Ottavio Gaetani

Ottavio Gaetani (22 April 1566 - 8 March 1620) was an Italian Jesuit and historian, writing exclusively in Latin and most notable for his Vitae Sanctorum Siculorum. He is held to be the founder of hagiography in his native Sicily and one of the island's main 16th-century and early 17th-century historians.[1]

Ottavio Gaetani | |

|---|---|

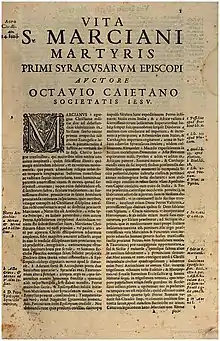

'Life of Santi Marcianus, martyr, first bishop of Syracuse' from Gaetani's Vitae Sanctorum Siculorum | |

| Born | 22 April 1566 Syracuse, Kingdom of Sicily |

| Died | 8 March 1620 Palermo, Kingdom of Sicily |

| Occupation | Historian, Catholic priest |

| Known for | Vitae Sanctorum Siculorum |

| Family | Constantino Cajetan |

Life

Born in Syracuse, he was the son of Barnaba Gaetani and his wife Gerolama Perno, a cadet member of the family of the barons of Sortino and a daughter of the baron of Floridia respectively. He had five brothers - Giulio Cesare and Onorato (both doctors of civil and ecclesiastical law), Domizio (a doctor of theology and canon of Syracuse Cathedral), Alfonso (a fellow Jesuit), Costantino (a Benedictine abbot, director of the Vatican Library, secretary to Pope Pius V and prefect of the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith) - as well as two sisters named Giovanna and Angelica Maria.

He showed a religious disposition in childhood and decided on a life in the church, joining the Society of Jesus on 20 May 1582. His priestly vocation had been confirmed by a vision he had whilst praying in the church of Syracuse's Jesuit College - it showed a large shining flame above the head of the church's crucifix. His decision to become a Jesuit was initially vetoed by his father, but Ottavio won him round and he joined the Jesuit College in Messina to complete the novitiate.

In 1592 he moved to Rome to study at the General Curia, where he met the Order's general Claudio Acquaviva and his secretary Jacques Sirmond, becoming close friends with both of them.[2] After completing his studies and being ordained priest, the Order ordered him back to Sicily in 1597 as 'magistratum' of its College in Messina, but for unknown reasons he instead chose to settle in Palermo, where other brothers of the Order highly esteemed him for his spiritual virtues - sources state he slept on bare boards and heavily scourged himself.

This period includes the origins of his masterwork Vitae Sanctorum Siculorum or to give it is full title Vitae Sanctorum Siculorum ex antiquis Graecis Latinisque Monumentis et ut plurimum ex M.S.S. Codicibus nondum editis collectae, aut scriptae, digeste iuxta seriem annorum Christianae Epochae et Animadversionibus illustratae (Lives of the Sicilian Saints from ancient Greek and Latin Monuments and for the most part from unpublished manuscript codices or writings, sorted by years of the Christian Epoch and explained with observations).[3] This was composed according to a plan originally appearing in his Idea operis de vitis sanctorum Siculorum, whose full title was Idea operis de vitis siculorum sanctorum famave sanctitatis illustrium Deo volente bonis iuvantibus in lucem prodituri (Report of the works and lives of the Sicilian saints whose notable sanctity has been brought to light in good works by God's will). Both works reflected the Catholic Reformation's renewed interest in saints' hagiographies. He was able to gather many rare manuscripts thanks to wide network of correspondents and collaborators, especially his book-loving brother Costantino, who sent many manuscripts from Rome.[4] and Jacques Sirmond. Gaetano also had several translations of vitae (saints' lives), encomiums and hymns made for him by Agostino Fiorito (1580-1613), Jesuit professor of Greek in Palermo, as well as earlier translators such as Sirmond, Luigi Lippomano, Francesco Maurolico, and the Jesuit Francesco Rajato (1578–1636).[5]

He was commissioned by the Senate of Palermo to write a funerary oration on the death of Philip II of Spain in 1598 and to deliver it in the cathedral - it was also published three years later. In 1600, according to legend, a woman several times tried to seduce and kill him, but he was saved by Ignatius of Loyola, to whose cult Gaetani was devoted. In 1603 he was ordered back to the Jesuit College in Messina as its head, though in 1607 he was temporarily transferred to Catania. He was then ordered back to Palermo in 1608, where he remained until his death there twelve years later after a long illness. In 1610 he published De die natali S. Nymphae Virginis ac martyris Panhormitanae (On the birthday of Saint Nympha, virgin and martyr of Palermo), dedicated to the Genoese cardinal Giannettino Doria, Archbishop of Palermo. Another legend holds that in 1611 Gaetani had a miraculous vision of the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child surrounded by angels. In September 1614 he was appointed head of the Casa Professa and after a short time became Preposto of the Collegio del Gesù Grande, quickly improving the financial situation of the College in Palermo, which had fallen heavily into debt.

He was relieved of all duties in 1611 due to illness and replaced as rector of the Casa Professa by father Girolamo Tagliavia. During this time he finally managed to publish Idea operis in 1617, but Vitae Sanctorum Siculorum and Isagoge ad Historiam sacram siculam (Isagoge ad historiam sacram Siculam, ubi tam veteris Siciliae impiae superstitiones, quam verae fidei in eadem insula initia, propagatio et augmenta, Siculorum in religionem Christianam ardor et in ea constantia, aliaque hujus argumenti, eruditione copiosissima, et singulari methodo exponuntor[6] remained incomplete on his death. His notes are mainly held in the Biblioteca centrale della Regione Siciliana in Palermo and the Society of Jesus' own historic archive in Rome.

