Parrot's sign

Parrot's sign (19th century), refers to at least two medical signs; one relating to a large skull and another to a pupil reaction.[1]

| Parrot's sign | |

|---|---|

| |

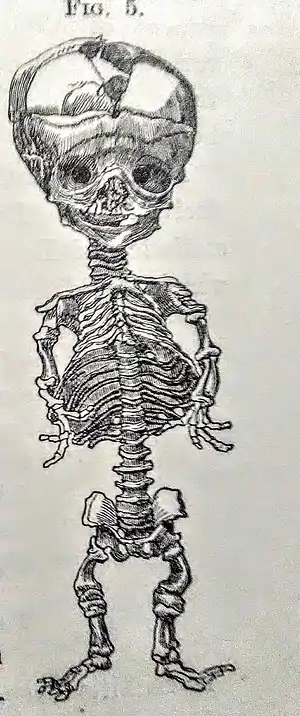

| Historic image: frontal bossing in rickets | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

One Parrot's sign describes the bony growth noted at autopsy by Joseph-Marie-Jules Parrot and Jonathan Hutchinson on the skulls of children with congenital syphilis (CS) in the 19th century. Later publications also refer to it as the frontal bossing that presents in the late type CS. Initially thought to be indicative of congenital syphilis, it was noted to be present in other conditions, particularly rickets.

Some 19th century textbooks also described the sign as the dilatation of a pupil when the back of the neck is pinched in some cases of meningitis.

Background

_CIPB1661.jpg.webp)

Marie Jules Parrot was a French physician in Paris, whose early work concentrated on the brain, followed by tuberculosis and later syphilis.[2]

Skull

Parrot's sign,[3] also known as 'Parrot's nodes'[4] and 'Parrot's bosses',[5][6] refers to the bony growth noted at autopsy by Marie Jules Parrot and Jonathan Hutchinson on the skulls of children with congenital syphilis (CS) in the 19th century.[2][7] Later publications also describe it as the frontal bossing that presents in the late type CS.[3][8] Initially thought to be indicative of congenital syphilis, it was noted to be present in other conditions, particularly rickets.[7]

A description of bone findings in CS by Parrot was published in The Lancet in 1879 following his presentation at a meeting hosted by Jonathan Hutchinson and Thomas Barlow in London.[2] In 1883 Barlow referred to the overgrowth of skull bone seen in CS as 'Parrot's swellings' and 'Parrot's bosses'.[5] The nodes were said to be indicative of CS.[9] In Timothy Holmes' and Thomas Pickering 's A Treatise on Surgery: Its Principles and Practice (1889) it was noted that Parrot's nodes could co-exist with thinning bone in the same skull.[10] The nodes were described in Gray's Anatomy (1893) as appearing like buttocks or hot cross bun depending on which skull bones were affected.[11] According to D'Arcy Power in 1895, they were first reported by Parrot and Hutchinson, and also found in rickets, and therefore could not strictly make them indicative of congenital syphilis.[7] In Hamilton and Love's A Short Practice of Surgery (1959), Parrot's nodes were said to consist of patches of periostitis in CS.[12]

Pupil

Parrot's sign was described in some ophthalmology textbooks of the 19th century as the dilatation of a pupil when the back of the neck is pinched in some cases of meningitis.[13][14]

See also

References

- Pryse-Phillips, William (2009). Companion to Clinical Neurology. Oxford University Press. p. 785. ISBN 978-0-19-536772-0.

- Cole, Garrard; Waldron, Tony; Shelmerdine, Susan; Hutchinson, Ciaran; McHugh, Kieran; Calder, Alistair; Arthurs, Owen (October 2020). "The skeletal effects of congenital syphilis: the case of Parrot's bones". Medical History. 64 (4): 467–477. doi:10.1017/mdh.2020.41. PMC 7689442. PMID 3789442.

- Harper, Kristin N.; Zuckerman, Molly K.; Harper, Megan L.; Kingston, John D.; Armelagos, George J. (2011). "The origin and antiquity of syphilis revisited: An Appraisal of Old World pre-Columbian evidence for treponemal infection". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 146 (S53): 99–133. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21613. PMID 22101689.

- Stedman, Thomas Lathrop (2005). Stedman's Medical Eponyms. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 544. ISBN 0-7817-5443-7.

- Barlow, Thomas (January 1883). "On Cases Described as "Acute Rickets" Which are Probably a Combination of Scurvy and Rickets, the Scurvy Being an Essential, and the Rickets a Variable, Element". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. MCT-66 (1): 159–219. doi:10.1177/095952878306600112. PMC 2121454. PMID 20896608.

- Thomson, Alexis; Miles, Alexander. Manual of Surgery Volume One. Libronomia Company. p. 207, 536. ISBN 978-1-4499-9483-9.

- Power, Sir D'Arcy (1895). "VII. Tumours of syphilitic disease of bone". The Surgical Diseases of Children: And Their Treatment by Modern Methods. Philadelphia: P. Blakiston. p. 155.

- Bhat M, Sriram (2019). "33. Miscellaneous". SRB's Manual of Surgery (6th ed.). Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers. p. 1174. ISBN 978-93-5270-907-6.

- Pepper, Augustus Joseph (1883). "34. Osseous lesions in congenital syphilis". Elements of Surgical Pathology. London: Cassell & Company. pp. 229–230.

- Holmes, Timothy (1889). "20. venereal diseases". In Pick, Thomas Pickering (ed.). A Treatise on Surgery: Its Principles and Practice (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Lea Brothers & Co. pp. 437–438.

- Gray, Henry (1893). Pick, T. Pickering (ed.). Anatomy, Descriptive and Surgical (13th ed.). Philadelphia: Lea Brothers & Co. p. 227.

- Bailey, Hamilton; Love, McNeill (1959). A Short Practice Of Surgery Eleventh Edition (11th ed.). London. p. 1221.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Oliver, Charles Augustus (1895). Ophthalmic Methods Employed for the Recognition of Peripheral and Central Nerve Disease. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 27.

- Norton, Arthur Brigham (1898). Ophthalmic diseases and therapeutics (PDF) (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Boericke & Tafel. p. 98.

Further reading

- Parrot, M.J. (May 1879). "The osseous lesions of hereditary syphilis" (PDF). The Lancet. 113 (2907): 696–698. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)35509-0.