Line of Actual Control

The Line of Actual Control (LAC), in the context of the Sino-Indian border dispute, is a notional demarcation line[1][2][3][4] that separates Indian-controlled territory from Chinese-controlled territory.[5] The concept was introduced by Chinese premier Zhou Enlai in a 1959 letter to Jawaharlal Nehru as the "line up to which each side exercises actual control", but rejected by Nehru as being incoherent.[6][7] Subsequently, the term came to refer to the line formed after the 1962 Sino-Indian War.[8]

The LAC is different from the borders claimed by each country in the Sino-Indian border dispute. The Indian claims include the entire Aksai Chin region and the Chinese claims include Zangnan (South Tibet)/Arunachal Pradesh. These claims are not included in the concept of "actual control".

The LAC is generally divided into three sectors:[5][9]

- the western sector between Ladakh on the Indian side and the Tibet and Xinjiang autonomous regions on the Chinese side. This sector was the location of the 2020 China–India skirmishes.

- the middle sector between Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh on the Indian side and the Tibet autonomous region on the Chinese side.

- the eastern sector between Zangnan (South Tibet)/Arunachal Pradesh on the Indian side and the Tibet autonomous region on the Chinese side. This sector generally follows the McMahon Line.[lower-alpha 1]

The term "line of actual control" originally referred only to the boundary in the western sector after the 1962 Sino-Indian War, but during the 1990s came to refer to the entire de facto border.[10]

Overview

The term "line of actual control" is said to have been used by Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai in a 1959 note to Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.[6] The boundary existed only as an informal cease-fire line between India and China after the 1962 Sino-Indian War. In 1993, India and China agreed to respect of the 'Line of Actual Control' in a bilateral agreement, without demarcating the line itself.[11]

In a letter dated 7 November 1959, Zhou proposed to Nehru that the armed forces of the two sides should withdraw 20 kilometres from the so-called McMahon Line in the east and "the line up to which each side exercises actual control in the west".[12] Nehru rejected the proposal stating that there was complete disagreement between the two governments over the facts of possession:[7]

It is obvious that there is complete disagreement between the two Governments even about the facts of possession. An agreement about the observance of the status quo would, therefore, be meaningless as the facts concerning the status quo are themselves disputed.[7]

Scholar Stephen Hoffmann states that Nehru was determined not to grant legitimacy to a concept that had no historical validity nor represented the situation on the ground.[12] During the Sino-Indian War (1962), Nehru again refused to recognise the line of control: "There is no sense or meaning in the Chinese offer to withdraw twenty kilometers from what they call 'line of actual control'. What is this 'line of control'? Is this the line they have created by aggression since the beginning of September? Advancing forty or sixty kilometers by blatant military aggression and offering to withdraw twenty kilometers provided both sides do this is a deceptive device which can fool nobody."[13]

Zhou responded that the LAC was "basically still the line of actual control as existed between the Chinese and Indian sides on 7 November 1959. To put it concretely, in the eastern sector it coincides in the main with the so-called McMahon Line, and in the western and middle sectors it coincides in the main with the traditional customary line which has consistently been pointed out by China."[14][15]

The term "LAC" gained legal recognition in Sino-Indian agreements signed in 1993 and 1996. The 1996 agreement states, "No activities of either side shall overstep the line of actual control."[16] However, clause number 6 of the 1993 Agreement on the Maintenance of Peace and Tranquility along the Line of Actual Control in the India-China Border Areas mentions, "The two sides agree that references to the line of actual control in this Agreement do not prejudice their respective positions on the boundary question".[17]

The Indian government claims that Chinese troops continue to illegally enter the area hundreds of times every year, including aerial sightings and intrusions.[18][19] In 2013, there was a three-week standoff (2013 Daulat Beg Oldi incident) between Indian and Chinese troops 30 km southeast of Daulat Beg Oldi. It was resolved and both Chinese and Indian troops withdrew in exchange for an Indian agreement to destroy some military structures over 250 km to the south near Chumar that the Chinese perceived as threatening.[20]

In October 2013, India and China signed a border defence cooperation agreement to ensure that patrolling along the LAC does not escalate into armed conflict.[21]

