Deendayal Upadhyaya

Deendayal Upadhyaya (25 September 1916 – 11 February 1968) was an Indian politician, proponent of integral humanism ideology and leader of the political party Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS), the forerunner of Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).[2] Upadhyaya started the monthly publication Rashtra Dharma, broadly meaning 'National Faith', in the 1940s to spread the ideals of Hindutva revival.[3] Upadhyaya is known for drafting Jan Sangh's official political doctrine, Integral humanism,[1] by including some cultural-nationalism values and his agreement with several Gandhian socialist principles such as sarvodaya (progress of all) and swadeshi (self-sufficiency).[4]

Deendayal Upadhyaya | |

|---|---|

Bust of Upadhyaya | |

| 10th President of Bharatiya Jana Sangh | |

| In office December 1967 – February 1968 | |

| Preceded by | Balraj Madhok |

| Succeeded by | Atal Bihari Vajpayee |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 25 September 1916 Nagla Chandraban, Mathura, United Provinces, British India (present-day Deendayal Dham, Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India) |

| Died | 11 February 1968 (aged 51) Mughalsarai, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| Political party | Bharatiya Jana Sangh |

| Alma mater | Sanatan Dharma College, Kanpur, Agra University (BA) |

| Known for | Integral Humanism[1] |

Early life

Upadhyaya was born in 1916 in the village of Nagla Chandraban, now called Deendayal Dham, near the town of Farah in Mathura District, 26 km (16 mi) from Mathura in a Brahmin family.[5][6] His father, Bhagwati Prasad Upadhyaya, was an astrologer and his mother, Rampyari Upadhyaya, was a homemaker and observant Hindu. Both his parents died when he was eight years old and he was brought up by his maternal uncle. His education, under the guardianship of his maternal uncle and aunt, saw him attend high school in Sikar. The Maharaja of Sikar gave him a gold medal, Rs 250 to buy books and a monthly scholarship of Rs 10.[5] and did his Intermediate in Pilani, Rajasthan, (Now Birla School, Pilani).[7][8] He took a BA degree at the Sanatan Dharma College, Kanpur. In 1939 he moved over to Agra and joined St. John's College, Agra to pursue a master's degree in English literature but could not continue his studies.[9] He did not take up his MA exams due to some family and financial issues. [10] He was came to be known as Panditji for appearing in the civil services examination, wearing the traditional Indian dhoti-kurta and cap.[11]

Career

Upadhyaya had come into contact with the RSS through a classmate, Baluji Mahashabde, while studying at Sanatan Dharma College in 1937. He met the founder of the RSS, K. B. Hedgewar, who engaged with him in an intellectual discussion at one of the shakhas. Sunder Singh Bhandari was also one of his classmates at Kanpur. He started full-time work in the RSS from 1942. He had attended the 40-day summer vacation RSS camp at Nagpur where he underwent training in Sangh Education. After completing second-year training in the RSS Education Wing, Upadhyaya became a lifelong pracharak of the RSS. He worked as the pracharak for the Lakhimpur district and, from 1955, as the joint Prant Pracharak (regional organiser) for Uttar Pradesh. He was regarded as an ideal swayamsevak of the RSS essentially because ‘his discourse reflected the pure thought-current of the Sangh’.[12]

Upadhyaya started the monthly Rashtra Dharma publication from Lucknow in the 1940s, using it to spread Hindutva ideology. Later he started the weekly Panchjanya and the daily Swadesh.[13]

In 1951, when Syama Prasad Mookerjee founded the BJS, Deendayal was seconded to the party by the RSS, tasked with moulding it into a genuine member of the Sangh Parivar. He was appointed as General Secretary of its Uttar Pradesh branch, and later the all-India general secretary. For 15 years, he remained the outfit's general secretary. He also contested by-poll for the Lok Sabha seat of Jaunpur from Uttar Pradesh in 1963 bi election when Jansangh MP Bramh Jeet Singh died, but failed to attract significant political traction and did not get elected.

