Disability sport classification

Disability sports classification is a system that allows for fair competition between people with different types of disabilities.

Historically, the process has been overseen by 2 groups: specific disability type sport organizations that cover multiple sports, and specific sport organizations that cover multiple disability types including amputations, cerebral palsy, deafness, intellectual impairments, les autres and short stature, vision impairments, spinal cord injuries, and other disabilities not covered by these groups. Within specific disability types, some of the major organizations have been: CPISRA for cerebral palsy and head injuries, ISMWSF for spinal cord injuries, ISOD for orthopaedic conditions and amputees, INAS for people with intellectual disabilities, and IBSA for blind and vision impaired athletes.

Amputee sports classification is a disability specific sport classification used for disability sports to facilitate fair competition among people with different types of amputations. This classification was set up by International Sports Organization for the Disabled (ISOD), and is currently managed by IWAS who ISOD merged with in 2005. Several sports have sport specific governing bodies managing classification for amputee sportspeople. The classes for ISOD's amputee sports classification system are A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, A6, A7, A8 and A9. The first four are for people with lower limb amputations. A5 through A8 are for people with upper limb amputations.

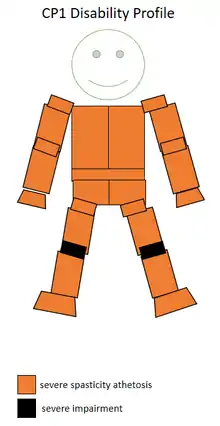

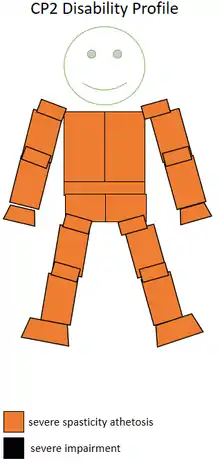

Cerebral palsy sport classification is a classification system used by sports that include people with cerebral palsy (CP) with different degrees of severity to compete fairly against each other and against others with different types of disabilities. In general, Cerebral Palsy-International Sports and Recreation Association (CP-ISRA) serves as the body in charge of classification for cerebral palsy sport, though some sports have their own classification systems which apply to CP sportspeople. The classification system developed by the CP-ISRA includes eight classes: CP1, CP2, CP3, CP4, CP5, CP6, CP7 and CP8. These classes can be generally grouped into upper wheelchair, wheelchair and ambulatory classes. CP1 is the class for upper wheelchair, while CP2, CP3 and CP4 are general wheelchair classes. CP5, CP6, CP7 and CP8 are ambulatory classes.

The Les Autres class of disabilities generally covers two classes. These are people with short stature and people with impaired passive range of movement. The latter is sometimes referred to as PROM. There are a number of sports open to people who fit into Les Autres classes, though their eligibility often depends on if they have short stature or PROM. Historically, disability sports classification has not been open specifically to people with transplants, diabetics and epileptics. This is because disabilities need to be permanent in nature.

Classification for disability sports generally has three or four steps. The first step is generally a medical assessment. The second is generally a functional assessment. This may involve two parts: first observing sportspeople in training and then involving observing sportspeople in competition. There are a number of people involved in this process beyond the sportsperson including individual classifiers, medical classifiers, technical classifiers, a chief classifier, a head of classification, a classification panel and a classification committee.

Purpose

The purpose of classification in disability sport is to allow fair competition between people with different types of disabilities.[1]

The International Paralympic Committee (IPC) sees its role in developing classification as contributing "to sporting excellence for all Athletes and sports in the Paralympic Movement, [and] providing equitable competition".[2] It sees the purpose of classification as "provid[ing] a structure for Competition. Classification is undertaken to ensure that an Athlete’s impairment is relevant to sport performance, and to ensure that the Athlete competes equitably with other Athletes."[2] According to the IPC, the classification process serves two roles. The first is to determine who is eligible and the second is to group sportspeople for the purpose of competition.[2] The eligibility minimum is an impairment that limits the sportsperson's ability to participate in an activity.[2]

The purpose of disability sport classification is similar to selective classification used in some sports. Such selective criteria include sex, gender, age, weight or size. Selective classification is based on variables that are believed to be predictive of performance, with the goal of minimizing the effect of these variables on outcome even as there is a great range in terms of performance inside these classifications based on other variables. Classification for disability sport is generally not a performance based system where players are grouped based on skill level. These systems include different level leagues in association football and use of a handicap in golf.[3]

History

1940s

Ludwig Guttmann at the Stoke Mandeville Hospital began experimenting with spinal cord injury sport classification systems during the 1940s using a medical based system.[3]

1950s

The classification for spinal cord injury related sports system was developed by International Stoke Mandeville Wheelchair Sports Federation (ISMWSF),[4] with the first system having been created in 1952 by Ludwig Guttmann at the Stoke Mandeville Hospital. This system was published in the Handbook of Rules, which was distributed to people involved with paraplegic sport at the time including coaches, doctors and physiotherapists in various countries. At the time, this classification system was a medical classification.[5] The early history of amputee sport had concurrent histories, with European and American amputee sports developing during the 1950s and 1960s largely independent of each other. In Europe, unilateral and bilateral lower limb amputees participated in sports using prosthetic limbs. In the United States, these types of amputees participated in wheelchair sports instead.[6]

1960s

International Sports Organization for the Disabled (ISOD) was created in 1964, and created the first formalized system of classification to facilitate organized sporting competition between people with different types of amputations. There were originally 27 different classes of different types of amputations. This system proved untenable because of the large number of classes.[7]

1970s

During the 1970s, a debate began to take place in the physical disability sport community about the merits of a medical versus functional classification system. During this period, people had strong feelings both ways but few practical changes were made to existing classification systems.[3]

Adaptive rowing was taking place in France by 1971, with two classes of rowers initially participating: people with visual disabilities and people recovering from polio. People recovering from polio in France used boats with pontoons in order to increase their stability. Other changes were made to the boat with the development of a hinge-system to prevent rowers from tiring as easily. Blind rowers used the same boats during the 1970s and 1980s as their able-bodied counterparts but were guided on the course by a referee.[8] Blind rowers were also encouraged to be in boats with sighted rowers, with the blind rowers serving as the stroke and the cox paying special attention to help the blinder rower. Classification was not something developed in France in this era as there was a focus on integrating rowers into the regular rowing community.[9] In 1976, the total number of amputee classes was reduced to twelve ahead of the 1976 Paralympic Games.[7][10]

Adaptive rowing in the Netherlands began in 1979 with the founding of Stichting Roeivalidatie. There was not an emphasis on classification early on, but rather in integrating adaptive rowing with regular rowing inside of rowing clubs. Attempts were then made to customise equipment to suit an individual rower's specific needs as they related to their disability.[11]

1980s

Wheelchair basketball was the first disability sport to use a functional classification system instead of a medical classification system. Early experiments with this type of classification system in basketball began during the 1980s, with the first demonstration of the system used at the 1983 Gold Cup Championships. At the time, there were four classes for the sport.[12][13] The competition demonstrated that ISMGF medical classifiers had issues with correctly placing players into classes that best represented their ability. The new system increased player confidence and reduced criticism of the classification system as it pertained to accusations that players had been incorrectly classified.[12] The functional classification system used at the 1983 Gold Cup Championships was developed in Cologne based Horst Strokhkendl. This system is the one that has been used consistently in the international community since then.[12][14] It was subsequently used at the 1984 World Games for the Disabled in England.[13] The introduction of a functional classification system also meant that for the first time, amputee players could participate in the sport.[12] Despite the system being in place in time for the 1984 and 1988 Summer Paralympics, a decision was made to delay its use at the Paralympic Games until 1992, where it was used for the first time.[12][13] This was in part a result of conflict between broader ISMGF and the Wheelchair Basketball Subcommittee. The ISMGF was opposed in some measure to fully moving to a functional classification system for the sport. This conflict would not officially resolve itself until 1986, when the United States men and women threatened to boycott major tournaments unless the functional system was fully implemented.[12]

People with cerebral palsy were first included at the Paralympic Games in 1980 in Arnhem, the Netherlands.[15][16] While four classes were in existence at the time, only the two highest functioning classes were included on the program. The four classes were defined around coordination, types of cerebral palsy and functional abilities.[17]

Originally part of a broader organization, CP-ISRA became an independent organization in 1981.[18] National level cerebral palsy and cerebral palsy sport organizations were recognized at the same time.[19] In 1982, the classification system was expanded from four classes to eight classes. It included four ambulatory classes and four wheelchair classes, and used a functional classification system.[17] In 1983, classification for cerebral palsy competitors was undertaken by the CP-ISRA for a variety of sports including boccia and athletics.[20] The classification was based upon the system designed for field athletics events but used in a wider variety of sports including archery and boccia.[21] The system was originally designed with five classifications.[21] The system was designed after consulting medical experts from two other international sport organizations, ISOD and ICPS.[22] They defined cerebral palsy as a non-progressive brain legion that results in impairment. People with cerebral palsy or non-progressive brain damage were eligible for classification by them. The organisation also dealt with classification for people with similar impairments. For their classification system, people with spina bifida were not eligible unless they had medical evidence of loco-motor dysfunction. People with cerebral palsy and epilepsy were eligible provided the condition did not interfere with their ability to compete. People who had strokes were eligible for classification following medical clearance. Competitors with multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy and arthrogryposis were not eligible for classification by CP-ISRA, but were eligible for classification by International Sports Organisation for the Disabled for the Games of Les Autres.[23] At the 1984 Summer Paralympics, the first cerebral palsy only sports were added to the program with the inclusion of CP football and boccia.[24]

