Electoral threshold

The electoral threshold, or election threshold, is the minimum share of all the votes cast that a candidate or political party requires to achieve before they become entitled to representation or additional seats in a legislature. This limit can operate in various ways, e.g. in party-list proportional representation systems where an electoral threshold requires that a party must receive a specified minimum percentage of votes (e.g. 5%), either nationally or in a particular electoral district, to obtain seats in the legislature. In single transferable voting, the election threshold is called the quota and it is possible to pass it by use of first choice votes alone or by a combination of first choice votes and votes transferred from other candidates based on lower preferences (and in the last resort to fill the target number of seats, it is possible to be elected under STV even if a candidate does not pass the election threshold). In mixed-member-proportional (MMP) systems the election threshold determines which parties are eligible for top-up seats in the legislative body (but some MMP system still allow a party to retain the seat they won in their electoral district even when they did not receive the threshold nationally).

| Part of the Politics series |

| Voting |

|---|

|

|

The effect of this electoral threshold is to deny representation to small parties or to force them into coalitions, with the presumption of rendering the election system more stable by keeping out fringe parties. Proponents say that simply having a few seats in a legislature can significantly boost the profile of a fringe party and that providing representation and possibly veto power for a party that receives only 1 percent of the vote is not appropriate.[1] However, others argue that in the absence of a ranked ballot or other proportional systems, supporters of minor parties are effectively disenfranchised when barred from the top-up seats and are denied the right to be represented by someone of their choosing.

Two boundaries can be defined—a threshold of representation is the minimum vote share that might yield a party a seat under the most favorable circumstances for the party, while the threshold of exclusion is the maximum vote share that could be insufficient to yield a seat under the least favorable circumstances. Arend Lijphart suggested calculating the informal threshold as the mean of these.[2]

The electoral threshold is a barrier to entry for political parties to the political competition.[3]

Recommendations for electoral thresholds

The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe recommends for parliamentary elections a threshold not higher than three percent.[4] For single transferable vote, to put the natural threshold at about ten percent, John M. Carey and Simon Hix recommend a low district magnitude of approximately six.[5][6] Most STV systems used today set the number of votes for the election of most members at the Droop quota, which in a six-member district is 14 percent.

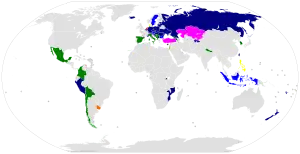

Electoral thresholds in various countries

Note that some countries may have more rules for coalitions and independents and for winning a specific number of district seats

In Poland's Sejm, Lithuania's Seimas, Germany's Bundestag and New Zealand's House of Representatives, the threshold is 5 percent (in Poland, additionally 8 percent for a coalition of two or more parties submitting a joint electoral list and in Lithuania, additionally 7 percent for coalition). However, in New Zealand, if a party wins a directly elected seat, the threshold does not apply.

The threshold is 3.25 percent in Israel's Knesset (it was 1% before 1992, 1.5% from 1992 to 2003 and 2% form 2003 to 2014) and 7 percent in the Turkish parliament. In Poland, ethnic minority parties do not have to reach the threshold level to get into the parliament and so there is always a small German minority representation (at minimum, one member) in the Sejm. In Romania, for the ethnic minority parties there is a different threshold than for the national parties that run for the Chamber of Deputies.

There are also countries such as Portugal, South Africa, Finland, the Netherlands and North Macedonia that have proportional representation systems without a legal threshold, although the Netherlands has a rule that the first seat can never be a remainder seat, which means that there is an effective threshold of 100 percent divided by the total number of seats (with 150 seats to allocate, this threshold is currently 0.67%).

Australia

The Senate of Australia is elected using single transferable vote (STV) and does not use an electoral threshold or have a predictable "natural" or "hidden" threshold. At a normal election, each state returns six senators and the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory each return two. (For the states, the number is doubled in a double dissolution election.) As such, the quota for election (as determined through the Droop quota) is 14.3 percent or 33.3 percent respectively. (For the states, the quota for election is halved in a double dissolution election.) However, as STV is a ranked voting system, candidates who receive less than the quota for election in primary votes can still end up being elected if they amass sufficient preferences to reach the Droop quota. Therefore, the sixth (or, at a double dissolution election, the 12th) Senate seat in each state is often won by a party that received considerably less than the Droop quota in primary votes. For example, at the 2022 election, the sixth Senate seat in Victoria was won by the United Australia Party even though it won only 4 percent of the primary vote in that state.

