Pastoral period

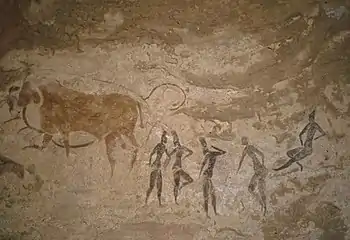

Pastoral rock art is the most common form of Central Saharan rock art, created in painted and engraved styles[1] depicting pastoralists and bow-wielding hunters in scenes of animal husbandry, along with various animals (e.g., cattle, sheep, goats, dogs),[2] spanning from 6300 BCE[3] to 700 BCE.[4] The Pastoral Period is preceded by the Round Head Period and followed by the Caballine Period.[5] The Early Pastoral Period spanned from 6300 BCE to 5400 BCE.[3] Domesticated cattle were brought to the Central Sahara (e.g., Tadrart Acacus), and given the opportunity for becoming socially distinguished, to develop food surplus, as well as to acquire and aggregate wealth, led to the adoption of a cattle pastoral economy by some Central Saharan hunter-gatherers of the Late Acacus.[6] In exchange, cultural information regarding utilization of vegetation (e.g., Cenchrus, Digitaria) in the Central Sahara (e.g., Uan Tabu, Uan Muhuggiag) was shared by Late Acacus hunter-gatherers with incoming Early Pastoral peoples.[6]

The Middle Pastoral Period (5200 cal BCE – 3800 cal BCE) is when most of the Pastoral rock art was developed.[7] In the Messak region of southwestern Libya, there were cattle remains set in areas in proximity to engraved Pastoral rock art depicting cattle (e.g., rituals of cattle sacrifice).[8] Stone monuments are also often found in proximity to these engraved Pastoral rock art.[8] A complete cattle pastoral economy (e.g., dairying) developed in the Acacus and Messak regions of southwestern Libya.[8] Semi-sedentary settlements were used seasonally by Middle Pastoral peoples depending on the weather patterns (e.g., monsoon).[8]

Amid the Late Pastoral Period, animals associated with the modern savanna decreased in appearance on Central Saharan rock art and animals suited for dry environments and animals associated with the modern Sahelian increased in appearance on Central Saharan rock art.[3] At Takarkori rockshelter, between 5000 BP and 4200 BP, Late Pastoral peoples herded goats, seasonally (e.g., winter), and began a millennia-long tradition of creating megalithic monuments, utilized as funerary sites where individuals were buried in stone-covered tumuli that were usually away from areas of dwellings in 5000 BP.[9]

The Final Pastoral Period (1500 BCE – 700 BCE) was a transitory period from nomadic pastoralism toward becoming increasingly sedentary.[4] Final Pastoral peoples were scattered, semi-migratory groups who practiced transhumance.[4] Burial mounds (e.g., conical tumuli, v-type) were created set a part from others and small-sized burial mounds were created closely together.[4] Final Pastoral peoples kept small pastoral animals (e.g., goats) and increasingly utilized plants.[4][10] At Takarkori rockshelter, Final Pastoral peoples created burial sites for several hundred individuals that contained non-local, luxury goods and drum-type architecture in 3000 BP, which made way for the development of the Garamantian civilization.[9]

Classifications

Rock art is categorized into different groups (e.g., Bubaline, Kel Essuf, Round Heads, Pastoral, Caballine, Cameline), based on a variety of factors (e.g., art method, organisms, motifs, superimposed).[5]

Compared to painted Round Head rock art, in addition to its art production method, depictions of domesticated cattle are what makes engraved/painted Pastoral rock art distinct; these distinct depictions in the Central Sahara serve as evidence for different populations entering the region.[5] The decreased appearance of large undomesticated organisms and increased appearance of one-humped camels and horses depicted in latter rock art (e.g., Pastoral, Camelline, Cabelline) throughout the Sahara serves as evidence for the Green Sahara undergoing increased desiccation.[5]

Chronology

Critique of overly simplistic and errant views presented in the long chronology is the value shown in the short chronology.[11] Yet, the rather spontaneous development of Central Saharan rock art said to occur in the later 7th millennium BP, which is presented in the short chronology, is its challenge.[11] While there is some evidence from archaeology to support this spontaneous development in 6500 BP, the amount of evidence from archaeology needed to support the short chronology, in providing explanation of the complex cultural developments (e.g., regional diversification, enduring continuity of local pastoral and pottery traditions, rock art) in the Central Sahara, is lacking.[11]

Circular logic frequently serves as a basis for the intuitively reconstructed short chronology and long chronology.[11] Nevertheless, a chronological model that can provide explication of the complex nature of the Holocene and the Sahara (e.g., cultures, peoples), at-large, is ideal.[11]

With the exception of a few instances, the common assumption is that Pastoral rock art corresponds with Pastoral Neolithic cultures, which remains largely unsubstantiated.[12] The traditional view is that of Pastoral rock art ending, followed by Horse rock art beginning and ending, and then Camel rock art beginning and ending, yet it is likely more complicated (e.g., cross-regional mixing, overlaps, long rock art traditions, some pastoralists who did not create Pastoral rock art).[12] Nevertheless, though general consensus has yet to be reached regarding correspondence between the start of the five millennia-long tradition of creating Pastoral rock art and what specific time it started in the Early Pastoral Period, the general consensus found among those who use contrasting approaches (e.g., splitter, lumper) is that the start of the Pastoral rock art tradition should be viewed as corresponding with the archaeological cultures of Early Pastoral peoples.[12]

Due to its reliance on evidence of changes caused by windblown sand, which can vary depending on the area of rock that is exposed to it, the common use of patina to discern the age of a particular rock art style, such as engravings, can be viewed as rather undependable.[13] In the case of Pastoral rock art, what may be more dependable is the likelihood that painted cattle, engraved cattle (which compose more than half of all engraved rock art), and pastoral motifs were composed by the same group of people.[13] More work needs to be done to incorporate rock art styles that portray undomesticated animals (e.g., some dating after Pastoral rock art depicting cattle and some which may date before) into the existing chronological and cultural model.[13]

More recently, black/dark patina, abundant in manganese, has been climatologically connected with the Green Sahara, connected with the engraving being performed before the development of the patina, and archaeologically connected with the Early Pastoral Period and before.[14] Gray, light-colored patina, abundant in manganese, has been climatologically connected with the drying of the Green Sahara, connected with the engraving being performed amid the development of the patina, and archaeologically connected with the Middle Pastoral Period.[14] Red patina, abundant in iron, is climatologically connected with a dry Sahara, connected with the engraving being performed after the development of the patina and before/amid mineral buildup, and archaeologically connected with the Late Pastoral Period and Final Pastoral Period.[14] The absence of patina has been climatologically connected with a fully dry Sahara, too new for mineral buildup, and archaeologically connected with the Garamantian period and after.[14]

