with CO, hydrogen, and alkenes. Illustrative is the carbonylation of the trichloride: IrCl3(H2O)x + 3 CO → [Ir(CO)2Cl2]− + CO2 + 2 H+ + Cl− + (x-1) H2O

Many organoiridium(III) compounds are generated from pentamethylcyclopentadienyl iridium dichloride dimer. Many of derivatives feature kinetically inert cyclometalated ligands.[9] Related half-sandwich complexes were central in the development of C-H activation.[10][11]

Organoiridium chemistry has been central to the development of C-H activation, two examples of which are shown here.

Organoiridium chemistry has been central to the development of C-H activation, two examples of which are shown here.

Iridium(V)

Oxidation states greater than III are more common for iridium than rhodium. They typically feature strong-field ligands. One often cited example is oxotrimesityliridium(V).[12]

Uses

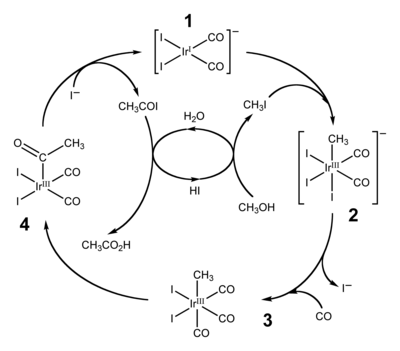

The dominant application of organoiridium complexes is as catalyst in the Cativa process for carbonylation of methanol to produce acetic acid.[13]

Optical devices and photoredox

Iridium complexes such as cyclometallated derived from 2-phenylpyridines are used as phosphorescent organic light-emitting diodes.[14] Related complexes are photoredox catalysts.

Potential applications

Iridium complexes are highly active for hydrogenation both directly and via transfer hydrogenation. The asymmetric versions of these reactions are widely studied.

Many half-sandwich complexes have been investigated as possible anti-cancer drugs. Related complexes are electrocatalysts for the conversion of carbon dioxide to formate.[9][15] In academic laboratories, iridium complexes are widely studied because its complexes promote C-H activation, but such reactions are not employed in any commercial process.

See also

- Category:Iridium compounds

References

- S. M. Bischoff; R. A. Periana (2010). Oxygen and Carbon Bound Acetylacetonato Iridium(III) Complexes. Inorganic Syntheses. Vol. 35. p. 173. doi:10.1002/9780470651568. ISBN 978-0-470-65156-8.

- Synthesis of Organometallic Compounds: A Practical Guide Sanshiro Komiya Ed. S. Komiya, M. Hurano 1997

- Crabtree, Robert H. (2005). The Organometallic Chemistry of the Transition Metals (4th ed.). USA: Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 0-471-66256-9.

- Greenwood, N. N.; Earnshaw, A. (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Oxford:Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 1113–1143, 1294. ISBN 0-7506-3365-4.

- Vaska, Lauri; DiLuzio, J.W. (1961). "Carbonyl and Hydrido-Carbonyl Complexes of Iridium by Reaction with Alcohols. Hydrido Complexes by Reaction with Acid". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 83 (12): 2784–2785. doi:10.1021/ja01473a054.

- Crabtree, Robert H. (1979). "Iridium Compounds in Catalysis". Acc. Chem. Res. 12 (9): 331–337. doi:10.1021/ar50141a005.

- Keller, H. J.; Wawersik, H. (1967). "Spektroskopische Untersuchungen an Komplexverbindungen. VI. EPR-spektren von (C5H5)2Rh und (C5H5)2Ir". J. Organomet. Chem. (in German). 8 (1): 185–188. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)84718-X.

- Fischer, E. O.; Wawersik, H. (1966). "Über Aromatenkomplexe von Metallen. LXXXVIII. Über Monomeres und Dimeres Dicyclopentadienylrhodium und Dicyclopentadienyliridium und Über Ein Neues Verfahren Zur Darstellung Ungeladener Metall-Aromaten-Komplexe". J. Organomet. Chem. (in German). 5 (6): 559–567. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)85160-8.

- Liu, Zhe; Sadler, Peter J. (2014). "Organoiridium Complexes: Anticancer Agents and Catalysts". Accounts of Chemical Research. 47 (4): 1174–1185. doi:10.1021/ar400266c. PMC 3994614. PMID 24555658.

- Andrew H. Janowicz; Robert G. Bergman (1982). "Carbon–hydrogen activation in saturated hydrocarbons: direct observation of M + R−H → M(R)(H)". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 104: 352–354. doi:10.1021/ja00365a091.

- Graham, William A.G. (1982). "Oxidative addition of the carbon–hydrogen bonds of neopentane and cyclohexane to a photochemically generated iridium(I) complex". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 104 (13): 3723–3725. doi:10.1021/ja00377a032.

- Hay-Motherwell, R. S.; Wilkinson, G.; Hussain-Bates, B.; Hursthouse, M. B. (1993). "Synthesis and X-ray Crystal Structure of Oxotrimesityl-Iridium(V)". Polyhedron. 12 (16): 2009–2012. doi:10.1016/S0277-5387(00)81474-6.

- Cheung, Hosea; Tanke, Robin S.; Torrence, G. Paul (2000). "Acetic acid". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley. doi:10.1002/14356007.a01_045. ISBN 3-527-30673-0.

- Jaesang Lee; Hsiao-Fan Chen; Thilini Batagoda; Caleb Coburn; Peter I. Djurovich; Mark E. Thompson; Stephen R. Forrest (2016). "Deep Blue Phosphorescent Organic Light-Emitting Diodes with Very High Brightness and Efficiency". Nature Materials. 15 (1–2): 92–98. Bibcode:2016NatMa..15...92L. doi:10.1038/nmat4446. PMID 26480228.

- Maenaka, Yuta; Suenobu, Tomoyoshi; Fukuzumi, Shunichi (2012). "Catalytic interconversion between hydrogen and formic acid at ambient temperature and Pressure". Energy & Environmental Science. 5 (6): 7360–7367. doi:10.1039/c2ee03315a.