Palo (religion)

Palo, also known as Las Reglas de Congo, is an African diasporic religion that developed in Cuba during the late 19th or early 20th century. It arose through a process of syncretism between the traditional Kongo religion of Central Africa, the Roman Catholic branch of Christianity, and Spiritism. Initiates in the religion are termed paleros (male) or paleras (female).

An initiatory religion, Palo is organised through small autonomous groups called munanso congo, each led by a figure known as a tata (father) or yayi (mother). Although teaching the existence of a creator deity, Nsambi or Sambia, Palo regards this entity as being uninvolved in human affairs and thus focuses its attention on the spirits of the dead, collectively known as Kalunga. Central to Palo is the nganga or prenda, a vessel usually made from an iron cauldron, clay pot, or gourd. Many nganga are regarded as material manifestations of particular deities known as mpungu. The nganga will typically contain a wide range of objects, among the most important being sticks and human remains, the latter called nfumbe. In Palo, the presence of the nfumbe means that the spirit of the dead person inhabits the nganga and serves the palero or palera who keeps it. The Palo practitioner commands the nfumbe, through the nganga, to do their bidding, typically to heal but also to cause harm. Those nganga primarily designed for benevolent acts are baptised; those largely designed for malevolent acts are left unbaptised. The nganga is "fed" with the blood of sacrificed animals and other offerings, while its will and advice is interpreted through various forms of divination.

Palo developed among Afro-Cuban communities following the Atlantic slave trade of the 16th to 19th centuries. It formed through the blending of the traditional religions brought to Cuba by enslaved Bakongo people from Central Africa with ideas from Roman Catholicism, the only religion legally permitted on the island by the Spanish colonial government. The minkisi, spirit vessels that were key to various Kongolese healing societies, provided the basis for the nganga of Palo. The religion took its distinct form around the late 19th or early 20th century, about the same time that Yoruba religious traditions merged with Roman Catholic and Spiritist ideas in Cuba to produce Santería. After the Cuban War of Independence resulted in an independent republic in 1898, its new constitution enshrined freedom of religion. Palo nevertheless remained marginalized by Cuba's Roman Catholic, Euro-Cuban establishment, which typically viewed it as brujería (witchcraft), an identity that many Palo practitioners have since embraced. In the 1960s, growing emigration following the Cuban Revolution spread Palo abroad.

Palo is divided into multiple traditions or ramas, including Mayombe, Monte, Briyumba, and Kimbisa, each with their own approaches to the religion. Many practitioners also identify as Roman Catholics and practice additional Afro-Cuban traditions such as Santería. Palo is most heavily practiced in eastern Cuba although is found throughout the island and has spread abroad, including in other parts of the Americas such as Venezuela, Mexico, and the United States. In many of these countries, Palo practitioners have clashed with law enforcement for engaging in grave robbery to procure human bones for their nganga.

Definitions

Palo is an Afro-Cuban religion,[1] and more broadly an Afro-American religion.[2] Its name derives from palo, a Spanish term for sticks, referencing the important role that these items play in the religion's practices.[3] Another term for the religion is La Regla de Congo ("Kongo Rule" or "Law of Kongo") or Regla Congo, a reference to its origins among the traditional Kongo religion of Central Africa's Bakongo people.[4] Palo is also sometimes referred to as brujería (witchcraft), both by outsiders and by some practitioners themselves.[5]

Although its origins draw heavily on Kongo religion, Palo also takes influence from the traditional religions of other African peoples who were brought to Cuba, such as the West African Yoruba. These African elements combined with elements from Roman Catholicism and also from Spiritism, a French variant of Spiritualism.[6] The idea of Palo having African origins is important to practitioners. They often refer to their religious homeland as Ngola,[7] indicating a belief in the historical Kingdom of Kongo as Palo's place of origin, a place where the spirits are more powerful.[8]

Palo has no sacred text,[9] but is largely transmitted orally.[10] There is no central authority in control of the religion,[11] but separate groups of practitioners who operate autonomously.[12] It has no systematized doctrine,[10] and no strict ritual protocol,[9] giving its practitioners scope for innovation and change.[12] Different practitioners often interpret the religion differently,[13] resulting in highly variable practices.[9] Several distinct traditions or denominations of Palo exist, called ramas, with the main ramas being Mayombe, Briyumba, Monte, and Kimbisa.[14]

Palo is one of three major Afro-Cuban religions present on the island, the other two being Santería, which derives largely from the Yoruba religion of West Africa, and Abakuá, which has its origins among the secret male societies practiced among the Efik-Ibibio.[15] Many Palo initiates are also involved in Santería,[16] Abakuá,[17] Spiritism,[18] or Roman Catholicism.[19] Practitioners will often see these different religions as offering complementary skills and mechanisms to solve problems.[20] Some practitioners of Palo believe that the religion's adherents should be baptised Roman Catholics.[21] Generally an individual is initiated into Santería after they have been initiated into Palo; the reverse is not normally permitted.[22] There are some Palo practitioners who object to the introduction of elements from Santería in their religion.[23] Palo also has commonalities with Obeah, a practice originating largely in Jamaica, and it is possible that Palo and Obeah cross-fertilised via Jamaican migration to Cuba from 1925 onward.[24]

Terms for practitioners

Practitioners are usually termed paleros if male,[25] paleras in female,[26] terms which can be translated as "one who handles tree branches."[27] An alternative term for adherents is mayomberos.[28] Another term applied to Palo practitioners in Cuba is ngangulero and ngangulera, meaning "a person who works a nganga."[29] The term carries pejorative connotations in Cuban society although some practitioners adopt it as a term of pride.[30] A similarly pejorative term embraced by some adherents is brujo (witch).[31]

Beliefs

Deities and spirits

Although Palo lacks a full mythology,[12] its worldview includes a supreme creator divinity, Nsambi or Sambia.[32] In the religion's mythology, Nsambi is believed responsible for creating the first man and woman.[33] This entity is regarded as being remote from humanity and thus no prayers or sacrifices are directed towards it.[33] The anthropologist Todd Ramón Ochoa, an initiate of Palo Briyumba, described Nsambi as "the power in matter that pushes back against human manipulation and imposes itself against a person's will".[34]

In Palo, the spirits of both ancestors and of the natural world are termed mpungus.[35] The anthropologist Katerina Kerestetzi referred to these as "a sort of minor divinity".[36] Among the most prominent of these mpungu, at least in Havana, are Lucero, Sarabanda, Siete Rayos, Ma' Kalunga, Mama Chola, Centella Ndoki, and Tiembla Tierra.[37] Others include Nsasi and Baluandé.[7] Certain spirits may also have different aspects or manifestations, which each have their own specific names.[7] Trees are considered to be favored abodes of many spirits,[38] and uncultivated areas of forest are regarded as being especially potent locations of spiritual power.[39] Practitioners are expected to make agreements with the spirits of trees and rivers.[40] The scholar Judith Bettelheim described Palo as being "centered on assistance from ancestors and a relationship with the earth, one's land, one's home."[40]

Deities play a much less important role in Palo than they do in Santería.[41] The spirit pact made in Palo is more occasional and intermittent than the relationship that practitioners of Santería make with their deities, the oricha.[42] The spirits of Palo are generally considered fierce and unruly.[22] Practitioners who work with both the oricha and the Palo spirits are akin to those practitioners of Haitian Vodou who conduct rituals for both the Rada and Petwo branches of the lwa spirits; the oricha, like the Rada, are even-tempered, while the Palo spirits, like the Petwo, are more chaotic and unruly.[22]

Spirits of the dead

The spirits of the dead play a prominent role in Palo,[43] with Kerestetzi observing that one of Palo's central features was its belief that "the spirits of the dead mediate and organize human action and rituals."[9] In Palo, a spirit of the dead is referred to as a nfumbe (or nfumbi),[44] a term which derives from the Kikongo word for a dead person, mvumbi.[45] Alternative terms used for the dead in Palo include the Yoruba term eggun[46] as well as Spanish words like el muerto ("the dead")[47] and, more rarely, espíritu ("spirit").[48] Practitioners will sometimes refer to themselves, as living persons, as the "walking dead".[12] The dead may also be referred, especially in a collective sense, as Kalunga.[49]