A terminus post quem for the engraved rock art is established via evidence from archaeology for domesticated animals in the Central Sahara.[14] Archaeological evidence for domesticated cattle is limited for the Early Pastoral Period (dated to the early 6th millennium BCE), increases to established cattle pastoral economy for the Middle Pastoral Period (dated to the 5th millennium BCE), and decreases by the Garamantian period (e.g., classical period, late period).[14]

Patina containing an abundant amount of manganese underlie 53% of engraved animal rock art has been found at Wadi al-Ajal, which determines it to be probable that the engraved animal rock art (e.g., elephant, hartebeest, reedbuck, rhino) at Wadi al-Ajal were engraved amid, or even prior to, the Early Pastoral Period and the Middle Pastoral Period.[15] At Wadi al-Ajal, there were ten scattered archaeological sites - nine sites from the Early Pastoral Period and Middle Pastoral Period as well as one site likely from the Pre-Pastoral Period.[15] Numerous engraved Pastoral rock art of animals may reflect an increase in activity (e.g., increased utilization of natural resources) among pastoralists amid the Early Pastoral Period and Middle Pastoral Period.[15]

Amid the Middle Pastoral Period, dairy farming and cattle grazing at pastures in the area of Wadi al-Ajal as well as transhumance between the southern region of the Messak and Wadi al-Ajal may have occurred.[15]

Amid the Late Pastoral Period and Final Pastoral Period (3800 BCE – 1000 BCE), out of all of the engraved animal rock art, which included desert-adaptable animals (e.g., Barbary sheep, Ostriches), red-colored patina developed and underlay 33% of the engraved animal rock art at Wadi al-Ajal.[15] Desertification availed new areas to creating Pastoral rock art that were previously unavailable in prior times.[15]

Climate

Early Pastoral Period

From 8000 BP to 7500 BP, the climate of the Central Sahara may have been arid.[6] From 6900 BP to 6400 BP, the climate of the highlands and lowlands of the Central Sahara may have been humid; consequently, from 6600 BP to 6500 BP, the lakes in Edeyen of Murzug and Uan Kasa growing to their largest.[6]

Middle Pastoral Period

The state of the Central Saharan environment amid the Early Pastoral Period and Middle Pastoral Period were favorable.[16] Between the two periods, there was an arid period, which lasted from 7300 cal BP to 6900 cal BP.[16]

Late Pastoral Period

A considerably arid environment may have been present, which also involved wind-caused erosion in rockshelters.[6] After 5000 BP, physical breakdown of rockshelters may have occurred as intense aridity began to set in throughout the region of the Sahara and a plant landscape (e.g., grasslands with Chenopodiaceae, Compositae, psammophilous plants) similar to a steppe and desert region may have developed.[6]

Final Pastoral Period

The environment became increasingly dry and oases began to develop.[4]

Origins of Pastoralists

Pastoral Rock Art

Di Lernia et al. theorized: In 10,000 BP, black African hunter-gatherers may have migrated northward, along with the tropical monsoon rain system, from Sub-Saharan western Africa into the Central Sahara, particularly the Acacus region of Uan Muhuggiag; thereafter, in 7000 BP, pastoralists from the Near East (e.g., Palestine, Mesopotamia) and Eastern Sahara are believed to have migrated into the Central Sahara, along with their pastoral animals (e.g., cattle, goats).[17] Based on the view that some rock art from the Acacus region of Libya portrayed persons with the phenotype (e.g., style and profile of the face) of white people, Savino Di Lernia characterized the Central Saharan pastoral culture that produced the child mummy of Uan Muhuggiag as mixed race.[17]

Pastoral rock art is thought to portray Mediterranean and Sub-Saharan African peoples.[2] Most rock art is thought to predominantly depict Mediterranean peoples and depict fewer Sub-Saharan African peoples by 4000 BP.[2] However, other scholars have contested this as Joseph Ki-Zerbo argues this view reflected modern, racial theories which "give prominence to influences from outside Africa [which] are based on flimsy foundations" and rather all African physical types are reflected in the rock iconography.[18][19]

Round Head rock art portrays human artforms with additional attributes (e.g., occasionally wielding bows, body designs, masks) and undomesticated animals (e.g., Barbary sheep, antelope, elephants, giraffes); the final period of the Round Head rock art portrayals have been characterized as Negroid (e.g., dominant mandible, big lips, rounded nose).[20] Pastoral rock art, as distinct (e.g., technique, themes) from Round Head rock art, portrays situations from pastoral life and domesticated cattle; its portrayals have been characterized as Europoid (e.g., thin lips, pointed nose).[20]

Some rock art from the Pastoral period seem to portray Africans with Caucasian phenotypes residing among other African ethnic groups and also seem to portray some women with yellow-colored hair.[21] While this may be the case, the uncertainty of whether or not the rock art portrayals actually reflect the phenotypic differences found among the African ethnic groups that occupied the region of ancient Libya has resulted in caution about the opinions formed regarding these rock art portrayals.[21]

Pastoralists

The earliest pastoralists, who brought domesticated sheep, goat, and cattle along with them to the Central Sahara, amid the Pastoral Period (8000 BP – 7000 BP), have been characterized as Proto-Berbers.[22]

At Gobero, in Niger, hunter-gatherers dwelled amid the early period of the Holocene and ceased doing so by 8500 BP; after one thousand years of vacancy, pastoralists began dwelling by 7500 BP; these phenotypically (e.g., tall and robust compared smaller and tiny) and culturally (e.g., hunter-gatherer compared to pastoralist) distinct peoples are viewed as being similar to what occurred in the Acacus region of Libya and Tassili region of Algeria.[20]

After having dwelled among one another in the Central Sahara, by 4000 BP, some of the hunter-gatherers, who created the Round Head rock art, may have associated with, admixed with, and adapted the culture of incoming cattle pastoralists.[20]

In the Acacus region, at the Uan Muhuggiag rockshelter, there was a child mummy (5405 ± 180 BP) and an adult (7823 ± 95 BP/7550 ± 120 BP).[23] In the Tassili n'Ajjer region, at Tin Hanakaten rockshelter, there was a child (7900 ± 120 BP/8771 ± 168 cal BP), with cranial deformations due to disease or artificial cranial deformation that bears a resemblance with ones performed among Neolithic-era Nigerians, as well as another child and three adults (9420 ± 200 BP/10,726 ± 300 cal BP).[23] Based on examination of the Uan Muhuggiag child mummy and Tin Hanakaten child, the results verified that these Central Saharan peoples from the Epipaleolithic, Mesolithic, and Pastoral periods possessed dark skin complexions.[23] Soukopova (2013) thus concludes: “The osteological study showed that the skeletons could be divided into two types, the first Melano-African type with some Mediterranean affinities, the other a robust Negroid type. Black people of different appearance were therefore living in the Tassili and most probably in the whole Central Sahara as early as the 10th millennium BP.”[23]

