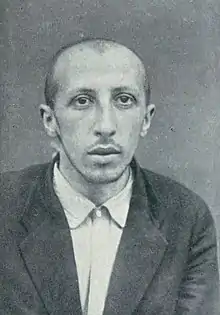

Ottó Korvin

Ottó Korvin (born Ottó Klein, 24 May 1894 in Nagybocskó – 28 December 1919 in Budapest) was a communist politician of Hungary. He also served as the chief of the Political Department of Internal Affairs.[1][2]

After the fall of the Hungarian Soviet Republic, Korvin was arrested by counter-revolutionary forces and hanged.

He was also the brother of József Kelen.[3]

Biography

Born into a wealthy, enlightened Jewish family, his mother was Berta Eisenstädt and his father was Zsigmond Klein, a store manager who settled in Nagybocsk at the end of the 19th century. They had two children: József Klein (later József Kelen) and Otto. Later they moved to Maramures Island, and the children went to school here, and from 1906 they lived in Budapest, where Otto became a member of the Galilee Circle. He was made a poet and took the name Korvin on the advice of an editor. In the early 1910s, he met Zoltán Franyó, art historian Hugó Kenczler, and Tibor Szamuely. In 1912, he published a lyrical portfolio entitled "Sápadások" ( "Pallors" ).

His father, meanwhile, rented a forest in Oszatelep and set up a logging farm, where he called his son, Otto (1912), and he was announced as "forest manager". After the outbreak of World War I, Otto enlisted as a soldier, but was suppressed because of his spine problems. He returned to Oszatelep and continued his work until 1917.

At the beginning of 1917, Korvin arrived in Budapest. Here he studied social sciences and became acquainted with Marxism. As the department head of the capital Fabank bank, he joined the left-wing group of the National Association of Financial Institution Officials and also attended the lectures of Ervin Szabó at the Galilei Circle. On May 1, 1917, he took part in the first workers' demonstration during the war. He was also active in the antimilitarist movement, organizing the Galileans, and then after the arrest of the Galilean leaders in January 1918, he became the illegal antimilitarist movement, the so-called leader of revolutionary socialists. In his pamphlets, he encouraged factory workers to form works councils. He was a part of the For All On March 15, 1918. preparation and distribution of a leaflet. After the victory of the bourgeois democratic revolution in October 1918, he became the leader of a group of antimilitarist Galileans (so-called revolutionary socialists) already operating legally at that time. He participated in the establishment of the Communist Party (KMP) and then became a member of the Central Committee. He left Fabank bank and continued to work as a cashier for the Communist Party. For the Red Newspaper, when they didn’t want to give them paper, he got the paper from the black market. He was arrested on February 20, 1919. In prison on March 21, he typed the text on the merger of the two parties (MSZDP and KMP). In 1919, Klein changed his family name to Corvin.

His role in the Hungarian Soviet Republic

After the proclamation of the Soviet Republic, he first became the head of the commercial department of the Socialist Production Committee and issued a decree on the socialization of shops (meaning: nationalization and confiscation). He was later replaced by Dr. Joseph Wagas. His companion was Imre Sallai, his deputies were Ferenc Stein, János Guzi and Károly Benyovszky. The Budapest Revolutionary Court sentenced many people to death on the instructions of Korvin and Jenő László for a crime of counter-revolutionary behavior. Korvin also organized the defense apparatus of the council state. In mid-May 1919, after disarming the Chernig group, 43 people were assigned under Corvary's command in the Political Investigation Department. At the National Assembly of the Councils (June 23), he was elected a member of the Allied Central Management Committee, which re-elected the People's Commissars the next day, June 24. After the fall of the Soviet Republic, on the second of August, while the other Commissars left the country by train departing from Kelenföld, he worked in the Political Investigation Department with Salsa Stein and Ferenc Stein who tried to destroy all of the documents of their department.

After the fall of the communist regime

He then worked on organizing the illegal communist party, together with György Lukács. His illegal apartment was at 21 Naphegy Street, and he also received a fake passport with the pseudonym Béla Kornis. But that did not help either,as he soon fell into police hands. István Sulyok, whom he met on the day of his arrest, wrote the following about the arrest and torture of Korvin in a prison on Margit Korvin Boulevard: "On August 7, I ventured into Elizabeth Square, where I met Comrade Korvin. , the other caught Comrade Corvin, I jumped under the gate and managed to hide between the trash cans until the gate closed. The next day, to my misfortune, Detective Péter Egri recognized me and took me to the headquarters, where we were already crowded with 2-300 people. At dawn, they shoved a battered, bloody human wreck and called out to me, "Look, here's your boss. You're doing the same, and now kiss me." Team leader Schnell, Comrade Korvin, burned his cigar with a cigar, and then I followed. Ottó Korvin's lawsuit began on December 3, 1919, under M.E. 4039/1919. on the basis of an expedited criminal prosecution procedure regulated by decree, before the advice of Judge Gyula Surgoth. "The crime of Jenő László and his associates" is considered by the Budapest court. Korvin's defense lawyer is dr. It was Sándor Goitein. He wrote his prison diary from 12 December 1919 to 18 December 1919. [8] Although only an assassination attempt against the king could be punished by death under the contemporary penal code, a decree of the Friedrich government overruled this, and on this basis, on 19 December 1919, Corvin and his eight associates were sentenced to death. The death sentence was executed on the morning of December 29, 1919.

References

- Handler, Andrew. Blood Libel at Tiszaeszlar. Boulder. p. 257.

- Éva Fekete; Éva Karádi (1981). György Lukács: His Life in Pictures and Documents. Corvina Kiadó. p. 115.

- Eckelt, Frank (1965). The Rise and Fall of the Béla Kun Regime in 1919. New York University. p. 138.