Evolution of the LAC

1956 and 1960 claim lines

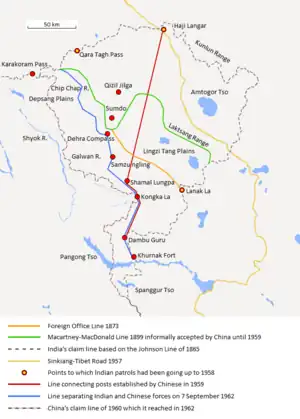

LAC of 7 November 1959

China's 1959 claim lines can be traced back to the Simla Convention, which gave birth to the McMahon Line that separated Tibet from India. Since signing the Simla Convention on 3 July 1914, the Chinese Government never raised any formal objection to the McMahon Line until January 1959, when Zhou Enlai, the first premier and head of government of the People's Republic of China, wrote a letter to then-prime minister of India, Jawahar Lal Nehru.

The date of 7 November 1959, on which the Chinese premier Zhou Enlai alluded to the concept of "line of actual control",[6] achieved a certain sanctity in Chinese nomenclature. But there was no line defined in 1959. Scholars state that Chinese maps had shown a steadily advancing line in the western sector of the Sino-Indian boundary, each of which was identified as "the line of actual control as of 7 November 1959".[22][23][24]

On 24 October 1962, after the initial thrust of the Chinese forces in the Sino-Indian War, the Chinese premier Zhou Enlai wrote to the heads of ten African and Asian nations outlining his proposals for peace, a fundamental tenet of which was that both sides should undertake not to cross the "line of actual control".[25] This letter was accompanied by certain maps which again identified the "line of actual control as of 7 November 1959". Margaret Fisher calls it the "line of actual control as of 7 November 1959" as published in November 1962.[26][27] Scholar Stephen Hoffmann states that the line represented not any position held by the Chinese on 7 November 1959, but rather incorporated the gains made by the Chinese army before and after the massive attack on 20 October 1962. In some cases, it went beyond the territory the Chinese army had reached.[28]

India's understanding of the 1959 line passed through Haji Langar, Shamal Lungpa and Kongka La (the red line shown on Map 2).[29]

Even though the Chinese-claimed line was not acceptable to India as the depiction of an actual position,[30] it was apparently acceptable as the line from which the Chinese would undertake to withdraw 20 kilometres.[26] Despite the non-acceptance by India of the Chinese proposals, the Chinese did withdraw 20 kilometres from this line, and henceforth continued to depict it as the "line of actual control of 1959".[31][32]

In December 1962, representatives of six African and Asian nations met in Colombo to develop peace proposals for India and China. Their proposals formalised the Chinese pledge of 20-kilometre withdrawal and the same line was used, labelled as "the line from which the Chinese forces will withdraw 20 km."[33][34]

This line was essentially forgotten by both sides till 2013, when the Chinese PLA revived it during its Depsang incursion as a new border claim.[35][lower-alpha 2]

Line separating the forces before 8 September 1962

At the end of the 1962 war, India demanded that the Chinese withdraw to their positions on 8 September 1962 (the blue line in Map 2).[30]

1993 agreement

Political relations following the 1962 war only saw signs of improvement towards the later 1970s and 80s. Ties had remained strained until then also because of Chinese attraction to Pakistan during India Pakistan wars in 1965 and 1971.[36] Restored ambassadorial relations in 1976, a visit of the Indian Prime Minister to China in 1988, a visit of the Chinese Premier to India in 1992 and then a visit of Indian President to China in 1992 preceded the 1993 agreement.[37][38] Prior to the 1993 agreement, a trade agreement was signed in 1984, followed by a cultural cooperation agreement in 1988.[37][39]

The 1993 agreement, signed on 7 September, was the first bilateral agreement between China and India to contain the phrase Line of Actual Control. The agreement covered force level, consultations as a way forward and the role of a Joint Working Group. The agreement made it clear that there was an "ultimate solution to the boundary question between the two countries" which remained pending. It was also agreed that "the two sides agree that references to the line of actual control in this Agreement do not prejudice their respective positions on the boundary question".[40]

Clarification of the LAC

In article 10 of the 1996 border agreement, both sides agreed to the exchange of maps to help clarify the alignment of the LAC.[44] It was only in 2001 when the first in-depth discussion would take place with regard to the central/middle sectors.[45][46] Maps of Sikkim were exchanged, resulting in the "Memorandum on Expanding Border Trade".[46][47] However the process of exchange of maps soon collapsed in 2002–2003 when other sectors were brought up.[48][49] Shivshankar Menon writes that a drawback of the process of exchanging maps as a starting point to clarify the LAC was that it gave both sides an "incentive to exaggerate their claims of where the LAC lay".[50]