Neolithic agriculturalists, who may have resided in Northeast Africa and the Near East, may have been the source population for lactase persistence variants, including –13910*T, and may have been subsequently supplanted by later migrations of peoples.[24] The Sub-Saharan West African Fulani, the North African Tuareg, and European agriculturalists, who are descendants of these Neolithic agriculturalists, share the lactase persistence variant –13910*T.[24] While shared by Fulani and Tuareg herders, compared to the Tuareg variant, the Fulani variant of –13910*T has undergone a longer period of haplotype differentiation.[24] The Fulani lactase persistence variant –13910*T may have spread, along with cattle pastoralism, between 9686 BP and 7534 BP, possibly around 8500 BP; corroborating this timeframe for the Fulani, by at least 7500 BP, there is evidence of herders engaging in the act of milking in the Central Sahara.[24]

Origins of Pastoral Animals and Locations of Domestication

Near Eastern Introduction of Domesticated Cattle Into Africa

Rather than the domesticating of cattle happening in the region of the Tadrart Acacus, it is considered more likely that domesticated cattle were introduced to the region.[6] Cattle are thought to not have entered Africa independently, but rather, are thought to have been brought into Africa by cattle pastoralists.[25] By the end of the 8th millennium BP, domesticated cattle are thought to have been brought into the Central Sahara.[11] The Central Sahara (e.g., Tin Hanakaten, Tin Torha, Uan Muhuggiag, Uan Tabu) was a major intermediary area for the distribution of domesticated animals from the Eastern Sahara to the Western Sahara.[26]

Based on cattle remains near the Nile dated to 9000 BP and cattle remains near Nabta Playa and Bir Kiseiba reliably dated to 7750 BP, domesticated cattle may have appeared earlier, near the Nile, and then expanded to the western region of the Sahara.[20] Though undomesticated aurochs are shown, via archaeological evidence and rock art, to have dwelled in Northeast Africa, aurochs are thought to have been independently domesticated in India and the Near East.[24] After aurochs were domesticated in the Near East, cattle pastoralists may have migrated, along with domesticated aurochs, through the Nile Valley and, by 8000 BP, through Wadi Howar, into the Central Sahara.[24]

The mitochondrial divergence of undomesticated Indian cattle, European cattle, and African cattle (Bos primigenius) from one another in 25,000 BP is viewed as evidence supporting the conclusion that cattle may have been domesticated in Northeast Africa,[27] particularly, the eastern region of the Sahara,[27][28] between 10,000 BP and 8000 BP.[29] Cattle (Bos) remains may date as early as 9000 BP in Bir Kiseiba and Nabta Playa.[29] While the mitochondrial divergence between Eurasian and African cattle in 25,000 BP can be viewed as supportive evidence for cattle being independently domesticated in Africa, introgression from undomesticated African cattle in Eurasian cattle may provide an alternative interpretation of this evidence.[26]

Independent Domestication of African Cattle In Africa

The time and location for when and where cattle were domesticated in Africa remains to be resolved.[20]

Osypińska (2021) indicates that an "archaeozoological discovery made at Affad turned out to be of great importance for the entire history of cattle on the African continent. A large skull fragment and a nearly complete horn core of an auroch, a wild ancestor of domestic cattle, were discovered at sites dating back 50,000 years and associated with the MSA. These are the oldest remains of the auroch in Sudan, and they also mark the southernmost range of this species in the world.[30] Based on the cattle (Bos) remains found at Affad and Letti, Osypiński (2022) indicates that it is "justified to raise again the issue of the origin of cattle in Northeast Africa. The idea of domestic cattle in Africa coming from the Fertile Crescent exclusively is now seen as having serious shortcomings."[31]

Indian humped cattle (Bos indicus) and North African/Middle Eastern taurine cattle (Bos taurus) are commonly assumed to have admixed with one another, resulting in Sanga cattle as their offspring.[32] Rather than accept the common assumption, admixture with taurine and humped cattle is viewed as having likely occurred within the last few hundred years, and Sanga cattle are viewed as having originated from among African cattle within Africa.[32] Regarding possible origin scenarios for Sub-Saharan African Sanga cattle, domesticated taurine cattle were introduced into North Africa, admixed with domesticated African cattle (Bos primigenius opisthonomous), resulting in offspring (the oldest being the Egyptian/Sudanese longhorn, some to all of which are viewed as Sanga cattle), or more likely, domesticated African cattle originated in Africa (including Egyptian longhorn), and became regionally diversified (e.g., taurine cattle in North Africa, zebu cattle in East Africa).[32]

The managing of Barbary sheep may be viewed as parallel evidence for the domestication of amid the early period of the Holocene.[33] Near Nabta Playa, in the Western Desert, between 11th millennium cal BP and 10th millennium cal BP, semi-sedentary African hunter-gatherers may have independently domesticated African cattle as a form of reliable food source and as a short-term adaptation to the dry period of the Green Sahara, which resulted in a limited availability of edible flora.[33] African Bos primigenius fossils, which have been dated between 11th millennium cal BP and 10th millennium cal BP, have been found at Bir Kiseiba and Nabta Playa.[33]

In the Western Desert, at the E-75-6 archaeological site, amid 10th millennium cal BP and 9th millennium cal BP, African pastoralists may have managed North African cattle (Bos primigenius) and continually used the watering basin and well and as water source.[33] In the northern region of Sudan, at El Barga, cattle fossils found in a human burial serve as supportive evidence for cattle being in the area.[33]

While this does not negate that it is possible for cattle from the Near East to have migrated into Africa, a greater number of African cattle in the same area share the T1 mitochondrial haplogroup and atypical haplotypes than in other areas, which provides support for Africans independently domesticating African cattle.[33] Based on a small sample size (SNPs from sequences of whole genomes), African cattle split early from European cattle (Taurine).[33] African cattle, bearing the Y2 haplogroup, form a sub-group within the overall group of taurine cattle.[33] As a Near Eastern origin of African cattle requires a conceptual bottleneck to sustain the view, the diverseness of the Y2 haplogroup and T1 haplogroup do not support the view of a bottleneck having occurred, and thus, does not support a Near Eastern origin for African cattle.[33] Altogether, these forms of genetic evidence provide the strongest support for Africans independently domesticating African cattle.[33]

Goat

From the Near East, between 6500 BP and 5000 BP, sheep and goats expanded into the Central Sahara.[34]

Sheep

The most early domesticated sheep remnants in Africa (7500 BP – 7000 BP) were found in the eastern Sahara, Nile Delta, and Red Sea Hills (specifically, 7100 BP – 7000 BP).[35] Domesticated sheep, which are thought to have probable origins in the Sinai Peninsula (7000 BP), may have, due to climate instability and water shortages, migrated from the Levant to Libya (6500 BP – 6800 BP), then to the central Nile River Valley (6000 BP), then to the Central Sahara (6000 BP), and finally, into West Africa (3700 BP).[35]