Palo teaches that the individual comprises both a physical body and a spirit termed the sombra ("shade").[33] In Palo belief, these are connected via a cordón de plata ("silver cord").[33] In Cuba, the Bakongo notion of the spirit "shadow" has merged with the Spiritist notion of the perisperm, a spirit-vapor surrounding the human body.[33] Paleros/paleras venerate the souls of their ancestors;[33] when a group feast is held, the ancestors of the house will typically be invoked and their approval to proceed requested.[50] The dead are regarded as having supernatural powers and knowledge such as prescience.[9] It is held that ancestors can contact and assist the living,[22] but the dead are also thought capable of causing problems for the living, often being blamed for problems like anxiety and sleeplessness.[51]

Palo's practitioners are expected to interact and receive messages from the dead, and if possible to influence the will of the dead for their own personal benefit.[12] Some practitioners claim an innate capacity to sense the presence of spirits of the dead.[52] To ascertain the consent of the dead, Palo's practitioners will often employ divination or forms of spirit mediumship from Spiritism,[50] and in communicating with the dead are sometimes termed muerteros ("mediums of the dead").[53]

In Palo, the dead are often viewed as what Ochoa called "a dense and indistinguishable mass" rather than as discrete individuals.[54] Ochoa defined Kalunga as "a place of immanence from which Palo and its myriad forms of the dead emerge".[55] They are also believed capable of existing within physical matter.[49] They can for instance be represented by small assemblages of material, often found objects or those commonly found in a household, which are placed together, often in the corner of the patio or an outhouse. They are often called rinconcito ("little corners").[56] Offerings of food and drink are often placed at the rinconcito and allowed to decay.[57] This is a practice also maintained by many followers of Santería,[58] although the emphasis placed on the material presence of the dead differs from the Spiritist views of deceased spirits.[59]

The Nganga

A key role in Palo is played by a vessel called the nganga,[28] a term which in Central Africa referred not to an object but to a man who oversaw religious rituals.[60] This vessel is also commonly known as the prenda, a Spanish term meaning "treasure" or "jewel."[61] Alternative terms that are sometimes used for it are el brujo ("the sorcerer"),[41] the enquisa,[62] the caldero (cauldron),[63] or the casuela (pot),[60] while a small, portable version is termed the nkuto.[64] A practitioner may switch between these synonyms during a conversation.[65] On rare occasions, a practitioner may also refer to the nganga as a nkisi (plural minkisi).[63] The minkisi are Kongolese ritual objects believed to possess an indwelling spirit and are the basis of the Palo nganga tradition,[66] the latter being a "uniquely Cuban" development.[67]

The nganga comprises either a clay pot,[68] gourd,[7] or an iron pot or cauldron.[69] This is often wrapped tightly in heavy chains.[70] Every nganga is physically unique,[71] bearing its own individual name;[72] some are deemed male, others female.[73] It is custom that the nganga should not stand directly on either a wooden or tile base, and for that reason the area beneath it is often packed with bricks and earth.[74] The nganga is kept in a domestic sanctum, the munanso,[75] or cuarto de fundamento.[76] This may be a cupboard,[77] a room in a practitioner's house,[77] or an external structure in the practitioner's backyard.[78] This may be decorated in a way that alludes to the forest, for instance with the remains of animal species that live in forest areas, as the latter are deemed abodes of the spirits.[79] When an individual practices both Palo and Santería, they typically keep the spirit vessels of the respective traditions separate, in different rooms.[80]

Terms like nganga and prenda designate not only the vessel but also the spirit believed to inhabit it.[81] For many practitioners, the nganga is regarded as a material manifestation of a mpungu deity.[82] Different mpungu will lend different traits to the nganga; Sarabanda for instance imbues it with his warrior skills.[83] The choice of nganga vessel can be determined depending on the associated mpungu,[40] while the specific mpungu will be linked to the nganga by a particular type of stone that may be placed in it and a symbol, the firma, which is drawn onto it.[36] The name of the nganga may refer to the indwelling mpungu; an example would be a nganga called the "Sarabanda Noche Oscura" because it contains the mpungu Sarabanda.[36] The nganga is deemed to be alive;[84] Ochoa commented that, in the view of Palo's followers, the ngangas were not static objects, but "agents, entities, or actors" with an active role in society.[85] They are believed to express their will to Palo's practitioners both through divination and through spirit possession.[86]

Palo revolves around service and submission to the nganga.[87] Kerestetzi observed that in Palo, "the nganga is not an intermediary of the divine, it is the divine itself[...] It is a god in its own right."[36] Those who keep ngangas are termed the perros (dogs) or criados (servants) of the vessel.[88] The relationship that a Palo practitioner develops with their nganga is supposed to be lifelong,[89] and a common notion is that the keeper becomes like their nganga.[90] Senior practitioners may have multiple ngangas, some of which they have inherited from their own teachers.[77] Some practitioners will consult their nganga to help them make decisions in life, deeming it omniscient.[91] The nganga desires its keeper's attention;[92] it is believed that they often become jealous and possessive of their keepers.[93] Ochoa characterised the relationship between the palero/palera and their nganga as a "struggle of wills",[94] with the Palo practitioner looking upon the nganga with "respect based on fear".[95]

The nganga is regarded as the source or a palero or palera's supernatural power.[96] Within the religion's beliefs, it can both heal and harm,[97] and in the latter capacity is thought capable of causing misfortune, illness, and death.[98] Practitioners believe that the better a nganga is cared for, the stronger it is and the better it can protect its keeper,[89] but at the same time the more it is thought capable of dominating its keeper,[94] and potentially even killing them.[99] Various stories circulating the Palo community tell of practitioners driven to disastrous accidents, madness, or destitution.[100] Stories of a particular nganga's rebelliousness and stubbornness contribute to the prestige of its keeper, as it indicates that their nganga is powerful.[92]

Fundamentos

The contents of the nganga are termed the fundamentos,[101] and are believed to contribute to its power.[102] A key ingredient are sticks, termed palos, which are selected from specific species of tree.[103] The choice of tree selected indicates the sect of Palo involved,[104] with the sticks believed to embody the properties and powers of the trees from which they came.[27] Soil from various locations is added, for instance from a graveyard, hospital, prison, and a market,[105] as may water from various sources, including a river, well, and the sea.[106] A matari stone, representing the specific mpungu linked to that nganga, may be incorporated.[107] Other material added can include animal remains, feathers, shells, plants, gemstones, coins, razorblades, knives, padlocks, horseshoes, railway spikes, blood, wax, aguardiente liquor, wine, quicksilver, and spices.[108] Objects that are precious to the owner, or which have been obtained from far away, may be added,[109] and the harder that these objects are to obtain, the more significant they are often regarded.[110] This varied selection of material can result in the nganga being characterised as a microcosm of the world.[111]

The precise form of the nganga, such as its size, can reflect the customs of the different Palo traditions.[112] Ngangas in the Briyumba tradition are for instance characterised by a ring of sticks extending beyond their rim.[113] Objects may also be selected for their connection with the indwelling mpungu. A nganga of Sarabanda for instance may feature many metal objects, reflecting his association with metals and war.[114] As more objects are added over time, typically as offerings, the quantity of material will often spill out from the vessel itself and be arranged around it, sometimes taking up a whole room.[115] Objects being used in Palo healing and hexing rituals, such as small packages or dolls, may also be temporarily placed near to the nganga to ensure their effectiveness.[116] The mix of items produces a strong, putrid odour and attracts insects,[117] with Ochoa describing the ngangas as being "viscerally intimidating to confront".[77]

The Nfumbe

Human bones will also typically be included in the nganga.[118] Some traditions, like Briyumba, consider this an essential component of the vessel;[119] other practitioners feel that soil or a piece of clothing from a grave may suffice.[120] Practitioners will often claim that their nganga contains human remains even if it does not.[121] The most important body part for this purpose is the skull, termed the kiyumba.[122] The human bones are termed the nfumbe, a Palo Kikongo word meaning "dead one"; it characterises both the bones themselves and the dead person they belonged to.[119]