Germany

Germany, has a regular threshold of 5 percent, and ethnic minority parties have no threshold.[7] The 2021 election demonstrated the exception for ethnic minority party: the South Schleswig Voters' Association entered the Bundestag with just 0.1 percent as a registered party for Danish and Frisian minorities. The exception to the 5 percent electoral threshold by winning three constituency seats has been repealed in 2023. That exception allowed the Left to qualify for list votes despite getting just 4.9 percent.

Norway

In Norway, the nationwide electoral threshold of 4 percent applies only to leveling seats. A party with sufficient local support may still win the regular district seats, even if the party fails to meet the threshold. For example, the 2021 election saw the Green Party and Christian Democratic Party each win three district seats, and Patient Focus winning one district seat despite missing the threshold.

Slovenia

In Slovenia, the threshold was set at 3 parliamentary seats during parliamentary elections in 1992 and 1996. This meant that the parties needed to win about 3.2 percent of the votes in order to pass the threshold. In 2000, the threshold was raised to 4 percent of the votes.

Sweden

In Sweden, there is a nationwide threshold of 4 percent for the Riksdag, but if a party reaches 12 percent in any electoral constituency, it will take part in the seat allocation for that constituency.[8] As of the 2022 election, nobody has been elected based on the 12 percent rule.

United States

In the United States, as the majority of elections are conducted under the first-past-the-post system, legal electoral thresholds do not apply in the actual voting. However, several states have threshold requirements for parties to obtain automatic ballot access to the next general election without having to submit voter-signed petitions. The threshold requirements have no practical bearing on the two main political parties (the Republican and Democratic parties) as they easily meet the requirements, but have come into play for minor parties such as the Green and Libertarian parties. The threshold rules also apply for independent candidates to obtain ballot access.

List of electoral thresholds by country

Europe

| Country | Lower (or sole) house | Upper house | Other elections | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For individual parties | For other types | Other threshold | |||

| Albania | 3% | 5% for multi-party alliances to each electoral area level[9] | |||

| Andorra | 7.14% (1⁄14 of votes cast)[10] | ||||

| Armenia | 5% | 7% for multi-party alliances | |||

| Austria | 4% | 0% for ethnic minorities | |||

| Belgium | 5% (at constituency level; no national threshold) | ||||

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 3% (at constituency level; no national threshold) | ||||

| Bulgaria | 4% | ||||

| Croatia | 5% (at constituency level; no national threshold) | ||||

| Cyprus | 3.6% | ||||

| Czech Republic | 5% | 8% for bipartite alliances, 11% for multi-party alliances; does not apply for EU elections | |||

| Denmark | 2%[11][12] | 1 constituency seat | |||

| Estonia | 5% | ||||

| Finland | None, but high natural threshold due to multiple districts | ||||

| France | Not applicable | 5% in European Parliament elections[13] and in municipal elections for cities with at least 1000 habitants[14][15] | |||

| Germany | 5% | 0% for ethnic minorities | 3 constituency seats | 0% in European Parliament elections | |

| Georgia | 5%[16] | 3% for local elections in all municipalities but Tbilisi (2.5%)[16] | |||

| Greece | 3% | ||||

| Hungary | 5% | 10% for bipartite alliances, 15% for multi-party alliances, 0.26% for ethnic minorities (for the first seat only) | |||

| Ireland | Natural threshold 8 – 12% because 3 to 5 seats in each constituency | ||||

| Iceland | 5% (only for compensatory seats)[17] | ||||

| Italy | 3% | 10% (party alliances), but a list must reach at least 3%, 1% (parties of party alliances), 20% or two constituencies (ethnic minorities) | 3% | ||

| Kosovo | 5% | ||||

| Latvia | 5% | ||||

| Liechtenstein | 8% | ||||

| Lithuania | 5% | 7% for party alliances | |||

| Malta | natural threshold 12% due to district magnitude of 5 | ||||

| Moldova | 5% | 3% (non-party), 12% (party alliances) | |||

| Monaco | 5%[18] | ||||

| Montenegro | 3% | Special rules apply for candidate lists representing national minority communities.[19] | |||

| Netherlands | 0.6̅% (percent of votes needed for one seat; parties failing to reach this threshold have no right to a possible remainder seat)[20] | ||||

| Northern Cyprus | 5% | ||||

| North Macedonia | None, but high natural threshold due to multiple districts | ||||

| Norway | 4% (only for compensatory seats) | ||||

| Poland | 5% | 8% (alliances; does not apply for EU elections); 0% (ethnic minorities) | |||

| Portugal | None, but high natural threshold due to multiple districts | ||||

| Romania | 5% | 10% (alliances) | |||

| Russia | 5% | ||||

| San Marino | 5%[21] | ||||

| Scotland | 5% | ||||

| Spain | 3% (constituency). Ceuta and Melilla use first-past-the-post system. | None | 5% for local elections. Variable in regional elections. | ||