Pastoral Rock Art and Pastoralists

Among thousands of archaeological sites, which usually have several different periods of rock art traditions (e.g., Wild Fauna, Round Head, Pastoral, Horse, Camel) present at a single site and almost 80% of sites that are found in rockshelters, the most common form of Saharan rock art is the engraved and painted Pastoral rock art.[1] Central Saharan cattle herders, such as those of the Acacus region, had a sense of monumentality.[36] Pastoral rock art, which are of latter times, are frequently found covering the Round Head rock art of earlier times.[11] Between 7000 BP and 4000 BP, the Pastoral rock art tradition may have persisted, and, based on excavated evidence and samples of paint from the Tadrart Acacus region, may have reached its pinnacle during the 6th millennium BP.[1] Round Head rock art is distinct from engraved and painted Pastoral rock art.[2] While Pastoral rock art is largely characterized by pastoralists and bow-wielding hunters in scenes of animal husbandry, with various animals (e.g., cattle, sheep, goats, dogs), Round Head rock art may be characterized as being rather celestial.[2] Various kinds of monumental stone structures (e.g., alignments, arms, crescents, heap of stones, keyholes, platforms, rings, standings stones, stone cairns/tumuli) have existed in the Central Sahara, spanning from the Middle Pastoral Period among cattle pastoralists to the Garamantes.[10] Cattle sculptures, which may have served as religious symbols, were also created during the Pastoral Period.[37]

In the late period of the Pleistocene as well as the early and middle periods of the Holocene in West Africa and North Africa, peoples with Sudanese, Mechtoid, and Proto-Mediterranean/Proto-Berber skeletal types (which are outdated, problematic physical anthropological concepts) occupied these regions, and thus, occupied the Central Sahara (e.g., Fozziagiaren I, Imenennaden, Takarkori, Uan Muhuggiag) and Eastern Sahara (e.g., Nabta Playa).[38] There are various types of stone constructions (e.g., Keyhole: 4300 BCE – 3200 BCE; Platform: 3800 BCE – 1200 BCE; Cone-Shaped: 3750 BCE; Crescent – 3300 BCE – 1900 BCE; Aligned Structures: 1900 BCE – Beginning of Islamic Period; Crater Tumulus: 1900 BCE – Beginning of Islamic Period) in Niger.[38] At Adrar Bous, in Niger, the most common type (71.66%) of tumuli are platform tumuli; the second most common (16.66%) type of tumuli are cone-shaped tumuli.[38] The earlier “black-face rock art style” of Tassili rock art has been viewed as sharing cultural affinity with the Fulani people.[38] Proto-Berbers, who have been viewed as having migrated into the Central Sahara from Northeast Africa, have been associated with the latter “white-face rock art style” (e.g., pale-skinned figures, beads, long dresses, cattle, cattle-related activities) that emerged in Tassili N’Ajjer in 3500 BCE.[38] In 3800 BCE, the most early of platform tumuli developed in the Central Sahara, which has been viewed as a cultural practice that was brought into the Central Sahara by Proto-Berbers.[38] The inconsistencies within the view that Proto-Berbers migrated from Northeast Africa and brought the platform tumuli tradition into the Central Sahara is that the measurements for the skeletal types of the Central Sahara do not begin to match the skeletal types of Northeast Africa until after 2500 BCE and the constructing of platform tumuli at Adrar Bous, in Niger, began in 3500 BCE.[38] In the Western Sahara, the pastoralist-associated hearths, pottery from the Late Neolithic, and the most common type of Western Saharan tumuli – cone-shaped tumuli (which emerged earliest in Niger by 3750 BCE and has connections with the Mediterranean), are probably associated with Protohistoric Berbers[38] At Gobero, in Niger, the period that has been characterized as pastoral is based on only two cattle remnants and an absence of sheep/goat remnants; until the end of the mid-Holocene, there is limited evidence for nomadic lifeways; there is also anatomical evidence that is indicative of general population continuity amid the mid-Holocene at Gobero.[38] The tumuli tradition of the Central Sahara likely developed as a result of interactions between culturally and ethnically different Central Saharan peoples (e.g., as depicted in Central Saharan rock art), within the context of changing and varied Central Saharan ecology.[38] The traits (e.g., hierarchy, social complexity) of the earlier Central Saharan pastoral culture contributed to the latter development of state formation in West Africa, Nubia, and the Sahara.[38]

In 10,000 BP, the tropical monsoon rain system from Sub-Saharan western Africa changed direction and moved northward into the Central Sahara.[17] As the monsoon rain system moved northward into the Central Sahara, amid a period which brought along with the development of a savanna environment (akin to the savanna environments of contemporary Kenya, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe), egalitarian black African hunter-gatherers also migrated northward into the Central Sahara (e.g., Uan Muhuggiag rock shelter, Acacus Mountains, Libya).[17] Later, in 7000 BP, pastoralists migrated into the Central Sahara, along with their pastoral animals (e.g., cattle, goats).[17] The pastoralists may have migrated from the Near East (e.g., Mesopotamia, Palestine) and from the Eastern Sahara.[17] Saharan pastoral culture spanned throughout northern Africa (e.g., Algeria, Chad, Egypt, Libya, Mali, Niger, Sudan), including in Niger where human burials, pottery, and rock art were found.[17] At Uan Muhuggiag, the pastoral culture, which has been characterized as mixed race, may have begun earlier than 5500 BP.[17] In the region, there were various kinds of flora (e.g., Typha) and fauna (e.g., hippopotamuses, crocodiles, elephants, lions, giraffe, gazelle).[17] At the Uan Muhuggiag rock shelter, around 5600 BP, a two and a half year old Sub-Saharan African boy (determined through examination of the complete set of human remains, which included a Negroid skull and remnants of dark skin) was mummified (e.g., embalmed, eviscerated – removal of organs from the abdomen, chest, and thorax, followed by replacement with organic preservatives to prevent decomposition, and wrapped in the skin of an antelope and leaves for insulation) utilizing advanced mummification methods.[17] As the child mummy of Uan Muhuggiag was buried with a necklace made from ostrich eggshells, this may indicate that it was a compassionate, ceremonial burial relating to the afterlife.[17] As the earliest dated mummy in Africa, the child mummy of Uan Muhuggiag may date at least one thousand years older than the mummies of ancient Egypt, and may belong to a Central Saharan mummification tradition that may date hundreds to thousands of years prior to the mummification of the child mummy of Uan Muhuggiag.[17] At Mesak Settafet (e.g., Wadi Mathendous), there was engraved rock art depicting cattle and human forms with animal heads (e.g., jackal/dog masks) as well as a presence of cattle culture, and particularly, near a circularly arranged set of stone monuments, evidence of cattle being sacrificed and pottery given as ritual offering.[17] In the Nile Valley region of Sudan, decorated Saharan pottery, which was dated to 6000 BP and stands in contrast to local pottery that were not decorated, was also found.[17] As Central Saharan cattle pastoral culture emerged thousands of years earlier than when it reached its apex in the Nile Valley, Central Saharan pastoral culture produced the cultural motif of a human form wearing a jackal mask may date one thousand years earlier than 5600 BP (date based on tested organic material from rock shelter wall crevice) and appears one thousand years earlier than in the Nile Valley, and Central Saharan pottery was found in the Nile Valley, Central Saharan pastoral culture may have contributed to the latter development of ancient Egypt (e.g., decoration of pottery; cattle pastoralism; funerary culture and the mythological guardian of the dead and god of embalming, Anubis).[17] Though the descendants of the people of Uan Muhuggiag may have vacated the region five hundred years after the embalming of the child of Uan Muhuggiag due to increasing aridification, and the occurrence of demic diffusion is possible, it is more likely that knowledge from the Central Saharan pastoral culture may have been transmitted into the Nile Valley through cultural diffusion in 6000 BP.[17]

