Socialist Revolutionary Party

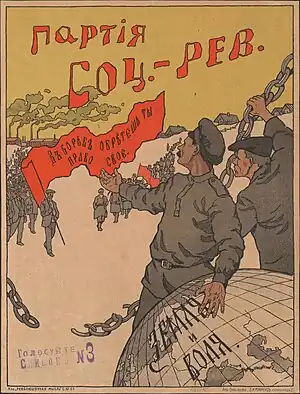

The Socialist Revolutionary Party, also Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries or Social Revolutionary Party (the SRs, СР, or Esers, эсеры, esery; Russian: Па́ртия социали́стов-революционе́ров, ПСР), was a major political party in late Imperial Russia, during both phases of the Russian Revolution, and in early Soviet Russia.

Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries Партія соціалистовъ-революціонеровъ | |

|---|---|

_emblem.svg.png.webp) | |

| Founders | Andrei Argunov Mikhail Gots Grigory Gershuni Viktor Chernov |

| Founded | 1900 |

| Dissolved | 1921 (functionally) 1940 (officially) |

| Headquarters | Moscow |

| Newspaper | Revolutsionnaya Rossiya |

| Paramilitary wing | SR Combat Organization |

| Membership (1917) | 1,000,000 |

| Ideology | Agrarian socialism[1] Democratic socialism[2] Narodism[3] Syndicalism Federalism[4] |

| Political position | Left-wing |

| International affiliation | Second International (1889–1916) Labour and Socialist International (1923–1940) |

| Colors | Red |

| Slogan | Въ борьбѣ обрѣтешь ты право свое! ("Through struggle you will attain your rights!") |

| Anthem | |

| Constituent Assembly | 324 / 767 (1917–1918) |

| 1907 Duma | 37 / 518 |

| Party flag | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

The SRs were agrarian socialists and supporters of a democratic socialist Russian republic. The ideological heirs of the Narodniks, the SRs won a mass following among the Russian peasantry by endorsing the overthrow of the Tsar and the redistribution of land to the peasants. The SRs boycotted the elections to the First Duma following the Revolution of 1905 alongside the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, but chose to run in the elections to the Second Duma and received the majority of the few seats allotted to the peasantry. Following the 1907 coup, the SRs boycotted all subsequent Dumas until the fall of the Tsar in the February Revolution of March 1917. Controversially, the party leadership endorsed the Russian Provisional Government and participated in multiple coalitions with liberal and social-democratic parties, while a radical faction within the SRs rejected the Provisional Government's authority in favor of the Congress of Soviets and began to drift towards the Bolsheviks. These divisions would ultimately result in the party splitting over the course of the summer of 1917 into the Right and Left SRs. Meanwhile, Alexander Kerensky, one of the leaders of the February Revolution and the second and last head of the Provisional Government (July–November 1917) was a nominal member of the SR party but in practice acted independently of its decisions.

By November 1917, the Provisional Government had been widely discredited by its failure to withdraw from World War I, implement land reform or convene a Constituent Assembly to draft a Constitution, leaving the soviet councils in de facto control of the country. The Bolsheviks thus moved to hand power to the 2nd Congress of Soviets in the October Revolution. After a few weeks of deliberation, the Left SRs ultimately formed a coalition government with the Bolsheviks – the Council of People's Commissioners – from November 1917 to March 1918 while the Right SRs boycotted the Soviets and denounced the Revolution as an illegal coup. The SRs obtained a majority in the subsequent elections to the Russian Constituent Assembly, with most of the party's seats going to the Right faction. Citing outdated voter-rolls which did not acknowledge the party split, and the Assembly's conflicts with the Congress of Soviets, the Bolshevik-Left SR government moved to dissolve the Constituent Assembly by force in January 1918.[5]

The Left SRs left their coalition with the Bolsheviks in March 1918 in protest against the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. An uprising against the Bolsheviks by the leadership of the Left SRs in July 1918 resulted in the immediate arrest of most of the party's members. Most of the Left SRs who opposed the uprising were gradually freed and allowed to keep their government positions, but were unable to organize a new central organ and gradually splintered into multiple pro-Bolshevik parties, which would all ultimately merge with the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) by 1921. The Right SRs supported the Whites during the Russian Civil War of 1917–1922, but the White movement's anti-socialist leadership increasingly marginalized and ultimately purged them. A small Right SR remnant, still calling itself the Socialist Revolutionary Party, continued to operate in exile from 1923 to 1940 as a member of the Labour and Socialist International.