| Sweden | 4% (national level) 12% (constituency) | ||||

| Switzerland | None, but high natural threshold in some electoral districts | ||||

| Serbia | 3%[22] | 0% for ethnic minorities[23][22] | |||

| Slovakia | 5% | 7% for bi- and tri-partite alliances, 10% for 4- or more-party alliances[24] | |||

| Slovenia | 4% | ||||

| Turkey | 7%[25] | 7% for multi-party alliances. Parties in an alliance not being subject to any nationwide threshold individually. No threshold for independent candidates. | |||

| Ukraine | 5%[26] | ||||

| Wales | 5% | ||||

The electoral threshold for elections to the European Parliament varies for each member state, a threshold of up to 5 percent is applied for individual electoral districts, no threshold is applied across the whole legislative body.[27]

Non-European countries

| Country | Lower (or sole) house | Upper house | Other elections | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For individual parties | For other types | Other threshold | |||

| Argentina | 3% of registered voters[28] | 1.5% of valid votes for primaries | |||

| Australia | Single-member districts for the House of Representatives | ||||

| Bolivia | 3% | ||||

| Brazil | No national electoral threshold, for parties threshold is 80% of the natural threshold in the district; for candidates 20% of the natural threshold in the district.[29][30] | threshold for financial contributions is 2% at constituency level or 11 deputies in 9 states,[31][32][33] increasing 2026 to 2.5% and 2030 to 3% | |||

| Burundi | 2%[34] | ||||

| Chile | None, but high natural threshold due to its use of multiple-member districts with less than 10 seats | ||||

| Colombia | 3% | ||||

| East Timor | 4%[35][36][37] | ||||

| Ecuador | None, but high natural threshold due to its use of multiple-member districts with less than 10 seats | ||||

| Fiji | 5% | ||||

| Indonesia | 4%[38] | ||||

| Israel | 3.25% | ||||

| Kazakhstan | 5% | ||||

| Kyrgyzstan | 5% and 0.5% of the vote in each of the seven regions | ||||

| Lesotho | None, natural threshold ~0.4% | ||||

| Mexico | 3% | ||||

| Mozambique | 5%[39] | ||||

| Nepal | 3% vote each under the proportional representation category and at least one seat under the first-past-the-post voting | ||||

| New Zealand | 5%[40] | 1 constituency seat | |||

| Palestine | 2% | ||||

| Paraguay | None, but high natural threshold due to its use of multiple-member districts with less than 10 seats | ||||

| Peru | 5%[41] | ||||

| Philippines | 2% | Other parties can still qualify if the 20% of the seats have not been filled up. | |||

| Rwanda | 5% | ||||

| South Africa | None, natural threshold ~0.2% | ||||

| South Korea | 3%[42][43] | 5 constituency seats | 5% (local council elections)[44] | ||

| Taiwan | 5%[45] | ||||

| Tajikistan | 5%[46] | ||||

| Thailand | None, natural threshold ~0.1%[47] | ||||

| Uruguay | 1% | 3% | |||

Legal challenges

The German Federal Constitutional Court rejected an electoral threshold for the European Parliament in 2011 and in 2014 based on the principle of one person, one vote.[48] In the case of Turkey, in 2004 the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe declared this threshold to be manifestly excessive and asked Turkey to lower it (Council of Europe Resolution 1380 (2004)). On 30 January 2007 the European Court of Human Rights ruled by five votes to two and on 8 July 2008, its Grand Chamber by 13 votes to four that the former 10 percent threshold imposed in Turkey does not violate the right to free elections (Article 3 of Protocol 1 of the ECHR).[49] It held, however, that this same threshold could violate the Convention if imposed in a different country. It was justified in the case of Turkey in order to stabilize the volatile political situation over recent decades.[50][51]

Natural threshold

The number of seats in each electoral district creates a "hidden" natural threshold (also called an effective, or informal threshold). The number of votes that means that a party is guaranteed a seat can be calculated by the formula () where ε is the smallest possible number of votes. That means that in a district with four seats slightly more than 20 percent of the votes will guarantee a seat. Under more favorable circumstances, the party can still win a seat with fewer votes.[52] The most important factor in determining the natural threshold is the number of seats to be filled by the district. Other factors are the seat allocation formula (Saint-Laguë, D'Hondt or Hare), the number of contestant political parties and the size of the assembly. Generally, smaller districts leads to a higher proportion of votes needed to win a seat and vice versa.[53] The lower bound (the threshold of representation or the percentage of the vote that allows a party to earn a seat under the most favorable circumstances) is more difficult to calculate. In addition to the factors mentioned earlier, the number of votes cast for smaller parties are important. If more votes are cast for parties that do not win any seat, that will mean a lower percentage of votes needed to win a seat.[52]

