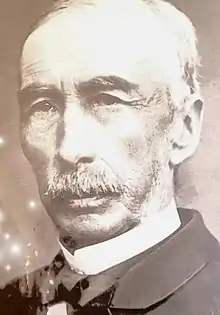

Pantaleón Dalence

Pantaleón Dalence Jiménez (27 July 1815 – 22 September 1892) was a Bolivian jurist and Minister of Finance during the presidencies of Adolfo Ballivián and Tomás Frías. He is considered the "Father of Bolivian Justice".[1] He served as President of the Supreme Court between 1871 and 1889 on various occasions.

Pantaleón Dalence | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister of Finance | |

| In office 27 September 1873 – 11 January 1875 | |

| President | Adolfo Ballivián Tomás Frías |

| Preceded by | Mariano Baptista |

| Succeeded by | Daniel Calvo |

| Personal details | |

| Born | July 27, 1815 Oruro, Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata (now Bolivia) |

| Died | September 22, 1892 Sucre, Bolivia |

| Spouse | Manuela Bellot |

| Children | Zenón, José María, Pantaleón, Etelvina, and Teresa |

| Alma mater | University of San Francisco Xavier |

| Occupation | Jurist |

Early life

Pantaleón Dalence Jiménez, was born on July 27, 1815, in the city of Oruro, the son of José María Dalence, considered one of the founding fathers of Bolivia. Studying at the University of San Francisco Xavier, Dalence graduated as a lawyer in 1836. His primary studies were conducted under the direction of Simón Rodríguez, who was the mentor of Simón Bolívar. He would learn much from his father, who was a judge and served as a magistrate in the Supreme Court of Bolivia.

Minister of Finance

In 1873, Adolfo Ballivián appointed Dalence as his Minister of Finance. Even after Ballivián's death, Dalence remained in charge of the ministry. During his tenure, Dalence played a role in the memorable and important Nrional Assembly of 1874. As per the Constitution, legislative elections were to be held that year. In La Paz, out of the four possible deputies, not a single ally of the current administration had won. In fact, all the winners belonged to the opposition and included Casimiro Corral. In Cochabamba, three out of four winners were from the opposition, including General Quintín Quevedo. The general opposition against President Tomás Frías began to rise, with many newspapers throughout the country publishing anti-government propaganda. Nonetheless, Frías and his government called the Assembly to meet, eager to discuss issues concerning the national budget, with the President determined to carry out a General Audit in said upcoming session. The discussion about the economic condition of the country began with the burdensome Valdeavellano loan, an agreement made during the administration of Agustín Morales. 500,000 pesos were borrowed, with an interest rate of 8% per annum, at an initial rate of 5%. The loan could only be cancelled six months after the initial agreement and was renewable for three months after its termination, considering that the lender be paid with the same percentage of interest for every semester thereafter. By 1874, the debt had increased to 673,000 pesos, requiring 90,000 pesos annually at an interest rate of 18% per annum, causing a massive burden on the national economy. On July 24, the Assembly decided to pay the entirety of the debt.[2]

On August 10, the Assembly met to discuss two proposals which the President wanted to introduce for debate. After his introductory speech, Frías presented them. In summary, his proposals were the introduction of an organic law of military conscription and a municipal reform. His proposal for military conscription was based on his belief that Bolivia had found itself in constant anarchy since its birth because of the army; that because the army had not been constitutionally conscripted, anarchic and revolutionary ideals arbitrarily abounded in the army. He added that the arbitrary recruitment of soldiers, a practice that had dominated the country since independence, had been unconstitutional and therefore had to be amended. After all, it was the Bolivian Army that was in charge of defending the laws and the constitution which dictated them; that was their purpose, defend democracy and liberty, not work for their own personal gain. Regarding municipalities, Frías believed that each municipality had to submit their deliberations which were to be examined and discussed by the National Assembly. Without much debate, the Assembly agreed with this proposal.[3][4]

The continued resistance from the municipalities was deemed unconstitutional and resulted in a council of ministers having to officially approve the law and enforce it. As a result of this bureaucratic insubordination, Frías ordered the presentation of memorandums from each ministry concerning the year 1873. Dalence presented that the government had, in the previous year, a total income of 3,447,785.88 pesos; total expenditures of 3,660,679.69 pesos; and a déficit of 212,993.81 pesos. The Ministry of Public Instruction presented, in its memorandum to the Assembly, evidence of strict its adherence to the Law of Free Teaching, enacted on November 22, 1872. This law stipulated the following principles: the promotion public instruction; the practice free teaching at the municipal level; and the acknowledgement of instructors as the representatives of their communities. As for the Ministry of War, their memorandum stated the continued support of the army to the current administration. It also included a count of active military personnel, declaring the number to be 1,789 men. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs presented that an agreement had been finally reached with Chile regarding the border conflict; that Chile and Bolivia had finally reached the conclusion of the unfinished treaty signed in 1866 under Mariano Melgarejo.

Finally, the time to discuss the most important concern in the minds of the anxious deputies had come. The questioned legality of the Frías administration was put to discussion, and it was agreed by the majority, and a revision committee, that the President was indeed serving constitutionally. Even some of his own stuff detractors, such as General Quevedo and his party, accepted the legality of Frías' accession; however, Corral and his partisans vehemently rejected it. The corralistas argued that, Frías, having renounced the Presidency in 1873, had also renounced the Presidency of the Council of State and, thus, could not possibly be considered the legal successor of the deceased Ballivián.[5]

On September 7, the Assembly discussed the municipalities crisis which emerged from the law of March 2, placing municipalities under the scrutiny of the government. This had caused the insubordination of several municipal councils and had led to resistance. A passionate and lengthy discussion ensued, ending indecisively and failing to solve an issue that had caused the insubordination of several municipalities.[6]

Death and legacy

Dalence died on September 22, 1892, in the city of Sucre. His face is seen in the 20 boliviano bill.[7]

References

- "Billete de 20 bolivianos, biografía de Pantaleón Dalence, Banco Central de Bolivia".

- Dalence, Pantaleon (1878). La hacienda de Bolivia sus obligaciones y sus recursos [by P. Dalence] (in Spanish). pp. 5–6.

- Bolivia (1874). Anuario de Leyes Y Disposiciones Supremas (in Spanish). pp. 236–237.

- Paz, Luis (1912). Constitución política de la República de Bolivia, su texto, su historia comentario (in Spanish). M. Pizarro. p. 458.

- G, Medina Guerrero Medina (1991). Bolivia y sus presidentes: biografías (in Spanish). Producciones Hepta. p. 102.

- Sanjinés, Jenaro (1902). Apuntes para la historia de Bolivia bajo las administraciones de don Adolfo Ballivián I [i.e. y] don Tomás Frías (in Spanish). Impr. Bolivar de M. Pizarro. pp. 119–161.

- "Rinden homenaje a jurisconsulto Pantaleón Dalence". ANF. 1995.