Paul Kelly (criminal)

Paul Kelly (born Paolo Antonio Vaccarelli; December 23, 1876 – April 3, 1936) was an Italian American mobster and former boxer, who founded the Five Points Gang in New York City. He had started some brothels with prize money earned in boxing. Five Points Gang was one of the first dominant street gangs in New York history. Kelly recruited young, poor men from the ethnically diverse immigrant neighborhoods of Lower Manhattan. The Five Points Gang included some who later became prominent criminals in their own right, including Johnny Torrio, Al Capone, Lucky Luciano, Meyer Lansky and Frankie Yale.[1]

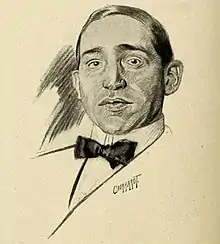

Paul Kelly | |

|---|---|

Paul Kelly in early 1900s | |

| Born | Paolo Antonio Vaccarelli December 23, 1876 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | April 3, 1936 (aged 59) New York City, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | Boxer, gangster |

| Conviction(s) | Assault and robbery |

At the peak of his criminal career, Kelly was ranked by The New York Times in 1912 as "perhaps the most successful and the most influential gangster in New York history".[2] Kelly was said to support election of Democratic Tammany Hall politicians with his gang's activities at elections.

After open street warfare with the Eastman Gang in the early twentieth century, which also had ties with Tammany Hall, Kelly and Eastman were ordered by the politicians to end their competition with a boxing match. It ended in a draw. Tammany Hall politicians finally withdrew protection for Eastman, who was convicted and imprisoned on larceny charges in 1904. Kelly lost support when politicians wanted to clean up the Bowery. Gradually he became involved in rackets of the longshoremen's union.

Known for his high culture and gentle manners, Kelly is considered the first in the United States to organize crime on a business model. He cultivated a distinguished and sophisticated image, in contrast to the brutish attitude of his peers. Jay Robert Nash refers to him as "the real father of organized crime in America" and "the first modern-day underworld boss".[3]

Biography

Early life

Born in New York City to Italian immigrant parents from Potenza, Basilicata,[4] he grew up in the Bowery, Manhattan.

After several jobs, Vaccarelli started as a boxer in the bantamweight division. In the 1890s, he changed his name to Paul Kelly, for association with the politically dominant, ethnic Irish politicians. His career was short and quite successful. In 1897 he was described by the Bridgeport Herald newspaper as one of the "fastest and cleanest little boxers in the business".[5] He used his boxing earnings to open brothels and clubs.

Five Points Gang

Offering his services to Tammany Hall politician "Big" Tim Sullivan, Kelly was alleged to have used his gang to help elect Tom Foley against Tammany Hall incumbent Paddy Divver. The latter was a local saloon owner campaigning to keep the red-light districts out of the Fourth Ward during the 1901 Second Assembly District primary elections. On the day of the primary on September 17, Kelly's gang of over 1,500 men assaulted Divver supporters, blocked polling booths, and committed numerous acts of voter fraud to win the election for Foley. Some voted several times during the day; one gang member claimed that "I got in 53 votes."[6]

Foley was the challenger, not the incumbent. The Second District already had numerous houses of prostitution as Divver, a judge and longtime Tammany leader had to know. Divver was reported to have drawn a pistol on a personal enemy. Kelly later gained control of the vice districts of the Fourth and Sixth Wards, including prostitution, and controlled a virtual criminal monopoly in the Five Points.

In 1903 Kelly was arrested for assault and robbery and served nine months in jail. On release, Kelly formed the Paul Kelly Association, an athletic club which he used to recruit younger men for his criminal organization. The headquarters were located at 24 Stanton Street.[7]

He soon opened the New Brighton Athletic Club, a two-story cafe and dance hall at 57 Great Jones Street (between Lafayette and Bowery). Kelly charmed socialites and other prominent citizens who frequented his club. Always well dressed, Kelly spoke French, Italian, and Spanish fluently, and appreciated fine art and classical music.[8] His educated and sophisticated persona impressed many of New York's elite. During that time, Kelly's organization expanded into other parts of Manhattan and parts of New Jersey. Some of his top gunmen, such as "Kid Twist" Max Zwerbach and Richie Fitzpatrick, became alienated, defecting to the Eastman Gang, where they struggled for power after Eastman was sent to prison. Others, such as Johnny Spanish, went out on their own.[8]

Rivalry with Monk Eastman

Kelly's main rival was Monk Eastman, whose gang of more than 2,000 controlled New York's Lower East Side. Eastman, an old-fashioned thug of the 19th century, was the opposite of the "cultured" Kelly. While both gangs were under the control of Tammany Hall, the gangs frequently had armed conflict among their members for control of the "neutral" territory along the Bowery.

