Cystectomy

Cystectomy is a medical term for surgical removal of all or part of the urinary bladder. It may also be rarely used to refer to the removal of a cyst.[1] The most common condition warranting removal of the urinary bladder is bladder cancer.[2]

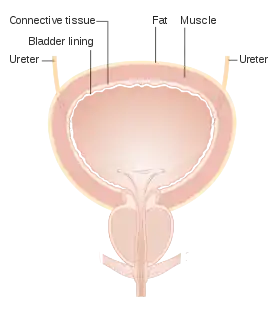

| Cystectomy | |

|---|---|

Bladder layers and anatomy | |

| ICD-9-CM | 57.6-57.7 |

| MeSH | D015653 |

| OPS-301 code | 5-576 |

Two main types of cystectomies can be performed. A partial cystectomy (also known as a segmental cystectomy) involves removal of only a portion of the bladder.[3] A radical cystectomy involves removal of the entire bladder along with surrounding lymph nodes and other nearby organs that contain cancer.[4]

Evaluation of the tissue removed during cystectomy and lymph node dissection aids in determining pathological cancer staging. This type of cancer staging can be used to determine further work-up, treatment, and follow-up needed along with potential prognosis.[5]

After the bladder has been removed, a urinary diversion is necessary to allow elimination of urine.[6]

Medical uses

Malignancy

Radical cystectomy is the recommended treatment for bladder cancer that has invaded the muscle of the bladder. Cystectomy may also be recommended for individuals with a high risk of cancer progression or failure of the cancer to respond to less invasive treatments.[6][7][8]

Types

When determining the type of cystectomy to be performed many factors are taken into consideration. Some of these factors include: age, overall health, baseline bladder function, type of cancer, location and size of the cancer, and stage of the cancer.[9]

Partial cystectomy

A partial cystectomy involves removal of only a portion of the bladder and is performed for some benign and malignant tumors localized to the bladder.[9] Individuals that may be candidates for partial cystectomy include those with single tumors located near the dome, or top, of the bladder, tumors that do not invade the muscle of the bladder, tumors located within bladder diverticulum, or cancer that is not carcinoma in situ (CIS).[7] A partial cystectomy may also be performed for removal of tumors which have originated and spread from neighboring organs such as the colon.[4]

Radical cystectomy

A radical cystectomy is most commonly performed for cancer that has invaded into the muscle of the bladder. In a radical cystectomy the bladder is removed along with surrounding lymph nodes (lymph node dissection) and other organs that contain cancer. In men, this could include the prostate and seminal vesicles. In women, this could include a portion of the vagina, uterus, Fallopian tubes, and ovaries.[4]

Technique

Open

In an open radical cystectomy a large incision is made in the middle of the abdomen from just above or next to the umbilicus to the pubic symphysis. The following information provides general steps to the procedure and may occur in varying order depending on the surgeon. The ureters are located and cut free from the bladder. The bladder is separated from surrounding structures and removed. The urethra, which drains urine from the bladder, may also be removed depending on tumor involvement. In men, the prostate may or may not be removed during this procedure. Pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND) is performed. A urinary diversion is then created and the free ends of the ureters are reconnected to the diversion.[9][10]

Minimally invasive

A minimally invasive radical cystectomy more commonly known as a robot-assisted laparoscopic radical cystectomy (RARC) may be an option for individuals depending on several factors including but not limited to: their overall health (with special attention to their lung health), body mass index (BMI), number and types of previous surgeries, along with the location and size of the bladder cancer. In a RARC several small incisions are made across the abdomen to allow placement of surgical instruments. These instruments are then connected to a surgical robot that is controlled by the surgeon. A head down (Trendelenburg) position is used and the abdomen is inflated with gas (insufflation) to allow better operating space and visualization. The remainder of the procedure is carried out in a fashion similar to the open procedure.[6][11] Compared to open surgery, minimally invasive radical cystectomy probably requires fewer blood transfusions and may shorten hospital stay slightly.[12]

For rates of major or minor complications, quality of life, time to recurrence and rates of cancerous cells left behind after surgery, there may be little to no difference between robotic and open surgery as treatment for bladder cancer in adults.[12]