Notable cases

An extreme example occurred in Turkey following the 2002 Turkish general election, where almost none of the 550 incumbent MPs were returned. This was a seismic shift that rocked Turkish politics to its foundations. None of the political parties that had passed the threshold in 1999, passed it again: DYP received only 9.55 percent of the popular vote, MHP received 8.34 percent, GP 7.25 percent, DEHAP 6.23 percent, ANAP 5.13 percent, SP 2.48 percent and DSP 1.22 percent. The aggregate number of wasted votes was an unprecented 46.33 percent (14,545,438). As a result, Erdoğan's AKP gained power, winning more than two-thirds of the seats in the Parliament with just 34.28 percent of the vote, with only one opposition party (CHP, which by itself failed to pass threshold in 1999) and 9 independents.

Other dramatic events can be produced by the loophole often added in mixed-member proportional representation (used throughout Germany since 1949, New Zealand since 1993): there the threshold rule for party lists includes an exception for parties that won 3 (Germany) or 1 (New Zealand) single-member districts. The party list vote helps calculate the desirable number of MPs for each party. Major parties can help minor ally parties overcome the hurdle, by letting them win one or a few districts:

- 2008 New Zealand general election: While New Zealand First received only 4.07 percent of the list vote (so it was not returned to parliament), ACT New Zealand won 3.65 percent of the list vote, but its leader won an electorate seat (Epsom), which entitled the party to list seats (4). In the 2011 election, leaders of the National Party and ACT had tea together before the press to promote the implicit alliance (see tea tape scandal). After their victories, the Nationals passed a confidence and supply agreement with ACT to form the Fifth National Government of New Zealand.

- In Germany, the post-communist PDS and its successor Die Linke often hovered around the 5 percent threshold: In 1994, it won only 4.4 percent of the party list vote, but won four districts in East Berlin, which saved it, earning 30 MPs in total. In 2002, it achieved only 4.0 percent of the party list vote, and won just two districts, this time excluding the party from proportional representation. This resulted in a narrow red-green majority and a second term for Gerhard Schröder, which would not have been possible had the PDS won a third constituency. In 2021, it won only 4.9 percent of the party list vote, but won the bare minimum of three districts (Berlin-Lichtenberg, Berlin-Treptow-Köpenick, and Leipzig II), salvaging the party, which received 39 MPs.

The failure of one party to reach the threshold not only deprives their candidates of office and their voters of representation; it also changes the power index in the assembly, which may have dramatic implications for coalition-building.

- Slovakia, 2002. The True Slovak National Party (PSNS) split from Slovak National Party (SNS), and Movement for Democracy (HZD) split from the previously dominant People's Party – Movement for a Democratic Slovakia. All of them failed to cross the 5 percent threshold with PSNS having 3.65 percent, SNS 3.33 percent and HZD 3.26 percent respectively, thus allowing a center-right coalition despite having less than 43 percent of the vote.

- Norway, 2009. The Liberal Party received 3.9 percent of the votes, below the 4 percent threshold for leveling seats, although still winning two seats. Hence, while right-wing opposition parties won more votes between them than the parties in the governing coalition, the narrow failure of the Liberal Party to cross the threshold kept the governing coalition in power. It crossed the threshold again at the following election with 5.2 percent.

- In the 2013 German federal election, the FDP, in Parliament since 1949, received only 4.8 percent of the list vote, and won no single district, excluding the party altogether. This, along with the failure of the right-wing eurosceptic party AfD (4.7%), gave a left-wing majority in Parliament despite a center-right majority of votes (CDU/CSU itself fell short of an absolute majority by just 5 seats). As a result, Merkel's CDU/CSU formed a grand coalition with the SPD.

- Poland, 2015. The United Left achieved 7.55 percent, which is below the 8 percent threshold for multi-party coalitions. Furthermore, KORWiN only reached 4.76 percent, narrowly missing the 5 percent threshold for individual parties. This allowed the victorious PiS to obtain a majority of seats with 37 percent of the vote. This was the first parliament without left-wing parties represented.

- Israel, April 2019. Among the 3 lists representing right-wing to far-right Zionism and supportive of Netanyahu, only one crossed the threshold the right-wing government had increased to 3.25 percent: the Union of the Right-Wing Parties with 3.70 percent, while future Prime Minister Bennett's New Right narrowly failed at 3.22 percent, and Zehut only 2.74 percent, destroying Netanyahu's chances of another majority, and leading to snap elections in September.

