Pa Tepaeru Terito Ariki

Pa Tepaeru Terito Ariki[1], Lady Davis (14 August 1923 – 3 February 1990) was Pa Ariki, one of the two ariki titles of the Takitumu tribe on the island of Rarotonga of the Cook Islands from 1924 until 1990.

| Pa Tepaeru Terito Ariki, Lady Davis | |

|---|---|

| High Chieftess of Takitumu | |

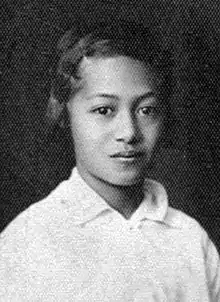

Pa Tepaeru Terito Ariki in 1934 | |

| Reign | 1924–1990 |

| Successor | Marie Peyroux |

| Born | 14 August 1923 |

| Died | 3 February 1990 (aged 66) Auckland, New Zealand |

| Spouse | George Ani Peyroux Tom Davis |

| House | House of Takitumu |

| Dynasty | Pa Dynasty |

She is one of the authors of "Te Atua Mou E" ("God is Truth"), the national anthem of the Cook Islands.[2] She was president of the House of Ariki from 1980 to 1990.

Early life

Pa Tepaeru Terito was an only child, born on 14 August 1923. Her father died four months later. Her mother then remarried.[3] She was raised and educated by her great paternal uncle, Makea'nui Tinirau Teremoana Ariki, head of the Makea Nui Ariki, and his wife Tutini.[3]

She was appointed as Pa Ariki at the age of one in 1924, thanks in part to the support of Tupe Short,[4] an important member of the Kainuku Ariki family, and probably of Makea Nui Tinirau. She was the 47th person to hold the title of Pa Ariki.[5]

In 1934, Pa Terito attended school in New Zealand at the Hukarere Girls' College in Napier. She returned to the Cook Islands in the mid-1940s to assume her role as ariki. She worked as a secretary for the government and later for a private firm.[6]

Conversion to the Baháʼí Faith

In the 1950s, Pa Terito converted to the Baháʼí Faith, becoming the first non-Christian ariki. Her conversion seemed to anger some of the people of Takitumu. According to her, "One of the ministers said to me: 'Pa Ariki, you really have to do something about being a Baha'i. Your people are very angry with you'. (...) My People (held) a meeting (and said): 'Young lady, your ancestors accepted the Gospel' and all this kind of thing and I said: 'Yes, they had their reasons and I've got mine. What you are asking me? Give it up? I would rather give you up. If you ask me to give the title up and leave the country or give up being Baha'i, I'd leave the country.' And they looked at me, because ma'am, they knew I meant it."[7] Her cousin, Makea Nui Tapumanoanoa Teremoana Ariki, also did not approve. "She said to me, 'I do not like you being Baha'i, it's against our family tradition."[7] Pa Terito promised that there would be no attempt to proselytize on her part and agreed to attend the Sunday service at the Cook Islands Christian Church in Ngatangiia.

Family life

Pa Terito married George Tamarua Ani Rima Peyroux in 1946.[8] They had nine children, three sons: Teariki-Upoko-O-Te-Tini-Tini (Sonny), Hironui Maoata Rapu Malcolm and George Meredith Ani Akatauira, and six daughters: Marie Rima Desiree, Mahinarangi Margaret, Bambi Tetianui O Pa Paiaoro, Isabell, Kairangi Elizabeth, and Memory Teariki Tutini Memory Teao Manea.

In 1977, she was awarded the Queen Elizabeth II Silver Jubilee Medal.[9]

After a divorce, in 1979 she married Tom Davis, then Prime Minister of the archipelago, in a Baha'i ceremony. As an ariki, she refused to be called "first lady", saying "I do not mind being addressed as 'queen' but I do object to the 'first lady'. I did not have to marry a politician to become a first lady. I was born a first lady!"[10]

Pa Terito's relations with her husband were sometimes difficult. She repeatedly opposed his political decisions. In March 1986, she openly criticized plans to open a resort in Muri on tribal lands.[11] It seems that the discussion that ensued in the intimacy of the couple turned into a fight, at least that is what the local rumor, very active in the Cook Islands, asserted. The local and New Zealand press also echoed it. Geoffrey Henry took the opportunity to ask for the resignation of Tom Davis, evoking marital violence. Davis then disappeared for a few days. Officially he had accidentally injured himself, suffering from cuts to the ear, chest, and groin, which fed the rumor all the more. A neighbour living near the couple said, on condition of anonymity, "if the cut in the groin had been longer than a half inch, Sir Thomas would today be a soprano in the church of Ngatangiia."[12] This accounting was later denied by Pa Terito, who declared that her husband had injured himself in his sleep by turning onto a hunting knife. The hotel project was abandoned.

Death

Pa Terito died suddenly on 3 February 1990 on a plane that brought her to New Zealand to attend Waitangi Day, which commemorates the Treaty of Waitangi.[4] The Cook Islands had two days of official mourning following her death.[13] Her state funeral was attended by thousands.[14] She was buried according to the Baha'i rite. Her eldest daughter Marie Peyroux succeeded her to the title as Pa Tepaeru Teariki Upokotini Marie Ariki.[4]

Notes

- Sometimes referred to as Pa Tepaeru-a-Tupe

- Levine, Stephen (2016). Pacific Ways: Government and Politics in the Pacific Islands (2nd ed.). Victoria University Press. ISBN 978-1-77656-026-4.

- Kernahan 1995, p. 89.

- "It seems that Pa Terito appointed in 1924, was brought in to the status through the actions of Tupe Short." In re Pa Ariki (2004) CKHC 3; Application 286.2004; 2 July 2004, paragraph 20

- Kernahan 1995, p. 82.

- Kernahan 1995, p. 90.

- Kernahan 1995, p. 92.

- Son of Jean Dominique Peyroux, a French Navy sailor who settled in Rarotonga in the early 20th century

- Taylor, Alister; Coddington, Deborah (1994). "Recipients of the Queen's Silver Jubilee Medal 1977: nominal roll of New Zealand recipients including Cook Islands, Niue and Tokelau". Honoured by the Queen – New Zealand. Auckland: New Zealand Who's Who Aotearoa. p. 431. ISBN 0-908578-34-2.

- Kernahan 1995, p. 83.

- This was an immense project for which the construction between the island and the motu located offshore was foreseen.

- Kernahan 1995, p. 197.

- Haag, John (2002). "Davis, Pa Tepaeru Ariki (1923–1990)". In Commire, Anne (ed.). Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Waterford, Connecticut: Yorkin Publications. ISBN 0-7876-4074-3. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- Kernahan 1995, p. 81.

References

- Kernahan, Mel (1995). White Savages in the South Seas. London: Verso. pp. 81–94. ISBN 978-1-85984-004-7.