During the 1980s, there was a move away from a medical classification system to a functional one, with ISMWSF being one of the organizations driving this change on the wheelchair sport side.[5] Some wheelchair sports saw the introduction of sport specific classification systems during this period, including wheelchair fencing, with the IWF Classification system being implemented for the 1988 Summer Paralympics in Seoul. It had first been used at the European Championships in Glasgow 1987, and was small changes were made to this system before its use at the 1988 Games.[25]

1990s

Starting in the 1990s, changes in the classification system meant that in athletics and swimming, sportspeople with amputations were competing against sportspeople with disabilities like cerebral palsy.[26] Historically up to this point, disability sport has been governed by four different sport organizations: Cerebral Palsy-International Sport and Recreation Association (CP-ISRA;), International Stoke Mandeville Wheelchair Sports Federation (ISMWSF), and ISOD.[27]

In 1991, the International Functional Classification Symposium was held concurrently with the 1991 International Stoke Mandeville Games. Changes were made to the classification system that were formally implemented for the 1992 Summer Paralympics in Barcelona. This system was a more refined form of the original system developed by Guttmann during the 1950s.[5] By 1991, an adaptive rowing classification system was in place for domestic competitions in the United States, but it was still under development. Many rowers also competed against their able-bodied counterparts during this period.[28] The first FISA recognised adaptive rowing World Cup event took place in 1991 and held in the Netherlands.[29] By 1991, an international classification system was attempting to be developed for adaptive rowing.[30] These classes were: Q1: Laesion at C4-C6, Q2: C7-T1, P1: T2-T9, P2: T10-L4, A1: A single amputation, A2: A double amputation and A3: Respiratory problems.[30] While this was nominally a functional classification system, there was a lot of discussion about it as people did not agree on its implementation and it was not universally used.[31] At the same time that this was going on, adaptive rowing was also debating the inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities in their sport.[31]

In 1992, the International Paralympic Committee formally took control of governance for disability sport and oversaw the classification systems as part of a review for any sport seeking IPC recognition.[32]

In 1992, ahead of the Barcelona hosted Paralympics, the amputee sport classification system again was changed with the total number of classes reduced to the nine that currently exist today.[7][33] Despite this, sometimes classes with different levels of performances would compete against each other in the same event for a medal at the Paralympic level.[27] Small changes for amputee sport classification were formalized in 1993.[27]

Wheelchair rugby had been governed by IWAS since 1992, close to the sport's inception. IWAS had also managed the classification side of the sport.[34]

The debate about inclusion of competitors into able-bodied competitions was seen by some disability sport advocates like Horst Strokhkendl as a hindrance to the development of an independent classification system not based on the rules for able-bodied sport. These efforts ended by 1993 as the International Paralympic Committee tried to carve out its own identity and largely ceased efforts for inclusion of disability sport on the Olympic programme.[35] The Games were the first ones where basketball players of different types of disabilities competed against each other, basketball players had a guaranteed right to appeal their classification.[36]

The 1996 Summer Paralympics in Atlanta were the first ones where swimming was fully integrated based on functional disability, with classification no longer separated into classes based on the four disability types of vision impaired, cerebral palsy, amputee, and wheelchair sport. Countries no longer had multiple national swimming teams based on disability type but instead had one mixed disability national team.[15] At the end of 1996, the CP-ISRA had 22 international classifiers.[37] The first classification rules for table tennis published by the International Table Tennis Federation were published in September 1996.[38]

2000s

Following the 2000 Summer Paralympics, there was a push in the wider disability sport community to move away from disability specific classification systems to a more unified classification system that incorporated multiple disability types. By 2000, swimming, table tennis, and equestrian had already done that with amputees being given sport specific classifications for these sports. The desire was to increase the number of sports doing that integration.[27]

Partially because of issues in objectively identifying functionality that plagued the post Barcelona Games, the IPC unveiled plans to develop a new classification system in 2003.[39] This classification system went into effect in 2007, with standards based around identifying impaired strength, limb deficiency, leg length differences, and stature. It also included ways to assess vision impairment and intellectual impairment.[39]

Governance for wheelchair and amputee sport classification was taken over by IWAS following the 2005 merger of ISMWSF and ISOD.[4] In 2009, IPC Athletics classification rules were changed for athletics as a result of recommendations that were approved by the board. These changes affect CP athletes.[40] The CP-ISRA released an updated version of their classification system in 2009.[41]

2010s

In 2010, the International Wheelchair Rugby Federation formally separated from IWAS and took over management of classification of their sport themselves.[34] In 2010, the IPC announced that they would release a new IPC Athletics Classification handbook that specifically dealt with physical impairments. This classification guide would be put into effect following the closing ceremony of the 2012 Summer Paralympics.[42] In 2011, IWAS and CPISRA signed a memorandum of understanding that allowed people with spinal cord injuries to compete in CPISRA race running events.[43] When World Taekwondo Federation initially launched the para-side of their sport, they used the classification system of CP-ISRA but moved to their own code in consultation with the CP-ISRA in 2015.[44]

Governance

Governance of disability sport classification has historically been controlled by two groups: specific disability type sport organizations that cover multiple sports, and specific sport organizations that cover multiple disability types.[1]

In terms of specific disability sport organizations (IFs), there have historically been six big organizations governing classification. They are CPISRA has for cerebral palsy and head injuries, ISMWSF for spinal cord injuries, ISOD for orthopaedic conditions and amputees, INAS for people with intellectual disabilities, IBSA for blind and vision impaired athletes.[1][45] As members of the IPC, they are required to comply with classification code spelled out by the IPC on how to establish and maintain a classification system.[2]

International sports federations (ISFs) started to transition into the role of handling classification for their sports during the 1990s.[25] Among the sports where ISFs are in charge of classification for some disability types are athletics, alpine skiing, wheelchair rugby and lawn bowls.[34][46]

| Sport | Amputees | Cerebral palsy | Spinal cord injuries | Les Autres | Intellectual disabilities | Vision impairments | Deaf | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpine skiing | IPC Alpine Skiing | IPC Alpine Skiing | IPC Alpine Skiing | IPC Alpine Skiing | International Sports Federation for Persons with Intellectual Disability | IPC Alpine Skiing | International Committee of Sports for the Deaf | [2][45][47][48][49] |

| Archery | Para-Archery International Archery Federation (FITA) | Para-Archery International Archery Federation (FITA) | Para-Archery International Archery Federation (FITA) | Para-Archery International Archery Federation (FITA) | [2][50] | |||

| Athletics | IPC Athletics | IPC Athletics | IPC Athletics | IPC Athletics | IPC Athletics | IPC Athletics | International Committee of Sports for the Deaf | [2][45][49][51] |

| Badminton | International Committee of Sports for the Deaf | [49] | ||||||

| Basketball | International Sports Federation for Persons with Intellectual Disability | International Committee of Sports for the Deaf | [48][49] | |||||

| Beach volleyball | International Committee of Sports for the Deaf | [49] | ||||||

| Biathlon | IPC Biathlon | IPC Biathlon | IPC Biathlon | [2][45][47] | ||||

| Boccia | Boccia International Sports Federation | Boccia International Sports Federation | Boccia International Sports Federation | [2][50] | ||||

| Canoe | International Canoe Federation | International Canoe Federation | [50] | |||||

| Cross country skiing | IPC Cross Country Skiing | IPC Cross Country Skiing | IPC Cross Country Skiing | [2][45][47] | ||||

| Cycling | Para-Cycling International Cycling Union | Para-Cycling International Cycling Union | Para-Cycling International Cycling Union | International Sports Federation for Persons with Intellectual Disability | Para-Cycling International Cycling Union | International Committee of Sports for the Deaf | [48][50][52] | |

| Electric wheelchair hockey | IWAS Committee Electric Wheelchair Hockey (ICEWH) | IWAS Committee Electric Wheelchair Hockey (ICEWH) | IWAS Committee Electric Wheelchair Hockey (ICEWH) | [53] | ||||

| Equestrian | International Equestrian Federation | International Equestrian Federation | International Equestrian Federation | International Equestrian Federation | International Equestrian Federation | International Equestrian Federation | [2][50][54] | |

| Football | World Amputee Football | Cerebral Palsy International Sport & Recreational Association | International Sports Federation for Persons with Intellectual Disability | International Blind Sport Federation | International Committee of Sports for the Deaf | [2][48][49][50][55][56] | ||

