Palaeoloxodon recki

Palaeoloxodon recki is an extinct species of elephant native to Africa and West Asia from the late Pliocene to Middle Pleistocene. During most of its existence, it represented the dominant elephant species in East Africa.[1]

| Palaeoloxodon recki Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

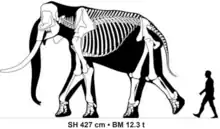

| Size comparison of a 40 year old adult male from Koobi Fora | |

| |

| Life restoration by Mauricio Antón | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Proboscidea |

| Family: | Elephantidae |

| Genus: | †Palaeoloxodon |

| Species: | †P. recki |

| Binomial name | |

| †Palaeoloxodon recki (Dietrich, 1894) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Elephas recki Dietrich, 1894 | |

Description

Members of the species were larger than any living elephant. A large mostly complete male specimen of P. recki from Koobi Fora, Kenya, suggested to have been approximately 40 years old when it died, was estimated in a 2016 study to have measured 4.27 metres (14.0 ft) tall and weighed 12.3 tonnes (12.1 long tons; 13.6 short tons).[2] In comparison to most Eurasian species of Palaeoloxodon, the parieto-occipital crest at the top of the skull is only weakly developed. The frons (forehead) is tall and biconvex.[3] Over time the molar teeth of P. recki show an increasing number of lamellae, and taller crown height (hypsodonty).[4]

Evolutionary history

The earliest P. recki specimen is the subject to uncertainity, due to the debate about what specimens are actually applicable to the species.[3] At the end of the Early Pleistocene, a population of P. recki migrated out of Africa, giving rise to the Eurasian radiation of Palaeoloxodon.[5] Its descendant taxon or last evolutionary stage, Palaeoloxodon iolensis, is known from remains found across Africa of late Middle Pleistocene to Late Pleistocene age. Both P. recki and P. iolensis are thought to have been grazers, based on isotopic and morphological evidence. Following the extinction of P. iolensis it was replaced by the modern African bush elephant (Loxodonta africana).[1]

Taxonomy

The species was initially named from specimens found at Bed IV in Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania by Wilhelm Otto Dietrich in 1915, originally as a subspecies of the European straight-tusked elephant, what is now called Palaeoloxodon antiquus, as Elephas antiquus recki. Arambourg in 1942 described additional specimens of the species from Omo Valley in Ethiopia, and suggested that they were distinctive enough that they warranted being placed as the distinct species E. recki. The two deposits are not contemporaneous and the specimens from each locality are morphologically distinctive from each other, which has led to confusion about which locality represents the "typical" morphology of the species.[6] M. Beden [7][8][9] identified five subspecies of Palaeoloxodon recki, from oldest to youngest:

- P. r. brumpti Beden, 1980

- P. r. shungurensis Beden, 1980

- P. r. atavus Arambourg, 1947

- P. r. ileretensis Beden, 1987

- P. r. recki (Dietrich, 1916)

New research indicates that the ranges for all five subspecies overlap, and that they are not separated in time as previously proposed. The research also found a wide range of morphological variation, both between the supposed subspecies and between different specimens previously identified as belonging to the same subspecies. The degree of temporal and geographical overlap, along with the morphological variation in P. recki suggests that the relationships between any subspecies are more complicated than previously indicated.[10][6] While previously placed in Elephas, most modern researchers place the species within Palaeoloxodon. Contemporary research has questioned the attribution of many specimens of Palaeoloxodon recki to the species,[11] with a preliminary phylogenetic analysis done in 2018 finding that some remains attributed to P. recki (including the proposed subspecies P. r. brumpti and P. r. atavus) were more closely related to Elephas and Mammuthus, leading to the suggestion that E/P. recki in its broader sense is a wastebasket taxon, though the type material from Olduvai Gorge is clearly assignable to Palaeoloxodon, [12] alongside other material from Kenya, Ethiopia and Eritrea. It has also been suggested that material from West Asia, including that from the earliest Middle Pleistocene (c. 780,000 years ago) Paleolithic archaeological site Gesher Bnot Ya'akov (otherwise attributed to P. antiquus) in northern Israel, the Middle Pleistocene (c. 500,000 years ago) Ti’s al Ghadah site in northern Saudi Arabia, and the late Middle Pleistocene Shishan Marsh site in Jordan, belong to P. recki.[3][13][14]

Relationship with humans

At several sites across Africa, remains of P. recki have been found associated with stone tools. In some cases like Olduvai FLK, these are likely co-incidental, but in others which bears cut marks, these likely represent evidence of butchery by archaic humans. Sites containing P. recki remains with cut marks and/or stone tools include Upper Bed II at the Bell’s Korongo site in Olduvai Gorge, dating to around 1.35 million years ago, which has been suggested to be the oldest site in the world with reliable evidence of elephant butchery, associated with Oldowan-type stone tools, and the Olorgesailie Basin Member 1 Site 15 in Kenya, dated to 992–974,000 years ago, and the Nadung’a 4 site near Lake Turkana, Kenya, dating to approximately 700,000 years ago. The Barogali site in Dijbouti, dating to 1.6-1.3 million years ago, where a disassociated specimen of P. recki was found with numerous stone tools (probably Oldowan) created onsite, has also been suggested to show evidence of butchery. The P. antiquus/P. recki specimen from Gesher Bnot Ya'akov is associated with an Acheulean stone handaxe and other bifaced tools, and displays cut marks and fracture marks indicative of butchery, though the fracturing of the skull, which has been suggested to be the result of an attempt to extract the brain, may alternatively be the result of postmortem trampling.[15]