- Czech Republic, 2021. Přísaha (4.68%), ČSSD (4.65%) and KSČM (3.60%) all failed to cross the 5 percent threshold, thus allowing a coalition of Spolu and PaS. This was also the first time that neither ČSSD nor KSČM had representation in parliament since 1992.

Memorable dramatic losses:

- In the 1990 German federal election, the Western Greens did not meet the threshold, which was applied separately for former East and West Germany. The Greens could not take advantage of this, because the "Alliance 90" (which had absorbed the East German Greens) ran separately from "The Greens" in the West. Together, they would have narrowly passed the 5.0 percent threshold (West: 4.8%, East: 6.2%). The Western Greens returned to the Bundestag in 1994.

- Israel, 1992. The extreme right-wing Tehiya (Revival) received 1.2 percent of the votes, which was below the threshold which it had itself voted to raise to 1.5 percent. It thus lost its three seats.

- In Bulgaria, the so-called "blue parties"[54] or "urban right"[55] which include SDS, DSB, Yes, Bulgaria!, DBG, ENP and Blue Unity frequently get just above or below the electoral threshold depending on formation of electoral alliances: In the EP election 2007, DSB (4.74%) and SDS (4.35%) were campaigning separately and both fell below the natural electoral of around 5 percent. In 2009 Bulgarian parliamentary election, DSB and SDS ran together as Blue Coalition gaining 6.76 percent. In 2013 Bulgarian parliamentary election, campaigning separately DGB received 3.25 percent, DSB 2.93 percent, SDS 1.37 percent and ENP 0.17 percent, thus all of them failed to cross the threshold this even led to a tie between the former opposition and the parties right of the centre. In the EP election 2014, SDS, DSB and DBG ran as Reformist Bloc gaining 6.45 percent and crossing the electoral threshold, while Blue Unity campaigned separately and did not cross the electoral threshold. In 2017 Bulgarian parliamentary election, SDS and DBG ran as Reformist Bloc gaining 3.06 percent, "Yes, Bulgaria!" received 2.88 percent, DSB 2.48 percent, thus all of them failed to cross the electoral threshold. In the EP election 2019, "Yes, Bulgaria!" and DBG ran together as Democratic Bulgaria and crossed the electoral threshold with 5.88 percent. In November 2021, electoral alliance Democratic Bulgaria crossed electoral threshold with 6.28 percent.

- Slovakia, 2010. Both the Party of the Hungarian Community which (including their predecessors) hold seats in parliament since the Velvet Revolution and the People's Party – Movement for a Democratic Slovakia, which dominated in the 1990s, received 4.33 percent and thus failed to achieve the 5 percent threshold.

- Slovakia, 2016. The Christian Democratic Movement achieved 4.94 percent missing only 0.06 percent votes to reach the threshold which meant the first absence of the party since the Velvet Revolution and the first democratic elections in 1990.

- Slovakia, 2020. The coalition between Progressive Slovakia and SPOLU won 6.96 percent of votes, falling only 0.04 percent short of the 7 percent threshold for coalitions. This was an unexpected defeat since the coalition had won seats in the 2019 European election and won the 2019 presidential election less than a year earlier. In addition, two other parties won fewer votes but were able to win seats due to the lower threshold for single parties (5%). This was also the first election since the Velvet Revolution in which no party of the Hungarian minority crossed the 5 percent threshold.

- Lithuania, 2020. The LLRA–KŠS won only 4.80 percent of the party list votes.

- Madrid, Spain, 2021. Despite achieving 26 seats with 19.37 percent of the votes in the previous election, the liberal Ciudadanos party crashed down to just 3.54 percent in the 2021 snap election called by Isabel Díaz Ayuso, failing to get close to the 5 percent threshold.

- Slovenia, 2022. Democratic Party of Pensioners of Slovenia only achieved 0.62 percent of the vote. This was the first time when DeSUS did not reached the 4 percent since 1996 which was part of almost every coalition since its foundation.

- Germany, 2022 Saarland state election. Alliance 90/The Greens fell 23 votes or 0.005 percent short of reaching representation. The Left fell from 12.8 percent to below the electoral threshold with 2.6 percent in their only western stronghold. Total percentage of votes not represented was 22.3 percent.[56]

- Israel, 2022 Israeli legislative election. Meretz fell to 3.16 percent thus failed to cross the threshold for the first time.

There has been cases of tries to attempts to circumvent thresholds:

- Slovakia, 1998. Slovak Democratic Coalition ran as political party because the threshold was 25 percent.

