Our Young Folks

Our Young Folks: An Illustrated Magazine for Boys and Girls was a monthly United States children’s magazine, published between January 1865 and December 1873. It was printed in Boston by Ticknor and Fields from 1865 to 1868, and then by James R. Osgood & Co. from 1869 to 1873.[1] The magazine published works by Lucretia Peabody Hale, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Horatio Alger, Oliver Optic, Louisa May Alcott, Thomas Bailey Aldrich, John Greenleaf Whittier, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow[2] and Frances Matilda Abbott.[3]

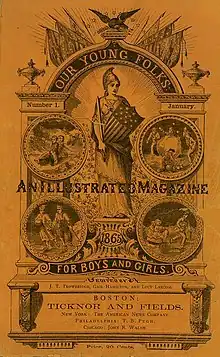

Cover of Our Young Folks magazine (1865) | |

| Editor | Lucy Larcom |

|---|---|

| Categories | Children’s magazine |

| Frequency | Monthly |

| First issue | January 1865 |

| Final issue | December 1873 |

| Country | United States |

In 1874 the periodical merged with St. Nicholas Magazine.

Editors

Lucy Larcom was in charge of the major editorial duties during the magazine’s entire publication history, and she was paid a salary of $1,200 a year. Besides her editorial work Larcom also wrote fiction and non-fiction pieces for Our Young Folks.[4]

John Townsend Trowbridge was also an editor throughout the magazine’s publication run. In addition, he wrote numerous serialized stories for the periodical. Many of his serials, including Jack Hazard and His Fortunes, were later published as books. After the demise of Our Young Folks Trowbridge became a staff writer for St. Nicholas Magazine.[4]

Mary Abigail Dodge, who used the pen name of Gail Hamilton, was editor from 1865 until 1868, when she left after having a disagreement with publisher James T. Fields. In addition to her editorial work she wrote poetry and stories for Our Young Folks.[4]

Content

Our Young Folks was a children's magazine intended for a readership between the ages of ten and eighteen years of age. Each issue had an orange paper cover with a woodcut illustration of Minerva,[4] the Roman goddess of poetry and wisdom. The magazine contained an average of 64 pages of illustrated short stories, articles, poems, songs and serialized stories.[5] The cost was 20 cents per issue, or $2.00 a year.[1]

The publisher described the periodical as "the best juvenile magazine ever published in any land or language" whose editors rejected "dull and trashy articles as alike worthless", taking "all possible care to procure reading that shall furnish entertainment and attractive instructions." Readers were encouraged to pity the poor and exercise appropriate charity. Stories portrayed poverty as being physically hard but morally uplifting.[4] The first of Lucretia Peabody Hale’s The Peterkin Papers stories were published in Our Young Folks.[4] Thomas Bailey Aldrich’s The Story of a Bad Boy was serialized in the periodical.[2] Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote nature articles.[4]

Starting with the first issue the monthly feature Round the Evening Lamp contained charades, arithmetic puzzles and illustrated rebuses.[6] Beginning in January 1866 Our Letter Box shared letters from readers, as well as comments from the editors and writers.[4] Starting in July 1870 Our Young Competitors printed readers' winning entries in writing competitions. This feature was usually four to five pages in length, but some issues had eight pages of readers' writings.[4]

In 1869 the magazine's circulation reached 76,543, but by 1872 the circulation had dropped to 35,000.[1]

Magazine's demise

The final issue of Our Young Folks, dated December 1873, gave no indication that the magazine was about to cease being published. An editorial piece in Our Letter Box announced a new serial for 1874, as well as an “unusually interesting variety of articles by our best writers.” Readers were told that the publisher had promised to send a chromo (colored picture) to every subscriber who sent in the full subscription price for 1874.[7]

Subscribers received the January 1874 issue of St. Nicholas Magazine, which contained A Card from the Editor of Our Young Folks. John Townsend Trowbridge wrote: "Through the courtesy of the conductor of ST. NICHOLAS, I am enabled to say a few words to the readers of ‘Our Young Folks,’ in place of the many I should have wished to say in the last number of that lamented magazine, had it been known to be the last when it left the editorial hands. That number was sent to its readers in the full faith that all it promised them for the coming year was to be more that fulfilled. But it had scarcely gone forth, when came the sudden change by which ‘Our Young Folks’ ceased to exist – the result of a purely commercial transaction, wholly justifiable, I think, on the part of the publishers, J. R. Osgood and Company, of whose honorable and liberal conduct in all that related to the little magazine, up to the very last, I can speak with the better grace now that my editorial connection with their house has ceased."[1]

In 1874, eight months after the periodical's last issue had been published, a poll taken amongst readers of The Literary World ranked Our Young Folks to be "the best of modern American juvenile magazines".[1]

References

- Pflieer, Pat, American Children's Periodicals, 1789-1872 (Kindle Edition), Merrycoz Books, 2016

- Mott, Frank Luther, A History of American Magazines, Volume III: 1865-1885, Harvard University Press, 1938

- Henry Harrison Metcalf, New Hampshire Women: A Collection of Portraits and Biographical Sketches of Daughters and Residents of the Granite State, page 177, Harvard University, 1895

- Kelly, R. Gordon, Children’s Periodicals of the United States, pages 329 - 341, Greenwood Press, 1984

- Our Young Folks, January – December 1865, December 1873

- Our Young Folks, January 1865

- Our Young Folks, December 1873