Gallery

Skull at the Gallery of Paleontology and Comparative Anatomy, France

Skull at the Gallery of Paleontology and Comparative Anatomy, France Underside of the skull and lower jaws at the Gallery of Paleontology and Comparative Anatomy

Underside of the skull and lower jaws at the Gallery of Paleontology and Comparative Anatomy Lower jaw at the Museum für Naturkunde. Berlin

Lower jaw at the Museum für Naturkunde. Berlin

References

- Manthi, Fredrick Kyalo; Sanders, William J.; Plavcan, J. Michael; Cerling, Thure E.; Brown, Francis H. (September 2020). "Late Middle Pleistocene Elephants from Natodomeri, Kenya and the Disappearance of Elephas (Proboscidea, Mammalia) in Africa". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 27 (3): 483–495. doi:10.1007/s10914-019-09474-9. ISSN 1064-7554. S2CID 198190671.

- Larramendi, A. (2016). "Shoulder height, body mass and shape of proboscideans" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 61. doi:10.4202/app.00136.2014.

- Larramendi, Asier; Zhang, Hanwen; Palombo, Maria Rita; Ferretti, Marco P. (February 2020). "The evolution of Palaeoloxodon skull structure: Disentangling phylogenetic, sexually dimorphic, ontogenetic, and allometric morphological signals". Quaternary Science Reviews. 229: 106090. Bibcode:2020QSRv..22906090L. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.106090. S2CID 213676377.

- Lister, Adrian M. (2013-06-26). "The role of behaviour in adaptive morphological evolution of African proboscideans". Nature. 500 (7462): 331–334. Bibcode:2013Natur.500..331L. doi:10.1038/nature12275. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 23803767. S2CID 883007.

- Lister, Adrian M. (2004), "Ecological Interactions of Elephantids in Pleistocene Eurasia", Human Paleoecology in the Levantine Corridor, Oxbow Books, pp. 53–60, ISBN 978-1-78570-965-4, retrieved 2020-04-14

- Todd, Nancy E. (January 2005). "Reanalysis of African Elephas recki: implications for time, space and taxonomy". Quaternary International. 126–128: 65–72. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2004.04.015.

- Beden, M. 1980. Elephas recki Dietrich, 1915 (Proboscidea, Elephantidae). Èvolution au cours du Plio-Pléistocène en Afrique orientale]. Geobios 13(6): 891-901. Lyon.

- Beden, M. 1983. Family Elephantidae. In J. M. Harris (ed.), Koobi Fora Research Project. Vol. 2. The fossil Ungulates: Proboscidea, Perissodactyla, and Suidae: 40-129. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Beden, M. 1987. Les faunes Plio-Pléistocène de la basse vallée de l’Omo (Éthiopie), Vol. 2: Les Eléphantidés (Mammalia-Proboscidea) (directed by Y. Coppens and F. C. Howell): 1-162. Cahiers de Paléontologie-Travaux de Paléontologie est-africaine. Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS). Paris.

- Todd, N. E. 2001. African Elephas recki: Time, space and taxonomy. In: Cavarretta, G., P. Gioia, M. Mussi, and M. R. Palombo. The World of Elephants, Proceedings of the 1st International Congress. Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche. Rome, Italy. Online pdf Archived 2008-12-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Larramendi, Asier; Zhang, Hanwen; Palombo, Maria Rita; Ferretti, Marco P. (February 2020). "The evolution of Palaeoloxodon skull structure: Disentangling phylogenetic, sexually dimorphic, ontogenetic, and allometric morphological signals". Quaternary Science Reviews. 229: 106090. Bibcode:2020QSRv..22906090L. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.106090. S2CID 213676377.

- H. Zhang Elephas recki: the wastebasket? 66th Symposium of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Comparative Anatomy, Manchester. (2018)

- Stimpson, Christopher M.; Lister, Adrian; Parton, Ash; Clark-Balzan, Laine; Breeze, Paul S.; Drake, Nick A.; Groucutt, Huw S.; Jennings, Richard; Scerri, Eleanor M.L.; White, Tom S.; Zahir, Muhammad; Duval, Mathieu; Grün, Rainer; Al-Omari, Abdulaziz; Al Murayyi, Khalid Sultan M. (July 2016). "Middle Pleistocene vertebrate fossils from the Nefud Desert, Saudi Arabia: Implications for biogeography and palaeoecology". Quaternary Science Reviews. 143: 13–36. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2016.05.016.

- Pokines, James T.; Lister, Adrian M.; Ames, Christopher J. H.; Nowell, April; Cordova, Carlos E. (March 2019). "Faunal remains from recent excavations at Shishan Marsh 1 (SM1), a Late Lower Paleolithic open-air site in the Azraq Basin, Jordan". Quaternary Research. 91 (2): 768–791. doi:10.1017/qua.2018.113. ISSN 0033-5894.

- Haynes, Gary (March 2022). "Late Quaternary Proboscidean Sites in Africa and Eurasia with Possible or Probable Evidence for Hominin Involvement". Quaternary. 5 (1): 18. doi:10.3390/quat5010018. ISSN 2571-550X.