| Goalball | International Blind Sport Federation | [50] | ||||||

| Ice sledge hockey | IPC Ice Sledge Hockey | IPC Ice Sledge Hockey | IPC Ice Sledge Hockey | IPC Ice Sledge Hockey | [45][47] | |||

| ID cricket | International Sports Federation for Persons with Intellectual Disability | [48] | ||||||

| ID handball | International Sports Federation for Persons with Intellectual Disability | [48] | ||||||

| Judo | International Blind Sport Federation | International Committee of Sports for the Deaf | [50] | |||||

| Lawn bowls | International Bowls for the Disabled | International Bowls for the Disabled | International Bowls for the Disabled | International Bowls for the Disabled | International Bowls for the Disabled | [46] | ||

| Powerlifting | IPC Powerlifting | IPC Powerlifting | IPC Powerlifting | [2][50] | ||||

| Race Running | IWAS | CPISRA | IWAS | [43] | ||||

| Rowing | International Rowing Federation | International Rowing Federation | International Rowing Federation | International Rowing Federation | International Rowing Federation | [2][50][57][58] | ||

| Sailing | International Association for disabled Sailing | International Association for disabled Sailing | International Association for disabled Sailing | International Sports Federation for Persons with Intellectual Disability | [48][50] | |||

| Shooting | IPC Shooting | IPC Shooting | IPC Shooting | International Committee of Sports for the Deaf | [2][45][50] | |||

| Sitting volleyball | World Organisation Volleyball for Disabled | World Organisation Volleyball for Disabled | World Organisation Volleyball for Disabled | [2][50] | ||||

| Swimming | IPC Swimming | IPC Swimming | IPC Swimming | IPC Swimming | IPC Swimming | IPC Swimming | International Committee of Sports for the Deaf | [45][50] |

| Table tennis | International Table Tennis Federation | International Table Tennis Federation | International Table Tennis Federation | International Table Tennis Federation | International Committee of Sports for the Deaf | [2][50] | ||

| Taekwondo | Para-Taekwondo (WTF) | International Sports Federation for Persons with Intellectual Disability | International Committee of Sports for the Deaf | [48][50] | ||||

| Ten-pin bowling | International Committee of Sports for the Deaf | [49] | ||||||

| Tennis | International Sports Federation for Persons with Intellectual Disability | International Committee of Sports for the Deaf | [48] | |||||

| Triathlon | Paratriathlon - International Triatholon Union | Paratriathlon - International Triatholon Union | Paratriathlon - International Triatholon Union | Paratriathlon - International Triatholon Union | International Committee of Sports for the Deaf | [50] | ||

| Wheelchair basketball | International Wheelchair Basketball Federation | International Wheelchair Basketball Federation | International Wheelchair Basketball Federation | [2][50] | ||||

| Wheelchair curling | World Curling Federation | World Curling Federation | World Curling Federation | [2][47] | ||||

| Wheelchair dance | IPC Wheelchair Dance | [2][45] | ||||||

| Wheelchair fencing | IWAS Wheelchair Fencing | IWAS Wheelchair Fencing | IWAS Wheelchair Fencing | [2][25] | ||||

| Wheelchair floorball | International Committee Wheelchair Floorball | [50] | ||||||

| Wheelchair rugby | International Wheelchair Rugby Federation | International Wheelchair Rugby Federation | [2][34] | |||||

| Wheelchair tennis | International Tennis Federation | International Tennis Federation | International Tennis Federation | [2][50] |

Disability groups

Disability sport classification is open to a variety of different groups with specific types of disabilities. These disabilities need to be permanent in nature.[1] Historically, there have been several different groups of disabilities. These include people with vision impairments, physical disabilities, intellectual disabilities. Physical disabilities is often broken down into several subcategories including spinal injuries, cerebral palsy, amputations and Les Autres.[1]

The International Paralympic Committee's 2016 document International Standard for Eligible Impairments September 2016 describes eligible impairments for competing in paralympic sports. [59]The document also states that "Any Impairment that is not listed in this International Standard as an Eligible Impairment is referred to as a Non-Eligible Impairment (p.6). The document provides specific examples of health conditions that are deemed ineligible, which include fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (p.8).[59]

Amputations and other orthopedic conditions

Amputee sports classification is a disability specific sport classification used for disability sports to facilitate fair competition among people with different types of amputations.[60][27] This classification was set up by International Sports Organization for the Disabled (ISOD), and is currently managed by IWAS who ISOD merged with in 2005.[61] Several sports have sport specific governing bodies managing classification for amputee sportspeople.[62]

Classification for amputee athletes began in the 1950s and 1960s. By the early 1970s, it was formalized with 27 different classes. This was reduced to 12 in 1976, and then down to 9 in 1992 ahead of the Barcelona Paralympics. By the 1990s, a number of sports had developed their own classification systems that in some cases were not compatible with the ISOD system. This included swimming, table tennis and equestrian as they tried to integrate multiple types of disabilities in their sports. Amputee sportspeople have specific challenges that different from other types of disability sportspeople.[6][7][10][27]

The classes for ISOD's amputee sports classification system are A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, A6, A7, A8 and A9. The first four are for people with lower limb amputations. A5 through A8 are for people with upper limb amputations. A9 is for people with combinations of upper and lower limb amputations. The classification system is largely medical, and generally has four stages. The first is a medical examination. The second is observation at practice or training. The third is observation during competition. The final is being put into a classification group. There is some variance to this based on sport specific needs.[6][7][10][63]

| Class | Descriptions | Abbr | Athletics | Cycling | Skiing | Swimming | Comparable classifications in other sports | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Bilateral above the knee lower limb amputations | A/K | T54, F56, F57, F58 | LC4 | LW1, LW12.2 | S4, S5, S6 | Badminton: W3.

Lawn bowls: LB1. Powerlifting: Weight specific class. Sitting volleyball: Open. Sitzball: Open. Ten-pin bowling: TPB8. Wheelchair basketball: 3-point player, 3.5-point player Wheelchair fencing: 3 |

[7][33][64][65][66][67][4][68][69][70][25] |

| A2 | Unilateral above the knee lower limb amputations | A/K | T42, T54, F42, F58 | LC2, LC3 | LW 2 | S7, S8 | Amputee basketball: Open.

Amputee football: Field player. Lawn bowls: LB2. Sitting volleyball: Open. Sitzball: Open. Ten-pin bowling: TPB8, TPB9 Wheelchair basketball: 4-point player. Cerebral palsy: CP3. |

[7][33][64][65][66][67][4][68][69][26] |

| A3 | Bilateral below the knee lower limb amputations | B/K | T43, F43, T54, F58 | LC4 | LW 3 | S5, S7, S8 | Badminton: W3.

Lawn bowls: LB1, LB2. Powerlifting: Weight specific class. Sitting volleyball: Open. Sitzball: Open. Ten-pin bowling: TPB8, TPB9. Cerebral palsy: CP4. Wheelchair basketball: 4-point player, 4.5-point player. |

[7][33][64][65][67][4][68][69][70][26] |

| A4 | Unilateral below the knee lower limb amputations | B/K | T44, F44, T54 | LC2, LC3 | LW 4 | S10 | Amputee basketball: Open.

Amputee football: Field player. Lawn bowls: LB2. Sitting volleyball: Open. Sitzball: Open. Ten-pin bowling: TPB8, TPB9. Wheelchair basketball: 4-point player, 4.5-point player. |

[7][33][64][65][66][67][4][68][69] |

| A5 | Bilateral above the elbow upper limb amputations | A/E | T45, F45 | LC1 | LW5/7-1, LW5/7-2 | S7 | Lawn bowls: LB3.

Sitzball: Open. |

[7][33][64][65][66][4][69] |

| A6 | Unilateral above the elbow upper limb amputations | A/E | T46, F46 | LC1 | LW6/8.1 | S7, S8, S9 | Amputee basketball: Open.

Amputee football: Goalkeeper. Lawn bowls: LB3. Sitzball: Open. Ten-pin bowling: TPB10. |

[7][33][64][65][66][67][4][69] |

| A7 | Bilateral below the elbow upper limb amputations | B/E | T45, F45 | LC1 | LW 5/7-3 | S7 | Lawn bowls: LB3.

Sitzball: Open. |

[7][33][64][65][66][67][4][69] |

| A8 | Unilateral below the elbow upper limb amputations | B/E | T46, F46 | LC1 | LW 6/8.2 | S8, S9 | Amputee basketball: Open.

Amputee football: Goalkeeper. Badminton: STU5. Lawn bowls: LB3. Sitzball: Open. Ten-pin bowling: TPB10. |

[7][33][64][65][66][67][4][69] |

| A9 | Combination of amputations of the upper and lower limbs. | T42, T43, T44, F42, F43,

F44, F56, F57, F58 |

LW9.1, LW9.2 | S2, S3, S4, S5 | Amputee basketball: Open.