Pastoralism, possibly along with social stratification, and Pastoral rock art, emerged in the Central Sahara between 5200 BCE and 4800 BCE.[39] Funerary monuments and sites, within possible territories that had chiefdoms, developed in the Saharan region of Niger between 4700 BCE and 4200 BCE.[39] Cattle funerary sites developed in Nabta Playa (6450 BP/5400 cal BCE), Adrar Bous (6350 BP), in Chin Tafidet, and in Tuduf (2400 cal BCE – 2000 cal BCE).[39] Thus, by this time, cattle religion (e.g., myths, rituals) and cultural distinctions between genders (e.g., men associated with bulls, violence, hunting, and dogs as well as burials at monumental funerary sites; women associated with cows, birth, nursing, and possibly the afterlife) had developed.[39] Preceded by assumed earlier sites in the Eastern Sahara, tumuli with megalithic monuments developed as early as 4700 BCE in the Saharan region of Niger.[39] These megalithic monuments in the Saharan region of Niger and the Eastern Sahara may have served as antecedents for the mastabas and pyramids of ancient Egypt.[39] During Predynastic Egypt, tumuli were present at various locations (e.g., Naqada, Helwan).[39] Between 7500 BP and 7400 BP, amid the Late Pastoral Neolithic, religious ceremony and ceremonial burials, with megaliths, may have served as a cultural precedent for the latter religious reverence of the goddess Hathor during the dynastic period of ancient Egypt.[27]

By at least 4th millennium BCE, as indicated via the painted rock art of Tassili n’Ajjer, Proto-Fulani culture may have been present in area of Tassili n’Ajjer.[40] The Agades cross, a fertility amulet worn by Fulani women, may be associated with the hexagon-shaped carnelian piece of jewelry depicted in the rock art at Tin Felki.[40] At Tin Tazarift, the depiction of a finger may allude to the hand of the mythic figure, Kikala, the first Fulani pastoralist.[40][41] At Uan Derbuaen rockshelter of eastern Tassili, composition six may depict a white ox, under the spell of serpent-related animals, crossing through a U-shaped gate of vegetation, toward a powerful benevolent figure, in order to undo the spell on the ox.[42] Composition six has been interpreted as portraying the Lotori ceremonial rite of Sub-Saharan West African Fulani herders.[42] The annual Lotori ceremonial rite, held by Fulani herders, occurs at a selected location and period of time,[43] and commemorates the ox and its origination in a source of water.[40][41] The Lotori ceremonial rite promotes good health (e.g., prevent epizooties, prevent illness, prevent sterility)[43][42] and reproductive success of cattle by having the cattle cross through a gate of vegetation, and thus, the continuity of the pastoral wealth of the nomadic pastoralist Fulani.[43] The interpretation of composition six as portraying the Lotori ceremonial rite, along with other forms of evidence, have been used to support the conclusion that modern Sub-Saharan West African Fulani herders are descended from peoples of the Sahara.[42] With increasing aridification during the Pastoral Period, Pastoral rock artists (e.g., Fulani) of the Central Sahara migrated into regions of Sub-Saharan Africa, such as Mali.[37]

After migrating from the Central Sahara, by 4000 BP, the Mande peoples of West Africa established their agropastoral civilization of Tichitt[44] in the Western Sahara.[45] The painted Pastoral rock art of Tassili n'Ajjer, Algeria and engraved Pastoral rock art of Niger bear resemblance (e.g., color markings of the cattle) with the engraved cattle portrayed in the Dhar Tichitt rock art in Akreijit.[46] The engraved cattle pastoral rock art of Dhar Tichitt, which are displayed in enclosed areas that may have been used to pen cattle, is supportive evidence for cattle bearing ritualistic significance for the peoples of Dhar Tichitt.[46]

Early Pastoral Period

In the Tadrart Acacus, the period of the Late Acacus hunter-gatherers was followed by an arid period in 8200 BP, which made way for the period of incoming Early Pastoral peoples.[47] The Early Pastoral Period spanned from 6300 BCE to 5400 BCE,[3] or from 7400 BP to 5200 BP.[10] Domesticated cattle were brought to the Central Sahara (e.g., Tadrart Acacus), and given the opportunity for becoming socially distinguished, to develop food surplus, as well as to acquire and aggregate wealth, led to the adoption of a cattle pastoral economy by some Central Saharan hunter-gatherers of the Late Acacus.[6] In exchange, cultural information regarding utilization of vegetation (e.g., Cenchrus, Digitaria) in the Central Sahara (e.g., Uan Tabu, Uan Muhuggiag) was shared by Late Acacus hunter-gatherers with incoming Early Pastoral peoples.[6] In the Tadrart Acacus, settlements were most abundant in enclosed spaces.[6] Early Pastoral peoples may have dwelled in open plains areas to gather as well as access water sources (e.g., lakes) and dwelled in mountains with rockshelters during arid seasons.[6] Areas occupied by Early Pastoral peoples left behind sandstone-based ceramics (e.g., potsherds), distinct from the ceramics of the Late Acacus (e.g., sandstone-based material compared to granite-based material with an alternately pivoting stamp design), and bone implements that may have come from domesticated cattle remains.[6] Early Pastoral rock art are sometimes found above earlier composed Round Head rock art.[6] While stone implements may have also been utilized by Early Pastoral peoples, they did not differ from earlier Central Saharan hunter-gatherers of the Early Acacus.[6] In the collective memory of Early Pastoral peoples, rockshelters (e.g., Fozzigiaren, Imenennaden, Takarkori) in the Tadrart Acacus region may have served as monumental areas for women and children, as these were where their burial sites were primarily found.[10] Engraved rock art has been found on various kinds of stone structures (e.g., stone arrangements, standing stones, corbeilles – ceremonial monuments) in the Messak Plateau.[10]

At Takarkori rockshelter, Early Pastoral peoples utilized fireplaces between 7400 BP and 6400 BP.[9] Early Pastoral peoples established a centuries-long burial tradition of utilizing rockshelters as special locations for burial of the dead (e.g., women, children), which, by the time of the Middle Pastoral peoples, ceased to be practiced.[9] Early Pastoral peoples buried more of their dead in comparison to late Middle Pastoral peoples at least partly due to seasonal dwelling and possibly discovering earlier burials made by Early Pastoral peoples.[9] Early Pastoral peoples buried their dead via stone-covered tumuli, where the entombed dead were covered in stones.[9]