Works

Vitae Sanctorum Siculorum

The manuscript was edited after its author's death by Pietro Salerno, another Jesuit, and posthumously published in Palermo by Cirilli in 1657.[7][8] The book is still fundamental to Sicilian historical studies, consisting of two folio volumes totalling 825 pages and containing 200 lives, panegyrics, sermons, accounts of relic-translations, hymns and other texts relating to 120 saints, alongside Gaetani's own commentary.[9] Many of the saints' lives edited by Gaetani were later included in the Bollandist Acta Sanctorum[10][11][12][13][14]

Other works

- Octavii Caetani Syracusani e Societate Iesu De die natali S. Nymphae Virginis ac martyris Panhormitanae. Palermo: apud Ioannem Antonium de Franciscis impressorem cameralem. 1610. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- Idea operis de vitis sanctorum Siculorum. Palermo: apud Erasmum Simeonem & socios. 1617. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- Theodosi monachi epistola ad Leonem archidiaconum, de syracusanae expugnatione

- Notae in B. Conradi historiam a Vincentio Littara compendio perscriptam.

Posthumous publications

- Isagoge ad historiam sacram Siculam. Palermo: apud Vincentium Toscanum Coll. Pan. Soc. Jesu typographum. 1707. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- Johann Georg Graevius, Pieter Burman the Elder, ed. (1723). Isagoge ad historiam sacram Siculam (editio novissima auctior et emendatior). Thesaurus Antiquitatum et Historiarum Siciliae. Vol. 2. Leiden: excudit Petrus Vander Aa. pp. 1–234.

References

- Paul Oldfield (2014). Sanctity and Pilgrimage in Medieval Southern Italy, 1000-1200. Cambridge University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-1107000285.

- Giuseppe Rossi Taibbi (1965). Sulla tradizione manoscritta dell'Omiliario di Filagato da Cerami. Quaderni dell'Istituto Siciliano di Studi bizantini e neoellenici (in Italian). Vol. 1–6. p. 14.

- cfr. Benigno e Giarrizzo, op. cit., pp. 2-3.

-

- (in Italian) Rosario Contarino (1960–2020). Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian). Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. ISBN 978-8-81200032-6.

- (in Italian) Maria Stelladoro, Le "Vitae Sanctorum Siculorum" di Ottavio Gaetani: i manoscritti conservati a Palermo e a Roma, Roma 2006 [Supplemento a Studi sull'Oriente Cristiano 10/1].

- cfr. Paul Begheyn, Jesuit Books in the Dutch Republic and its Generality Lands 1567-1773: A Bibliography, BRILL, 2014, p. 291).

- Gaetano, Ottavio (1657). "Volume 1" (in Latin).

- Gaetano, Ottavio (1657). "Volume 2" (in Latin).

- Salvatore Costanza (1983). Per una nuova edizione delle " Vitae sanctorum Siculorum ". « Schede medievali ». p. 313.

- Aprilis, Tom. II, p. 470

- Junii, Tom. II, p. 241

- Julii, Tom. VII, p. 177

- Augusti, Tom. II, p. 174

- (in French) Augustin de Backer (1861). Bibliothèque des écrivains de la compagnie de Jésus. Vol. 7. Liegi: imprimerie de L. Grandmont-Donders, libraire. pp. 164–166.

Bibliography

- (in Italian) Giuseppe Emanuele Ortolani (1818). Biografia degli uomini illustri della Sicilia ornata de' loro rispettivi ritratti. Vol. 2. Naples: Nicola Gervasi.

- (in French) Recensione dell'Isagoge ad historiam sacram siculam. Journal des savants. Vol. 43. Amsterdam: Chez les Jansons à Waesberge. 1709. pp. 289–296.

- (in Italian) Recensione dell'Isagoge ad historiam sacram siculam. Acta Eruditorum. Lipsiae: prostant apud Joh. Grossii haeredes, Joh. Frid. Gleditsch & fil. & Frid. Groschuf. Typis Viduae Christiani Goezii. 1710.

- (in Latin) Emmanuele Aguilera, Provinciae siculae Societatis Jesu, Palermo 1740.

- (in Italian) Giuseppe Maria Mira, Bibliografia siciliana, Palermo 1875-81.

- (in Italian) Antonio Mongitore, Biblioteca sicula, Palermo 1714.

- (in French) Carlos Sommervogel, Bibliothèque de la Compagnie de Jésus, Bruxelles 1890.

- (in Italian) Sara Cabibbo, Il Paradiso del Magnifico Regno, Roma 1996.

- (in Italian) Francesco Benigno and Giuseppe Giarrizzo, Storia della Sicilia, vol. 2, ed. Laterza, Roma-Bari, 1999, ISBN 88-421-0534-1.

- (in Italian) Maria Stelladoro (2004). Gennaro Luongo (ed.). Contributo allo studio delle Vitae Sanctorum Siculorum di Ottavio Gaetani: inventario delle carte preparatorie. Erudizione e devozione. Roma: Viella. pp. 221–312.

External links

- (in Italian) Maria Stelladoro. "L'opera storico-agiografica del gesuita Ottavio Gaetani (1566-1620) nel quadro storico del suo tempo". Retrieved 7 July 2019.