Lawn bowls: LB1, LB2. Sitting volleyball: Open. Sitzball: Open. Ten-pin bowling: TPB8, TPB9. Wheelchair basketball: 2-point player, 3-point player, 4-point player. |

[7][33][64][65][66][67][4][68] |

Cerebral palsy and other neurological disorders

Cerebral palsy sport classification is a classification system used by sports that include people with cerebral palsy (CP) with different degrees of severity to compete fairly against each other and against others with different types of disabilities. In general, Cerebral Palsy-International Sports and Recreation Association (CP-ISRA) serves as the body in charge of classification for cerebral palsy sport, though some sports have their own classification systems which apply to CP sportspeople.[22][71][72][73][74]

People with cerebral palsy were first included at the Paralympic Games in 1980 in Arnhem, the Netherlands at time when there were only four CP classes.[15][16] In the next few years, a CP sports specific international organization, CP-ISRA, was founded and took over the role of managing classification. The system then started to move away from a medical based classification system to a functional classification system.[22][71][72] This was not without controversy as it represented a move to allow people with different types of disabilities to compete against each other, and there was pushback as a result. A major overhaul of classification took place during the 2000s. At the same, individual sports began to develop their own sport specific classification systems.[16][72][74][75]

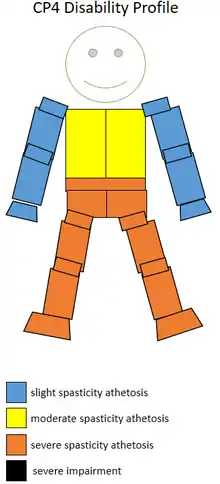

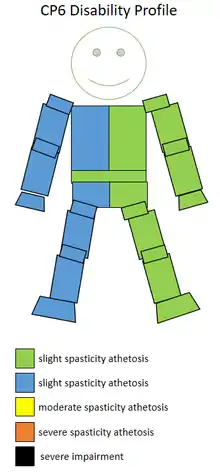

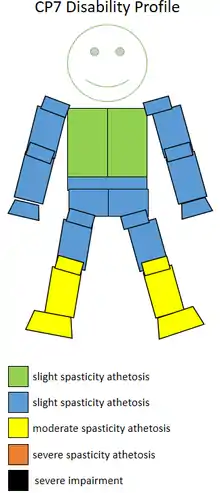

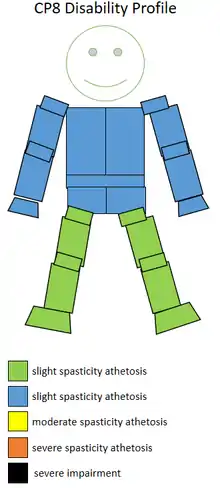

The classification system developed by the CP-ISRA includes eight classes: CP1, CP2, CP3, CP4, CP5, CP6, CP7 and CP8. These classes can be generally grouped into upper wheelchair, wheelchair and ambulatory classes. CP1 is the class for upper wheelchair, while CP2, CP3 and CP4 are general wheelchair classes. CP5, CP6, CP7 and CP8 are ambulatory classes.[18][64][76][77]

Disability type for CP1 classified sportspeople

Disability type for CP1 classified sportspeople Disability type for CP2 classified sportspeople

Disability type for CP2 classified sportspeople Disability type for CP3 classified sportspeople

Disability type for CP3 classified sportspeople Disability type for CP4 classified sportspeople

Disability type for CP4 classified sportspeople Disability type for CP5 classified sportspeople

Disability type for CP5 classified sportspeople Disability type for CP6 classified sportspeople

Disability type for CP6 classified sportspeople Disability type for CP7 classified sportspeople

Disability type for CP7 classified sportspeople Disability type for CP8 classified sportspeople

Disability type for CP8 classified sportspeople

Some sports have historically used these categories without much sport specific classification done. This is the case for CP football, which uses and is only open to CP5, CP6, CP7 and CP8 classes.[78] CP football sometimes uses different classification names, with FT5 mirroring CP5, FT6 mirroring CP6, FT7 mirroring CP7 and FT8 mirroring CP8.[79] Rules for the sport require that at least one CP5 or CP6 player be on the field at any given moment, and if a team is unable to do so, they play down a man.[33]

Different sports utilize different classes, with some of these systems mirroring the classes used by the CP-ISRA, while at the same time allowing athletes to compete against people with similar functional disabilities. Athletics have one such system, with classes T31 to T38 mirror CP1 to CP8 for track events, and F31 to F38 for field events.[64] This is not always the case though, and some CP athletes may be grouped in T and F classes in the 50s for people who use wheelchairs. CP2 athletes may be grouped in F52 or F53. CP3 athletes may be classified as F53, F54, or F55. CP4 athletes may be classified as F54, F55 or F56. CP5 athletes may be classified as F56.[80][81][82]

The classification utilized by the UCI does not mirror the system used by CP-ISRA. Instead, eligible classes include T1, T2, H1, C3, and C4. People with CP1, CP2, CP3 and CP4 are classified as T1 and use a tricycle.[83][84] CP5 and CP6 competitors are eligible to compete in the bicycle class C3.[84] CP7 and CP8 may compete on a bicycle in the C4 class.[83][84] CP3 are eligible to compete in the handcycle H1 class.[84]

Swimming also does not use CP-ISRA related classes. People with hemiplegic forms of cerebral palsy are classified as S8, S9 or S10 depending on the severity of the hemiplegia.[85] Table tennis is the same, with classes being open to CP competitors but not using the CP-ISRA system as a guide for how to classify table tennis players. Classes 6, 7, 8 and 9 in table tennis are all available for people with cerebral palsy, with a sports specific classification process to determine which class they belong to often based more on arm and hand functionality than other sports.[77]

Some sports like powerlifting do not have different classes. Rather, everyone competes in classes based on weight, with minimum and maximum disability requirements existing. The CP-ISRA classes of CP3, CP4, CP5, CP6, CP7 and CP8 are eligible to participate in powerlifting.[78][86][87] Wheelchair curling is the same, with CP-ISRA classes of CP3, CP4 and CP5 all eligible to participate in the sport.[78][86][87] Sledge hockey and wheelchair dance are similar, with the highest eligible class of participants being CP7.[77][87] Standing volleyball, open to people with different types of disabilities, is also similar, but is limited to only to CP7 and CP8 competitors.[77]

| Class | Definition | Athletics | Boccia | Cycling | CP Football | Race Running | Rowing | Skiing | Swimming | Other sports | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP1 | Use electric wheelchairs and are quadriplegic. | T31, F31 | BC1, BC3 | T1 | RR1 | S1, S2 | Slalom: CP1 | [18][77][78][82][86][87][79][83] | |||

| CP2 | Use electric wheelchairs and are quadriplegic. Have better upper body control when compared to CP1. | T32,F32, F51, F52, F53 | BC1, BC2 | T1 | RR2 | S2 | Slalom: CP2 | [18][64][82][87] | |||

| CP3 | Use wheelchairs on a daily basis though they may be ambulant with the use of assistive devices. Have issues with head movement and trunk function. | T33, F33, F53, F54, F55 | T1, H1 | RR2, RR3 | LW10, LW11 | S3, S4 | Slalom: CP3 | [87] | |||

| CP4 | Use wheelchairs on a daily basis though they may be ambulant with the use of assistive devices. Have fewer issues with head movement and trunk function. | T34, F34, F54, F55, F56 | T1 | RR3 | AS | LW10, LW11, LW12 | S4, S5 | Slalom: CP4 | [57] | ||

| CP5 | Greater functional control of their upper body, and are generally ambulant with the use of an assistive device. Quick movements can upset their balance. | T35, F35, F56 | T2, C3 | FT5 | RR3 | TA | LW1, LW3, LW3/2,LW4 LW9 | S5, S6 | [33][57][77][78][79][89][87] | ||

| CP6 | Ambulatory, and able to walk without the use of an assistive device. Their bodies are constantly in motion. | T36, F36 | T2, C3 | FT6 | RR3 RR4 | LW1, LW3 LW3/2, LW9 | S7 | [18][64][90][91] | |||

| CP7 | Able to walk, but may appear to have a limp as half their body is affected by cerebral palsy. | T37,F37 | C4 | FT7 | RR4 | LW9, LW9/1, LW9/2 | S7, S8, S9, S10 | Sitting volleyball: Grade A | [18][77][78][82][86][87][79][83] | ||

| CP8 | Least physically affected by their cerebral palsy, with their disability generally manifested as spasticity in at least one limb. | T38, F38 | C4 | FT8 | LTA | LW4, LW6/8, LW9, LW9/2 | S8, S9, S10 | Sitting volleyball: Grade A | [18][77][78][82][86][87][79][83] |

Deaf and hearing impaired

Inside deaf sport governed by International Committee of Sports for the Deaf, deaf sportspeople compete only against other people with minimal hearing loss of at least 55 decibels.[92]