Middle Pastoral Period

Amid and shortly after aridification in the Acacus region, between 7300 cal BP and 6900 cal BP, Middle Pastoral peoples and Early Pastoral peoples interacted with one another, resulting in the merging of Middle Pastoral peoples and Early Pastoral peoples and replacing of Early Pastoral peoples with Middle Pastoral peoples.[16]

The Middle Pastoral Period (5200 cal BCE – 3800 cal BCE) is when most of the Pastoral rock art was developed.[7] In the Messak region of southwestern Libya, there were cattle remains set in areas in proximity to engraved Pastoral rock art depicting cattle (e.g., rituals of cattle sacrifice).[8] Stone monuments are also often found in proximity to these engraved Pastoral rock art.[8] A complete cattle pastoral economy (e.g., dairying) developed in the Acacus and Messak regions of southwestern Libya.[8] Semi-sedentary settlements were used seasonally by Middle Pastoral peoples depending on the weather patterns (e.g., monsoon).[8] Wadi Bedis meander had 42 stone monuments (e.g., mostly corbeilles, stone structures and platforms, tumuli). Ceramics (e.g., potsherds) and stone implements were found along with 9 monuments bearing engraved rock art.[8] From 5200 BCE to 3800 BCE, burial of animals occurred.[8] Nine decorated ceramics (e.g., mostly rocker stamp/plain edge design, sometimes alternately pivoting stamp design) and sixteen stone maces were found.[8] Some stone maces, used literally or symbolically to slaughter the cattle (e.g., Bos taurus), were ceremonially set near the head of sacrificed cattle or stone monuments.[8] These ceremonies were shown across several centuries worth of excavated sites.[8] Goats or hoofed animals were found as well.[8] While the possible reason (e.g., appeal for rain, convey cultural identity, death, drying of the Sahara, initiation, marriage, transhumance) for the occurrence of cattle sacrificial ceremonies may not be able to verified, it may be the case that they occurred during events when distinct pastoral groups assembled together.[8] Altogether, this has been characterized as being an African Cattle Complex.[8]

At the Uan Muhuggiag rockshelter, the child mummy of Uan Muhuggiag has been radiocarbon dated, via the deepest coal layer where it was found, to 7438 ± 220 BP, and, via the animal hide it was wrapped in, to 5405 ± 180 BP,[48] which has been calibrated to 6250 cal BP.[16] Another date for the animal hide made from the skin of an antelope, which was accompanied by remnants of a grind stone and a necklace made from the eggshell of an ostrich, is 4225 ± 190 BCE.[38]

At Takarkori rockshelter, Middle Pastoral peoples developed a completely cattle (Bos taurus) pastoralist-driven economic system (e.g., pottery, milking) between 6100 BP and 5100 BP.[9] Middle Pastoral peoples, who occupied rockshelters seasonally, buried their dead in pits at varied depths.[9] Thirteen human remains as well as two female human remains that had undergone incomplete, natural mummification were found at Takarkori rockshelter, which were dated to the Middle Pastoral Period (6100 BP – 5000 BP).[49] More specifically, with regard to the mummies, one of the naturally mummified females was dated to 6090 ± 60 BP and the other was dated to 5600 ± 70 BP.[49][50][51] These two naturally mummified females were the earliest dated mummies to undergo histological inspection.[49] The two naturally mummified women carried basal haplogroup N.[52]

In 5000 BP, the development of megalithic monuments (e.g., architecture) increased in the Central Sahara.[10] In the Central Sahara, the tumuli tradition originated in the Middle Pastoral Period and transformed amid the Late Pastoral Period (4500 BP – 2500 BP).[53]

Late Pastoral Period

Amid the Late Pastoral Period, animals associated with the modern savanna decreased in appearance on Central Saharan rock art and animals suited for dry environments and animals associated with the modern Sahelian increased in appearance on Central Saharan rock art.[3] Rockshelters in mountainous areas may have become utilized infrequently and bodies of water (e.g., lakes) in plains areas began to become sebkhas, resulting in settlements in those areas being temporary.[6] Consequently, development of increasingly nomadic forms of pastoralism began to occur and broad distribution of Late Pastoral settlements (e.g., Edeyen of Murzuq, Erg Van Kasa, Mesak Settafet, Tadrart Acacus, Wadi Tanezzuft).[6] Some stones and ceramics, as well as evidence of ovicaprid pastoralism, have been found at Late Pastoral Period sites.[6] At Takarkori rockshelter, between 5000 BP and 4200 BP, Late Pastoral peoples herded goats, seasonally (e.g., winter), and began a millennia-long tradition of creating megalithic monuments, utilized as funerary sites where individuals were buried in stone-covered tumuli that were usually away from areas of dwellings in 5000 BP.[9]

Final Pastoral Period

The Final Pastoral Period (1500 BCE – 700 BCE) was a transitory period from nomadic pastoralism toward becoming increasingly sedentary.[4] Final Pastoral peoples were scattered, semi-migratory groups who practiced transhumance.[4] Burial mounds (e.g., conical tumuli, v-type) were created set a part from others and small-sized burial mounds were created closely together.[4] Final Pastoral peoples kept small pastoral animals (e.g., goats) and increasingly utilized plants.[4][10] At Takarkori rockshelter, Final Pastoral peoples created burial sites for several hundred individuals that contained non-local, luxury goods and drum-type architecture in 3000 BP, which made way for the development of the Garamantian civilization.[9] Final Pastoral peoples were in contact the Garamantes.[54] Later, Garamantes acquired a monopoly on the oasis-based economy of the southern region of Libya.[54]

References

- Gallinaro, Marina; Di Lernia, Savino (November 2011). "Working in a UNESCO WH site. problems and practices on the rock art of tadrart akakus (SW Libya, central Sahara)". Journal of African Archaeology. 9 (2): 162, 167, 169, 173. doi:10.3213/2191-5784-10198. ISSN 1612-1651. OCLC 7787754660. S2CID 162084812.

- Coulson, David; Campbell, Alec (2010). "Rock Art of the Tassili n Ajjer, Algeria" (PDF). Adoranten: 30, 33, 35.

- Guagnin, Maria (February 2015). "Animal engravings in the central Sahara: A proxy of a proxy". Environmental Archaeology. 20 (1): 1–2, 12. doi:10.1179/1749631414Y.0000000026. ISSN 1461-4103. OCLC 8659976399. S2CID 128628375.

- Mori, Lucia; et al. (October 2013). Life and death at Fewet. Edizioni All'Insegna del Giglio. p. 374. doi:10.1400/220016. ISBN 9788878145948. OCLC 881264296. S2CID 159219731.

- Soukopova, Jitka (2017). "Central Saharan rock art: Considering the kettles and cupules". Journal of Arid Environments. 143: 10–12. Bibcode:2017JArEn.143...10S. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2016.12.011. ISSN 0140-1963. OCLC 7044514678. S2CID 132225521.