History

Before the Russian Revolution

The party's ideology was built upon the philosophical foundation of Russia's Narodnik–populist movement of the 1860s–1870s and its worldview developed primarily by Alexander Herzen and Pyotr Lavrov. After a period of decline and marginalisation in the 1880s, the Narodnik–populist school of thought about social change in Russia was revived and substantially modified by a group of writers and activists known as neonarodniki (neo-populists), particularly Viktor Chernov. Their main innovation was a renewed dialogue with Marxism and integration of some of the key Marxist concepts into their thinking and practice. In this way, with the economic spurt and industrialisation in Russia in the 1890s, they attempted to broaden their appeal in order to attract the rapidly growing urban workforce to their traditionally peasant-oriented programme. The intention was to widen the concept of the people so that it encompassed all elements in society that opposed the Tsarist regime.

The party was established in 1902 out of the Northern Union of Socialist Revolutionaries (founded in 1896), bringing together many local socialist revolutionary groups established in the 1890s, notably the Workers' Party of Political Liberation of Russia created by Catherine Breshkovsky and Grigory Gershuni in 1899. As primary party theorist emerged Viktor Chernov, the editor of the first party organ, Revolutsionnaya Rossiya (Revolutionary Russia). Later party periodicals included Znamia Truda (Labour's Banner), Delo Naroda (People's Cause) and Volia Naroda (People's Will). Party leaders included Grigori Gershuni, Catherine Breshkovsky, Andrei Argunov, Nikolai Avksentiev, Mikhail Gots, Mark Natanson, Rakitnikov (Maksimov), Vadim Rudnev, Nikolay Rusanov, Ilya Rubanovich and Boris Savinkov.

The party's programme was democratic and socialist — it garnered much support among Russia's rural peasantry, who in particular supported their programme of land-socialization as opposed to the Bolshevik programme of land-nationalization—division of land into peasant tenants rather than collectivization into state management. The party's policy platform differed from that of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) — both Bolshevik and Menshevik — in that it was not officially Marxist (though some of its ideologues considered themselves such). The SRs agreed with Marx's analysis of capitalism, but not with his proposed solution. The SRs believed that both the labouring peasantry as well as the industrial proletariat were revolutionary classes in Russia. Whereas RSDLP defined class membership in terms of ownership of the means of production, Chernov and other SR theorists defined class membership in terms of extraction of surplus value from labour. On the first definition, small-holding subsistence farmers who do not employ wage labour are — as owners of their land — members of the petty bourgeoisie, whereas on the second definition, they can be grouped with all who provide rather than purchase labour-power, and hence with the proletariat as part of the labouring class. Chernov considered the proletariat as vanguard and the peasantry as the main body of the revolutionary army.[6]

The party played an active role in the 1905 Russian Revolution and in the Moscow and Saint Petersburg Soviets. Although the party officially boycotted the first State Duma in 1906, 34 SRs were elected while 37 were elected to the second Duma in 1907. The party also boycotted both the third Duma (1907-1912) and fourth Duma (1912–1917). In this period, party membership drastically declined and most of its leaders emigrated from Russia.

A distinctive feature of party tactics until about 1909 was its heavy reliance on assassinations of individual government officials. These tactics were inherited from SRs' predecessor in the populist movement, Narodnaya Volya (“People's Will”), a conspiratorial organisation of the 1880s. They were intended to embolden the "masses" and intimidate ("terrorise") the Tsarist government into political concessions. The SR Combat Organisation (SRCO), responsible for assassinating government officials, was initially led by Gershuni and operated separately from the party so as not to jeopardise its political actions. SRCO agents assassinated two Ministers of the Interior, Dmitry Sipyagin and Vyacheslav von Plehve, Grand Duke Sergei Aleksandrovich, the Governor of Ufa N. M. Bogdanovich and many other high-ranking officials.