In the 1967 general elections, the Jana Sangh got 35 seats and became the 3rd largest party in the Lok Sabha. The Jan Sangh also went onto be a part of the Samyukta Vidhayak Dal, an experiment of having non-Congress opposition parties as a coalition to form governments in multiple states This brought the right and the left of the Indian political spectrum on one single platform.[14] He became president of the Jana Sangh in December 1967 in the Calicut session of the party. His presidential speech in that session focused on multiple aspects right from the formation of coalition government to language.[15] No major events happened in the party during his tenure as the president that ended in 2 months in February 1968 due to his untimely death.

Upadhyaya edited Panchjanya (weekly) and Swadesh (daily) from Lucknow. In Hindi, he wrote a drama on Chandragupta Maurya, and later wrote a biography of Shankaracharya. He translated a Marathi biography of Hedgewar.

In December 1967, Upadhyaya was elected president of the BJS.[16]

Philosophy

Integral humanism was a set of concepts drafted by Upadhyaya as a political program and adopted in 1965 as the official doctrine of the Jan Sangh.[17]

Death

On February 10, 1968, Upadhyaya boarded a late-night train from Lucknow to Patna, which made several stops along the way. Upadhyaya was confirmed to have been seen alive at Jaunpur, shortly after midnight. The train briefly stopped at Varanasi around 01:40 am before proceeding on to Mughalsarai; on arrival at 2:10 am, Upadhyaya was not aboard.[16][18] At approximately 2:20 am, his body was located outside the Mughalsarai train station, nearly 750 feet from the platform. A five-rupee note was in his hand.[16]

The Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) investigation team determined that Upadhyaya had been pushed out of the coach by robbers just before the train entered Mughalsarai station.[18] A passenger travelling in the cabin adjoining Upadhyaya's reported seeing a man removing files and bedding from it. This man was later identified as Bharat Lal.[16] The CBI arrested Lal and his associate Ram Awadh and charged the pair with murder and theft.[16] According to the CBI, the men stated that Upadhyaya had caught them attempting to steal his bag and threatened to call the police, so they pushed him from the train.[18] The men were acquitted of the murder charges. Lal was convicted of the theft, but appealed to the Allahabad High Court.[16][18]

The murder remains officially unresolved. Many people believed the murder to be politically motivated, and felt that the CBI had not handled the case correctly.[16][19][20] Following the acquittals, over 70 MPs demanded a commission of inquiry.[16] The Government of India appointed Justice Y.V. Chandrachud of the Bombay High Court to lead a single-person inquiry into the facts of the case.[16] His findings were published in 1970.[20] According to Chandrachud, the CBI's investigation had produced an accurate picture of the death as a spontaneous incident resulting from an interrupted theft. He found no evidence of political motivation.[16]

In 2017, Upadhyaya's niece and several politicians demanded a fresh probe in his murder.[21]

Legacy

Since 2016 the BJP government under Prime Minister Narendra Modi named several public institutions after him.[22][23] In Delhi, a road/marg has been named after Upadhyaya. In August 2017, the BJP state government in UP proposed renaming of Mughalsarai station in honour of Upadhyaya as his dead body was found near it.[22] Opposition parties protested this move in the Parliament of India. The Samajwadi Party protested with a statement that the station was being renamed after someone "who had made no contribution to the freedom struggle".[24] The Deen Dayal Research Institute deals with queries on Upadhyaya and his works.[25]

In 2018 a newly constructed cable-stayed bridge in Surat was named Pandit Dindayal Upadhyay Bridge in honor of him.[26]

On 16 February 2020 in Varanasi, Narendra Modi opened the Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya Memorial Centre and unveiled a 63-foot statue of Upadhyaya, his tallest statue in the country.[27]

Stamp issued in 1978

Stamp issued in 1978 Stamp issued in 2015

Stamp issued in 2015 Stamp issued in 2016

Stamp issued in 2016 Stamp issued in 2018

Stamp issued in 2018

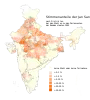

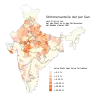

Footprint of Bharatiya Jana Sangh in 1952

Footprint of Bharatiya Jana Sangh in 1952 Footprint of Bharatiya Jana Sangh in 1957