The bones are selected judiciously; the sex of the nfumbe is typically chosen to match the gender of the nganga it is being incorporated into.[123] Sometimes, the bones of a criminal or mad person are deliberately sought.[23] If bones of a deceased person are unavailable then soil from a dead individual's grave may suffice.[75] According to Palo tradition, a practitioner should exhume the bones from a graveyard themselves, although in urban areas this is often impractical and practitioners instead obtain them through black market agreements with the groundskeepers and administrators responsible for maintaining cemeteries.[124] Elsewhere, human remains that previously served as anatomical teaching specimens have been obtained, or purchased through botanicas.[125]

By tradition, a Palo practitioner would travel to a graveyard at night. There, they would focus on a specific grave and seek to communicate with the spirit of the dead person buried there, typically through divination.[126] They then determine to create a trata (pact) with the spirit, whereby the latter agrees to become the servant of the practitioner. Once they believe that they have the consent of the spirit, the palero/palera will dig up the bones of the deceased, or at least collect soil from their grave, and take it back home. There, they perform rituals to install this spirit inside their nganga.[75] After being removed from their grave, the bones of the nfumbe may undergo attempts to "cool" and settle them, before they are added to the nganga,[127] something that cerré el pacto ("seals the pact").[128]

In Palo, it is believed that the spirit of the dead individual resides in the nganga.[41] This becomes a slave of the owner,[129] making the relationship between the palero/palera and their nfumbe quite different from the reciprocal relationship that the santero/santera has with their oricha in Santería.[22] The keeper of the nganga promises to feed the nfumbe, for instance with animal blood, rum, and cigars.[130] The nfumbe spirit will then protect the keeper,[104] and carries out the commands of their owner or their owner's clients;[131] its services are termed trabajos.[132] Practitioners will sometimes talk of their nfumbe having a distinct personality, displaying traits such as stubbornness or jealousy.[128] The nfumbe will rule over other spirits, of animals and plants, that are also included in the nganga.[104] Specific animal parts added are believe to enhance the skills of the nfumbe in the nganga;[133] a bat's skeleton for instance might be seen as giving the nfumbe the ability to fly through the night to conduct errands,[117] a turtle would give it a ferocious bite,[83] and a dog's head would give it a powerful sense of smell.[134]

Ngangas cristiana and judía

The nganga are generally divided into two categories, the cristiana (Christian) and the judía (Jewish).[135] The use of the terms cristiana and judía in this context reflect the influence of 19th-century Spanish Catholic ideas about good and evil,[136] with the term judía connoting something being non-Christian rather than being specifically associated with Judaism.[137] Nganga cristianas will be deemed "baptised" because holy water from a Roman Catholic church will be included as one of their ingredients;[138] they may also include a crucifix.[139] The human remains included as a nfumbe within them is also expected to be that of a Christian.[138] While nganga cristianas can be used to counter-strike against attackers, they are prohibited from killing people.[138] Conversely, nganga judías are used for trabajos malignos, or harmful work,[140] and specifically are capable of killing people.[141] The human remains included in nganga judías are typically those of a non-Christian, although not necessarily of a Jew specifically.[142] The boundaries between the two types of nganga are not always wholly fixed, because the baptised nganga can still be used for harmful work on rare occasions.[143]

Many practitioners maintain that the two different kinds of nganga should be kept apart from each other, for otherwise the two will fight.[144] Unlike ngangas cristianas, who only receive the blood of their keeper at the latter's initiation, ngangas judías will be fed their keeper's blood more often.[145] Palo tradition also holds that the nganga judía are prone to betraying their keeper and to come for the latter's blood.[146] Those observing Palo in Cuba during the 1990s, including Ochoa and the medical anthropologist Johann Wedel, noted that judía ngangas were rare by that point.[147]

Palo teaches that although the nganga judías are more powerful, they are less effective.[148] This is because most of the time, nganga judías are scared of the nganga cristianas and thus vulnerable to them, but that one day of the year this changes - Good Friday. In Christian belief, Good Friday marks the day on which Jesus Christ was crucified and died, and thus paleros and paleras believe that the power of the nganga cristianas is nullified temporarily. Good Friday is therefore the day on which nganga judías may be used.[149] On Good Friday, a white sheet will often be placed over any nganga cristianas so as to keep them "cool" and protect them during this vulnerable period.[148]

Creating a nganga

The nganga does not merely transcend different ontological categories, it also blurs common oppositions, for example between living and dead, material and immaterial, sacred and profane. It is a living being but its main component is a dead man; it overflows with materiality but its body represents an invisible being; its word is infallible but its personality is drawn from the history of an ordinary person.

— Anthropologist Katerina Kerestetzi[150]

The making of a nganga is a complex procedure.[104] It can take several days,[151] with its components occurring at specific times during the day and month.[104] When a new nganga is created for a padre or madre, it is said to be nacer ("sprung" or "born") from the "mother" nganga which rules the house.[152] The first nganga of a tradition, from which all others ultimately stem, is called the tronco ("trunk").[8] The process of creating a new nganga is often kept secret, amid concerns that if a rival Palo practitioner learns the exact ingredients of the particular nganga, it will leave the latter vulnerable to supernatural attacks.[153] The senior practitioner creating the nganga may ask a madre or padre to assist them, something considered a great privilege.[154]

The new cauldron or vessel will be washed in agua ngongoro, a mix of water and various herbs; the purpose of this is to "cool" the vessel, for the dead are considered "hot".[155] After this, markings known as firmas may be drawn onto the new vessel.[156] Divination will be conducted to check that the nfumbe wishes to enter the nganga, sometimes resulting in negotiations and promises of offerings to secure its assent.[157] When the bones of the nfumbe are being placed inside it, they may be aspirated with white wine and aguardiente and fumigated with cigar smoke.[158] A paper note on which the name of the nfumbe has been written may also be added.[83] During the process of constructing the nganga, an experienced Palo practitioner will divine to ensure that everything is going okay.[159] Corn husk packets called masangó may be added to establish the capacities of that nganga.[160] The creator may also add some of their own blood, providing the new nganga with an infusion of vital force.[161] Within a day of its creation, Palo custom holds that it must be fed with animal blood.[162] Some practitioners will then bury the nganga, either in a cemetery or natural area, before recovering it for use in their rituals.[104]

Maintaining a nganga

The nganga is "fed" with blood from sacrificed male animals.[41] This blood is poured into the nganga,[117] and over time will blacken it.[36] Species used for this purpose include dogs, pigs, goats, and cockerels.[41] Practitioners believe that the blood helps to maintain the nganga's power and vitality and ensures ongoing reciprocity with the practitioner.[75] Human blood is rarely given to the nganga, except sometimes when the latter is being created, so as to animate it, and when a neophyte is being initiated, to help seal the pact between them.[163] It is feared that should the nganga develop a taste for human blood, it will continually demand it, ultimately resulting in the death of its keeper.[107] As well as blood, offerings of food and tobacco are also placed before the nganga;[117] these often include fumigations of cigar smoke and aspirations of cane liquor.[164]

There is a specific etiquette that Palo practitioners follow when engaging with the nganga. They will typically wear white,[165] be barefoot,[166] and have marks on their body, often in cascarilla, designed to keep them "cool" and protect from the tumult of the dead.[167] Practitioners kneel before the ngangas in greeting;[168] they will often greet it with the words "Salaam alaakem, malkem salaam."[169] They may also spray rum onto the nganga with their mouth.[170] In Palo belief, the nganga likes to be addressed in song, and each nganga has particular songs that "belong" to it.[171] A glass of water may be placed nearby, intended to "cool" the presence of the dead;[172] this is also thought to assist spirits of the dead in crossing to the human world.[169] Objects like necklaces may be placed around the nganga so as to be vitalized for use as protective charms.[112] Candles will often be burned while the keeper seeks to work with the vessel.[173] To ensure that a nganga does its keeper's bidding, the latter may sometimes make threats toward it.[174] This "ritual abuse" can extend to insulting the nganga and hitting it with a broom or whip.[175]