In 1903, Gershuni was betrayed by his deputy, Yevno Azef, an agent of the Okhrana secret police, arrested, convicted of terrorism and sentenced to life at hard labour, managing to escape, flee overseas and go into exile. Azef became the new leader of the SRCO and continued working for both the SRCO and the Okhrana, simultaneously orchestrating terrorist acts and betraying his comrades. Boris Savinkov ran many of the actual operations, notably the assassination attempt on Admiral Fyodor Dubasov.

However, terrorism was controversial for the party from the beginning. At its 2nd Congress in Imatra in 1906, the controversy over terrorism was one of the main reasons for the split between the SR Maximalists and the Popular Socialists. The Maximalists endorsed not only attacks on political and government targets, but also economic terror (i.e. attacks on landowners, factory owners and so on) whereas the Popular Socialists rejected all terrorism. Other issues also divided the defectors from the PSR as Maximalists disagreed with the SRs' strategy of a two-stage revolution as advocated by Chernov, the first stage being popular-democratic and the second labour-socialist. To Maximalists, this seemed like the RSDLP distinction between bourgeois-democratic and proletarian-socialist stages of revolution. Maximalism stood for immediate socialist revolution. Meanwhile, the Popular Socialists disagreed with the party's proposal to socialise the land (i.e. turn it over to collective peasant ownership) and instead wanted to nationalise it (i.e. turn it over to the state). They also wanted landowners to be compensated while the PSR rejected indemnities). Many SRs held a mixture of these positions.

In late 1908, a Russian Narodnik and amateur spy hunter Vladimir Burtsev suggested that Azef might be a police spy. The party's Central Committee was outraged and set up a tribunal to try Burtsev for slander. At the trial, Azef was confronted with evidence and was caught lying, therefore he fled and left the party in disarray. The party's Central Committee, most of whose members had close ties to Azef, felt obliged to resign. Many regional organisations, already weakened by the revolution's defeat in 1907, collapsed or became inactive. Savinkov's attempt to rebuild the SRCO failed and it was suspended in 1911. Gershuni had defended Azef from exile in Zürich until his death there. The Azef scandal contributed to a profound revision of SR tactics that was already underway. As a result, it renounced assassinations ("individual terror") as a means of political protest.

With the start of World War I, the party was divided on the issue of Russia's participation in the war. Most SR activists and leaders, particularly those remaining in Russia, chose to support the Tsarist government mobilisation against Germany. Together with the like-minded members of the Menshevik Party, they became known as oborontsy ("defensists"). Many younger defensists living in exile joined the French Army as Russia's closest ally in the war. A smaller group, the internationalists, which included Chernov, favoured the pursuit of peace through cooperation with socialist parties in both military blocs. This led them to participate in the Zimmerwald and Kienthal conferences with Bolshevik emigres led by Lenin. This fact was later used against Chernov and his followers by their right-wing opponents as alleged evidence of their lack of patriotism and Bolshevik sympathies.

Russian Revolution

The February Revolution allowed the SRs to return to an active political role. Party leaders, including Chernov, returned to Russia. They played a major role in the formation and leadership of the soviets, albeit in most cases playing second fiddle to the Mensheviks. One member, Alexander Kerensky, joined the Russian Provisional Government in March 1917 as Minister of Justice, eventually becoming the head of a coalition socialist-liberal government in July 1917, although his connection with the party was tenuous. He had served in the Duma with the social democratic Trudoviks, breakaway SRs that defied the party's refusal to participate in the Duma.

After the fall of the first coalition in April–May 1917 and the reshuffling of the Provisional Government, the party played a larger role. Its key government official at the time was Chernov who joined the government as Minister of Agriculture. Chernov also tried to play a larger role, particularly in foreign affairs, but he soon found himself marginalised and his proposals of far-reaching agrarian reform blocked by more conservative members of the government. After the failed Bolshevik uprising of July 1917, Chernov found himself on the defensive as allegedly soft on the Bolsheviks and was excluded from the revamped coalition in August 1917. The party was now represented in the government by Nikolai Avksentiev, a defensist, as Minister of the Interior.

