Israeli identity card

Teudat Zehut (Hebrew: תעודת זהות t'udát zehút; Arabic: بطاقة هوية biṭāqat huwiyyah) is the Israeli compulsory identity document issued by the Ministry of Interior, as prescribed in the Identity Card Carrying and Displaying Act of 1982: "Any resident sixteen years of age or older must at all times carry an Identity card, and present it upon demand to a senior police officer, head of Municipal or Regional Authority, or a policeman or member of the Armed forces on duty."[2] According to a precedent from 2011, residents are entitled to refuse presenting the card, unless the state-official has a reason to suspect that they have committed an offence.[3]

| Teudat Zehut תעודת זהות بطاقة هوية | |

|---|---|

The front side of a contemporary biometric Israeli identity card | |

The reverse side of a contemporary biometric Israeli identity card | |

| Type | National identity card |

| Issued by | |

| First issued | 1948 2013 (Biometric) |

| Purpose | Identification |

| Eligibility | 16 years of age All Israeli citizens, legal permanent or temporary residence status (including non-citizens) |

| Expiration | 10 years after acquisition. Or, in the case of non-biometric identity cards, the expiration date is no later than August 2024. The expiration dates of identity cards issued to foreign nationals is linked to the validity of their visa. |

| Cost | Free or ₪130 to replace a lost identity card.[1] |

Law and common practice

It is a criminal offence to not carry an identity card or to misuse the document and a person can be fined about ₪1,400 as of 2016. However, the law explicitly forbids pressing charges if the offender contacts the relevant authorities within five days and identifies him or herself properly.

Furthermore, in December 2011, a Peace Court (Magistrate Court) in the Krayot region acquitted an Israeli citizen from Nahariya who refused to present his identity card to a policeman upon request. The judge ruled that the current interpretation of law must be in the spirit of the Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty (enacted in 1992); such a refusal should be deemed legitimate unless the state-official has a reason to suspect that the person before them has committed an offence.[3]

In addition to the above law, the identity card is required in order to exercise certain civil rights. Until recently, it was the only valid identification for voting in general elections. However, since 2005, the law also permits the use of a valid driver's license or a valid Israeli passport.[4]

When not specifically required by law, other identification may be used. In Israel, access to many office buildings or guarded areas requires showing ID.[5]

Identity cards are issued by the Israeli Ministry of Interior through offices across the country. The document is issued to all residents over 16 years old who have legal permanent residence status, including non-citizens. Up until July 2012, the document had no expiry date, and it could be used as long as it was intact. All non-biometric identity cards will expire after 10 years or in July 2022, whichever date is earlier.[6] Identity cards issued to temporary residents have the same duration as the visa that grants temporary residence to the person in question, usually one year.

Document contents

The card is credit card sized and includes the following personal details:

- Identity number (Mispar Zehut) comprising nine digits, the last of which is a check digit calculated using the Luhn algorithm

- Full name (surname(s), given name(s))

- Filiation (the legal ascendant(s))

- Date of birth (both civil and, unless otherwise requested, Hebrew date as well)

- Status

- Sex

- Place and date of issue (both Gregorian and Hebrew dates)

- Portrait photo (in color)

- Previous name(s) (if applicable)

- Status (citizen, permanent residency, temporary)

- Name, birth date and identity number of spouse and children(s) (if applicable)

Question of ethnicity

Prior to 2005, Identity Cards included a reference to the bearer's ethnic group. The official term for this category in Hebrew was le'om (לאום), and it was officially translated into Arabic as qawmīya (قومية). These terms could be translated into English as "nation" but in the sense of ethnic affiliation. The le'om attribution was assigned by the Ministry of Interior regardless of the card bearer's preference. There were several attributions, the main ones being Jewish, Arab, Druze and Circassian. Identity Cards issued before 2005 included a disclaimer written in small print in Hebrew and Arabic indicating that the card may serve as a prima facie proof for the data that it includes except le'om, marital status and the spouse's name.

There were fierce legal battles about identifying the ethnicity of the bearer in the Israeli Identity card. In the 2000s, the ethnicity indicator began to be officially phased out. In 2002, the Supreme Court of Israel instructed the Ministry of Interior to indicate the ethnicity of people who underwent a Reform conversion as Jews. The minister at the time, Eli Yishai, a member of Shas, a Haredi party, decided he would drop the ethnicity category altogether, rather than list as Jews people whom he considered non-Jews. In 2004, the Supreme Court denied a citizen's petition to reinstate this indicator, stating that the field in the document was meant for statistical collection only, not as a declarative statement of Judaism. As of 2005, the ethnicity has not been printed; a line of eight asterisks appears instead. The bearer's ethnic identity can nevertheless be inferred by other data: the Hebrew calendar's date of birth is often used for Jews, and each community has its own typical first and last names.

As of 2015, the ethnicity has been completely removed (including the asterisks), and replaced by status - which defines whether a person is a citizen, permanent or temporary resident.

An amendment to the Israeli registration law approved by the Knesset in 2007 determines that a Jew may ask to remove the Hebrew date from his entry and consequently from his Identity Card. That is due to errors that often occur in the registration of the Hebrew date because the Hebrew calendar day starts at sunset, not at midnight. The amendment also introduces an explicit definition for the term "a day according to the Hebrew calendar".

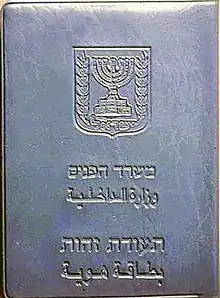

ID card casing and variations

The colour of the plastic casing for the non-biometric identity cards of Israeli citizens and permanent residents was blue, with the Israeli Coat of Arms embossed on the outer cover. The casing of cards belonging to temporary residents is the same as the one of citizens and permanent residents, while the card itself has a pink hue. Non-Israeli residents of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip were issued ID cards by the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories, which had an almost identical layout as the Israeli card (the differences being that the surname came after the given name, and legal ascendant(s) name(s) instead of at the top, and the "ethnicity" category was replaced with a "religion" category).

The casings for those cards were orange (West Bank) or red (Gaza Strip) with the Israel Defense Forces insignia embossed on the outer cover. Palestinians barred from entering Israel were issued ID cards with green casings instead of orange to identify them as such. Since the establishment of the Palestinian National Authority, the PNA issues its residents with Palestinian ID cards based on Israeli approval. They are identical to the Israeli Civil Administration cards except for the order of languages being switched, Arabic coming before Hebrew, and the plastic casing being dark green with the PNA insignia embossed on the outer cover. Israel controls the Palestinian population registry per the Interim Agreements, and assigns the ID numbers for Palestinian ID cards.

Israel began issuing ID cards to Palestinian residents of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip following their capture in the 1967 war.

See also

References

- "Issue of ID card". 22 September 2023.

- חוק החזקת תעודת זהות והצגתה (Identity Card Carrying and Displaying Law of 1982) on the Hebrew Wikisource.

- Court: There is no Obligation to Present an Identity Card upon a Policeman's Request, by Revital Hovel, Haaretz, 5 Dec 2011 (in Hebrew).

- Amendment no. 54 to article no. 74 of the Election Law, approved by the Knesset on December 5, 2005.

- For example, the Al-Aqsa mosque area in Jerusalem, Azrieli Towers in Tel Aviv, Aviv Towers in Ramat Gan and many others.

- "Nevo.co.il". www.nevo.co.il. Retrieved 2016-08-28.