Contraindications

Generally, there are no specific contraindications to having a cystectomy. However, cystectomy should not be performed in individuals who are not healthy enough to undergo a major surgical procedure. This includes individuals who cannot tolerate general anesthesia or those with severe or inadequately managed co-morbidities such as diabetes, heart, lung, kidney, or liver disease. This also includes individuals who are severely malnourished, have problems with blood clotting, or severe laboratory abnormalities. Also, individuals with an active illness or infection should delay surgery until recovery.[13][14][15]

Robotic-assisted or laparoscopic surgery is contraindicated for individuals with severe heart and lung disease. During this method of surgery the positioning and abdominal insufflation places extra strain on the chest wall impairing lung function and the ability to oxygenate the blood.[6][16]

A partial cystectomy is contraindicated in a form of bladder cancer called carcinoma in situ (CIS). Other contraindications for partial cystectomy include severely diminished bladder capacity or cancer in very close proximity to the bladder trigone, where the urethra and ureters connect to the bladder.[9]

Risks and complications

Radical cystectomy with the creation of a urinary diversion can be associated with several risks and complications due to the extent and complexity of the surgery. As with most major surgeries there is risk from anesthesia, also, risk of bleeding, blood clots, heart attack, stroke, and pneumonia or other respiratory problems. There is also a risk of infection involving the urinary tract, abdomen, and gastrointestinal tract. After the surgical incisions are closed there is a risk of infection at these sites.[17][13] Complications are similar between open and minimally invasive cystectomy techniques[18] and include the following:

Gastrointestinal tract

An ileus, where movement within the intestines slows down is the most common complication following cystectomy. This is due to a variety of factors including manipulation of the intestines due to their proximity of the bladder, the actual operation on the intestines to create a urinary diversion, or even certain medications such as narcotics. In addition to slowing of the small intestine, the small intestine can also become obstructed. After creation of a urinary diversion, intestinal contents can leak at the site where the intestine are reconnected.[19][20]

Urinary tract

With creation of a urinary diversion it is possible for the ureters to become obstructed preventing the drainage of urine from the kidneys. If this occurs, another procedure to insert a percutaneous nephrostomy tube may be need to allow drainage of urine from the body. Obstruction of the ureter most commonly occurs at the site where the ureters are reconnected to the urinary diversion created. A small, hollow, flexible tube called a stent may be placed inside the ureter at the time of surgery to possibly help the reconnection site to heal. This reconnection site is also at risk for leaking urine within the abdomen.[19][11]

If a partial cystectomy is performed, damage to the ureter may occur depending on the location of the tumor removed. This may require an additional procedure to repair.[9]

Nerve injury

Due to the location of the operation, damage to nerves in the pelvis can occur during removal of the bladder or lymph nodes. Nerves in this area are responsible for movement and sensation of the legs and include the obturator nerve, the genitofemoral nerve, and the femoral nerve.[19]

Any of these complications may require another operation or re-admission to the hospital.

Recovery

Diet before and after surgery

Immediately after surgery no food or drink is allowed due to involvement of the gastrointestinal tract in the surgery. The diet will then be slowly advanced to liquids and then solid foods as tolerated. If gastrointestinal complications such as nausea, vomiting, or abdominal bloating occur the diet may be stopped or advancement of the diet slowed down depending on the severity.[11]

For people who have difficulties eating before or after a radical cystectomy, additional nutrition may be beneficial when compared with waiting until ordinary food can be tolerated.[21] Immuno-enhancing nutrition with high levels of nutrients may decrease complications within 90 days of surgery. When compared with a multivitamin and mineral supplement, perioperative oral supplements may slightly decrease postoperative complications. It is uncertain if giving an individual undergoing a radical cystectomy amino acids, branch chain acids or preoperative oral supplements improve complications after surgery.[21] Feeding into a vein and early postoperative feeding may increase postoperative complications. These diet interventions do not appear to affect the length of hospital stay.[21]

Pain control

Intravenous pain medication such as narcotics are typically used immediately after surgery. Pain medications can be switched to an oral form once a diet is tolerated.[11]

Activity

Early activity is encouraged after surgery. Individuals may be able to walk and sit in a chair as early as the same day of surgery. Usually individuals are able to walk around their room or hospital ward within a day or two after surgery. Some individuals may require additional assistance or physical therapy in the hospital or once discharged home.[11]

Venous thromboembolism prevention

Approaches to prevent venous thromboembolism (VTE) are performed both before and after surgery. Compression devices placed around the legs or medications such as Heparin or low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) are commonly used.[11] VTE prophylaxis with LMWH may even be continued after hospital discharge if needed.[9]

Surgery follow-up

If an open cystectomy was performed, the staples closing the incision are usually removed 5 to 10 days after surgery. Further follow-up with the surgeon is typically scheduled 4 to 6 weeks after surgery and may involve laboratory or imaging studies to assess recovery along with further care and follow-up.[9]

References

- "NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms". National Cancer Institute. 2011-02-02. Retrieved 2018-01-15.

