Osmotic concentration

Osmotic concentration, formerly known as osmolarity,[1] is the measure of solute concentration, defined as the number of osmoles (Osm) of solute per litre (L) of solution (osmol/L or Osm/L). The osmolarity of a solution is usually expressed as Osm/L (pronounced "osmolar"), in the same way that the molarity of a solution is expressed as "M" (pronounced "molar"). Whereas molarity measures the number of moles of solute per unit volume of solution, osmolarity measures the number of osmoles of solute particles per unit volume of solution.[2] This value allows the measurement of the osmotic pressure of a solution and the determination of how the solvent will diffuse across a semipermeable membrane (osmosis) separating two solutions of different osmotic concentration.

Unit

The unit of osmotic concentration is the osmole. This is a non-SI unit of measurement that defines the number of moles of solute that contribute to the osmotic pressure of a solution. A milliosmole (mOsm) is 1/1,000 of an osmole. A microosmole (μOsm) (also spelled micro-osmole) is 1/1,000,000 of an osmole.

Types of solutes

Osmolarity is distinct from molarity because it measures osmoles of solute particles rather than moles of solute. The distinction arises because some compounds can dissociate in solution, whereas others cannot.[2]

Ionic compounds, such as salts, can dissociate in solution into their constituent ions, so there is not a one-to-one relationship between the molarity and the osmolarity of a solution. For example, sodium chloride (NaCl) dissociates into Na+ and Cl− ions. Thus, for every 1 mole of NaCl in solution, there are 2 osmoles of solute particles (i.e., a 1 mol/L NaCl solution is a 2 osmol/L NaCl solution). Both sodium and chloride ions affect the osmotic pressure of the solution.[2]

Another example is magnesium chloride (MgCl2), which dissociates into Mg2+ and 2Cl− ions. For every 1 mole of MgCl2 in the solution, there are 3 osmoles of solute particles.

Nonionic compounds do not dissociate, and form only 1 osmole of solute per 1 mole of solute. For example, a 1 mol/L solution of glucose is 1 osmol/L.[2]

Multiple compounds may contribute to the osmolarity of a solution. For example, a 3 Osm solution might consist of: 3 moles glucose, or 1.5 moles NaCl, or 1 mole glucose + 1 mole NaCl, or 2 moles glucose + 0.5 mole NaCl, or any other such combination.[2]

Definition

The osmolarity of a solution, given in osmoles per liter (osmol/L) is calculated from the following expression:

where

- φ is the osmotic coefficient, which accounts for the degree of non-ideality of the solution. In the simplest case it is the degree of dissociation of the solute. Then, φ is between 0 and 1 where 1 indicates 100% dissociation. However, φ can also be larger than 1 (e.g. for sucrose). For salts, electrostatic effects cause φ to be smaller than 1 even if 100% dissociation occurs (see Debye–Hückel equation);

- n is the number of particles (e.g. ions) into which a molecule dissociates. For example: glucose has n of 1, while NaCl has n of 2;

- C is the molar concentration of the solute;

- the index i represents the identity of a particular solute.

Osmolarity can be measured using an osmometer which measures colligative properties, such as Freezing-point depression, Vapor pressure, or Boiling-point elevation.

Osmolarity vs. tonicity

Osmolarity and tonicity are related but distinct concepts. Thus, the terms ending in -osmotic (isosmotic, hyperosmotic, hyposmotic) are not synonymous with the terms ending in -tonic (isotonic, hypertonic, hypotonic). The terms are related in that they both compare the solute concentrations of two solutions separated by a membrane. The terms are different because osmolarity takes into account the total concentration of penetrating solutes and non-penetrating solutes, whereas tonicity takes into account the total concentration of non-freely penetrating solutes only.[3][2]

Penetrating solutes can diffuse through the cell membrane, causing momentary changes in cell volume as the solutes "pull" water molecules with them. Non-penetrating solutes cannot cross the cell membrane; therefore, the movement of water across the cell membrane (i.e., osmosis) must occur for the solutions to reach equilibrium.

A solution can be both hyperosmotic and isotonic.[2] For example, the intracellular fluid and extracellular can be hyperosmotic, but isotonic – if the total concentration of solutes in one compartment is different from that of the other, but one of the ions can cross the membrane (in other words, a penetrating solute), drawing water with it, thus causing no net change in solution volume.

Plasma osmolarity vs. osmolality

Plasma osmolarity can be calculated from plasma osmolality by the following equation:[4]

where:

- ρsol is the density of the solution in g/ml, which is 1.025 g/ml for blood plasma.[5]

- ca is the (anhydrous) solute concentration in g/ml – not to be confused with the density of dried plasma

According to IUPAC, osmolality is the quotient of the negative natural logarithm of the rational activity of water and the molar mass of water, whereas osmolarity is the product of the osmolality and the mass density of water (also known as osmotic concentration).[1]

In simpler terms, osmolality is an expression of solute osmotic concentration per mass of solvent, whereas osmolarity is per volume of solution (thus the conversion by multiplying with the mass density of solvent in solution (kg solvent/litre solution).

where mi is the molality of component i.

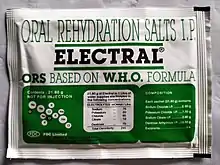

Plasma osmolarity/osmolality is important for keeping proper electrolytic balance in the blood stream. Improper balance can lead to dehydration, alkalosis, acidosis or other life-threatening changes. Antidiuretic hormone (vasopressin) is partly responsible for this process by controlling the amount of water the body retains from the kidney when filtering the blood stream.[6]

References

- D. J. Taylor, N. P. O. Green, G. W. Stout Biological Science

- McNaught, A. D.; Wilkinson, A.; Chalk, S. J. (1997). IUPAC. Compendium of Chemical Terminology (the "Gold Book") (2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications. ISBN 0-9678550-9-8. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- Widmaier, Eric P.; Hershel Raff; Kevin T. Strang (2008). Vander's Human Physiology, 11th Ed. McGraw-Hill. pp. 108–12. ISBN 978-0-07-304962-5.

- Costanzo, Linda S. (2017-03-15). Physiology. Preceded by: Costanzo, Linda S., 1947- (Sixth ed.). Philadelphia, PA. ISBN 9780323511896. OCLC 965761862.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Martin, Alfred N.; Patrick J Sinko (2006). Martin's physical pharmacy and pharmaceutical sciences: physical chemical and biopharmaceutical principles in the pharmaceutical sciences. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. p. 158. ISBN 0-7817-5027-X.

- Shmukler, Michael (2004). Elert, Glenn (ed.). "Density of blood". The Physics Factbook. Retrieved 2022-01-23.

- Earley, L. E.; Sanders, C. A. (1959). "The Effect of Changing Serum Osmolality on the Release of Antidiuretic Hormone in Certain PAtients with Decompensated Cirrhosis of the Liver and Low Serum Osmolality". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 38 (3): 545–550. doi:10.1172/jci103832. PMC 293190. PMID 13641405.