Broad-billed prion

The broad-billed prion (Pachyptila vittata) is a small pelagic seabird in the shearwater and petrel family, Procellariidae. It is the largest prion, with grey upperparts plumage, and white underparts. The sexes are alike. It ranges from the southeast Atlantic to New Zealand mainly near the Antarctic Convergence. In the south Atlantic it breeds on Tristan da Cunha and Gough Island; in the south Pacific it breeds on islands off the south coast of South Island, New Zealand and on the Chatham Islands. It has many other names that have been used such as blue-billed dove-petrel, broad-billed dove-petrel, long-billed prion, common prion, icebird, and whalebird.[2]

| Broad-billed prion | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Procellariiformes |

| Family: | Procellariidae |

| Genus: | Pachyptila |

| Species: | P. vittata |

| Binomial name | |

| Pachyptila vittata (Forster, G, 1777) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Procellaria vittata (protonym) | |

Taxonomy

The broad-billed prion was described in 1777 by the German naturalist Georg Forster in his book A Voyage Round the World. He had accompanied James Cook on Cook's second voyage to the Pacific. He included a brief description: "the blue petrel, so called from its having a blueish-grey colour, and a band of blackish feathers across the whole wing." Forster placed the broad-billed prion in the genus Procellaria that had been erected for the petrels by Carl Linnaeus in 1758 and coined the binomial name Procellaria vittata.[3][4] The broad-billed prion is now placed in the genus Pachyptila that was introduced in 1811 by the German zoologist Johann Karl Wilhelm Illiger.[5][6] The genus name combines the Ancient Greek pakhus meaning "dense" or "thick" with ptilon meaning "feather" or "plumage". The specific epithet vittata is from the Latin vittatus meaning "banded".[7] The word "prion" comes from the Ancient Greek priōn meaning "a saw", which is in reference to the serrated edges of the bill.[8]

Members of the genus Pachyptila, together with the blue petrel, make up the prions. They in turn are members of the family Procellariidae, and the order Procellariiformes. The prions are small and typically eat just zooplankton;[2] however as a member of the Procellariiformes, they share certain identifying features. First, they have nasal passages that attach to the upper bill called naricorns. Although the nostrils on the prion are on top of the upper bill. The bills of Procellariiformes are also unique in that they are split into between seven and nine horny plates. They produce a stomach oil made up of wax esters and triglycerides that is stored in the proventriculus. This can be sprayed out of their mouths as a defence against predators and as an energy rich food source for chicks and for the adults during their long flights.[9] Finally, they also have a salt gland that is situated above the nasal passage and helps desalinate their bodies, due to the high amount of ocean water that they imbibe. It excretes a high saline solution from their nose.[10]

Description

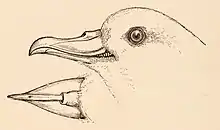

The broad-billed prion has the usual prion colours: blue-grey upperparts, white underparts, and the ever present dark "M" across its back and wings. It has a grey crown, a dark eye stripe, and a black-tipped tail. Its heavy bill is iron-grey but can appear blackish from a distance.[11] The head pattern is more distinct and the tail band is less extensive than that of the similar fairy prion. Its bill has the best developed lamellae of all the prions, allowing it to feed on tiny animals.[12] This is a large prion measuring 25 to 30 cm (9.8 to 11.8 in) long, with a wingspan of 57 to 66 cm (22 to 26 in) and weighing on average 160 to 235 g (5.6 to 8.3 oz).[2]

Distribution and habitat

This species is found throughout oceans and coastal areas in the Southern Hemisphere. Its colonies is found on Gough Island, Tristan da Cunha, South Island, Chatham Islands, on the subantarctic Antipodes Islands, and other islands off the coast of New Zealand.[2][13]

Behaviour

They are social birds; however their courtship displays happen at night or in their burrows. When they need to defend their nests they are very aggressive with calling, posturing, and neck-biting.[2]

Feeding

They are gregarious, and eat crustaceans (copepods), squid, and fish. They utilize a technique called hydroplaning, where the bird flies with its bill in the water, skimming water in, and then filtering the food. They also surface-seize. This prion doesn't follow fishing boats regularly.[2]