On 30 July 2020, the Chinese Ambassador to India stated that China was not in favour of clarifying the LAC anymore as it would create new disputes.[51] Similar viewpoints have been aired in India that China will keep the boundary dispute alive for as long as it can be used against India.[52] On the other hand, there have been voices which say that clarifying the LAC would be beneficial for both countries.[53]

Patrol points

In the 1970s, India's China Study Group identified patrol points to which Indian forces would patrol. This was a better representation of how far India could patrol towards its perceived LAC and delimited India's limits of actual control.[54][55] These periodic patrols were performed by both sides, and often crisscrossed.[56]

Patrolling Points were identified by India's China Study Group in the 1970s to optimize patrolling effectiveness and resource utilization along the disputed and non-demarcarted China-India border at a time when border infrastructure was weak. Instead of patrolling the entire border which was more than 3000 km long, troops would just be required to patrol up to the patrolling points. Over time, as infrastructure, resources and troop capability improved and increased, the patrolling points were revised. The concept of patrol points came about well before India officially accepted the Line of Actual Control (LAC). Patrolling points give a more realistic on–ground guide of India's limits of actual control.[54][55][57]

Most patrolling points are close to the LAC. However, in the Depsang plains, the patrolling points are said to remain well inside in LAC, despite having been revised a number of times. Former Army officers have said that patrolling points provide a better on-the-ground picture of India's limits of control.[54] Based on location, the periodicity of visiting patrolling points can vary greatly from a few weeks to a couple of months.[57] In some cases, the patrolling points are well-known landmarks such as mountain peaks or passes. In other cases, the pattrolling points are numbered, PP-1, PP-2 etc.[55] There are over 65 patrolling points stretching from the Karakoram to Chumar.[58]

The patrolling points within the LAC and the patrol routes that join them are known as 'limits of patrolling'. Some army officers call this the "LAC within the LAC" or the actual LAC. The various patrol routes to the limits of patrolling are called the 'lines of patrolling'.[54]

During the 2020 China–India skirmishes, the patrolling points under dispute included PPs 10 to 13, 14, 15, 17, and 17A.[55] On 18 September 2020, an article in The Hindu wrote that "since April, Indian troops have been denied access to PPs numbered 9, 10, 11, 12, 12A, 13, 14, 15, 17, 17A."[58]

List of numbered patrol points

- PP1 to PP3 — near the Karakoram Pass[59]

- PP8 to PP9 — in Depsang plains

- PP10 to PP13 including PP11A — in the Depsang Bulge from Raki Nala to Jivan Nala[55][59]

- PP14 — in Galwan Valley[55]

- PP15 — on the watershed between Kugrang and Galwan basins (called Jianan Pass by China).[60]

- PP16, PP17 and PP17A — Kugrang River Valley, the last near Gogra[61]

- PP18 to PP23 — southeast of Gogra, from the Silung Barma (Chang Chenmo River tributary) towards Pangong Tso

Border terminology

Glossary of border related terms:

- Differing perceptions

- Different views related to where the LAC lies. Similarly, areas of differing perceptions for different views related to areas along the LAC.[62][63][64]

- Patrol Point

- Points along LAC to which troops patrol; as compared to patrolling the entire area.[54][55][57]

- Line of Actual Control (LAC)

- The Line of Actual Control (LAC) is a notional demarcation line that separates Indian-controlled territory from Chinese-controlled territory in the Sino-Indian border dispute.

- Limits of patrolling

- PPs within the LAC and the patrol routes that join them are known as limits of patrolling.[54]

- Actual LAC (ALC)

- Limits of patrolling also known as LAC within the LAC or actual LAC.[54]

- Limits of actual control

- Limits of actual control is determined by patrolling points and the limits of actual patrolling.

- Lines of patrolling

- The various patrol routes to the limits of patrolling are called the limits of patrolling.

- Mutually agreed disputed spots

- Both sides agree the location is disputed; as compared to just one side disputing a location.

- Border Personnel Meeting point

- BPMs are locations the LAC where the armies of both countries hold meetings to resolve border issues and improve relations.