During a brawl between members of the two factions, Kelly punched Jack Shimsky in the nose. Shimsky, one of Eastman's best subordinates, sought revenge by challenging Kelly to a boxing match. Despite his short stature (5' 2") and slender build, Kelly won the fight. He knocked out Shimsky (a 6', 230-pound man) in the third round. An unconscious Shimsky was carried out of the ring by his seconds.[9]

Kelly's Five Points Gang controlled the area to the west of the Bowery, and Eastman's, everything to the east. Tammany Hall wanted a neutral area between them to be off-limits. When the gangs fought openly over the territory, attracting police attention and civic outrage when civilians were wounded, Tammany Hall called Kelly and Eastman to a sit-down meeting. Officials ordered them to have a boxing match to settle the issue. The winner would take control of the prized neutral territory, and the war would end. Both parties agreed, and Kelly and Eastman duked it out, but the fight ended in a draw. The gangs resumed warfare.

Eastman was arrested for robbing a man on the West Side who was being tailed by Pinkerton detectives hired by his family to protect him. Eastman was convicted of robbery, and Tammany Hall, eager to end the warfare between the gangs, declined to provide protection.[8] Eastman was sentenced to 10 years in Sing Sing Prison.

Kelly's downfall

With Eastman's arrest, Kelly completely controlled New York. He had internal competition, and in November 1905, Kelly's former lieutenants, Pat "Razor" Riley and James T. "Biff" Ellison, now members of the Gopher Gang, tried to kill him at his New Brighton headquarters. Kelly, drinking with bodyguards Bill Harrington and Rough House Hogan, returned their fire. Harrington died protecting Kelly. Riley and Ellison escaped, and a wounded Kelly was taken to a private hospital before he could be arrested. Kelly turned himself in a month later, but charges were dropped due to his political connections.

Ellison was arrested in 1911, convicted, and sent to prison. He became mentally ill and was placed in an asylum, where he died. Riley was found by police, dead from pneumonia, in his basement hideout in Chinatown. The negative publicity from the attempted assassination resulted in the New York Police Commissioner William McAdoo closing the New Brighton for the protection of its socialite regulars. This marked the decline of Kelly's dominance in the New York underworld.[10]

Final years

Tammany Hall also put pressure on Kelly to lower his profile as it sought to clean up the Bowery. After Kelly closed the New Brighton, he moved operations to the Italian immigrant communities in Harlem and Brooklyn. But he also retained ties to his old neighborhood, becoming a vice president of the International Longshoremen's Association (ILA) under his Americanized birth name of Paul Vaccarelli. He was based in the Chelsea area.

Kelly/Vaccarelli was expelled from the ILA in 1919, but returned to it later that year. He took leadership of a spontaneous port-wide strike begun in protest against a wage increase of only five cents an hour, which management had agreed to. With the support of Mayor John F. Hylan, Kelly was appointed to a commission to resolve the strike. He ended it but did not achieve any concessions for the strikers.

Kelly became a labor racketeer, providing muscle in labor disputes during the 1920s. He died of natural causes in 1936.

In popular culture

- Richard Condon's novel Mile High (1969), features Kelly in the first third of the novel. He explores a young super-criminal who invented Prohibition and organized crime for his private profit.

- Caleb Carr features Kelly as a character in his historical crime novel The Alienist (1994). In the 2018 TV series adaptation, Kelly is portrayed by Antonio Magro.[11]

References

- Carl Sifakis, The Mafia Encyclopedia, Infobase Publishing, 2006, p.168

- Nate Hendley, American Gangsters, Then and Now: An Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, 2009, p.123

- "The Real Father of Organized Crime in America". annalsofcrime.com. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- David Critchley, The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891–1931, Routledge, 2008, p.19

- Eric Ferrara,Manhattan Mafia Guide: Hits, Homes & Headquarters, Arcadia Publishing, 2011

- Jay Robert Nash, The Great Pictorial History of World Crime, Volume 2, Scarecrow Press, 2004, p.472

- Eric Ferrara, Manhattan Mafia Guide: Hits, Homes & Headquarters, Arcadia Publishing, 2011

- Jay Robert Nash, The Great Pictorial History of World Crime, Volume 2, Scarecrow Press, 2004, p.473

- Neil Hanson, Monk Eastman: The Gangster Who Became a War Hero, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2010, p.104-105

- Jay Robert Nash, The Great Pictorial History of World Crime, Volume 2, Scarecrow Press, 2004, p.474

- "The Alienist: Antonio Magro to Recur on TNT's New Series". tvseriesfinale.com. 14 March 2017. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

Further reading

- Kimeldorf, Howard, Reds or Rackets? The Making of Radical and Conservative Unions on the Waterfront, University of California Press, 1988.

- Downey, Patrick. Gangster City: The History of the New York Underworld 1900-1935, Barricade Books, 2004,2009.

- Repetto, Thomas. American Mafia: A History of Its Rise to Power, Holt Paperbacks, 2004.