- Turkey, 2007 and 2011. The DTP/BDP-led Thousand Hope Candidates and Labour, Democracy and Freedom Bloc only gained 3.81 percent (2007) and 5.67 percent (2011) of the vote not crossing the 10 percent threshold but because they ran as independents they won 22 and 36 seats.

- Poland, 2019. After the United Left and KORWiN failed to cross the thresholds in 2015 both of them with their new alliances bypassed the coalition threshold by either running under SLD label (Lewica) or registering their alliance as a party itself (Confederation). Similarly to Lewica, the Polish Coalition ran under Polish People's Party label. Lewica and Polish Coalition would have crossed the coalition threshold of 8 percent with 12.56 percent and 8.55 percent respectively while Confederation only gained 6.81 percent of the vote.

- Czechia, 2021. The Tricolour–Svobodní–Soukromníci alliance tried to bypass the coalition threshold by renaming Tricolour to include the names of their partners but they only received 2.76 percent, failing to cross the usual 5 percent threshold.

Amount of wasted vote

Electoral thresholds can sometimes seriously affect the relationship between the percentages of the popular vote achieved by each party and the distribution of seats. The proportionality between seat share and popular vote can be measured by the Gallagher index while the amount of wasted votes is a measure of the total number of voters not represented by any party sitting in the legislature.

The failure of one party to reach the threshold not only deprives their candidates of office and their voters of representation; it also changes the power index in the assembly, which may have dramatic implications for coalition-building.

The amount of wasted vote changes from one election to another, here shown for New Zealand.[57] The wasted vote changes depending on voter behavior and size of effective electoral threshold,[58] for example in 2005 New Zealand general election every party above 1 percent received seats due to the electoral threshold in New Zealand of at least one seat in first-past-the-post voting, which caused a much lower wasted vote compared to the other years.

In the Russian parliamentary elections in 1995, with a threshold excluding parties under 5 percent, more than 45 percent of votes went to parties that failed to reach the threshold. In 1998, the Russian Constitutional Court found the threshold legal, taking into account limits in its use.[59]

After the first implementation of the threshold in Poland in 1993 34.4 percent of the popular vote did not gain representation.

There had been a similar situation in Turkey, which had a 10 percent threshold, easily higher than in any other country.[60] The justification for such a high threshold was to prevent multi-party coalitions and put a stop to the endless fragmentation of political parties seen in the 1960s and 1970s. However, coalitions ruled between 1991 and 2002, but mainstream parties continued to be fragmented and in the 2002 elections as many as 45 percent of votes were cast for parties which failed to reach the threshold and were thus unrepresented in the parliament.[61] All parties which won seats in 1999 failed to cross the threshold, thus giving Justice and Development Party 66 percent of the seats.

In the Ukrainian elections of March 2006, for which there was a threshold of 3 percent (of the overall vote, i.e. including invalid votes), 22 percent of voters were effectively disenfranchised, having voted for minor candidates. In the parliamentary election held under the same system, fewer voters supported minor parties and the total percentage of disenfranchised voters fell to about 12 percent.

In Bulgaria, 24 percent of voters cast their ballots for parties that would not gain representation in the elections of 1991 and 2013.

In the 2020 Slovak parliamentary election, 28.47 percent of all valid votes did not gain representation.[62] In the 2021 Czech legislative election 19.76 percent of voters were not represented.[63] In the 2022 Slovenian parliamentary election 24 percent of the vote went to parties which did not reach the 4 percent threshold including several former parliamentary parties (LMŠ, PoS, SAB, SNS and DeSUS).

In the Philippines where party-list seats are only contested in 20 percent of the 287 seats in the lower house, the effect of the 2 percent threshold is increased by the large number of parties participating in the election, which means that the threshold is harder to reach. This led to a quarter of valid votes being wasted, on average and led to the 20 percent of the seats never being allocated due to the 3-seat cap In 2007, the 2 percent threshold was altered to allow parties with less than 1 percent of first preferences to receive a seat each and the proportion of wasted votes reduced slightly to 21 percent, but it again increased to 29 percent in 2010 due to an increase in number of participating parties. These statistics take no account of the wasted votes for a party which is entitled to more than three seats but cannot claim those seats due to the three-seat cap.

Electoral thresholds can produce a spoiler effect, similar to that in the first-past-the-post voting system, in which minor parties unable to reach the threshold take votes away from other parties with similar ideologies. Fledgling parties in these systems often find themselves in a vicious circle: if a party is perceived as having no chance of meeting the threshold, it often cannot gain popular support; and if the party cannot gain popular support, it will continue to have little or no chance of meeting the threshold. As well as acting against extremist parties, it may also adversely affect moderate parties if the political climate becomes polarized between two major parties at opposite ends of the political spectrum. In such a scenario, moderate voters may abandon their preferred party in favour of a more popular party in the hope of keeping the even less desirable alternative out of power.