When a practitioner dies, their nganga may be dissembled if it is believed that the inhabiting nfumbi refuses to serve anyone else and instead wishes to be set free.[176] The nganga may then be buried beneath a tree in the forest or placed into a river or the sea.[177] Alternatively, Palo teaches that the nganga may wish to take on a new keeper.[177]

Morality, ethics, and gender roles

Palo teaches deference to teachers, elders, and the dead.[50] According to Ochoa, the religion maintains that "speed, strength, and clever decisiveness" are positive traits for practitioners,[178] while also exulting the values of "revolt, risk and change".[179] The religion has not adopted the Christian notion of sin,[180] and does not present a particular model of ethical perfection for its practitioners to strive towards.[181] The focus of the practice is thus not perfection, but power.[10] It has been characterised as a world embracing religion, rather than a world renouncing one.[182]

Both men and women are allowed to practice Palo.[183] While women can hold the most senior positions in the religion,[184] most prayer houses in Havana are run by men,[185] and an attitude of machismo is common among Palo groups.[186] Ochoa thought that Palo could be described as patriarchal,[187] and the scholar of religion Mary Ann Clark encountered many women who thought the community of practitioners to be too masculinist.[188] Many Palo practitioners maintain that women should not be given a nganga while they are still capable of menstruating.[185] Palo teaches that the presence of a menstruating woman near the nganga would weaken it, also maintaining that the nganga's thirst for blood would cause the woman to bleed excessively, causing her harm and potentially even killing her.[189] For this reason, many female practitioners will only receive a nganga decades after their male contemporaries.[185] Gay men are often excluded from Palo,[188] and observers have reported high levels of homophobia within the tradition, in contrast to the large numbers of gay men involved in Santería.[190]

Practices

Palo is an initiatory religion.[9] Its practices are typically secretive, rather than being practised openly.[191] The nganga is central to Palo's ritual practices, representing the "main protagonist" in its ceremonies, trabajos ("works"), and divination.[86] The language used in Palo ceremonies, such as its songs, is often called Palo Kikongo;[192] Ochoa characterised this as a "Creole speech" based on both Kikingo and Spanish.[193] This ritual language has Hispanicized the spelling of many Kikongo words and given them new meanings.[194] Practitioners greet one another with the phrase nsala malekum.[64] They also acknowledge each other with a special handshake in which their right thumbs are locked together and the palms meet.[64]

Praise houses

Palo is organized around autonomous initiatory groups.[195] Each of these groups is called a munanso congo ("Kongo House"),[196] or sometimes the casa templo ("temple house").[197] Ochoa rendered this as "praise house".[196] Their gatherings for ceremonies are supposed to be kept secret.[198] Practitioners sometimes seek to protect the praise house by placing small packets, termed makutos (sing. nkuto), at each corner of the block around the building; these packets contain dirt from four corners and material from the nganga.[64]

Munanso congo form familias de religion (religious families).[9] Each is led by a man or woman regarded as a symbolic parent of their initiates;[9] this senior palero is called a tata nganga ("father nganga"), while the senior palera is a yayi nganga ("mother nganga").[199] This person must have their own nganga and the requisite knowledge of ritual to lead others.[200] This figure is referred to as the padrino ("godfather") or madrina ("godmother") of their initiates;[201] their pupil is the ahijado ("godchild").[202]

Below the tata and yayi of a house are initiates of long-standing, referred to as a padre nganga if male and a madre nganga if female.[98] The initiation of people to this level are rare.[203] At their initiation ceremony to reach the level of padre or madre, a palero/palera will often be given their own nganga cauldron.[204] The tata or yayi may not tell the padre/madre the contents of the new nganga or instructions regarding how to use it, thus ensuring that the teacher maintains control in their relationship with the student.[98]

A tata or yayi may be reluctant to teach their padres and madres too much information about Palo, fearing that if they do so the student will break away from their house and establish an independent one.[98] A padre or madre will not have initiates of their own.[154] A particular padre (but not a madre) might be selected as a special assistant of the tata or yayi; if they serve the former then they are called a bakofula, if they serve the latter they are a mayordomo.[154] The madrinas and padrinas are often considered possessive of their student initiates.[201] Experienced practitioners who run their own praise houses often vie with one another for prospective initiates and will sometimes try to steal members from each other.[205]

An individual seeking initiation into a praise house is usually someone who has previously consulted a palero or palera to request their aid, for instance in the area of health, love, property, or money, or in the fear that they have been bewitched.[206] The Palo practitioner may suggest that the client's misfortunes result from their bad relationship with the spirits of the dead, and that this can be improved by receiving initiation into Palo.[207] New initiates are called ngueyos,[154] a term meaning "child" in the Palo Kikongo language.[208] In the Briyumba and Monte traditions, new initiates are also known as pinos nuevos ("saplings").[208] Ngueyos may attend feasts for the praise house's nganga, to which they are expected to contribute, and may seek advice from it, but they will not receive their own personal nganga nor attend initiation ceremonies for the higher grades.[209] Some practitioners are content to remain at this level and do not pursue further initiation to reach the level of padre or madre.[207]

When the tata or yayi or a house is close to death, they are expected to announce a successor, who will then be ritually accepted as the new tata or yayi by the house members.[210] The new leader may adopt the nganga of their predecessor, resulting in them having multiple nganga to care for.[77] After this leader's death, other senior initiates often have the option of leaving the house and either joining another or establishing their own. This results in some Palo practitioners being members of multiple familias de religion.[210]

Firmas

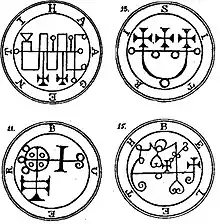

Drawings called firmas, their name derived from the Spanish for "signature", play an important role in Palo ritual.[211] They are alternatively referred to as tratados ("pacts" or "deals").[212] The firmas often incorporate lines, arrows, circles, and crosses.[213] They allow the mpungu to enter the ceremonial space,[64] with a sign corresponding to the mpungu that is being invoked drawn at any given ceremony.[214] As they facilitate contact between the worlds,[215] the firmas are deemed to be caminos ("roads").[216] They also help to establish the will of the living over the dead,[212] directing the action of both the human and spirit participants in a ritual.[217] The firmas are akin to the vèvè employed in Haitian Vodou and the anaforuana used by Abakuá members.[218]

Firmas may derive from the sigils employed in European ceremonial magic traditions.[214] However, some of the designs commonly found in firmas, such as that of the sun circling the Earth and of a horizon line dividing the worlds, are probably borrowed from traditional Kongo cosmology.[219] There are many different designs; some are specific to the mpungu it is intended to invoke, others are specific to a particular munanso congo or to an individual practitioner themselves.[64] As they are deemed very powerful, knowledge of the meanings of the firmas are often kept secret, even from new initiates.[220] Some practitioners have a notebook in which they have drawn the firmas that they use, and from which they may teach others.[221]

Before a ceremony, the firmas are drawn around the room, including on the floor, on the walls, and on ritual objects.[222] They will often be placed at locations suggesting a direction of movement, such as a window or a door.[223] The creation of these drawings are accompanied by chants called mambos.[215] Gunpowder piles at specific points of the firma may then be lit, with the explosion deemed to attract the attentions of the mpungu.[224] Firmas will also be cut into the bodies of new initiates,[220] and drawn onto the nganga as it is being created.[212]

Offerings and animal sacrifice

A range of offerings are given to the nganga, including food, aguardiente, cigars, candles, flowers, and money.[154] Palo maintains that the ngangas seek to feed on blood so as to grow and gain power.[89] Animal sacrifice is thus a key part of Palo ritual,[225] where it is known by the Spanish language term matanza.[226] The choice of animal to be sacrificed depends on the severity of the reason for the offerings. Typically a rooster or two will be killed, but for more important issues a four-legged animal will usually be chosen.[89] The head of the munanso congo is typically responsible for determining what type of sacrifice is appropriate for the situation.[227]