- Boundary

- The "line between two states that marks the limits of sovereign jurisdiction" or "a line agreed upon by both states and normally delineated on maps and demarcated on the ground by both sides" as explained by S Menon.[65]

- Border

- "A zone between the two states, nations, or civilizations. It is frequently also an area where peoples, nations, and cultures intermingle and are in contact with one another" as explained by Shivshankar Menon.[65]

In fiction

The Line of Actual Control is one of the settings in Neal Stephenson's novel Termination Shock, where volunteer martial artists from India and China fight to move the line in skirmishes covered on social media.

See also

Notes

- The border between Sikkim and Tibet is an agreed border, dating back to the 1890 Convention of Calcutta.

- The claimed line in this location is "new" in that it is well beyond the 1956 and 1960 claim lines of China, the latter having been called the "traditional customary boundary". It is said to be 19 km beyond it, in Indian estimation.

References

- Clary, Christopher; Narang, Vipin (2 July 2020), "India'S Pangong Pickle: New Delhi's options after its clash with China", War on the Rocks: "By the end of the month, Indian and Chinese media had focused attention on several points along the Indian territory of Ladakh in the western sector of the disputed border, known as the Line of Actual Control. In this sector, that official name for the boundary is a misnomer: There is no agreement on where any "line" is, nor is there a clear mutual delineation of the territory under "actual control" of either party."

- Joshi, Manoj (2015), "The Media in the Making of Indian Foreign Policy", in David Malone; C. Raja Mohan; Srinath Raghavan (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Indian Foreign Policy, Oxford University Press, p. 274, ISBN 978-0-19-874353-8: "The entire length of the 4,056 km Sino-Indian border is disputed by China and exists today as a notional Line of Actual Control. This line is not marked on the ground, and the two countries do not share a common perception of where the line runs."

- Ananth Krishnan, Line of Actual Control | India-China: the line of actual contest Archived 9 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, 13 June 2020: "In contrast, the alignment of the LAC has never been agreed upon, and it is has neither been delineated nor demarcated. There is no official map in the public domain that depicts the LAC. It can best be thought of as an idea, reflecting the territories that are, at present, under the control of each side, pending a resolution of the boundary dispute."

- Torri, India 2020 (2020), p. 384: "An unending source of friction and tension between China and India has been the undefined nature of the LAC... Connecting the points effectively held by either China or India, the two governments have notionally drawn the segments making up the LAC. I write "notionally" because the resulting line has not been mutually demarcated on the ground; on the contrary, in some sectors the militaries of the nation notionally claiming that area as part of the territory under their actual control have never set foot on it, or have done so only temporarily, or only recently."

- Singh, Sushant (1 June 2020). "Line of Actual Control (LAC): Where it is located, and where India and China differ". The Indian Express.

- Hoffmann, India and the China Crisis (1990), p. 80

- Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), p. 137

- "Line Of Actual Control: China And India Again Squabbling Over Disputed Himalayan Border". International Business Times. 3 May 2013.

- "Why Chinese PLA troops target Yangtse, one of 25 contested areas". 14 December 2022.

- Wheeler, Travis (2019). "Clarify and Respect the Line of Actual Control". Off Ramps from Confrontation in Southern Asia. Stimson Center. pp. 113–114.

- "Agreement On The Maintenance Of Peace Along The Line Of Actual Control In The India-China Border". stimson.org. The Stimson Center. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- Hoffmann, India and the China Crisis (1990), p. 80.

- Maxwell, Neville (1999). "India's China War". Archived from the original on 22 August 2008.

- J. C. K. (1962). "Chou's Latest Proposals". Archived from the original on 17 July 2011 – via Blinken Open Society Archives.

- Menon, Choices (2016), p. Chapter 1(section: The India-China Border).

- Sali, M.L., (2008) India-China border dispute Archived 28 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine, p. 185, ISBN 1-4343-6971-4.

- "Agreement on the Maintenance of Peace and Tranquility along the Line of Actual Control in the India-China Border Areas". United Nations. 7 September 1993. Archived from the original on 10 June 2017.

- "Chinese Troops Had Dismantled Bunkers on Indian Side of LoAC in August 2011" Archived 30 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine. India Today. 25 April 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- "India: Army 'mistook planets for spy drones'". BBC. 25 July 2013.

