Orlando B. Potter

Orlando Brunson Potter (March 10, 1823 – January 2, 1894) was a businessman and member of the United States House of Representatives from New York City. From 1883 to 1885, he served one term in the U.S. House of Representatives. He is primarily recognized for his work to establish the National Banking Act in the United States.

Orlando Brunson Potter | |

|---|---|

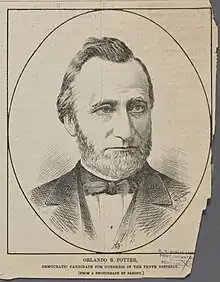

Illustration of Orlando B. Potter from his first run for Congress in 1878 | |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York's 11th district | |

| In office March 4, 1883 – March 3, 1885 | |

| Preceded by | Roswell P. Flower |

| Succeeded by | Truman A. Merriman |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 10, 1823 Charlemont, Massachusetts |

| Died | January 2, 1894 (aged 70) New York City |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Martha Green (Wiley) Potter (1822–1879) |

| Children | Martha Potter (1854–1907) Frederick Potter (1856–1923) Mary Wiley Geer (1857–1931) Ervine Potter (1859–1861) Emma Potter (1860–1867) Blanche Potter (1864–1942) |

| Alma mater | Williams College Harvard Law School |

| Occupation | Businessman, banker, politician |

| Signature | .png.webp) |

Biography

Potter was born March 10, 1823, in Charlemont, Massachusetts, the son of Samuel and Sophia Rice Potter.[1][2] He attended the district school in Charlemont, Williams College, Williamstown, Massachusetts, and the Harvard Law School, Cambridge, Massachusetts, MA (Hon) 1867, LLD 1889. He was admitted to the bar on February 12, 1845, and commenced law practice in Boston, Massachusetts. He married Martha Green Wiley on October 28, 1850. In May 1853, he moved to New York and engaged in manufacturing and patent law as President of the Grover and Baker Sewing Machine Company. And he pursued agricultural interests with a six hundred acre farm on the Hudson in Ossining, New York. He was engaged in commercial real estate development in Manhattan, having developed several commercial buildings in the city. Most notably, he developed the Potter Building in New York City, and later together with Asahel Clarke Geer and his son-in-law Walter Danforth Geer, formed the New York Architectural Terra Cotta Company on Long Island.[3] In 1884, he purchased the site at 71 Broadway and began planning development of the Empire Building, to be later completed by his estate.[4]

He is primarily known for his work to devise the National Banking Act of 1863. In an exhaustive letter to U.S. Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase on August 14, 1861, Potter outlined the means to develop a national banking system. Much of his plan was incorporated into the National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864.[5]

Potter was unsuccessful for election in 1878 to the Forty-sixth Congress. However, he was elected as a Democrat to the Forty-eighth Congress (March 4, 1883 – March 3, 1885) from New York's 11th congressional district. He declined to be a candidate for renomination in 1884 after congressional redistricting was completed that year.

He served as member of the Rapid Transit Commission of New York City 1890-1894 as well as a Cornell University and as a trustee of the New York Savings Bank on Bleecker Street. He died suddenly in New York City, January 2, 1894, and he was thought to have been the wealthiest man in New York City to have died intestate.[3][6] He was interred in Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn along with his wife and three daughters: Mary, Martha, and Blanche.

References

- ERA Nine-generation Database, Edmund Rice (1638) Association, 2012.

- Smith, Elsie Haws. (1954). More About those Rices. Meador Publishers, Boston.

- "Potter Building Landmark Report" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission September 17, 1996. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 19, 2012. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- "Empire Building Landmark Report" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission 25 June 1996. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 12, 2013. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- National Magazine: A Monthly Journal of American History 19:384-393. (November 1893)

- "Orlando B. Potter Left No Will: His many millions go to Mrs. Potter, his son, and three daughters". The New York Times. January 10, 1894. p. 12. Retrieved April 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- United States Congress. "Orlando B. Potter (id: P000466)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.