Offerings to the nganga will often be given privately.[228] In Palo custom, it is expected that sacrifices will be made to the nganga on its cumplimiento ("birthday"), the anniversary of its creation.[229] They will also be typically given on the feast day of the Roman Catholic saint who is equated with the Santería oricha that is thought to have most in common with the mpungu manifested in the nganga in question.[89] The mpungu spirit Sarabanda is for instance feasted on June 29, the feast day of Saint Peter (San Pedro), because in Cuban vernacular religion the latter is equated to the oricha Ogún, an entity thought to have similar traits to Sarabanda.[89] A firma will be drawn on the floor where the killing is to take place.[227] There will often be singing, chanting, and sometimes drumming while the sacrificial animal is brought before the nganga;[230] the victim's feet may be washed and it is given water to drink.[154] The animal's throat will then typically be cut,[227] usually by a senior figure in the munanso congo.[154]

The blood of sacrificed animals is deemed very "hot".[231] Different species are thought to have different levels of heat; human blood is thought "hottest", followed by that of turtles, sheep, ducks, and goats, while the blood of other birds, such as chickens and pigeons, is thought "cooler". Animals deemed to have "hotter" blood are usually killed first.[232] The blood may be spilled over the ngangas and over the floor.[172] The animal's severed head may then be placed upon the nganga.[231] Several of the organs will be removed, sautéed, and placed before the nganga, where they will often be left to decompose, producing a strong odor and attracting maggots.[233] Other parts of the body will be taken away and prepared for the consumption of the attendees;[234] attempts are often made to ensure that everyone in attendance at the ritual consumes some of the sacrificed flesh.[235] The sacrifice will often be followed by more generalized celebration involving singing, drumming, and dancing.[227]

Music and dancing

Palo's practitioners put on performances for the nganga involving singing, drumming and dancing.[87] The main style of drum used in Palo is the three-headed tumbadoras; this is distinct from the batá drum used in Santería.[87] These drums are often played in groups of three.[236] As tumbadoras are not always available, Palo's adherents sometimes use plywood boxes as drums.[87] While performing, the drummers may vie against one another to display their skills.[237] Styles of drumming that have been transmitted within Palo include the ritmas congos and influencias bantu.[238]

A typical dance style used in Palo involves the dancer being slightly bent at the waist, swinging their arms and kicking their legs back at the knee.[237] Unlike in Santería, dancers at Palo ceremonies do not proceed in a fixed line during the dance.[237] In Palo, it is believed that during the dancing, one of the dancers may be possessed by the dead.[237]

Initiation and rites of passage

The initiation ceremony into a Palo praise house is known as a rayamiento ("cutting").[239] The ceremony is usually timed to occur on the night of a waxing moon, performed when the moon reaches its fullest light, due to a belief that the moon's potential grows in tandem with that of the dead.[240] It will take place in the el Cuarto de religión ("the room of religion"), sometimes simply known as el Cuarto ("the room").[241] The rayamiento ceremony involves an animal sacrifice; two cockerels are required, although sometimes additional animals will be killed to feed the nganga.[242]

Prior to the initiatory ritual, the initiate will be washed in agua ngongoro, water mixed with various herbs, a procedure called the limpieza; this is done to "cool" them.[243] The initiate will then be brought into the ritual space blindfolded and wearing white;[244] trousers may be rolled up to the knees, a towel over the shoulders, and a bandana on the head. The torso and feet are left unclothed.[245] They may be guided to stand atop a firma drawn on the floor.[246] They make promises to commit to the nganga of the praise house, bringing it offerings at its birthday feasts in return for its protection.[247]

The initiate will then be cut; instruments used have included a razor blade, rooster's spur, or yúa thorn. Cuttings may be made on the chest, shoulders, back, hands, legs, or tongue.[248] Some of the cuts will be straight lines, others may be crosses or more elaborate designs, forming firmas.[249] The cuts are believed to open the initiate up to the spirits of the dead, thus enabling possession.[121] A common belief in Palo is that the dead may possess the initiate at the moment of cutting, and thus it is not thought uncommon if they faint during it.[250] The blood produced is then collected and given to the nganga, something practitioners believe enhances the cauldron's power to either heal or harm the initiate.[251] Strands of the initiate's hair may also be placed in the nganga.[252] Parts of the contents of the nganga may be rubbed into the wounds,[253] sometimes including bone dust scraped from the nfumbe.[254] The initiate's wounds will be packed with candle wax, ntufa, and chamba;[255] the latter is a mix of powdered human bone, rum, chili, and garlic.[256] The cuts sometimes leave scars.[257] Once the cutting has been done, the blindfold will be removed.[258] The new initiate will then head outside to greet the moon and is subsequently expected to visit a nearby cemetery.[259] The suffering endured during the initiation rite is regarded as a test to determine if the neophyte has the qualities that are required of a palero or palera.[256]

Ngueyos must then learn the correct manner in which to approach the nganga and how to perform a sacrifice to it.[208] Students are instructed in Palo through stories, songs, and the recollections of elders; they will also watch their elders and seek to decipher the latter's riddles.[260] A practitioner may later experience a second rayamiento ritual, enabling them to become a full-ranking initiate of the prayer house and thus create their own nganga.[261] At the funeral of a practitioner, a rooster may be sacrificed and its blood poured onto the coffin containing the deceased, thus completing the identification of the dead practitioner with the spirits of the dead.[262] As at the initiation, a firma will often be painted onto the body.[256]

Healing and hexing

Palo's practitioners often claim that their rituals will immediately remedy a problem,[154] and thus clients regularly approach a palero or palera when they want a rapid solution to an issue.[97] The nature of the issue varies; it can involve dealing with state bureaucracy or emigration issues,[263] problems with relationships,[264] or because they fear that they are plagued by a harmful spirit.[265] On occasion, a client may request that the Palo practitioner kill someone for them, using their nganga.[149] The fee paid to a Palo practitioner for their services is called a derecho.[151] Ochoa noted that "common wisdom" in Cuba held that the fees charged by Palo practitioners were less than those charged by Santería practitioners.[151] Indeed, in many cases clients approach Palo practitioners for aid after having already sought help, unsuccessfully, from a Santería initiate.[266]

Practitioners engage in healing through the use of charms, formulas, and spells,[28] often drawing on an advanced knowledge of Cuba's plants and herbs.[267] The first steps that a palero or palera will take to assist someone may be a limpieza or despojo ("clearing") in which the harmful dead are brushed off from an afflicted person.[268] The limpieza will involve a combination of herbs bundled together that are wiped over the body and then burned or buried. Practitioners believe that the effect of these herbs is to "cool" the person to counter the turbulent "heat" of the dead that are around them.[269] The limpieza is also employed in Santería.[269]

Another healing procedure involves creating resguardos, charms that may incorporate tiny pieces of nfumbe, shavings from the palo sticks, earth from a grave and anthill, kimbansa grass, and animal body parts. These will typically be tied into little bundles and inserted into corn husks before being sewn into cloth packets that can be carried by the afflicted person.[270] Songs will often be sung while creating the resguardo, while blood will be offered to vitalise it.[270] The resguardo will often be placed by the nganga for a time to absorb its influence.[116] A Palo practitioner may also turn to the cambio de vida, or life switch, whereby the illness of the terminal patient is transmitted to another, usually a non-human animal but sometimes a doll or a human being, thus saving the client.[271]

A concoction or package made for a client may be called a tratado ("treaty") and contain many of the same elements that go into a nganga.[272] These packages are deemed to gain their power both from the material included within them and the prayers and songs that were performed while they were being created.[273] This may be placed on the nganga to transmit its message to the spirit vessel.[274] Parts of the nganga may also be selected and used to create a guardiero ("guardian"), a vessel designed for a particular purpose; once that purpose is completed, the guardiero may be dissembled and its parts returned to the nganga.[275] If the client's problem persists, the palero/palera will often recommend that the former undergoes an initiation into Palo in order to secure the protection and assistance of a nganga.[154]

Bilongos

In Cuba, it is widely believed that illness may have been caused by a malevolent spirit sent against the sick person by a palero or palera.[276] Some Palo practitioners will identify muertos oscuros (dark dead) entities that have been sent against an afflicted person by enemies, regarding such entities as hiding in plants, materialised in clothes or furniture, concealed in the walls, or taking animal form.[277] If techniques like the limpieza or resguardos fail to deal with a client's problems, a Palo practitioner will often adopt more aggressive methods to assist the afflicted person.[270] They will use divination to identify who it is that has cursed their client;[278] they may then obtain traces of that individual's blood, sweat, or soil that they have walked over, so as to ritually manipulate them.[279]

