Chessboard paradox

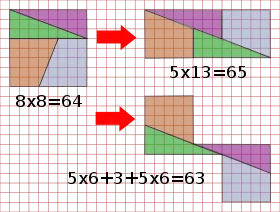

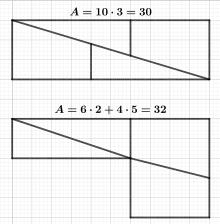

The chessboard paradox[1][2] or paradox of Loyd and Schlömilch[3] is a falsidical paradox based on an optical illusion. A chessboard or a square with a side length of 8 units is cut into four pieces. Those four pieces are used to form a rectangle with side lengths of 13 and 5 units. Hence the combined area of all four pieces is 64 area units in the square but 65 area units in the rectangle, this seeming contradiction is due an optical illusion as the four pieces don't fit exactly in the rectangle, but leave a small barely visible gap around the rectangle's diagonal. The paradox is sometimes attributed to the American puzzle inventor Sam Loyd (1841–1911) and the German mathematician Oskar Schlömilch (1832–1901)

Analysis

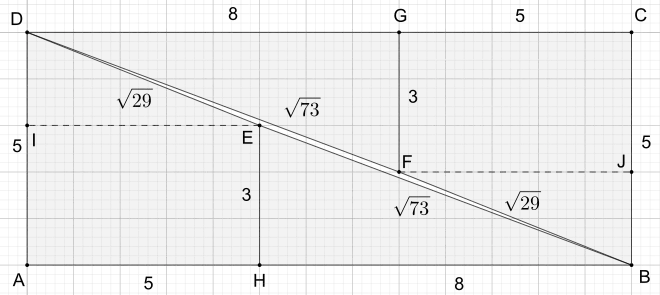

Upon close inspection one can see that the four pieces don't fit quite together but leave a small barely visible gap around the diagonal of the rectangle. This gap has the shape of a parallelogram, which can be checked by showing that the opposing angles are of equal size.[4]

An exact fit of the four pieces along the rectangle's requires the parallelogram to collapse into a line segments, which means its need to have the following sizes:

Since the actual angles deviate only slightly from those values, it creates the optical illusion of the parallelogram being just a line segment and the pieces fitting exactly.[4] Alternatively one can verify the parallelism by placing the reactangle in a coordinate system and compare slopes or vector representation of the sides.

The side length and diagonals of the parallelogram are:

Using Heron's formula one can compute the area of half of the parallelogram (). The halved circumference is

which yields the area of the whole parallelogram:

So the area of the gap accounts exactly for the additional area of the rectangle.

Generalization

the triangles are nearly similar

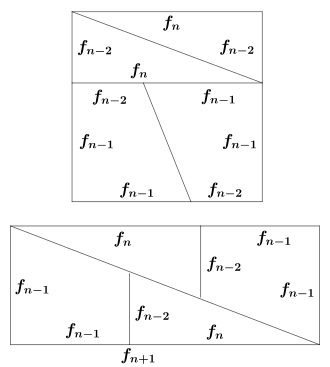

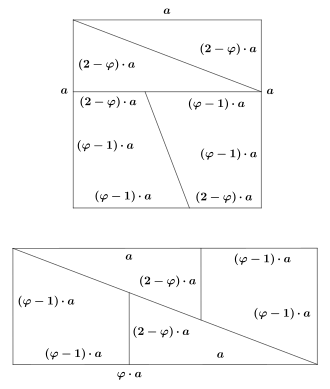

The line segments occurring in the drawing of the last chapters are of length 2, 3, 5, 8 and 13. These are all sequential Fibonacci numbers, suggesting a generalization of the dissection scheme based on Fibonacci numbers. The properties of the Fibonacci numbers also provide some deeper insight, why the optical illusion works so well. A square whose side length is the Fibonacci number can be dissected using line segments of lengths in the same way the chessboard was dissected using line segments of lengths 8, 5, 3 (see graphic).[4]

Cassini's identity states:[4]

From this it is immediately clear that the difference in area between square and rectangle must always be 1 area unit, in particular for the original chessboard paradox one has:

Note than for an uneven index the area of the square is not smaller by one area unit but larger. In this case the four pieces don't create a small gap when assembled into the rectangle, but they overlap slightly instead. Since the difference in area is always 1 area unit the optical illusion can be improved using larger Fibonacci numbers allowing gap's percentage of the rectangle area to become arbitrarily small and hence for practical purposes invisible.

Since the ratio of neighboring Fibonacci numbers converges rather quickly against the golden ratio , the following ratios converge quickly as well:

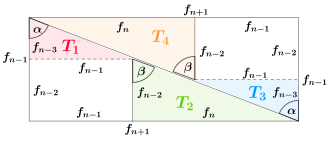

For the four cut-outs of the square to fit together exactly to form a rectangle the small parallelogram needs to collapse into a line segment being the diagonal of the rectangle. In this case the following holds for angles in the rectangle due to being corresponding angles of parallels:

- , , ,

As a consequence the following right triangles , , and must be similar and the ratio of their legs must be the same.