This weakening of the party's position intensified the growing divide within it between supporters of the pluralistic Constituent Assembly, and those inclined toward more resolute, unilateral action. In August 1917, Maria Spiridonova advocated scuttling the Constituent Assembly and forming an SR-only government, but she was not supported by Chernov and his followers. This spurred the formation a small breakaway faction of the SR party known as the "Left SRs". The Left SRs were willing to temporarily cooperate with the Bolsheviks. The Left SRs believed that Russia should withdraw immediately from World War I and they were frustrated that the Provisional Government wanted to postpone addressing the land question until after the convocation of the Russian Constituent Assembly instead of immediately confiscating the land from the landowners and redistributing it to the peasants.

Left SRs and Bolsheviks referred to the mainstream SR party as the "Right SR" party whereas mainstream SRs referred to the party as just "SR" and reserved the term "Right SR" for the right-wing faction of the party led by Catherine Breshkovsky and Avksentiev.[7] The primary issues motivating the split were participation in the war and the timing of land redistribution.

At the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets on 25 October, when the Bolsheviks proclaimed the deposition of the Provisional government in Petrograd, the split within the SR party became final. The Left SR stayed at the Congress and were elected to the permanent All-Russian Central Executive Committee executive (while initially refusing to join the Bolshevik government) while the mainstream SR and their Menshevik allies walked out of the Congress. In late November, the Left SRs joined the Bolshevik government, obtaining three ministries.

After the October Revolution

In the election to the Russian Constituent Assembly held two weeks after the Bolsheviks took power, the party still proved to be by far the most popular party across the country, gaining 37.6% of the popular vote as opposed to the Bolsheviks' 24%. However, the Bolsheviks disbanded the Assembly in January 1918 and after that the SR lost political significance.[8] The Left SRs became the coalition partner of the Bolsheviks in the Soviet government, although they resigned their positions after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (the peace treaty with the Central Powers that ended Russia's participation in World War I). Both wings of the SR party were ultimately suppressed by the Bolsheviks through imprisoning some of its leaders and forcing others into emigration.[9] A few Left SRs like Yakov Grigorevich Blumkin joined the Communist Party.

Dissatisfied with the large concessions granted to Imperial Germany by the Bolsheviks in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, two Chekists who were left SRs assassinated the German ambassador to Russia, Count Wilhelm Mirbach early in the afternoon on 6 July.[10] Following the assassination, the left SRs attempted a "Third Russian Revolution" against the Bolsheviks on 6–7 July, but it failed and led to the arrest, imprisonment, exile and execution of party leaders and members. In response, some SRs turned to violence. A former SR, Fanny Kaplan, tried to assassinate Lenin on 30 August. Many SRs fought for the Whites or Greens in the Russian Civil War alongside some Mensheviks and other banned socialist elements. The Tambov Rebellion against the Bolsheviks was led by an SR, Aleksandr Antonov. In Ufa the SRs' Provisional All-Russian Government was formed. However, after Admiral Kolchak was installed by the Whites as "Supreme Leader" in November 1918, he expelled all Socialists from the ranks. As a result, some SRs placed their organisation behind White lines at the service of the Red Guards and the Cheka.

Following Lenin's instructions, a trial of SRs was held in Moscow in 1922, which led to protests by Eugene V. Debs, Karl Kautsky, and Albert Einstein among others. Most of the defendants were found guilty, but they did not plead guilty like the defendants in the later show trials in the Soviet Union in the late 1920s and the 1930s.[11]

In exile

The party continued its activities in exile. A Foreign Delegation of the Central Committee was established and based in Prague. The party was a member of the Labour and Socialist International between 1923 and 1940.[12]

