P fimbriae

P fimbriae (also known as pyelonephritis-associated pili) or P pili or Pap are chaperone-usher type (specifically of the π family)[1] fimbrial appendages found on the surface of many Escherichia coli bacteria.[2] The P fimbriae is considered to be one of the most important virulence factor in uropathogenic E. coli and plays an important role in upper urinary tract infections.[3] P fimbriae mediate adherence to host cells, a key event in the pathogenesis of urinary tract infections.

Structure and expression

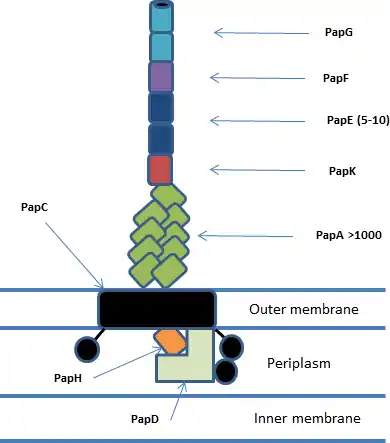

P fimbriae are large, linear structures projecting from the surface of the bacterial cell. With lengths of 1-2um, the pili can be larger than the diameter of the bacteria itself.[4] The main body of the fimbriae is composed of approx. 1000 copies of the major fimbrial subunit protein PapA, forming a helical rod.[5] The short fimbrial tip is made of the subunits PapK, PapE, PapF and the tip adhesin PapG, which mediates the binding.

The fimbriae is assembled by a chaperone-usher system, and proteins required for the assembly are expressed by the Pap operon, which is located on pathogenicity islands. The genes of the Pap operon encode five structural proteins (PapA, PapK, PapE, PapF and PapG), four proteins involved in the transport and assembly (PapD, PapH, PapC, PapJ) and two proteins (PapB, PapI) regulating the operon expression.[6][7]

Role during infection

Adherence to host uroepithelial cells is a crucial step during the infection that allows uropathogenic E.coli to colonize the urinary tract and prevents bacterial removal during micturition. The binding of the P fimbriae to epithelial cells is mediated by the tip adhesin PapG. Four different alleles of PapG have been described, which bind to different glycolipid structures on host cells. In humans, especially variant papGII and papGIII have shown to be clinically relevant.

Variant PapGII binds preferentially to globoside (GbO4), found abundantly on human kidney epithelial cells. PapGII triggers a strong inflammatory response which leads to tissue damage.[8] Most E. coli strains causing pyelonephritis, urinary-source bacteremia and urosepsis produce P pili with PapGII.[9] PapGIII binds to the Forssmann antigen (GbO5) as well as isoreceptors present in the urinary tract of humans. E. coli strains carrying the papGIII gene are associated with lower urinary tract infections (cystitis) and asymptomatic bacteriuria. PapGI adhesins bind preferentially to globotriaosylceramide (GbO3), while the isoreceptors of PapGIV are unknown. E. coli carrying genes for PapGI and PapGIV are rarely found in E. coli causing infections in humans.[3][4]

| fecal | asymptomatic bacteriuria | cystitis | pyelonephritis | urosepsis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| papGII | 15 | 20 | 20 | 60 | 70 |

| papGIII | 10 | 15 | 20 | 20 | 10 |

References

- Nuccio SP, et al. (2007). "Evolution of the chaperone/usher assembly pathway: fimbrial classification goes Greek". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 71 (4): 551–575. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00014-07. PMC 2168650. PMID 18063717.

- Rice JC, Peng T, Spence JS, Wang HQ, Goldblum RM, Corthésy B, Nowicki BJ (December 2005). "Pyelonephritic Escherichia coli expressing P fimbriae decrease immune response of the mouse kidney". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 16 (12): 3583–91. doi:10.1681/ASN.2005030243. PMID 16236807.

- Lane MC, Mobley HL (July 2007). "Role of P-fimbrial-mediated adherence in pyelonephritis and persistence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) in the mammalian kidney". Kidney International. 72 (1): 19–25. doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5002230. PMID 17396114.

- Wullt B, Bergsten G, Samuelsson M, Svanborg C (June 2002). "The role of P fimbriae for Escherichia coli establishment and mucosal inflammation in the human urinary tract". International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 19 (6): 522–38. doi:10.1016/S0924-8579(02)00103-6. PMID 12135844.

- Hospenthal MK, Redzej A, Dodson K, Ukleja M, Frenz B, Rodrigues C, et al. (January 2016). "Structure of a Chaperone-Usher Pilus Reveals the Molecular Basis of Rod Uncoiling". Cell. 164 (1–2): 269–278. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.049. PMC 4715182. PMID 26724865.

- Waksman G, Hultgren SJ (November 2009). "Structural biology of the chaperone-usher pathway of pilus biogenesis". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 7 (11): 765–74. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2220. PMC 3790644. PMID 19820722.

- Lillington J, Geibel S, Waksman G (September 2014). "Biogenesis and adhesion of type 1 and P pili". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 1840 (9): 2783–93. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.04.021. PMID 24797039.

- Ambite I, Butler DS, Stork C, Grönberg-Hernández J, Köves B, Zdziarski J, et al. (June 2019). "Fimbriae reprogram host gene expression - Divergent effects of P and type 1 fimbriae". PLOS Pathogens. 15 (6): e1007671. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1007671. PMC 6557620. PMID 31181116.

- Biggel M, Xavier BB, Johnson JR, Nielsen KL, Frimodt-Møller N, Matheeussen V, et al. (November 2020). "Horizontally acquired papGII-containing pathogenicity islands underlie the emergence of invasive uropathogenic Escherichia coli lineages". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5968. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5968B. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19714-9. PMC 7686366. PMID 33235212. S2CID 227167609.

- Johnson JR (September 1998). "papG alleles among Escherichia coli strains causing urosepsis: associations with other bacterial characteristics and host compromise". Infection and Immunity. 66 (9): 4568–71. doi:10.1128/IAI.66.9.4568-4571.1998. PMC 108561. PMID 9712823.

- Johanson IM, Plos K, Marklund BI, Svanborg C (August 1993). "Pap, papG and prsG DNA sequences in Escherichia coli from the fecal flora and the urinary tract". Microbial Pathogenesis. 15 (2): 121–9. doi:10.1006/mpat.1993.1062. PMID 7902954.

- Johnson JR, Kuskowski MA, Gajewski A, Soto S, Horcajada JP, Jimenez de Anta MT, Vila J (January 2005). "Extended virulence genotypes and phylogenetic background of Escherichia coli isolates from patients with cystitis, pyelonephritis, or prostatitis". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 191 (1): 46–50. doi:10.1086/426450. PMID 15593002.

- Mabbett AN, Ulett GC, Watts RE, Tree JJ, Totsika M, Ong CL, et al. (January 2009). "Virulence properties of asymptomatic bacteriuria Escherichia coli". International Journal of Medical Microbiology. 299 (1): 53–63. doi:10.1016/j.ijmm.2008.06.003. PMID 18706859.

- Marrs CF, Zhang L, Foxman B (November 2005). "Escherichia coli mediated urinary tract infections: are there distinct uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) pathotypes?" (PDF). FEMS Microbiology Letters. 252 (2): 183–90. doi:10.1016/j.femsle.2005.08.028. PMID 16165319.