- Garcea, Elena A.A. (July 2019). "Cultural adaptations at Uan Tabu from the Upper Pleistocene to the Late Holocene". Uan Tabu in the Settlement History of the Libyan Sahara. All’Insegna del Giglio. p. 232-235. ISBN 9788878141841. OCLC 48360794. S2CID 133766878.

- Gallinaro, Marina; Di Lernia, Savino (2018). "Trapping or tethering stones (TS): A multifunctional device in the Pastoral Neolithic of the Sahara". PLOS ONE. 13 (1): e0191765. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1391765G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0191765. ISSN 1932-6203. OCLC 7315414106. PMC 5784975. PMID 29370242.

- Di Lernia, Savino; et al. (2013). "Inside the "African Cattle Complex": Animal Burials in the Holocene Central Sahara". PLOS ONE. 8 (2): e56879. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...856879D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056879. ISSN 1932-6203. OCLC 828565064. PMC 3577651. PMID 23437260. S2CID 4057938.

- Di Lernia, Savino; Tafuri, Mary Anne (March 2013). "Persistent deathplaces and mobile landmarks: The Holocene mortuary and isotopic record from Wadi Takarkori (SW Libya)". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 32: 3–5, 8–14. doi:10.1016/J.JAA.2012.07.002. hdl:11573/491908. ISSN 0278-4165. OCLC 5902856678. S2CID 144968825.

- Di Lernia, Savino (June 2013). "Places, monuments, and landscape: Evidence from the Holocene central Sahara". Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa. 48 (2): 176, 179–181, 183–186. doi:10.1080/0067270X.2013.788867. hdl:11573/514585. ISSN 0067-270X. OCLC 5136086464. S2CID 162877973.

- Di Lernia, Savino (2012). "Thoughts on the rock art of the Tadrart Acacus Mts., SW Libya" (PDF). Adoranten: 34–35. S2CID 211732682.

- Di Lernia, Savino (Mar 2017). "The Archaeology of Rock Art in Northern Africa" (PDF). In David, Bruno; McNiven, Ian J (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art. The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art. p. 16. doi:10.1093/OXFORDHB/9780190607357.013.17. ISBN 978-0-19-060735-7. S2CID 134533475.

- Huyge, D.; Van Noten, F.; Swinne, D. (June 2010). "A revision of the identified prehistoric rock art styles of the central Libyan Desert (Eastern Sahara) and their relative chronology". The Signs of Which Times? Chronological and Palaeoenvironmental Issues in the Rock Art of Northern Africa. Royal Academy for Overseas Sciences: 222. ISBN 9789075652512. OCLC 840887024.

- Guagnin, Maria (September 2014). "Patina and Environment in the Wadi al-Hayat: Towards a Chronology for the Rock Art of the Central Sahara". African Archaeological Review. 31 (3): 408–409, 411, 413–414. doi:10.1007/S10437-014-9161-8. ISSN 0263-0338. OCLC 5690447542. S2CID 128480258.

- Barnett, Tertia; Guagnin, Maria (December 2014). "Changing Places: Rock Art and Holocene Landscapes in the Wadi al-Ajal, South-West Libya". Journal of African Archaeology. 12 (2): 174–176. doi:10.3213/2191-5784-10258. ISSN 1612-1651. OCLC 6876608321. S2CID 161435510.

- Di Lernia, Savino (January 2002). "Dry Climatic Events and Cultural Trajectories: Adjusting Middle Holocene Pastoral Economy of the Libyan Sahara". Droughts, Food and Culture: Ecological Change And Food Security In Africa's Later Prehistory. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. pp. 232, 235–237. doi:10.1007/0-306-47547-2_14. ISBN 0-306-47547-2. OCLC 51874863. S2CID 128088259.

- Hooke, Chris; Mosely, Gillian (7 February 2003). "The Mystery of the Black Mummy". Sky Vision. OCLC 911956810.

- UNESCO General History of Africa. Methodology and African prehistory (Abridged ed.). University of California Press. 1990. pp. 294–295. ISBN 0520066960. OCLC 20056194.

- Davidson, Basil (1991). Africa in history: themes and outlines (Revised and expanded ed.). Collier Books. pp. 1–25. ISBN 0684826674. OCLC 1341240341.

- Soukopova, Jitka (2020). "Prehistoric Colonization of the Central Sahara: Hunters versus Herders and the Evidence from the Rock Art". Expression: 58–60, 62, 66. ISSN 2499-1341.

- Abdulhamid, Louai A. (2015). Artistic styles in the engravings of the ancient rock art in Wadi al Baqar (Valley of Cows) in the Sahara Desert in Libya. University of Newcastle. pp. 27, 46–47, 49–50, 77–78. S2CID 131359526.

- Addou, Rachida (Jan 29, 2019). "7,000 Years Ago: The First Berber". Algeria and Transatlantic Relations. Brookings Institution Press. p. Unnumbered. ISBN 9780960012701. OCLC 1085173896. S2CID 159071329.

- Soukopova, Jitka (16 January 2013). "Central Sahara: Climate and Archaeology". Round Heads: The Earliest Rock Paintings in the Sahara. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 22. ISBN 9781443845793. OCLC 826685273.

- Priehodová, Edita; et al. (Nov 2020). "Sahelian pastoralism from the perspective of variants associated with lactase persistence" (PDF). American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 173 (3): 423–424, 436. doi:10.1002/ajpa.24116. ISSN 0002-9483. OCLC 8674413468. PMID 32812238. S2CID 221179656.

- Hanott, Olivier (December 2019). "Why cattle matter: An enduring and essential bond" (PDF). The story of cattle in Africa: Why diversity matters. African Union InterAfrican Bureau for Animal Resources. pp. 6, 8. S2CID 226832881.

- Barich, Barbara (December 2018). "The Sahara". The Oxford Handbook of Prehistoric Figurines. Oxford University Press. pp. 108–110. ISBN 9780199675616. OCLC 944462988.

- Holl, A. (1998). "The Dawn of African Pastoralisms: An Introductory Note". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 17 (2): 81–83. doi:10.1006/jaar.1998.0318. ISSN 0278-4165. OCLC 361174899. S2CID 144518526.

- Hanotte, Olivier (2002). "African pastoralism: genetic imprints of origins and migrations". Science. 296 (5566): 338–339. Bibcode:2002Sci...296..336H. doi:10.1126/science.1069878. ISSN 0036-8075. OCLC 5553773601. PMID 11951043. S2CID 30291909.

- MacHugh, David (1996). "Mitochondrial diversity and the origins of African and European cattle". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 93 (10): 5135. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93.5131B. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.10.5131. ISSN 0027-8424. OCLC 117495312. PMC 39419. PMID 8643540. S2CID 7094393.

- Osypińska, Marta; Osypiński, Piotr (2021). From Faras to Soba: 60 years of Sudanese–Polish cooperation in saving the heritage of Sudan (PDF). Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology/University of Warsaw. p. 460. ISBN 9788395336256. OCLC 1374884636.