Sometimes, deaf sportspeople are integrated into competitions with other disability and non-disability sportspeople. They compete in their own classification indicating they are deaf.[64] Because of a lack of deaf sport integration with the IPC, these classifications may be only used nationally. For example, T01 is used for deaf sportspeople only in Australia.[93][94]

Swimming is another sport that sometimes has national level integration with different national classes. In Australia, deaf swimmers are classified as S15.[95] In Scotland, it is handled by GB Deaf Swimming Club through UK Deaf Sport and internationally by ICSD.[96]

Eligibility for the deaf football class in England through The FA is based on proof membership in UK Deaf Sports, an ICSD identification card or a letter from an audiologist, GP or a specialist consultant stating that the athlete has a hearing loss of 41 dB or more.[56] Leagues in the UK are often separated into four separate classes: Moderate with hearing loss between 41 and 55 dB, moderately severe with hearing loss between 56 and 70 dB, severe with hearing loss between 71 and 90 dB, and profound with hearing loss greater than 91 dB .[56]

Cycling in Australia has two classes. AU1 is for domestic competitions for deaf cyclists. AU2 is for Australian deaf cyclists wishing to compete abroad. Classification is handled domestically by Deaf Sports Australia, and internationally by ICSD.[97]

| ID Sport | Australia | Great Britain | United States | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Athletics | T01, ED | T60, F60 | [64][94][98] | |

| Cycling | AU1, AU2 | [97] | ||

| Football | Deaf: Moderate

Deaf: Moderately severe Deaf: Severe Deaf: Profound |

[56] | ||

| Swimming | S15 | S15 | [95][96] |

Intellectual disabilities

International Sports Federation for Persons with Intellectual Disability (INAS) is the governing body for competitive sport for people with intellectual disabilities.[99][100][101][102][103] At the Paralympic Games, the relevant international sport organization takes over classification.[103] In Australia, classification on the national level is governed by the Australian Paralympic Committee and Australian Sport and Recreation Association for People with Integration Difficulties.[95][102][103] Sportspeople classified nationally in Australia are not guaranteed that they will meet international classification standards.[103] Locally, Australian eligibility may also be handled by Lifestream Australia.[104] As it relates to sport specific classification in Australia, Swimming Australia supports the relevant classifying agencies in classification assessment.[95] In New Zealand, classification for ID sportspeople is handled by Paralympics New Zealand.[105] In the United Kingdom, classification may be handled on a sport specific basis in partnership with UK Sports Association. For athletics, this is handled by British Athletics.[106][107] For swimming in Scotland, it is handled by Scottish Disability Sport in partnership with British Para-Swimming.[96]

Testing has shown that people with intellectual disabilities often have less strength, endurance, agility, flexibility, balance and slower running speeds than the non-disabled. They also lower peak heart rates and lower peak oxygen uptake.[108] Many people with intellectual disabilities also have hearing or vision related disabilities.[108] People with Down syndrome often have a condition called ligamentous laxity, which results in increased flexibility in their joints of their neck. 15% of people with Down syndrome have atlantoaxial instability and causes decreases in muscle tone.[108][109] This places them at increased risk of spinal cord injuries.

Intellectual disabilities cause issues with sport performance because of issues with reaction time and processing speed, attention and concentration, working memory, executive function, reasoning and visual-spatial perception. These things are all important components of sports intelligence.[110] Successful coaching strategies differ from other sports. Coaches need to be more effusive with praise, not assume that athletes will understand and retain what they are told, focusing on improving overall physical ability to improve competition performance, focus more skills while playing rather than as independent drills removed from the sport, and revisit concepts often.[111] People with mild levels of intellectual disability have performance levels similar to non-disabled sportspeople.[108]

Sometimes, sportspeople with intellectual disabilities are integrated into competitions with other disability and non-disability sportspeople. They compete in their own classification indicating they have such a disability.[64]

| ID Sport | Internationally | Australia | Great Britain | United States | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Athletics | T20, F20 | T20, F20, ID | [64][107][112][113][114] | ||

| Adaptive rowing | ID | II | RSS-LD | ID, LTA, TA, AS | [57][115] |

| Cycling | I1, I2 | [116] | |||

| Equestrian | Grade III | Grade III | [54] | ||

| ID football | ID | Learning Disability | [55][56] | ||

| Swimming | S14 | [107][113][114][117] | |||

| Table tennis | Class 11 | [107][113][114][118] |

Some sports are not open via their IFs to people with intellectual disabilities on the elite level. This includes cycling.[52] It is also true for lawn bowls and sailing.[119][120] Some sports are deliberately not supported by INAS-FID because of concerns about safety for sportspeople. These sports including pole vaulting, platform diving, boxing, ski jumping, American football, rugby, wrestling, karate, javelin, discus, hammer throw, and trampolining.[109] Sports supported by the Special Olympics including track and field, soccer, basketball, ten-pin bowling, and aquatics.[108] Many of these sports have local and national organizations that have signed memorandums of understanding with their national Special Olympics organizations, with Gymnastics Australia being an example in Australia.[121] Classification for Special Olympics often uses groupings based on performance times or performance levels. This is different from the Paralympics where classification is done based on function or medical definitions.[108]

Les autres

The purpose of Les Autres sport classification is to allow for fair competition between people of different disability types.[1] Les Autres sport classification is handled by International Sports Organization for the Disabled (ISOD).[122] The Les Autres class of disabilities generally covers two classes. These are people with short stature and people with impaired passive range of movement. The latter is sometimes referred to as PROM.[123] People with short stature have this issue as a result of congenital issues.[123] PROM includes people with joint disorders including arthrogryposis and thalidomide. Most of the included specific conditions are for congential disorders.[123] It also includes people with multiple sclerosis. This grouping does not include people with dislocated muscles or arthritis.[123]

There are a number of sports open to people who fit into Les Autres classes, though their eligibility often depends on if they have short stature or PROM. For people with short stature, these sports include equestrian, powerlifting, swimming, table tennis and track and field.[123] For people with PROM, these sports include archery, boccia, cycling, equestrian, paracanoe, paratriathlon, powerlifting, rowing, sailing, shooting, swimming, table tennis, track and field, wheelchair basketball, wheelchair fencing and wheelchair tennis.[123]

LAF1, LAF2 and LAF3 are wheelchair classes, while LAF4, LAF5 and LAF6 are ambulant classes.[67]

| Class | Definition | Archery | Athletics | Equestrian | Swimming | Other sports | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAF1 | Wheelchair class. Severe issues with all four limbs. Impairment in dominant arm. | ARW1 | F51, F52, F53 | Grade 1 | Skiing: LW10

Powerlifting: Weight based Sitting volleyball: Minimal disability |

[64][67][124][125][126][127][128] | |

| LAF2 | Wheelchair class. Low to moderate levels of balance issues while sitting. Severe impairment of three limbs, or all four limbs but to a lesser degree than LAF1, Normal arm function. | ARW1, ARW2 | F53 | Grade 1 | Powerlifting: Weight based

Sitting volleyball: Minimal disability Skiing: LW11 |

[64][67][124][125][126][127] | |

| LAF3 | Wheelchair or wheelchair class. Reduced muscle function. Normal trunk functionality, balance and use of their upper limbs. Weakness in one leg muscle or who have joint restrictions. Limited function in at least two limbs. | ARW2 | T44, F54, F55, F56, F57, F58 | Grade 1 | Powerlifting: Weight based

Sitting volleyball: Minimal disability Skiing: LW12 |

[64][67][124][125][126][127][129] | |

| LAF4 | Ambulant class. Difficulty moving or severe balance problems. Reduced upper limb function. Limited function in two limbs to a lesser extent than LAF3. | ARST | T46, F58 | Grade 4 | CP football: CP5

Powerlifting: Weight based Sitting volleyball: Minimal disability |

[64][67][125][127][130][131] | |

| LAF5 | Ambulant class. Normal upper limb functionality but who have balance issues or problems with their lower limbs. Limited function in at least one limb. | ARST | F42, F43, F44 | Grade 4 | Powerlifting: Weight based

Sitting volleyball: Minimal disability Triathlon: TRI3 |

[64][67][125][127][130][132] | |

| LAF6 | Ambulant class. Minimal issues with trunk and lower limb functionality. Impairments in one upper limb. Minimal disability. | ARST | F46 | Grade 4 | Powerlifting: Weight based

Sitting volleyball: Minimal disability Triathlon: TRI4 |

[64][67][125][127][130][132] | |

| SS1 | Short stature. Male standing height and arm length added together are equal to or less than 180 centimetres (71 in). Female standing height and arm length added together are equal to or less than 173 centimetres (68 in). | T40, F40 | S2, S5, S6 | Powerlifting: Weight based

Sitting volleyball: Minimal disability |

[64][127][65] | ||

| SS2 | Short stature. Male standing height and arm length added together are equal to or less than 200 centimetres (79 in). Female standing height and arm length added together are equal to or less than 190 centimetres (75 in). | T41, F41 | S6 | Powerlifting: Weight based