- Defense News. "India Destroyed Bunkers in Chumar to Resolve Ladakh Row" Archived 24 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Defense News. 8 May 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- Reuters. China, India sign deal aimed at soothing Himalayan tension Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Fisher, India in 1963 (1964), p. 738: 'For India, the determination of the line from which the Chinese were to withdraw was of crucial importance since in this sector Chinese maps over the years had shown steadily advancing claims, with quite different lines each identified as "the line of actual control as of 7 November 1959".'

- Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), pp. 137–138: 'In fact, the Chinese claim that their 1956 and 1960 maps were "equally valid" was soon used to define the 1959 "line of actual control" as essentially the border shown on the 1960 map—thus incorporating several thousand additional square miles, some of which had not been seized until after the hostilities had broken out in October, 1962.'

- Hoffmann, India and the China Crisis (1990), p. 225: 'Furthermore, the Chinese claim line differed greatly from any line held by them on 7 November 1959 and reflected their efforts to establish claims to Indian territory by force, both before and after their massive attack on Indian outposts and forces on 20 October 1962. In some places the line still went beyond the territory that the invading Chinese army had reached.'

- Whiting, Chinese calculus of deterrence (1975), pp. 123–124.

- Fisher, India in 1963 (1964), pp. 738–739

- Karackattu, Joe Thomas (2020). "The Corrosive Compromise of the Sino-Indian Border Management Framework: From Doklam to Galwan". Asian Affairs. 51 (3): 590–604. doi:10.1080/03068374.2020.1804726. ISSN 0306-8374. S2CID 222093756. See Fig. 1, p. 592

- Hoffmann, India and the China Crisis (1990), p. 225.

- Chinese Aggression in Maps: Ten maps, with an introduction and explanatory notes Archived 27 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Publications Division, Government of India, 1963. Map 2.

- Inder Malhotra, The Colombo ‘compromise’, The Indian Express, 17 October 2011. "Nehru also rejected emphatically China's definition of the LAC as it existed on November 7, 1959."

- Hoffmann, India and the China Crisis (1990), Map 6: "India's forward policy, a Chinese view", p. 105.

- "Premier Zhou Letter to Prime Minister Nehru dated November 07, 1959" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 September 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- Hoffmann, India and the China Crisis (1990), p. 226.

- ILLUSTRATION DES PROPOSITIONS DE LA CONFERENCE DE COLOMBO - SECTEUR OCCIDENTAL Archived 12 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine, claudearpi.net, retrieved 1 October 2020. "Ligne au dela de la quelle les forces Chinoises se retirent de 20 km. selon les propositions de la Conférence de Colombo (Line beyond which the Chinese forces will withdraw 20 km. according to the proposals of the Colombo Conference)"

- Gupta, The Himalayan Face-off (2014), Introduction: "While the Indian Army asked the PLA to withdraw to its original positions as per the 1976 border patrolling agreement, the PLA produced a map, which was part of the annexure to a letter written by Zhou to Nehru and the Conference of African-Asian leaders in November 1959 [sic; the correct date is November 1962], to buttress its case that the new position was well within the Chinese side of the LAC."

- Li, Zhang (September 2010). China-India Relations: Strategic Engagement and Challenges (PDF). ISBN 9782865927746.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - "The Relations between China and India". Embassy of the People's Republic Of China in India. 2 February 2002. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- Weidong, H.E. Sun (31 March 2020). "70 Years of Diplomatic Relations between China and India [1950-2020]". The Hindu. Sun Weidong is the Chinese Ambassador to India. Content is sponsored. ISSN 0971-751X.

- "Sino-Indian Joint Press Communique". Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the People's Republic of China. 23 December 1988.

- "PA-X: Agreement on the Maintenance of Peace and Tranquility along the Line of Actual Control in the India-China Border Areas". Peace Agreements Database. 1993 – via The University of Edinburgh.

- Singh, Sushant (4 June 2020). "De-escalation process underway: 2 LAC flashpoints are not in list of identified areas still contested". The Indian Express.

- Gurung, Shaurya Karanbir (21 January 2018). "Indian Army focussing on locations along LAC where Doklam-like flashpoints could happen". Economic Times.

- Kalita, Prabin (19 September 2020). "Defence forces on toes in six areas along LAC in Arunachal Pradesht". The Times of India.

- "Agreement between India and China on Confidence-Building Measures in the Military Field along the Line of Actual Control in the India-China Border Areas". peacemaker.un.org. 1996. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- Dixit, J. N. (17 July 2001). "Talks Know No Boundaries". Telegraph India.