Electoral history

State Duma

| Year | Party leader | Performance | Government | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | Percentage | Seats | Position | |||

| 1906 | Viktor Chernov | Boycotted | 34 / 478 |

4th | Opposition | |

| 1907 (January) | Viktor Chernov | Unknown | Unknown | 37 / 518 |

5th | Opposition |

| 1907 (October) | Viktor Chernov | Boycotted | 0 / 509 |

N/A | Absent | |

| 1912 | Viktor Chernov | Boycotted | 0 / 509 |

N/A | Absent | |

| 1917 | Viktor Chernov | 17,256.911 | 37.6% | 324 / 703 |

1st | Majority |

See also

- Narodniks

- Revolutsionnaya Rossiya - organ of the Party

- Skify (almanac) - cultural almanac connected with esers

- Russian Civil War

- Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

- Ukrainian Socialist-Revolutionary Party

Notes

- Чего Хотят Социалисты Революционеры И Программа Партии Социалистов Революционеров. 1915. p. 10.

- Чего Хотят Социалисты Революционеры И Программа Партии Социалистов Революционеров. 1915. p. 8.

- Lapeshkin (1977), p. 318.

- Чего Хотят Социалисты Революционеры И Программа Партии Социалистов Революционеров. 1917.

- Tony Cliff (1978). "The Dissolution of the Constituent Assembly". Marxists.org.

- Hildermeier, M., Die Sozilrevolutionäre Partei Russlands. Cologne 1978.

- Following this pattern, Soviet authorities called the trial of the SR Central Committee in 1922 the "Trial of the Right SRs". Russian emigres and most Western historians used the term "SR" to describe the mainstream party while Soviet historians used the term "Right SR" until the fall of the USSR.

- "Constituent Assembly". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- Carr, E. H. (1950). The Bolshevik Revolution 1917–1923. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-63648-8. ISBN 978-1-349-63650-1.

- Felshtinsky, Yuri (October 26, 2010). Lenin and His Comrades: The Bolsheviks Take Over Russia 1917-1924. New York: Enigma Books. ISBN 9781929631957.

- Woitinsky, W. The Twelve Who Are to Die : the Trial of the Socialists-Revolutionists in Moscow. Berlin: 1922. p. 293.

- Kowalski, Werner. Geschichte der sozialistischen arbeiter-internationale: 1923 - 19. Berlin: Dt. Verl. d. Wissenschaften, 1985. p. 337.

Bibliography

- Lapeshkin, A. I. (1977). Yuridicheskaya literatura (ed.). The Soviet Federalism: Theory and Practice.

- Geifman, Anna (2000). Scholarly Resources Inc. (ed.). Entangled in Terror: The Azef Affair and the Russian Revolution. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-8420-2651-7.

- Hildermeier, Manfred (200). Palgrave Macmillan (ed.). The Russian Socialist Revolutionary Party Before the First World War. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312236301.

- Immonen, Hannu (1988). Finnish Historical Society (ed.). The Agrarian Program of the Russian Socialist Revolutionary Party, 1900–1911. ISBN 9518915075.

- King, Francis (2007). Socialist History Society (ed.). The Narodniks in the Russian Revolution: Russia's Socialist-Revolutionaries in 1917 – a Documentary History. ISBN 978-0-9555138-2-4.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Melancon, Michael (1990). Ohio State University Press (ed.). The Socialist Revolutionaries and the Russian Anti-War Movement, 1914–1917. Ohio State University Press. ISBN 0814205283.

- Perrie, Maureen (1976). Cambridge University Press (ed.). The Agrarian Policy of the Russian Socialist-Revolutionary Party from its Origins through the Revolution of 1905–07. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521212138.

- Radkey, Oliver (1958). Columbia University Press (ed.). The Agrarian Foes of Bolshevism: Promise and Default of the Russian Socialist Revolutionaries, February to October 1917. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231021704.

- Radkey, Oliver (1964). Columbia University Press (ed.). The Sickle Under the Hammer: The Russian Socialist Revolutionaries in the Early Months of Soviet Rule. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231025246.

- Rice, Christopher (1988). Palgrave Macmillan (ed.). Russian Workers and the Socialist Revolutionary Party Through the Revolution of 1905–07. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312016743.

- Schleifman, Nurit (1988). Palgrave Macmillan (ed.). Undercover Agents in the Russian Revolutionary Movement, SR Party 1902–1914. Macmillan. ISBN 0333432657.