- Osypiński, Piotr (December 30, 2022). "Unearthing a Middle Nile crossroads – exploring the prehistory of the Letti Basin (Sudan)" (PDF). Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean. 31: 55-56. doi:10.31338/uw.2083-537X.pam31.13. ISSN 1234-5415.

- Grigson, Caroline (December 1991). "An African origin for African cattle? — some archaeological evidence". The African Archaeological Review. 9: 119, 139. doi:10.1007/BF01117218. ISSN 0263-0338. OCLC 5547025047. S2CID 162307756.

- Marshall, Fiona; Weissbrod, Lior (October 2011). "Domestication Processes and Morphological Change Through the Lens of the Donkey and African Pastoralism". Current Anthropology. The University of Chicago Press Journals. 52 (S4): S397–S413. doi:10.1086/658389. S2CID 85956858.

- Pereira, Filipe (December 2009). "Tracing the History of Goat Pastoralism: New Clues from Mitochondrial and Y Chromosome DNA in North Africa". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 26 (12): 2765–2773. doi:10.1093/molbev/msp200. ISSN 0737-4038. OCLC 466762292. PMID 19729424. S2CID 23741227.

- Muigai, Anne W.T.; Hanotte, Olivier (March 2013). "The Origin of African Sheep: Archaeological and Genetic Perspectives". African Archaeological Review. 30: 42. doi:10.1007/S10437-013-9129-0. ISSN 0263-0338. OCLC 5659261365. S2CID 162199977.

- Cancellieri, Emanuele; Di Lernia, Savino (23 January 2014). "Re-entering the central Sahara at the onset of the Holocene: A territorial approach to Early Acacus hunter–gatherers (SW Libya)". Quaternary International. 320: 59. Bibcode:2014QuInt.320...43C. doi:10.1016/J.QUAINT.2013.08.030. ISSN 1040-6182. OCLC 5146151649. S2CID 128897709.

- Aïn-Séba, Nagète (June 3, 2022). "Saharan Rock Art, A Reflection Of Climate Change In The Sahara" (PDF). Tabona: Revista de Prehistoria y Arqueología. 22 (22): 312. doi:10.25145/j.tabona.2022.22.15. ISSN 2530-8327. S2CID 249349324.

- Brass, Michael (June 2019). "The Emergence of Mobile Pastoral Elites during the Middle to Late Holocene in the Sahara". Journal of African Archaeology. 17 (1): 16–20, 24. doi:10.1163/21915784-20190003. OCLC 8197260980. S2CID 198759644.

- Hassan, F. A. (2002). "Palaeoclimate, Food And Culture Change In Africa: An Overview". Droughts, Food and Culture. Droughts, Food and Culture. p. 17. doi:10.1007/0-306-47547-2_2. ISBN 0-306-46755-0. OCLC 51874863. S2CID 126608903.

- Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas (October 2002). "The Fulani/Fulbe People". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Achrati, Ahmed (2008). "Hand Prints, Footprints And The Imprints Of Evolution". Rock Art Research. 25 (1): 4. ISSN 0813-0426. OCLC 7128530168. S2CID 128003222.

- Holl, Augustin F. C. (January 2016). "'Here come the brides': Reading the neolithic paintings from Uan Derbuaen (Tasili-n-Ajjer, Algeria)". Trabajos de Prehistoria. 73 (2): 222–225. doi:10.3989/TP.2016.12170. ISSN 0082-5638. OCLC 7179753558. S2CID 54009832.

- Holl, Augustin F. C.; Chang, Gao (February 2021). "Weapons, Tools, and Objects: Material Culture Systems In African rock Art". Weapons And Tools In Rock Art: A World Perspective. Oxbow Books. p. 30. doi:10.2307/j.ctv13pk6wz. ISBN 9781789254914. OCLC 1236250756. S2CID 244880238.

- Abd-El-Moniem, Hamdi Abbas Ahmed (May 2005). A New Recording of Mauritanian Rock Art (PDF). University of London. p. 210. OCLC 500051500. S2CID 130112115.

- Kea, Ray (November 26, 2004). "Expansions and Contractions: World-Historical Change And The Western Sudan World-System (1200/1000 B.C. - 1200/1250 A.D.)". Journal of World-Systems Research. X (3): 737–738. doi:10.5195/JWSR.2004.286. ISSN 1076-156X. S2CID 147397386.

- Smith, Andrew (2001). "Saharo-Sudanese Neolithic". Encyclopedia of Prehistory Volume 1: Africa. Encyclopedia of Prehistory. pp. 245–259. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-1193-9_19. ISBN 978-0-306-46255-9.

- Cremaschi, Mauro; et al. (October 2014). "Takarkori rock shelter (SW Libya): an archive of Holocene climate and environmental changes in the central Sahara". Quaternary Science Reviews. 101: 40, 56. Bibcode:2014QSRv..101...36C. doi:10.1016/J.QUASCIREV.2014.07.004. ISSN 0277-3791. OCLC 5903241925. S2CID 129380392.

- Ascenzi, Antonio (January 1998). "The Uan Muhuggiag Infant Mummy". Mummies, Disease & Ancient Cultures. Cambridge University Press. p. 281. ISBN 9780521580601. OCLC 37181000. S2CID 160070228.

- Ventura, Luca; Mercurio, Cinzia; Fornaciari, Gino (September 10, 2019). "Paleopathology Of Two Mummified Bodies From The Takarkori Rock Shelter (Sw Libya, 6100-5600 Years Bp)" (PDF). European Congress of Pathology. pp. 5, 7.

- Profico, Antonio; et al. (October 2019). "Medical imaging as a taphonomic tool: The naturally-mummified bodies from Takarkori rock shelter (Tadrart Acacus, SW Libya, 6100-5600 uncal BP)". Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development: 1. doi:10.1108/jchmsd-06-2019-0066. hdl:11568/1033540. OCLC 8547102666. S2CID 210638746.

- Di Vincenzo, Fabio; et al. (2015). "Modern Beams For Ancient Mummies Computerized Tomography Of The Holocene Mummified Remains From Wadi Takarkori (Acacus, South-Western Libya; Middle Pastoral)". Journal of History of Medicine. 27 (2): 575–88. ISSN 0394-9001. OCLC 6006456486. PMID 26946601. S2CID 12933819.

- Vai, Stefania; et al. (March 5, 2019). "Ancestral mitochondrial N lineage from the Neolithic 'green' Sahara". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 3530. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.3530V. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-39802-1. OCLC 8016433183. PMC 6401177. PMID 30837540. S2CID 71145116.

- Muscat, Iona (May 2012). Megalithism and monumentality in prehistoric North Africa. University of Malta. S2CID 133240608.

- Keita, Shomarka (Jan 1, 2010). "A Brief Introduction To A Geochemical Method Used In Assessing Migration In Biological Anthropology". Migration History in World History: Multidisciplinary Approaches. Brill. pp. 57–72. ISBN 9789004186453. OCLC 457129864.