The Palo counter-attacks are termed bilongos.[280] These will often be concoctions made of various soils and powders;[281] ingredients will often include dried toads, lizards, insects, spiders, human hair, or fish bones.[282] For the bilongo to be effective, practitioners believe, it must be bound in blood to a particular nganga.[138] These will sometimes then be placed inside a jar or bottle.[283] Most bilongo will be buried close to the home of their victim, ideally in the latter's backyard or close to their front door.[284] In Palo belief, the bilongo then draws the nfumbe spirit from out of the keeper's nganga to go and attack the intended victim.[284] The spirit sent to attack may be called a muerto oscuro or enviación.[285] This may be regarded not as the spirit of a dead individual but rather a spirit specifically created for the purpose, a sort of "animate or living automaton".[285] An attack of this nature is called a kindiambazo ("prenda hit") or a cazuelazo ("cauldron blow").[31] This in turn may result in a series of strikes and counter-strikes by different paleros or paleras acting for different clients.[138] In embracing aggressive counter-attacks against perceived malefactors, Palo differs from Santería.[266]

Divination

Palo's practitioners communicate with their spirits via divination.[88] The style of divination employed is determined by the nature of the question that the palero/palera seeks to ask.[219] Two of the divinatory styles employed are the ndungui, which entails divining with pieces of coconut shell, and the chamalongos, which uses mollusc shells. Both of these divinatory styles are also employed, albeit with different names, by adherents of Santería.[88]

Fula is a form of divination using gunpowder. It entails small piles of gunpowder being placed over a board or on the floor. A question is asked and then one of the piles is set alight. If all the piles explode simultaneously, that is taken as an affirmative answer to the question.[286] Another form of divination used in Palo is vititi mensu. This involves a small mirror, which is placed at the opening of an animal horn decorated with beadwork, the mpaka. The mirror is then covered with smoke soot and the palero or palera interprets meanings from the shapes formed by the soot.[287] The mpaka is sometimes called the "eyes of the nganga" and is often kept atop the nganga itself.[256] Both fula and vititi mensu are forms of divination that Palo does not share with Santería.[88]

History

Background

I know of two African religions in the barracoons: the Lucumi and the Congolese... The Congolese used the dead and snakes for their religious rites. They called the dead nkise and the snakes emboba. They prepared big pots called nganga which would walk about and all, and that was where the secret of their spells lay. All the Congolese had these pots for mayombe.

— Esteban Montejo, a slave during the 1860s[288]

After the Spanish Empire conquered Cuba, its Arawak and Ciboney populations dramatically declined.[289] The Spanish then turned to slaves sold at West African ports as a labor source for Cuba's sugar, tobacco, and coffee plantations.[290] Slavery was widespread in West Africa, where prisoners of war and certain criminals were enslaved.[291] Between 702,000 and 1 million enslaved Africans were brought to Cuba,[292] the earliest in 1511,[293] although the majority in the 19th century.[294] In Cuba, slaves were divided into groups termed naciónes (nations), often based on their port of embarkation rather than their own ethno-cultural background.[295]

Palo arises from the Kongo religion of the Bakongo people,[42] drawing various cultural and linguistic elements from the Kingdom of Kongo which covered an area encompassing what is now northern Angola, Cabinda, the Republic of Congo, and parts of both Gabon and the Democratic Republic of Congo.[9] Bakongo slaves formed the largest nación in Cuba between 1760 and 1790, when they comprised over 30 percent of enslaved Africans on the island.[296] Many of these individuals would have brought traditional beliefs and practices with them.[297] Some of the enslaved escaped to form independent colonies, or palenques, where traditional African rituals might continue,[298] while others joined African mutual aid societies, called cabildos or cofradias, some of which were Bakongo-led.[299]

In and around the Kingdom of Kongo, a number of organizations had been active that engaged in religious activities. Lemba was a trading and healing society that emerged on the north bank of the lower Congo River in the mid-17th century and continued operating through to the mid-20th century.[14] Another Kongo society was Nkita, active in the lower Congo Valley in the 19th century.[14] A key part of many of the Kongolese healing traditions were the minkisi, objects containing spirit power,[300] and it is from these that the Palo nganga derives.[66] The minkisi were often baskets or bags, and some of the earliest recorded ngangas were also bags, termed bouma.[63] When the nganga emerged in its current form among Bakongo-descended peoples in Cuba is not known;[301] the sociologist Jualynne E. Dodson suggested a possible link between the iron cauldrons used for nganga and those used to process sugar cane on the island.[301] The nganga would probably have been one of the very few weapons that the enslaved could use against their owners.[97]

In Spanish Cuba, Roman Catholicism was the only religion that could be legally practiced.[302] Cuba's Roman Catholic Church made efforts to convert the enslaved Africans, but the instruction in Roman Catholicism provided to the latter was typically perfunctory and sporadic.[295] The final decades of the 19th century also saw a growing interest in Spiritism, a religion based on the ideas of the French writer Allan Kardec, which in Cuba proved particularly popular among the white peasantry, the Creole class, and the small urban middle class.[303] Spiritism, which in Spanish-language Cuba was often called Espiritismo, also influenced Palo, especially the Palo Mayombe sect.[304]

Formation and early history

Taking earlier influences and fusing them into a new form, Palo developed as a distinct religion in the late 19th or early 20th century.[14] Ochoa described its formation as occurring "in conjunction with, or perhaps in response to", the formation of Santería,[19] a Yoruba-based tradition which emerged in urban parts of western Cuba during the late 19th century.[305] Ochoa noted that "Kongo ideas of the dead" were relegated to "a place of marginality within an emerging Creole cosmos" where Roman Catholicism was dominant but with Yoruba influences also being widespread.[306] He argued that Yoruba ideas of deities could more easily be adapted to Catholicism and thus became dominant over the Kongo ideas.[306] Ochoa believed that Palo arose in Havana.[306] By the turn of the 20th century, it was being transmitted to Oriente in eastern Cuba from the Matanzas area in the west of the island.[297]

At the turn of the 20th century, there were various instances in which European-descended Cubans accused Afro-Cubans of having sacrificed white Christian children to their ngangas.[146] In 1904, a trial was held of Afro-Cubans accused of ritually murdering a toddler named Zoyla Díaz to heal one of their members of sterility; two of them were found guilty and executed.[307] References to the case were passed down in Palo songs down the rest of the century.[308] Police harassment of Palo practitioners continued through the middle of the 20th century.[64]

During the 1940s, various Palo practitioners were studied by the anthropologist Lydia Cabrera.[148] Since this point, many practitioners have read the work of scholars studying their tradition so as to enrich it.[36]

After the Cuban Revolution

The Cuban Revolution of 1959 resulted in the island becoming a Marxist–Leninist state governed by Fidel Castro's Communist Party of Cuba.[309] Committed to state atheism, Castro's government took a negative view of Afro-Cuban religions.[310] However, following the Soviet Union's collapse in the 1990s, Castro's government declared that Cuba was entering a "Special Period" in which new economic measures would be necessary. As part of this, priests of Santería, Ifá, and Palo all took part in government-sponsored tours for foreigners desiring initiation into such traditions.[311] Ochoa noted that Palo "blossomed" amid the liberalising reforms of the mid-1990s.[312]

The decades after the Cuban Revolution saw hundreds of thousands of Cubans emigrate, including Palo practitioners.[314] The 1960s saw Cuban emigres arrive in Venezuela, probably bringing Palo with them, something bolstered by further Cuban arrivals in the early 21st century. In the 2000s, residents reported that many of the graves at Caracas' Cementerio General del Sur had been pried open to have their contents removed for use in Palo ceremonies.[315] Palo also appeared in Mexico. In 1989, the Cuban-American narcotrafficker Adolfo Constanzo and his group were found to have abducted and killed at least 14 people on their ranch outside Matamoros, Tamaulipas in Mexico, with their victims' bones being placed into cauldrons for use in Palo rituals.[316] Constanzo's group had apparently combined Palo with elements from Mexican religions and a statue of the Mexican folk saint Santa Muerte was found on the property.[317] Much media coverage incorrectly labelled these practices "Satanism."[318]