Sitting volleyball: Minimal disability |

[64][127][65] |

There are a number of sports open to people who fit into Les Autres classes, though their eligibility often depends on if they have short stature or PROM. For people with short stature, these sports include equestrian, powerlifting, swimming, table tennis and track and field.[123] For people with PROM, these sports include archery, boccia, cycling, equestrian, paracanoe, paratriathlon, powerlifting, rowing, sailing, shooting, swimming, table tennis, track and field, wheelchair American football, wheelchair basketball, wheelchair fencing, wheelchair softball and wheelchair tennis.[123][125][134] Historically, a number of sports were closed internationally to LA sportspeople including boccia, CP football, wheelchair fencing, wheelchair rugby and wheelchair tennis.[135]

Some sports have open classification, with all Les Autres and short stature classes able to participate so long as they meet the minimal definition of having a disability. This was true for powerlifting.[131][136][137] In athletics, the T40s and F40s classes include Les Autres classes.[131][137][138] Les Autres competitors can also participate in sitting volleyball. In the past, the sport had a classification system and they were assigned to one of these classes. The rules were later changed to be inclusive of anyone, including Les Autres players, who meet the minimum disability requirement.[127][137] In Nordic and alpine skiing, Les Autres competitors participate in different classes depending on their type of disability and what is effected.[124] Wheelchair softball uses a point system similar to wheelchair basketball.[125] Wheelchair American football requires at least one of the six football players on the field be a tetraplegic or woman with a disability.[125] In CP soccer, rules requiring a CP5 player on the field led to wider adoption of Les Autres classes into the CP classification system to facilitate comparable participation.[131]

Spinal cord injuries

Wheelchair sport classification includes a number of disabilities that cause problems with the spinal cord. These include paraplegia, quadriplegia, muscular dystrophy, post-polio syndrome and spina bifida.[123]

In general, classification for spinal cord injuries and wheelchair sport is overseen by IWAS.[45][139] Some sports have classification managed by other organizations. In the case of athletics, classification is handled by IPC Athletics.[51] Wheelchair rugby classification has been managed by the International Wheelchair Rugby Federation since 2010.[34] Lawn bowls is handled by International Bowls for the Disabled.[46] Wheelchair fencing is governed by IWAS Wheelchair Fencing (IWF).[25] The International Paralympic Committee manages classification for a number of spinal cord injury and wheelchair sports including alpine skiing, biathlon, cross country skiing, ice sledge hockey, powerlifting, shooting, swimming, and wheelchair dance.[45]

| Class | Historical name | Neurological level | Athletics | Cycling | Swimming | Other sports | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1/T1/SP1 | 1A Complete | C6 | F51 | H1 | S1, S2 | Archery: ARW1

Electric wheelchair hockey: Open Wheelchair fencing: 1A/Category C |

[140][67][65][25][53][141][142][143] |

| F2/T2/SP2 | 1B Complete, 1A Incomplete | C7 | F52 | H2 | S1, S2, SB3, S4 | Archery: ARW1

Electric wheelchair hockey: Open Ten pin bowling: TPB8 Wheelchair fencing: 1B/Category C |

[140][67][65][25][53][141][142][143][4][133] |

| F3/T3/SP3 | 1C Complete, 1B Incomplete | C8 | F52, F53 | H3 | S3, SB3, S4, S5 | Archery: ARW1, ARW2

Electric wheelchair hockey: Open Rowing: AS Table tennis: Grade 3, Grade 4, Grade 5 Wheelchair fencing: 1B/Category C |

[140][67][65][25][53][141][142][143][4][133][3] |

| F4/T4/SP4 | 1C Incomplete, 2, Upper 3 | T1 - T7 | F54 | H4, H5 | S3, SB3, SB4, S5 | Archery: ARW2

Rowing: AS Wheelchair basketball: 1-point player Wheelchair fencing: 2/Category B |

[140][67][65][25][141][143][4][133][144][145] |

| F5/SP5 | Lower 3, Upper 4 | T8 - L1 | F55 | SB3, S4, SB4, S5, SB5, S6 | Archery: ARW2

Rowing: TA Wheelchair basketball: 2-point player Wheelchair fencing: 2, 3/Category B, A |

[140][67][65][25][141][4][133][144][145] | |

| F6/SP6 | Lower 4, Upper 5 | L2 - L5 | F56 | S5, SB5, S7, S8 | Wheelchair basketball: 3-point player, 4-point player

Wheelchair fencing: 3, 4/Category A |

[140][67][65][25][141][4][133][144][145] | |

| F7/SP7 | Lower 5, 6 | S1 - S2 | F57 | S5, S6, S10 | Rowing: LTA

Wheelchair basketball: 4-point player Wheelchair fencing: 4/Category B |

[140][67][65][25][141][144][145] | |

| F8/SP8 | F42, F43, F44, F58 | S8 | [140][67][65][141] | ||||

| F9/SP9 | F42, F43, F44 | [140][67] |

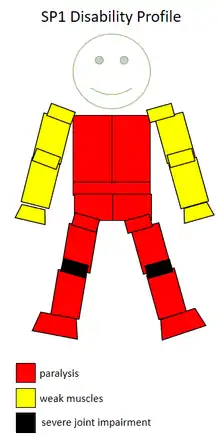

Profile of an F1 sportsperson

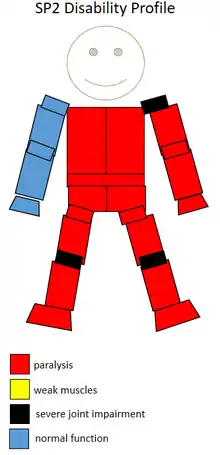

Profile of an F1 sportsperson Profile of an F2 sportsperson

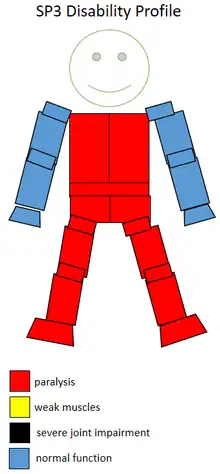

Profile of an F2 sportsperson Profile of an F3 sportsperson

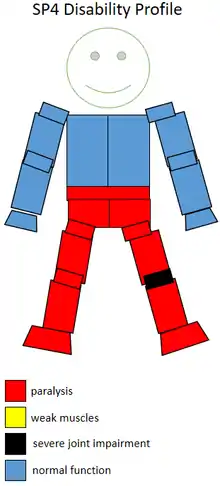

Profile of an F3 sportsperson Profile of an F4 sportsperson

Profile of an F4 sportsperson Profile of an F5 sportsperson

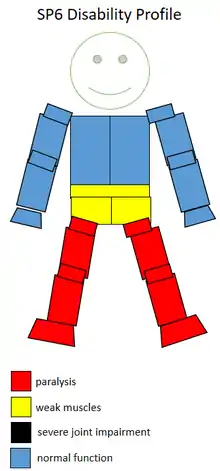

Profile of an F5 sportsperson Profile of an F6 sportsperson

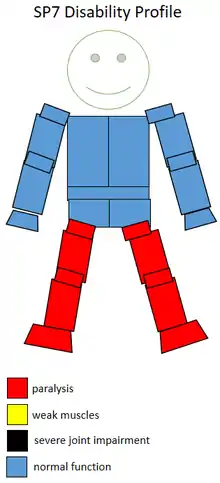

Profile of an F6 sportsperson Profile of an F7 sportsperson

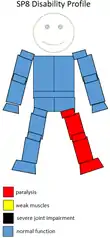

Profile of an F7 sportsperson Profile of an F8 sportsperson

Profile of an F8 sportsperson Athletics specific classification for wheelchair sport athletes showing T51, T52, T53 and T54 spinal injury locations.

Athletics specific classification for wheelchair sport athletes showing T51, T52, T53 and T54 spinal injury locations.