Breeding

Breeding begins on the coastal slopes, lava fields, or cliffs of the breeding islands in July or August, as they lay their single egg in a burrow type nest. The clutch is a single white egg which is approximately 50.0 mm × 36.8 mm (1.97 in × 1.45 in).[11] Both parents incubate the egg for 50 days, and then spend another 50 days raising the chick.[2] The main predators are skuas, although on some islands, cats and rats have reduced this prion's numbers drastically. Colonies disperse from December onwards, although some adults remain in the vicinity of the breeding islands and may visit their burrows in winter.[11]

Conservation

This prion has an occurrence range of 10,500,000 km2 (4,100,000 sq mi) and an estimated population of 15 million. It is categorised as least concern by the IUCN.[1]

References

- BirdLife International (2018). "Pachyptila vittata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22698106A132625918. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22698106A132625918.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Maynard, B. J. (2003)

- Forster, Georg (1777). A Voyage Round the World, in His Britannic Majesty's Sloop, Resolution, Commanded by Capt. James Cook, During the Years 1772, 3, 4, and 5. Vol. 1. London: B. White, P. Elmsly, G. Robinson. pp. 91, 98.

- Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 131.

- Illiger, Johann Karl Wilhelm (1811). Prodromus systematis mammalium et avium (in Latin). Berolini [Berlin]: Sumptibus C. Salfeld. p. 274.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (July 2021). "Petrels, albatrosses". IOC World Bird List Version 12.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 288, 404. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Gotch, A. T. (1995)

- Double, M. C. (2003)

- Ehrlich, Paul R. (1988)

- Marchant, S.; Higgins, P.G., eds. (1990). "Pachyptila vittata Broad-billed Prion" (PDF). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic Birds. Vol. 1: Ratites to ducks, Part A, Ratites to petrels. Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. pp. 515–521. ISBN 978-0-19-553068-1.

- Masello, J. F.; Ryan, P. G.; Shepherd, L. D.; Quillfeldt, P.; Cherel, Y.; Tennyson, A. J.; Alderman, R.; Calderón, L.; Cole, T. L.; Cuthbert, R. J.; Dilley, B. J.; Massaro, M.; Miskelly, C. M.; Navarro, J.; Phillips, R. A.; Weimerskirch, H.; Moodley, Y. (2021). "Independent evolution of intermediate bill widths in a seabird clade". Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 297 (1): 183–198. doi:10.1007/s00438-021-01845-3. PMC 8803701. PMID 34921614.

- Clements, James (2007)

Sources

- Harrison, P. (1991) [1983]. Seabirds: an identification guide (2nd ed.). Beckenham, U.K.: Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-7136-3510-X.

- Clements, James (2007). The Clements Checklist of the Birds of the World (6th ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4501-9.

- Double, M. C. (2003). "Procellariiformes (Tubenosed Seabirds)". In Hutchins, Michael; Jackson, Jerome A.; Bock, Walter J.; Olendorf, Donna (eds.). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Vol. 8 Birds I Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins. Joseph E. Trumpey, Chief Scientific Illustrator (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. pp. 107–111. ISBN 0-7876-5784-0.

- Ehrlich, Paul R.; Dobkin, David, S.; Wheye, Darryl (1988). The Birders Handbook (First ed.). New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. pp. 29–31. ISBN 0-671-65989-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gotch, A. F. (1995) [1979]. "Albatrosses, Fulmars, Shearwaters, and Petrels". Latin Names Explained A Guide to the Scientific Classifications of Reptiles, Birds & Mammals. New York, NY: Facts on File. p. 192. ISBN 0-8160-3377-3.

- Maynard, B. J. (2003). "Shearwaters, petrels, and fulmars (Procellariidae)". In Hutchins, Michael; Jackson, Jerome A.; Bock, Walter J.; Olendorf, Donna (eds.). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Vol. 8 Birds I Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins. Joseph E. Trumpey, Chief Scientific Illustrator (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. pp. 123–133. ISBN 0-7876-5784-0.