On occasion, electoral thresholds have resulted in a party winning an outright majority of seats without winning an outright majority of votes, the sort of outcome that a proportional voting system is supposed to prevent. For instance, the Turkish AKP won a majority of seats with less than 50 percent of votes in three consecutive elections (2002, 2007 and 2011). In the 2013 Bavarian state election, the Christian Social Union failed to obtain a majority of votes, but nevertheless won an outright majority of seats due to a record number of votes for parties which failed to reach the threshold, including the Free Democratic Party (the CSU's coalition partner in the previous state parliament). In Germany in 2013 15.7 percent voted for a party that did not meet the 5 percent threshold.

In contrast, elections that use the ranked voting system can take account of each voter's complete indicated ranking preference. For example, the single transferable vote redistributes first preference votes for candidates below the threshold. This permits the continued participation in the election by those whose votes would otherwise be wasted. Minor parties can indicate to their supporters before the vote how they would wish to see their votes transferred. The single transferable vote is a proportional voting system designed to achieve proportional representation through ranked voting in multi-seat (as opposed to single seat) organizations or constituencies (voting districts).[64] Ranked voting systems are widely used in Australia and Ireland. Other methods of introducing ordinality into an electoral system can have similar effects.

Notes

- Reynolds, Andrew (2005). Electoral system design : the new international IDEA handbook. Stockholm, Sweden: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. p. 59. ISBN 978-91-85391-18-9. OCLC 68966125.

- Arend Lijphart (1994), Electoral Systems and Party Systems: A Study of Twenty-Seven Democracies, 1945–1990. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 25–56

- Tullock, Gordon. "Entry barriers in politics." The American Economic Review 55.1/2 (1965): 458-466.

- Resolution 1547 (2007), para. 58

- Carey and Hix, The Electoral Sweet Spot, p. 7

- Carey, John M.; Hix, Simon (2011). "The Electoral Sweet Spot: Low-Magnitude Proportional Electoral Systems" (PDF). American Journal of Political Science. 55 (2): 383–397. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00495.x.

- "Germany passes law to shrink its XXL parliamen". Deutsche Welle.

- Swedish Election Authority. "Elections in Sweden The way it's done!" (PDF). p. 13.

- The Electoral Code of the Republic of Albania Archived 31 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Artikel 162; vor der Wahl 2009 waren es bei völlig anderem Wahlsystem 2,5% bzw. 4% der gültigen Stimmen auf nationaler Ebene (nur für die Vergabe von Ausgleichssitzen; Direktmandate wurden ohne weitere Bedingungen an den stimmenstärksten Kandidaten zugeteilt)

- OSCE (19 February 2020). "PRINCIPALITY OF ANDORRA PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS 7 April 2019 ODIHR Needs Assessment Mission Report". Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- "Folketingsvalgloven". Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- Bille, Lars; Pedersen, Karina (2004). "Electoral Fortunes and Responses of the Social Democratic Party and Liberal Party in Denmark: Ups and Downs". In Mair, Peter; Müller, Wolfgang C.; Plasser, Fritz (eds.). Political parties and electoral change. SAGE Publications. p. 207. ISBN 0-7619-4719-1.

- "Projet de loi relatif à l'élection des représentants au Parlement européen (INTX1733528L)". Légifrance. 3 January 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- "Les municipales, une élection pour profs de maths". Slate FR. 30 March 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- "Quel est le mode de scrutin pour les élections municipales dans les communes de 1 000 habitants et plus ?". Vie Publique. 9 February 2021. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- "Election code of Georgia". Legislative Herald of Georgia. 27 December 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- , Election to Altthingi Law, Act no. 24/2000, Article 108

- "Election Profile". IFES. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- "These rules apply to lists representing a minority nation or a minority national community with a share of the total population of up to 15 per cent countrywide or 1.5 to 15 per cent within each municipality. If no minority list passes the 3 per cent threshold, but some lists gain 0.7 per cent or more of the valid votes, they are entitled to participate in the distribution of up to 3 mandates as a cumulative list of candidates based on the total number of valid votes. Candidate lists representing the Croatian minority are entitled to 1 seat if they obtain at least 0.35 per cent of the valid votes." Source: OSCE, 2016, Montenegro Parliamentary Elections 2016: OSCE/ODIHR Election Observation Mission Final Report

- "Who can vote and for whom? How the Dutch electoral system works". DutchNews.nl. 30 January 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- "OSCE report on 2019 parliamentary elections".