Vision impaired

The classification system for blind and vision impaired sport often has comparable classes in other sports.[64]

| Class | Athletics | Cycling | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | T11, F11 | Tandem | [52][64][66] | |

| B2 | T12, F12 | Tandem | [52][64][66] | |

| B3 | T13, F13 | Tandem | [52][64][66] |

Transplants, diabetics, epileptics and other groups with disabilities

Historically, disability sports classification has not been open specifically to people with transplants, diabetics and epileptics. This is because disabilities need to be permanent in nature.[1] On the Paralympic level, this also extends to people with disabilities related to tactile sensation, impaired thermoregulatory and cardiac function. Some of this is because while these may affect sport performance, they are not covered by the culture of the Paralympic Movement.[3]

Some competitions are open to people with these disability types. Special classifications may be used to allow them to compete in some events.[64] Some sports had classifications for people with these types of disabilities, but phased them out. For example, rowing's first classification system in 1991 had an A3 class for people with respiratory problems.[30] Classification for transplantees in Australia is handled by Transplant Australia.[94]

| Sport | Disability type | Definition | Australia | England | United States | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Athletics | Transplantee | Someone who has had kidney, heart, heart and lung, liver or bone marrow transplant. | T60, F60 | T60, F60 | [64][94] | |

| Football | Mental health | "individuals who have experienced acute or enduring mental health problems and are living in the community or a hospital setting."[56] | Mental Health | [56] | ||

| Swimming | Transplantee | S16 | [95] |

Functional classification

Since the 1990s, there has been a move away from many of these sport specific disability type classifications and into a more functional classification system that allows sportspeople with different types of disabilities to compete fairly against each other. This classification system tends to use a number of measures to classify sportspeople including muscle strength, range of joint movement (ROM), co-ordination, amputation, body height and balance.[1] The importance of these various measures then changes based on sport specific needs.[1]

Classification process

Athlete evaluation

Classification generally has three or four steps. The first step is generally a medical assessment. The second is generally a functional assessment. This may involve two parts: first observing a sportspeople in training and then involving observing sportspeople in competition. The last step is the sportsperson being put into a class and being given a classification status.[52][146][147][25][53]

Medical classification

The type of medical information required may be sport specific or disability type specific. Medical classification for wheelchair sport can consist of medical records being sent to medical classifiers at the international sports federation. The sportsperson's physician may be asked to provide extensive medical information including medical diagnosis and any loss of function related to their condition. This includes if the condition is progressive or stable, if it is an acquired or congenital condition. It may include a request for information on any future anticipated medical care. It may also include a request for any medications the person is taking. Documentation that may be required my include x-rays, ASIA scale results, or Modified Ashworth Scale scores.[148]

For amputees, the medical classification stage can often done on site at a sports training facility or competition.[149] Sometimes the health examination may not be done on site because the nature of the amputation could cause not physically visible alterations to the body. This is especially true for lower limb amputees as it relates to how their limbs align with their hips and the effect this has on their spine and how their skull sits on their spine.[111]

Functional classification

Functional classification often involves experts familiar with a person's specific medical disability. If a person has multiple disabilities, they may be evaluated by multiple experts, one for each of their disability types. These multiple types are only disability types covered by the classification rules. For example, if a person applying is blind, is deaf and has an intellectual disability and is seeking classification for a sport for the blind, they will not require experts for intellectual disabilities or deafness as these disabilities are not generally covered by the classification for those sports.[150]

Cerebral palsy sports

One of the standard means of assessing functional classification is the bench test, which is used in swimming, lawn bowls and wheelchair fencing.[147][146][25] Using the Adapted Research Council (MRC) measurements, muscle strength is tested using the bench press for a variety of disabilities a muscle being assessed on a scale of 1 to 5 for people with cerebral palsy and other issues with muscle spasticity. A 1 is for no functional movement of the muscle or where there is no motor coordination. A 2 is for normal muscle movement range not exceeding 25% or where the movement can only take place with great difficult and, even then, very slowly. A 3 is where normal muscle movement range does not exceed 50%. A 4 is when normal muscle movement range does not exceed 75% and or there is slight in-coordination of muscle movement. A 5 is for normal muscle movement.[147][25]

As a general rule, CP1 to CP4 sportspeople attend classification in a wheelchair. Failure to do so could result in them being classified as an ambulatory CP class competitor such as CP5 or CP6, or a related sport specific class.[18]

CP footballers functional classification involves the classifiers observing the footballer practicing their sport specific skills in a non-competitive setting, and then the classifiers observing the player in competition for at least 30 minutes.[151]

Wheelchair sports

One of the standard means of assessing functional classification is the bench test, which is used in swimming, lawn bowls and wheelchair fencing.[146][147][25] Using the Adapted Research Council (MRC) measurements, muscle strength is tested using the bench press for a variety of spinal cord related injuries with a muscle being assessed on a scale of 0 to 5. A 0 is for no muscle contraction. A 1 is for a flicker or trace of contraction in a muscle. A 2 is for active movement in a muscle with gravity eliminated. A 3 is for movement against gravity. A 4 is for active movement against gravity with some resistance. A 5 is for normal muscle movement.[147]

Wheelchair fencing classification has 6 test for functionality during classification, along with a bench test. Each test gives 0 to 3 points. A 0 is for no function. A 1 is for minimum movement. A 2 is for fair movement but weak execution. A 3 is for normal execution. The first test is an extension of the dorsal musculature. The second test is for lateral balance of the upper limbs. The third test measures trunk extension of the lumbar muscles. The fourth test measures lateral balance while holding a weapon. The fifth test measures the trunk movement in a position between that recorded in tests one and three, and tests two and four. The sixth test measures the trunk extension involving the lumbar and dorsal muscles while leaning forward at a 45 degree angle. In addition, a bench test is required to be performed.[25]

Electric wheelchair hockey's functional classification test includes cone navigation, hitting and slalom.[53]

Intellectual disability sports

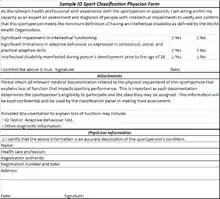

INAS classification is a two step process on the international level. The first step is to contact INAS in coordination with the national sports federation to determine if the person meets minimum eligibility requirements.[152][153][110] Sportspeople can either be directed to provide more evidence of an intellectual disability, rejected outright by INAS or referred to sport specific classifiers.[110] Tests that are eligible to document the disability include Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales, Raven Progressive Matrices, Stanford Binet, Wechsler Intelligence Scales, ABAS Adaptive Behavior Scales, AAMR Adaptive Behaviour Scales, HAWIE, SSAIS and MAWIE.[154] In Australia, documents that may be submitted in support of classification include documentation of attending a specialized school for people with intellectual disabilities, an IQ test conducted by a psychologist or specialist who works with people with intellectual disabilities, or getting government assistance because of their disability.[153] In New Zealand, documentation may include evidence that students are part of Ongoing Resourcing Scheme because of their intellectual disability.[155]

After this is done, a second step is done involving sport specific classification by technical experts familiar with the sport. Cognitive and sport specific tests are conducted to determine if minimum eligible requirements are met.[152][153] Their participation eligibility is either then confirmed or rejected.[110] Sportspeople can be classified as Provisional International Eligibility, which allows them to compete internationally in development events. They can also be classified as Full Primary Eligibility. This allows them to participate in all INAS sanction international events The third eligibility class is Sport Specific Classification. This classification is required for participation at the Paralympic Games.[153] The third eligibility type is governed by the sport specific organization, while the first two are handled by INAS.[153]

Part of the sport specific testing for includes the Sport Cognition Test Battery. This involves psychometric tests that can be administered non-verbally using large touchscreen computers and are sometimes coupled with other tests conducted without a computer at a desk.[110] This is then coupled with TSAL-Q, a questionnaire that explains total time training and experience with the sport. It also includes in competition observation. In swimming, after the competition, the race will likely be reviewed using video analysis to look at stroke speed in the pool.[110] This information is then compared to create a sportsperson profile which is compared to a baseline of non-disabled sportspeople to determine Paralympic eligibility.[110]

Swimming uses a number of sport specific tests for eligibility. The Corsi test is one. It tests memory capacity, with a cut-off score of 6.69. The Tower of London test is used to check executive function. It has a cut-off score of 12.43. Block design is used for visual spatial ability, with a cut-off score of 58.31.[110]

Part of sport specific classification for athletics is a pacing test.[113] Sport specific classification is handled internationally by classifiers from the International Table Tennis Federation.[156] In table tennis, players are asked to demonstrate several types of serves as part of sport specific testing.[113]

Eligibility and class assignment

The final stage of classification is having eligibility determined and then being put into a class.[2] There are several status and classes, of which one is "Ineligible".[2] Other classification statuses include New, Review, Confirmed, and Fixed Review Date.[52] Following being put into a class or being ruled ineligible, the next step is to inform the sportsperson of this decision.[2][52] Another potential status is Non-Cooperative. This occurs when the sportsperson did not, according to the Classification Panel, cooperate during the classification process. When this occurs, sportspeople need to wait three or more months before being eligible to apply for classification again.[2][52] If a sportsperson is determined to be eligible for more than one class in the same sport, the sportsperson must make a decision as to which class they want to compete in as they cannot be classified into two different classes in the same sport at the same time.[150] They may opt to change classes at the end of the sporting season or at after the Paralympic Games depending on the rules for the sport.[150]

If during this process, the Classification Panel determines that the sportsperson or personnel around the sportsperson attempted to manipulate classification results to get an incorrect and beneficial class assignment, the sportsperson could be banned from participating in the sport for two or more years. They may also be required to pay a fine. Support personal cheating classification for sportspeople are also subject to sanction and fines.[2][52]

Protests and appeals

An important component of the classification process is protests regarding classification assignment and eligibility, and the process to appeal these decisions.[2][52] IFs and ISFs are expected to have the procedure for protesting and appealing written into their classification process if they are signatories to the IPC Classification Code.[2] Protests involve the class for which a person is assigned. An appeal is a procedural objection to actions taken during the classification process. Protests go to the governing body for that classification. For example, cycling classification protests would be submitted to the UCI.[2][52] Sportsperson confidentiality is to be insured so that the public is not aware of who has protests someone's classification or appealed their own classification until after a decision has been made.[2]