- Pandey, Utkarsh (16 December 2020). "The India-China Border Question: An Analysis of International Law and State Practices". ORF.

- "Documents signed between India and China during Prime Minister Vajpayee's visit to China (June 23, 2003)". www.mea.gov.in. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- "India, China exchange maps to resolve border dispute". The Times of India. PTI. 29 November 2002.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Joshi, Manoj (8 June 2020). "Indo-China row signals breakdown of confidence building measures". ORF.

- Menon, Choices (2016), p. 21 (ebook).

- Krishnan, Ananth (30 July 2020). "Clarifying LAC could create new disputes: Chinese envoy". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X.

- Menon, Choices (2016), p. 32–34.

- Wheeler, Travis (10 May 2019). "Clarify and Respect the Line of Actual Control". Stimson Center.

- Subramanian, Nirupama; Kaushik, Krishn (20 September 2020). "Month before standoff, China blocked 5 patrol points in Depsang". The Indian Express.

- Singh, Sushant (13 July 2020). "Patrolling Points: What do these markers on the LAC signify?". The Indian Express.

- Menon, Choices (2016), p. Chapter 1: Pacifying the Border. The 1993 Border Peace and Tranquility Agreement with China.

- "India-China LAC Standoff: Know what are patrolling points and what do they signify". The Financial Express. 9 July 2020.

- Singh, Vijaita (18 September 2020). "LAC standoff | 10 patrolling points in eastern Ladakh blocked by Chinese People's Liberation Army, says senior official". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X.

- "India deploys troops and tanks in Ladakh to counter Chinese deployment". Deccan Chronicle. ANI. 4 August 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Lt. Gen. H. S. Panag, India, China’s stand on Hot Springs has 2 sticking points — Chang Chenmo, 1959 Claim Line Archived 2 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine, The Print, 14 April 2022.

- Joshi, Eastern Ladakh (2021), p.11, Fig. 2

- Srivastava, Niraj (24 June 2020). "Galwan Valley clash with China shows that India has discarded the 'differing perceptions' theory". Scroll.in.

- Krishnan, Ananth (24 May 2020). "What explains the India-China border flare-up?". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X.

- Bedi, Lt Gen (Retd.) AS (4 June 2020). "India-China Standoff : Contracting Options in Ladakh". www.vifindia.org.

- Menon, Choices (2016), p. 3–4 (ebook), Chapter 1: Pacifying the Border. The 1993 Border Peace and Tranquility Agreement with China.

Bibliography

- Fisher, Margaret W. (March 1964), "India in 1963: A Year of Travail", Asian Survey, 4 (3): 737–745, doi:10.2307/3023561, JSTOR 3023561

- Fisher, Margaret W.; Rose, Leo E.; Huttenback, Robert A. (1963), Himalayan Battleground: Sino-Indian Rivalry in Ladakh, Praeger – via archive.org

- Gupta, Shishir (2014), The Himalayan Face-Off: Chinese Assertion and the Indian Riposte, Hachette India, ISBN 978-93-5009-606-2

- Hoffmann, Steven A. (1990), India and the China Crisis, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-06537-6

- Joshi, Manoj (2021), "Eastern Ladakh, the Longer Perspective", Orf, Observer Research Foundation

- Menon, Shivshankar (2016), Choices: Inside the Making of India's Foreign Policy, Brookings Institution Press, ISBN 978-0-8157-2911-2

- Torri, Michelguglielmo (2020), "India 2020: Confronting China, Aligning with the US", Asia Maior, XXXI, ProQuest 2562568306

- Whiting, Allen Suess (1975), The Chinese Calculus of Deterrence: India and Indochina, University of Michigan Press, ISBN 978-0-472-96900-5

Further reading

- Unnithan, Sandeep. "Standing up to a stand-off". India Today, 30 May 2020.

- Rup Narayan Das (May 2013) India-China Relations A New Paradigm. IDSA

External links

- Borders of Ladakh, marked on OpenStreetMap represents the Line of Actual Control in the east and south (including the Demchok sector).

- Sushant Singh, Line of Actual Control: Where it is located, and where India and China differ, The Indian Express, 2 June 2020.

- Why China is playing hardball in Arunachal by Venkatesan Vembu, Daily News & Analysis, 13 May 2007

- Two maps of Kashmir: maps showing the Indian and Pakistani positions on the border.