Footprint of Bharatiya Jana Sangh in 1957 Footprint of Bharatiya Jana Sangh in 1962

Footprint of Bharatiya Jana Sangh in 1962 Footprint of Bharatiya Jana Sangh in 1967

Footprint of Bharatiya Jana Sangh in 1967

See also

References

- Hansen, Thomas (1999). The Saffron Wave: Democracy and Hindu nationalism in modern India. NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 89. ISBN 9780691006710. Archived from the original on 4 September 2009.

- Dutta, Prabhash K. (21 September 2017). "Who was Deendayal Upadhyay, the man PM Narendra Modi often refers to in his speeches?". India Today. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- "Points about Deendayal Upadhyay". IndiaToday. 25 September 2018. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- Gosling, David (2001). Religion and ecology in India and southeast Asia. London New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24030-1.

- Singh, Manoj. Deendayal Upadhyaya (First ed.). Preface: Lakshay Books. p. 7. ISBN 9788188992379.

- Sahasrabuddhe, Vinay (24 September 2016). "With Focus on Vikas, Deendayal Upadhyaya Went Beyond Public vs Private". BloombergQuint. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- Prabhash K Dutta (21 September 2017). "Who was Deendayal Upadhyay, the man PM Narendra Modi often refers to in his speeches?". India Today. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- "Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya". rajasthan.bjym.org. Archived from the original on 7 June 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- "End of an Era". deendayalupadhyay.org. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- Singh, Manoj. Deendayal Upadhyaya (First ed.). Biography: Lakshay Books. p. 9. ISBN 9788188992379.

- Anand, Arun (25 September 2020). "Who killed Deendayal Upadhyaya? It's a 50-year-old question". ThePrint. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2007). Hindu Nationalism – A Reader. Princeton University Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-691-13097-2.

- "Deendayal Upadhyaya". Bharatiya Janata party. Archived from the original on 21 September 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- "Deen Dayal Upadhyaya, a swayamsevak, was pitchforked to lead Jana Sangh at a critical juncture in party's history", indianexpress.com, indianexpress.com, 25 September 2019, archived from the original on 12 April 2020

- Trivedi, Preeti (December 2017). Architect of A Philosophy. pustak.org. pp. 308–312. ISBN 978-1-61301-638-1.

- Noorani, A.G. (2012). Islam, South Asia and the Cold War. Tulika Books. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- Hansen, Thomas (1999). The Saffron Wave: Democracy and Hindu nationalism in modern India. NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 84. ISBN 9780691006710. Archived from the original on 4 September 2009. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Pandey, Deepak K. (25 May 2015). "Probe murder of Deendayal Upadhyaya afresh: Swamy". The Hindu. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- "Unsolved midnight murder mystery of Deendayal Upadhyaya at Mughalsarai Junction". www.timesnownews.com. 5 June 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- Husain, Yusra (11 February 2018). "Blood on the tracks: A journey that led to a fatal destination". The Times of India. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- "Cong asks for fresh probe into Deendayal Upadhyay's death". DNA India. Press Trust of India. 11 August 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- Chatterjee, Manini (25 September 2017). "Manufacturing an icon – The Deendayal Upadhyaya, one of the university is also name in Sikar. blitzkrieg". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- Bindu Shajan Perappadan (19 June 2014). "Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Hospital to become a medical college-cum-hospital". Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- "SP, BSP oppose renaming of Mughalsarai railway station". LiveMint. PTI. 4 August 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- Kang, Bhavdeep (6 October 2014) Who is this man who features in every Modi speech? News.Yahoo.com

- "Pandit Dindayal Upadhya Bridge". Surat Municipal Corporation. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- "PM Modi Launches, lays foundation stone of 50 projects worth Rs 1,254 crore in Varanasi". TribuneIndia. 16 February 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

External links

- A short glimpse at the life and times of Pt. Deendayal Upadhyaya Archived 20 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine at Nehru Memorial