Protests made need to be submitted by a sportsperson's national federation.[52]

People involved

Beyond the sportspeople getting classified, there are a number of parties involved with the classification process. They include classifiers, head classifier, chief classifier, the classification panel and the classification committee.[2][25] The need for these people is spelled out by the IPC Classification Code.[2]

Classifiers

Classifiers play a critical role in the classification process. Their role is to ensure that sportspeople are placed into the correct class.[157]

In general, a classifier is trained specifically to classify by an ISF or disability type sporting organization to determine a sportsperson's class and classification status. Their skill sets often include medical knowledge, sport specific knowledge and other technical qualifications. They go through a certification process to demonstrate competency as a classifier, generally first on a national level before moving on to international classification.[2][52][25]

Head of Classification

Each ISF and IF has a Head of Classification. The person in this role is responsible for direction, administration, co-ordination and implementation of classification for their sport organization.[2][52]

Chief Classifier

A Chief Classifier is appointed to handle each event. As it relates to the event, their role is similar to that of Head of Classification. They are in charge direction, administration, co-ordination and implementation of classification during that sporting event.[2] If a sportsperson misses their classification procedure or is non-cooperative, it is up to the Chief Classifier to determine if the sportsperson had a valid reason and to reschedule their classification if they accept said reason.[2][52]

Classification Panel

During the classification process, sportspeople deal with multiple classifiers who are assessing different things. Following their assessment, this panel, appointed by the ISF or the IF, gets together to discuss which class a sportsperson should be put into and what their classification status should be.[2][52][25] Each panel requires a minimum of two members.[2] Some sports designate that at least one member be a medical classifier and at least one member be a technical classifier.[52]

Classification Committee

Most ISFs or disability type sporting organization have a classification committee. This committee deals with a number of things, including assessing the latest research related to classification, examining their classification criteria against the latest research and reports from the field, appointing classifiers, keeping a master list of all sportspeople's classification and classification status, liaise with all relevant parties, insuring all private medical information and other data remains secure, organizing classifier training, and otherwise overseeing the classification system.[25]

References

- "Introduction to Classification in Sport". International Bowls for the Disabled. International Bowls for the Disabled. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- IPC Classification Code and International Standards (PDF). International Paralympic Committee. November 2007.

- Chapter 4.4 - Position Statement on background and scientific rationale for classification in Paralympic sport (PDF). International Paralympic Committee. December 2009.

- "장애인e스포츠 활성화를 위한 스포츠 등급분류 연구" [Activate e-sports for people with disabilities: Sports Classification Study] (PDF) (in Korean). KOCCA. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-17.

- "ISMWSF History". Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Retrieved 2016-07-29.

- DeLisa, Joel A.; Gans, Bruce M.; Walsh, Nicholas E. (2005-01-01). Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: Principles and Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781741309.

- Pasquina, Paul F.; Cooper, Rory A. (2009-01-01). Care of the Combat Amputee. Government Printing Office. ISBN 9780160840777.

- Stichting Roeivalidatie (1991). International Symposium Adaptive Rowing Amsterdam June, 26-27 1991. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Stichting Roeivalidatie. p. 18. OCLC 221080358.

- Stichting Roeivalidatie (1991). International Symposium Adaptive Rowing Amsterdam June, 26-27 1991. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Stichting Roeivalidatie. p. 19. OCLC 221080358.

- Hassani, Hossein; Ghodsi, Mansi; Shadi, Mehran; Noroozi, Siamak; Dyer, Bryce (2015). "An Overview of the Running Performance of Athletes with Lower-Limb Amputation at the Paralympic Games 2004–2012" (PDF). Sports. 3 (2): 103–115. doi:10.3390/sports3020103.

- Stichting Roeivalidatie (1991). International Symposium Adaptive Rowing Amsterdam June, 26-27 1991. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Stichting Roeivalidatie. p. 14. OCLC 221080358.

- Labanowich, Stan; Thiboutot, Armand (2011-01-01). Wheelchairs can jump!: a history of wheelchair basketball : tracing 65 years of extraordinary Paralympic and World Championship performances. Boston, MA.: Acanthus Publishing. ISBN 9780984217397. OCLC 792945375.

- DePauw, Karen P; Gavron, Susan J (1995). Disability and sport. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. p. 122. ISBN 978-0873228480. OCLC 31710003.

- Doll-Tepper, Gudrun; Kröner, Michael; Sonnenschein, Werner; International Paralympic Committee, Sport Science Committee (2001). "Organisation and Administration of the Classification Process for the Paralympics". New Horizons in sport for athletes with a disability : proceedings of the International VISTA '99 Conference, Cologne, Germany, 28 August-1 September 1999. Vol. 1. Oxford (UK): Meyer & Meyer Sport. pp. 355–368. ISBN 978-1841260365. OCLC 48404898.

- Clair, Jill M. Le (2013-09-13). Disability in the Global Sport Arena: A Sporting Chance. Routledge. ISBN 9781135694241.

- Brittain, Ian (2016-07-01). The Paralympic Games Explained: Second Edition. Routledge. ISBN 9781317404156.

- Wu, Sheng Kuang (1999). Development of a classification model in disability sport (PhD Thesis). Loughborough, England: Loughborough University.

- Cashman, Richmard; Darcy, Simon (2008-01-01). Benchmark Games. Benchmark Games. ISBN 9781876718053.

- Houlihan, Barrie; Malcolm, Dominic (2015-11-16). Sport and Society: A Student Introduction. SAGE. ISBN 9781473943230.

- Cerebral Palsy-International Sports and Recreation Association (1983). Classification and sport rules manual (Third ed.). Wolfheze, the Netherlands: CP-ISRA. p. 1. OCLC 220878468.

- Cerebral Palsy-International Sports and Recreation Association (1983). Classification and sport rules manual (Third ed.). Wolfheze, the Netherlands: CP-ISRA. pp. 4–6. OCLC 220878468.

- Bailey, Steve (2008-02-28). Athlete First: A History of the Paralympic Movement. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470724316.

- Cerebral Palsy-International Sports and Recreation Association (1983). Classification and sport rules manual (Third ed.). Wolfheze, the Netherlands: CP-ISRA. pp. 7–8. OCLC 220878468.

- Whyte, Gregory; Loosemore, Mike; Williams, Clyde (2015-07-27). ABC of Sports and Exercise Medicine. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118777503.

- "IWF Rules for Competition, Book 4 – Classification Rules" (PDF). IWAS. 20 March 2011.

- Howe, P. David; Jones, Carwyn (2006). "Classification of Disabled Athletes: (Dis)Empowering the Paralympic Practice Community". Sociology of Sport Journal. 23: 29–46. doi:10.1123/ssj.23.1.29.

- Tweedy, Sean M. (2002). "Taxonomic Theory and the ICF: Foundations for a Unified Disability Athletics Classification". Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly. 19 (2): 220–237. doi:10.1123/apaq.19.2.220. PMID 28195770.

- Stichting Roeivalidatie (1991). International Symposium Adaptive Rowing Amsterdam June, 26-27 1991. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Stichting Roeivalidatie. p. 16. OCLC 221080358.

- Stichting Roeivalidatie (1991). International Symposium Adaptive Rowing Amsterdam June, 26-27 1991. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Stichting Roeivalidatie. p. 5. OCLC 221080358.

- Stichting Roeivalidatie (1991). International Symposium Adaptive Rowing Amsterdam June, 26-27 1991. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Stichting Roeivalidatie. p. 21. OCLC 221080358.

- Stichting Roeivalidatie (1991). International Symposium Adaptive Rowing Amsterdam June, 26-27 1991. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Stichting Roeivalidatie. p. 22. OCLC 221080358.

- DePauw, Karen P; Gavron, Susan J (1995). Disability and sport. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. p. 43. ISBN 978-0873228480. OCLC 31710003.

- "Classification 101". Blaze Sports. Blaze Sports. June 2012. Archived from the original on August 16, 2016. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- "IWAS transfer governance of Wheelchair Rugby to IWRF". Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Retrieved 2019-06-12.

- Doll-Tepper, Gudrun; Kröner, Michael; Sonnenschein, Werner; International Paralympic Committee, Sport Science Committee (2001). "Organisation and Administration of the Classification Process for the Paralympics". New Horizons in sport for athletes with a disability : proceedings of the International VISTA '99 Conference, Cologne, Germany, 28 August-1 September 1999. Vol. 1. Oxford (UK): Meyer & Meyer Sport. p. 290. ISBN 978-1841260365. OCLC 48404898.

- Hores Extraordinaries, S.A. (1992). Guide to the Barcelona'92 IX Paralympic Games. Barcelona: COOB'92, Paralympics Division D.L. p. 46. ISBN 978-8478682331. OCLC 433443804.