Palo also established a presence in the United States. In 1995, the US Fish and Wildlife Service arrested a Palo Mayombe high priest in Miami, Florida, who was in possession of several human skulls and the remains of exotic animals.[319] In Newark, New Jersey, in 2002, a Palo practitioner was found to have the remains of at least two dead bodies inside pots within the basement, along with items looted from a tomb.[320] A Connecticut Palo priest was arrested in 2015 for allegedly stealing bones from mausoleums in a Worcester, Massachusetts, cemetery.[321] In 2021, two Florida men robbed graves to procure the heads of dead military veterans for Palo ceremonies.[322] In several parts of the U.S., archaeologists and forensic anthropologists have frequently come across remains of ngangas, often referring to them as "Santería skulls", a term that confused Palo with Santería.[323] One example was for instance recovered during the draining of a canal in western Massachusetts in 2012.[324] The American rapper Azealia Banks has also been public about her practice of Palo Mayombe, discussing it and other African diasporic religions on social media from at least 2016.[313]

Denominations

Palo is divided among different denominations or traditions, called ramas,[14] each of which form a ritual lineage.[177] The main four are Briyumba, Kimbisa, Mayombe, and Monte;[14] some practitioners maintain that Mayombe and Monte are the same tradition, whereas elsewhere they have been regarded as separate.[325] Other Palo ramas include Musunde, Quirimbya, and Vrillumba.[28] Many practitioners believe that these names derive from those of different ethnic groups that existed in and around the Kingdom of Kongo.[326] Each of these branches has its own drumming style for use during rituals; the drumming rhythms favored in Mayombe and Briyumba are faster than those in Monte or Kimbisa.[171] In Havana, Palo Monte was one of the two dominant traditions in the late 20th century, resulting in many academic and popular sources using the term "Palo Monte" for the whole religion.[19][lower-alpha 1] Palo Monte means "sticks of the forest."[329]

According to tradition, the Kimbisa sect was founded in the 19th century by Andrés Facundo Cristo de los Dolores Petit, who was highly syncretic in his approach to Palo.[330] Petit merged Palo with elements from Santería, Spiritism, and Roman Catholic mysticism.[331] The tradition is founded on the principles of Christian charity.[332] In Kimbisa temples, it is common to find images of the Virgin Mary, the saints, the crucifix, and an altar to San Luis Beltrán, the patron saint of the tradition.[332] Certain members of other Palo traditions look critically upon Kimbisa, believing that it deviates too far from traditional Kongolese practices.[331]

The Palo nganga has also been incorporated into a Cuban variant of Spiritism, El Espiritismo Cruzao,[333] elsewhere termed Palo Cruzado.[331] In Cuba, the blending of Palo with Spiritist ideas has also been termed Muertería.[334] In rural areas, a tradition called Bembé mixed Central and West African religious traditions.[335]

Demographics

Palo is found all over Cuba,[336] although is particularly strong in the island's eastern provinces.[337] Describing the situation in the 2000s, Ochoa noted that there were "hundreds if not more" Palo praise houses active in Cuba,[50] and in 2015 Kerestetzi commented that the religion was "widespread" on the island.[9] Although emerging from the traditions of Bakongo people, Palo has also been practiced by Afro-Cubans with other ethnic heritages, as well as by Euro-Cubans, criollos, and people living outside Cuba.[338] Ochoa noted that at the close of the 20th century, all different skin tones were represented among Palo's followers in Cuba.[339] Palo has also gained popularity among young people in various urban areas of the U.S.[24]

In Cuba, people are sometimes willing to travel considerable distances to consult with a particular palero or palera about their problems.[340] People first approach the religion because they seek practical help in resolving their problems, not because they wish to worship its deities.[341]

Reception

In Cuban society, Palo is both valued and feared.[97] Ochoa described a "considerable air of dread" surrounding it in Cuban society,[342] while Kerestetzi noted that Cubans usually regarded paleros and paleras as "dangerous and unscrupulous witches."[107] This is often linked to the stereotype that paleros and paleras might kill children for inclusion in their nganga; Ochoa noted that in the 1990s he heard Cuban parents warn children that a "black man with a sack" would carry them off to feed his cauldron.[146] Palo has also become associated with criminal practice, in part due to the illegal nature of obtaining buried human remains;[343] in Cuba, a conviction for desecrating a grave can result in a prison sentence of up to 30 years.[344] The existence of Palo has impacted the burial of various individuals in Cuba. Remigio Herrera, the last surviving African-born babalawo, or priest of Ifá, was for instance buried in an unidentified grave to prevent paleros/paleras digging his corpse up for incorporation in a nganga.[345]

Palo has also been incorporated in popular culture, such as in Leonardo Padura Fuentes' 2001 novel Adiós Hemingway y La cola de la serpiente.[104] By the start of the 21st century, various Cuban artists were incorporating Palo imagery into their work;[40] one example was José Bedia Valdés, who received the nganga spirit Sarabanda at his initiation into Palo.[346] Many artists and graphic artists have adopted firmas without being Palo initiates.[347]

References

Notes

Citations

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 215; Kerestetzi 2015, pp. 145–146; Espírito Santo 2018, p. 68.

- Espírito Santo 2018, p. 83; Kerestetzi 2018, p. xii.

- Bettelheim 2001, p. 36; Palmié 2013, p. 120; Pokines 2015, p. 2.

- Wedel 2004, p. 53; Ochoa 2010, p. 9; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 88.

- Wedel 2004, p. 53; Ochoa 2010, p. 1.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, pp. 89, 95.

- Bettelheim 2001, p. 36.

- Kerestetzi 2015, p. 172.

- Kerestetzi 2015, p. 146.

- Espírito Santo 2018, p. 69.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 200; Espírito Santo 2018, p. 69.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 200.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 12.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 9.

- Mason 2002, p. 88; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 33.

- Wedel 2004, p. 54; Flores-Peña 2005, p. 117; Ochoa 2010, pp. 10, 23; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 89.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 106; Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 196.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 216; Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 196.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 10.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 196.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 245.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 96.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 95.

- Flores-Peña 2005, p. 117.

- Dodson 2008, p. 94; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 89; Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 195.

- Espírito Santo 2018, p. 81.

- Kerestetzi 2015, p. 163.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 89.

- Dodson 2008, p. 95; Ochoa 2010, p. 274.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 274.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 196.

- Bettelheim 2001, p. 36; Dodson 2008, p. 92; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 95; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 160.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 95.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 267.

- Bettelheim 2001, p. 36; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 94.

- Kerestetzi 2015, p. 151.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 200; Winburn, Schoff & Warren 2016, p. 5.

- Kerestetzi 2015, p. 163; Kerestetzi 2018, p. x.

- Dodson 2008, p. 93.

- Bettelheim 2001, p. 37.

- Wedel 2004, p. 54.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 88.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 216; Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 199.

- Palmié 2013, p. 121; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 146.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 277.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 24, 35; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 216.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 21; Palmié 2013, p. 121; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 146.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 45.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 21, 24, 35.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 72.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 31.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 205.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 199; Espírito Santo 2018, p. 81.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 34.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 261.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 40–41.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 43.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 41.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, pp. 203–204, 205.

- Bettelheim 2001, p. 36; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 150.

- Wedel 2004, p. 54; Ochoa 2010, p. 1; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 94; Palmié 2013, p. 21; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 150.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 1.

- Kerestetzi 2015, p. 150.

- Bettelheim 2001, p. 38.

- Kerestetzi 2015, pp. 148, 150.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 131; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 150.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 131.

- Bettelheim 2001, p. 36; Ochoa 2010, p. 140.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 140; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 89; Palmié 2013, p. 121.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 87, 176; Palmié 2013, p. 121; Kerestetzi 2015, pp. 166–167.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 221; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 156.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 88; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 156.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 140.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 89.

