Oxford Electric Bell

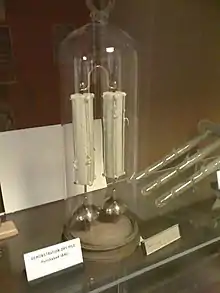

The Oxford Electric Bell or Clarendon Dry Pile is an experimental electric bell, in particular a type of bell that uses the electrostatic clock principle that was set up in 1840 and which has run nearly continuously ever since. It was one of the first pieces purchased for a collection of apparatus by clergyman and physicist Robert Walker.[1][2] It is located in a corridor adjacent to the foyer of the Clarendon Laboratory at the University of Oxford, England, and is still ringing, albeit inaudibly due to being behind two layers of glass.

Design

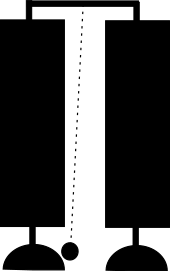

The experiment consists of two brass bells, each positioned beneath a dry pile (a form of battery), the pair of piles connected in series, giving the bells opposite electric charges. The clapper is a metal sphere approximately 4 mm (3⁄16 in) in diameter suspended between the piles, which rings the bells alternately due to electrostatic force. When the clapper touches one bell, it is charged by that pile. It is then repelled from that bell due to having the same charge and attracted to the other bell, which has the opposite charge. The clapper then touches the other bell and the process reverses, leading to oscillation. The use of electrostatic forces means that while high voltage is required to create motion, only a tiny amount of charge is carried from one bell to the other. As a result, the batteries drain very slowly, which is why the piles have been able to last since the apparatus was set up in 1840. Its oscillation frequency is 2 hertz.[3]

The exact composition of the dry piles is unknown, but it is known that they have been coated with molten sulfur for insulation and it is thought that they may be Zamboni piles.[2]

At one point this sort of device played an important role in distinguishing between two different theories of electrical action: the theory of contact tension (an obsolete scientific theory based on then-prevailing electrostatic principles) and the theory of chemical action.[4]

The Oxford Electric Bell does not demonstrate perpetual motion. The bell will eventually stop when the dry piles have distributed their charges equally if the clapper does not wear out first.[5][6] The Bell has produced approximately 10 billion rings since 1840 and holds the Guinness World Record as "the world's most durable battery [delivering] ceaseless tintinnabulation".[2]

Operation

Apart from occasional short interruptions caused by high humidity, the bell has rung continuously since 1840.[7] The bell may have been constructed in 1825.[2]

See also

References

- "Walker, Robert". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/38098. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Exhibit 1 – The Clarendon Dry Pile". Department of Physics. Oxford University. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- Oxford Electric Bell, Atlas Obscura.

- Willem Hackmann. "The Enigma of Volta's "Contact Tension" and the Development of the "Dry Pile"" (PDF). ppp.unipv.it. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- The World's Longest Experiment Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Longest List of the Longest Stuff at the Longest Domain Name at Long Last.

- The Latest on Long-Running Experiments Archived 5 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Improbable Research.

- Ord-Hume, Arthur W. J. G. (1977). Perpetual Motion: The History of an Obsession. George Allen & Unwin. p. 172.

Further reading

- Willem Hackmann, "The Enigma of Volta's "Contact Tension" and the Development of the "Dry Pile"", appearing in Nuova Voltiana: Studies on Volta and His Times, nb Volume 3 (Fabio Bevilacqua; Lucio Frenonese (Editors)), 2000, pp. 103–119.

- "Exhibit 1 - The Clarendon Dry Pile". Oxford Physics Teaching, History Archive. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- Croft, A J (1984). "The Oxford electric bell". European Journal of Physics. 5 (4): 193–194. Bibcode:1984EJPh....5..193C. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/5/4/001.

- Croft, A J (1985). "The Oxford electric bell". European Journal of Physics. 6 (2): 128. Bibcode:1985EJPh....6..128C. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/6/2/511.

External links

- Oxford Electric Bell, Youtube video with David Glover-Aoki (18 October 2011)