Due to the quick convergence stated above the according ratios of Fibonacci numbers in the assembled rectangle are almost the same:[4]

Hence they almost fit together exactly, this creates the optical illusion.

One can also look at the angles of the parallelogram as in the original chessboard analysis. For those angles the following formulas can derived:[4]

Hence the angles converge quickly towards the values needed for an exact fit.

It is however possible to use the dissection scheme without a creating an area mismatch, that is the four cut-outs will assemble exactly into an rectangle of the same area as the square. Instead of using Fibonacci numbers one bases the dissection directly on the golden ratio itself (see drawing). For a square of side length this yields for the area of the rectangle

since is a property of the golden ratio.[5]

History

Hooper's paradox can be seen as a precursor to chess paradox. In it you have the same figure of four pieces assembled into a rectangle, however the dissected shape from which the four pieces originate is not a square yet nor are the involved line segments based on Fibonacci numbers. Hooper published the paradox now named after him under the name The geometric money in his book Rational Recreations. It was however not his invention since his book was essentially a translation of the Nouvelles récréations physiques et mathétiques by Edmé Gilles Guyot (1706–1786), which had been published in France in 1769.'[1]

The first known publication of the actual chess paradox is due to the German mathematician Oskar Schlömilch. He published in 1868 it under title Ein geometrisches Paradoxon ("a geometrical Paradox") in the German science journal Zeitschrift für Mathematik und Physik. In the same journal Victor Schlegel published in 1879 the article Verallgemeinerung eines geometrischen Paradoxons ("a generalisation of a geometrical paradox"), in which he generalised the construction and pointed out the connection to the Fibonacci numbers. The chessboard paradox was also a favorite of the British mathematician and author Lewis Carroll, who worked on generalization as well but without publishing it. This was later discovered in his notes after his death. The American puzzle inventor Sam Loyd claimed to have presented the chessboard paradox at the world chess congress in 1858 and it was later contained in Sam Loyd's Cyclopedia of 5,000 Puzzles, Tricks and Conundrums (1914), which was posthumously published by his son of the same name. The son stated that the assembly of the four pieces into a figure of 63 area units (see graphic at the top) was his idea. It was however already published in 1901 in the article Some postcard puzzles by Walter Dexter.'[1][6]

See also

References

- Greg N. Frederickson: Dissections: Plane and Fancy. Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 9780521525824, chapter 23, pp. 268–277 in particular pp. 271–274 (online update for chapter 23)

- Colin Foster: "Slippery Slopes". In: Mathematics in School, vol. 34, no. 3 (May, 2005), pp. 33–34 (JSTOR)

- Franz Lemmermeyer: Mathematik à la Carte: Elementargeometrie an Quadratwurzeln mit einigen geschichtlichen Bemerkungen. Springer 2014, ISBN 9783662452707, pp. 95–96 (German)

- Thomas Koshy: Fibonacci and Lucas Numbers with Applications. Wiley, 2001, ISBN 9781118031315, pp. 74, 100–108

- Albrecht Beutelspacher, Bernhard Petri: Der Goldene Schnitt. Spektrum, Heidelberg/Berlin/Oxford 1996. ISBN 3-86025-404-9, pp. 91–93 (German)

- Martin Gardner: Mathematics, Magic and Mystery. Courier (Dover), 1956, ISBN 9780486203355, pp. 129–155

Further reading

- Jean-Paul Delahaye: Au pays des paradoxes. Humensis, 2014, ISBN 9782842451363 (French)

- Miodrag Petkovic: Famous Puzzles of Great Mathematicians. AMS, 2009, ISBN 9780821848142, pp. 14, 30–31

- A. F. Horadam: "Fibonacci Sequences and a Geometrical Paradox". In: Mathematics Magazine, vol. 35, no. 1 (Jan., 1962), pp. 1–11 (JSTOR)

- David Singmaster: "Vanishing Area Puzzles". In: Recreational Mathematics Magazine, no. 1, March 2014

- John F. Lamb Jr.: "The Rug-cutting Puzzle". In: The Mathematics Teacher, Band 80, Nr. 1 (Januar 1987), pp. 12–14 (JSTOR)

- Warren Weaver: "Lewis Carroll and a Geometrical Paradox". In: The American Mathematical Monthly, vol. 45, no. 4 (Apr., 1938), pp. 234–236 (JSTOR)

- Oskar Schlömilch: "Ein geometrisches Paradoxon". In: Zeitschrift für Mathematik und Physik, vol. 13, 1868, p. 162 (German)

- Victor Schlegel: "Verallgemeinerung eines geometrischen Paradoxons". In: Zeitschrift für Mathematik und Physik, vol. 24, 1879, pp. 123–128 (German)