- Clark PE, Stein JP, Groshen SG, Cai J, Miranda G, Lieskovsky G, Skinner DG (July 2005). "Radical cystectomy in the elderly: comparison of clinical outcomes between younger and older patients". Cancer. 104 (1): 36–43. doi:10.1002/cncr.21126. PMID 15912515.

- "Segmental cystectomy". Retrieved 2018-01-15.

- Wieder JA (2014). Pocket Guide to Urology. US. pp. 54–57. ISBN 978-0-9672845-6-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology". www.nccn.org. 2018. Retrieved 2018-01-12.

- Hanno PM, Guzzo TJ, Malkowicz SB, Wein AJ (2014). Penn clinical manual of urology (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA. ISBN 9781455753598. OCLC 871067936.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Partin AW, Peters C, Campbell MF, Walsh PC (2016). Campbell-Walsh urology (11th ed.). Philadelphia, PA. ISBN 9781455775675. OCLC 931870910.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - McAninch JW, Lue TF, Smith DR (2013). Smith and Tanagho's general urology (18th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 9780071624978. OCLC 778040102.

- Smith Jr JA, Howards SS, Preminger GM, Dmochowski RR (2017-02-24). Hinman's atlas of urologic surgery (4th ed.). Philadelphia, PA. ISBN 9780128016480. OCLC 968341438.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Traver MA, Vaughan ED, Porter CR (December 2009). "Radical retropubic cystectomy". BJU International. 104 (11): 1800–21. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410x.2009.09043.x. PMID 20053198. S2CID 32376371.

- Bishoff JT, Kavoussi LR (December 2016). Atlas of laparoscopic and robotic urologic surgery (3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA. ISBN 9780323393263. OCLC 960041110.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rai BP, Bondad J, Vasdev N, Adshead J, Lane T, Ahmed K, et al. (Cochrane Urology Group) (April 2019). "Robotic versus open radical cystectomy for bladder cancer in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (4): CD011903. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011903.pub2. PMC 6479207. PMID 31016718.

- Garden OJ (2012). Principles and practice of surgery (6th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. ISBN 9780702043161. OCLC 797815510.

- Paterson-Brown S (2014). Core topics in general and emergency surgery (5th ed.). Edinburgh. ISBN 9780702049644. OCLC 829099224.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Lawrence PF (2013). Essentials of general surgery (5th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781784955. OCLC 768469762.

- Falcone T, Goldberg JM (2010). Basic, advanced, and robotic laparoscopic surgery. Philadelphia, PA. ISBN 9781416062646. OCLC 912279810.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Postoperative complications". Standford Health Care. 2017. Retrieved 2018-01-17.

- Lauridsen SV, Tønnesen H, Jensen BT, Neuner B, Thind P, Thomsen T (August 2017). "Complications and health-related quality of life after robot-assisted versus open radical cystectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of four RCTs". Systematic Reviews. 6 (1): 150. doi:10.1186/s13643-017-0547-y. PMC 5541663. PMID 28768530.

- Taneja SS, Shah O (2017-11-07). Taneja's complications of urologic surgery : diagnosis, prevention, and management (5th ed.). Edinburgh. ISBN 9780323392426. OCLC 1004569839.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Cookson MS (2018). Contemporary Approaches to Urinary Diversion and Reconstruction. Elsevier - Health Science. ISBN 9780323570060. OCLC 1004252333.

- Burden S, Billson HA, Lal S, Owen KA, Muneer A, et al. (Cochrane Urology Group) (May 2019). "Perioperative nutrition for the treatment of bladder cancer by radical cystectomy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (5): CD010127. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010127.pub2. PMC 6527181. PMID 31107970.