- "Parliament agrees to 3% electoral threshold". Serbian Monitor. 10 February 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- OSCE. "REPUBLIC OF SERBIA PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS Spring 2020 ODIHR Needs Assessment Mission Report".

- Slovak law number 180/2014 § 66, in Slovak

- "Turkey lowers national threshold to 7% with new election law". Daily Sabah. 31 March 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- Electoral Code becomes effective in Ukraine

- The European Parliament: electoral procedures

- Código Electoral Nacional, Article 160

- New rule complicates distribution of vacancies of Deputies, Jairus Nicholas May 3,2022

- Brazil Law No. 14,211, of October 1, 2021

- Oliveira, José Carlos (30 June 2018). "Eleições deste ano trazem cláusulas de desempenho para candidatos e partidos". Chamber of Deputies of Brazil (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- "Sem votação mínima, 14 partidos ficarão sem recursos públicos". R7 (in Brazilian Portuguese). 9 October 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- "Com dura cláusula de barreira, metade das siglas corre risco de acabar". O Tempo (in Brazilian Portuguese). 12 July 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- Electoral system IPU

- Electoral system Inter-Parliamentary Union

- Fourth amendment to the Law on Election of the National Parliament. Article 13.2

- Timor Agora: PN APROVA BAREIRA ELEISAUN PARLAMENTAR 4%, 13 February 2017, retrieved 23 March 2017.

- "New election bill, new hope for democracy".

- Electoral system IPU

- Electoral Commission: What is MMP?

- "Peru's small political parties scramble to survive". April 2016.

- "국가법령정보센터".

- 공직선거법 제189조 제1항(The first clause of Article 189 of the Public Official Election Act)

- 공직선거법 제190조의2 제1항(The first clause of Article 190-2 of the Public Official Election Act)

- "Legislative Yuan Elections – Central Election Commission". Archived from the original on 9 April 2014. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- "Tajikistan ruling party to win polls, initial count shows". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- "Thailand's New Electoral System". 21 March 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- "Karlsruhe vs. EU electoral reform could go into the third round". EURACTIV MEDIA NETWORK BV. 18 May 2022.(in German)

- Turkish Daily News, 31 January 2007, European court rules election threshold not violation

- Yumak and Sadak v. Turkey, no. 10226/03.

- Negating Pluralist Democracy: The European Court of Human Rights Forgets the Rights of the Electors, KHRP Legal Review 11 (2007)

- "Report on Thresholds and other features of electoral systems which bar parties from access to Parliament (II)". venice.coe.int. 2010. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- "Report on Thresholds and other features of electoral systems which bar parties from access to Parliament". venice.coe.int. 2008. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- "Prowestliche Parteien sind Bulgariens große Wahlverlierer". Weser-Kurier. 28 March 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- "Bulgaria election: All you need to know about country's fourth vote in just 18 months Access to the comments". Euronews. 2 October 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- "Results 2022 Saarland state election". German State Statistical Officer.(in German)

- "2020 GENERAL ELECTION – OFFICIAL RESULTS AND STATISTICS". ElectionResults.govt.nz. Electoral Commission. 30 November 2020.

- Chang, Eric C.C.; Higashijima, Masaaki (2023). "The Choice of Electoral Systems in Electoral Autocracies". Government and Opposition. 58: 106–128. doi:10.1017/gov.2021.17. S2CID 235667437.

- Постановление Конституционного Суда РФ от 17 ноября 1998 г. № 26-П – см. пкт. 8(in Russian) Archived 21 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Toker, Cem (2008). "Why Is Turkey Bogged Down?" (PDF). Turkish Policy Quarterly. Turkish Policy. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- In 2004 the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe declared this threshold to be manifestly excessive and invited Turkey to lower it (Council of Europe Resolution 1380 (2004)). On 30 January 2007 the European Court of Human Rights ruled by five votes to two (and on 8 July 2008, its Grand Chamber by 13 votes to four) that the 10 percent threshold imposed in Turkey does not violate the right to free elections, guaranteed by the European Convention of Human Rights. It held, however, that this same threshold could violate the Convention if imposed in a different country. It was justified in the case of Turkey in order to stabilize the volatile political situation which has obtained in that country over recent decades. The case is Yumak and Sadak v. Turkey, no. 10226/03. See also B. Bowring Negating Pluralist Democracy: The European Court of Human Rights Forgets the Rights of the Electors // KHRP Legal Review 11 (2007)

- "Results 2020 Slovak parliamentary election". Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic.

- "Results 2021 Czech legislative election". Czech Statistical Office.

- "Single Transferable Vote". Electoral Reform Society.