- Palmié 2013, p. 121.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 203; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 155.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 88.

- Bettelheim 2001, p. 36; Ochoa 2010, pp. 88–89; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 96; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 154.

- Dodson 2008, pp. 93, 99.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 221; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 96.

- Bettelheim 2001, p. 37; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 89.

- Kerestetzi 2015, p. 151; Winburn, Schoff & Warren 2016, p. 5.

- Kerestetzi 2015, p. 160.

- Wedel 2004, p. 54; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 171; Espírito Santo 2018, p. 69.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 11–12.

- Kerestetzi 2015, p. 152.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 77.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 94.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 185.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 96.

- Kerestetzi 2015, p. 153.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 190.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 241.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 186.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 91.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 9; Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 198.

- Wedel 2004, p. 55.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 73.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 91; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 154.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, pp. 212–213.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, pp. 89–90.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 200; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 164.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 173–174; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 90; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 163.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 90.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 135, 172; Palmié 2013, p. 122.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 135; Palmié 2013, p. 122; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 161.

- Kerestetzi 2015, p. 162.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 135–136; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 90; Palmié 2013, p. 122.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 141.

- Kerestetzi 2015, p. 166.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 198; Kerestetzi 2015, pp. 150–151.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 106.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 173.

- Kerestetzi 2015, pp. 166–167.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 89; Palmié 2013, p. 123; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 169.

- Kerestetzi 2015, p. 170.

- Palmié 2013, p. 122.

- Wedel 2004, p. 54; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 90.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 158.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, pp. 201–202.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 202.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 167; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 90; Palmié 2013, p. 121.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 159.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 161.

- Pokines 2015, p. 6.

- Palmié 2013, pp. 120–121.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 188.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 207.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 96; Winburn, Schoff & Warren 2016, p. 5; Espírito Santo 2018, p. 70.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 197.

- Wedel 2004, p. 55; Palmié 2013, p. 123.

- Palmié 2013, p. 121; Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 207.

- Palmié 2013, p. 122; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 164.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 198; Kerestetzi 2015, pp. 164, 200.

- Wedel 2004, pp. 55–56; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 90; Pokines 2015, p. 2.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 205.

- Bettelheim 2001, p. 43.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 200.

- Bettelheim 2001, p. 43; Pokines 2015, p. 2; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 167.

- Bettelheim 2001, p. 43; Wedel 2004, p. 56.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 204–205; Winburn, Schoff & Warren 2016, p. 5.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 213.

- Wedel 2004, p. 56.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 207, 221.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 226–227, 244.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 208.

- Wedel 2004, p. 56; Ochoa 2010, p. 181.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 207.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 206.

- Kerestetzi 2015, p. 173.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 134.

- Wedel 2004, p. 54; Ochoa 2010, p. 73; Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 198.

- Kerestetzi 2015, p. 156.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 74.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 150–151.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 154; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 157.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 164.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 168.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 170.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 171=172.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 201; Kerestetzi 2015, pp. 161–162.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 134, 183.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, pp. 201, 215; Kerestetzi 2015, pp. 162, 168.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 221.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 227.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 135.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 225, 227.

- Dodson 2008, p. 100; Ochoa 2010, p. 89.

- Dodson 2008, p. 100.

- Dodson 2008, pp. 100–101.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 78.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 107.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 137.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 189–190.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 240.

- Palmié 2013, p. 126; Pokines 2015, p. 6.

- Kerestetzi 2015, p. 171.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 189.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 260.

- Espírito Santo 2018, p. 68.

- Espírito Santo 2018, pp. 68–69.

- Espírito Santo 2018, p. 76.

- Clark 2005, p. 63; Espírito Santo 2018, p. 69.

- Dodson 2008, p. 103.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 76.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 270.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 76, 140.

- Clark 2005, p. 63.

- Wedel 2004, p. 54; Ochoa 2010, p. 76.

- Clark 2005, p. 63; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 270.

- Wedel 2004, p. 54; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 94.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 67.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 266.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 273.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 58; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 146.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 9, 266.

- Bettelheim 2001, p. 38; Ochoa 2010, p. 271.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 98.

- Dodson 2008, p. 98; Ochoa 2010, p. 72; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 94.

- Dodson 2008, p. 98.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 84.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 12; Espírito Santo 2018, p. 77.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 133.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 73, 133.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 146.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 74; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 154.

- Kerestetzi 2015, p. 154.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 75.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 75; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 154.

- Dodson 2008, p. 97.

- Bettelheim 2001, p. 38; Ochoa 2010, p. 154.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 154.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 157; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 157.

- Kerestetzi 2015, p. 157.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 93.

- Bettelheim 2001, p. 38; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 159.

- Kerestetzi 2015, pp. 157, 159.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 154; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, pp. 92–93.

- Bettelheim 2001, p. 39.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 155.

- Bettelheim 2001, p. 46.

- Bettelheim 2001, p. 38; Ochoa 2010, p. 155.

- Kerestetzi 2015, p. 159.

- Bettelheim 2001, pp. 38–39; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 159.

- Dodson 2008, p. 96; Winburn, Schoff & Warren 2016, p. 6.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 97.

- Dodson 2008, p. 101.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 118.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 185; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 171.

- Dodson 2008, p. 101; Ochoa 2010, p. 74.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 108.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 119.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 184; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 169.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 108–109.

- Dodson 2008, pp. 101–102.

- Dodson 2008, p. 88.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 79.

- Hagedorn 2001, p. 47.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 74, 97; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 95; Palmié 2013, p. 123.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 99.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 101.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 109.

- Bettelheim 2001, p. 38; Ochoa 2010, pp. 111–112, 150.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 97, 111.

- Bettelheim 2001, p. 40.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 112.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 113–114.

- Bettelheim 2001, pp. 40, 41; Ochoa 2010, pp. 116–117, 122; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 95; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 168.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 122, 155.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 120.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 114, 123; Kerestetzi 2015, pp. 168–169.

- Bettelheim 2001, p. 41.

- Palmié 2013, p. 123.

- Bettelheim 2001, p. 40; Espírito Santo 2018, p. 81.

- Bettelheim 2001, pp. 40–41; Ochoa 2010, p. 124.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 216.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 122–123; Kerestetzi 2015, p. 169.

- Bettelheim 2001, p. 41; Ochoa 2010, p. 127.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 128.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 13, 75–76.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 206.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, pp. 204–205.

- Wedel 2004, p. 46.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 223.

- Espírito Santo 2018, p. 75.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 193.

- Wedel 2004, pp. 42, 45, 55.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 191–192.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 192.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 194.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 213; Espírito Santo 2018, p. 82.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 203; Espírito Santo 2018, p. 81.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 212.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 203.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, pp. 209–210.

- Wedel 2004, p. 48.

- Espírito Santo 2018, p. 71.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 194–195.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 213.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 196; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 94.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 196–197.

- Wedel 2004, p. 55; Ochoa 2010, p. 197.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 198.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 199.

- Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 210.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 256; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, pp. 94–95.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 95; Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 216.

- Brandon 1993, p. 169.

- Brandon 1993, p. 40; Hagedorn 2001, p. 184.

- Brandon 1993, p. 44; Hagedorn 2001, p. 184.

- Brandon 1993, p. 19.

- Brandon 1993, p. 43.

- Hagedorn 2001, p. 184.

- Brandon 1993, p. 43; Hagedorn 2000, p. 100; Hagedorn 2001, p. 75.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 34.

- Brandon 1993, p. 57.

- Dodson 2008, p. 84.

- Dodson 2008, pp. 86–87.

- Dodson 2008, p. 90; Ochoa 2010, p. 9.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 132.

- Dodson 2008, p. 89.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 35.

- Brandon 1993, pp. 86–87; Sandoval 1979, p. 141.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 209.

- Clark 2001, p. 23; Wirtz 2007, p. 30.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 217.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 208–210.

- Ochoa 2010, pp. 210–212.

- Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 83.

- Hagedorn 2001, p. 197; Ayorinde 2007, p. 156.

- Hagedorn 2001, p. 8.

- Ochoa 2010, p. 183.

- Pérez 2021, p. 520.