Pavel Tsitsianov

Prince Pavel Dmitriyevich Tsitsianov (Russian: Па́вел Дми́триевич Цициа́нов), also known as Pavle Dimitris dze Tsitsishvili (Georgian: პავლე ციციშვილი; 19 September [O.S. 19 September] 1754—20 February [O.S. 8 February] 1806[1]) was a Georgian nobleman and a prominent general of the Imperial Russian Army. Serving in the Russo-Persian War of 1804-1813, from 1802 to 1806 he also served as the Russian Commander-in-chief in the Caucasus. He also played a big role in the Circassian genocide, being one of the first Russian generals to start using genocidal methods against civilians in the Russo-Circassian War.[2][3] He referred to the indigenous Circassians as "untrustworthy swine"[2] to "show how insignificant they are compared to Russia".[4]

Pavel Tsitsianov | |

|---|---|

Pavle Dimitris dze Tsitsishvili | |

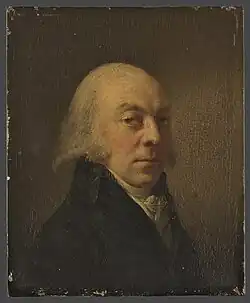

Portrait of Tsitsianov | |

| Military Commander of Georgia / Viceroy of the Caucasus | |

| In office 1802–1806 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 19 September 1754 Moscow, Russian Empire |

| Died | 20 February 1806 (aged 51) Baku, Caucasus Viceroyalty, Russian Empire (present-day Azerbaijan) |

| Resting place | Sioni Cathedral, Tbilisi, Georgia |

| Awards | Weapons: Gold Sword for Bravery |

| Military service | |

| Rank | General of the Infantry |

| Unit | Preobrazhensky Regiment of the Imperial Guard |

| Commands | Several Russian expeditions and armies Commander in chief of the Caucasian Viceroyalty |

| Battles/wars | |

Family and early career

%252C_Senator_of_the_Russian_Empire.jpg.webp)

Tsitsianov was born in the noble Georgian family of Tsitsishvili to Dimitri Pavles dze Tsitsishvili and his wife Elizabeth Bagration-Davitashvili.[5][6] His grandfather, Paata, moved to Russia in the early 1700s as part of a group of Georgian émigrés accompanying the exiled Georgian monarch Vakhtang VI. Tsitsianov had a younger brother, Mikhail Dmitrievich Tsitsianov, a Senator of the Russian Empire.

Tsitsianov began his career at the elite Preobrazhensky Regiment of the Imperial Guard (Russia) in 1772. In 1786 he was appointed Colonel of a Grenadier regiment and it was in this capacity that he began his distinguished career during the Russo-Turkish War (1787–92) under Catherine the Great. In the aforementioned war, he fought at Khotin, on the Salchea River, at Ismail, and Bender.[1]

In 1796 the Empress scrambled to belatedly punish Persia for its invasion of Georgia, sending-off Tsitsianov as part of the Persian Expedition of 1796 under the command of Count Valerian Zubov.[1] Following the mixed results of the mission, as well as the death of the Empress and the subsequent disorder associated with the reign of Emperor Paul I, Tsitsianov temporarily retired from service but returned to work after the enthronement of Alexander I.

Tsitsianov's rule in Georgia and wars in the Caucasus

In 1802 Tsitsianov was appointed the Governor General of newly annexed Eastern Georgia(Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti), where his rule was characterized by uncompromising policies towards the locals, including the exile of the remaining members of Georgia's formerly ruling dynasty to Russia.[7][8] He successfully carried out highly important projects, such as upgrading the Georgian Military Road, and by leading the Russian armies to successes in the early stages of the upcoming 1804-1813 Russo-Iranian war. Tsitsianov's name was commonly pronounced as "Sisianov" or "Zizianov" in Persian; however, his title, "the Inspector", was pronounced as "Ispokhdor" in Azeri Turkish.[8] Most Iranians referred to him by this title.[8] "Ispokhdor" literally translates as "his work is shit / he whose job is shit".[9][10] As Prof. Stephanie Cronin states, Tsitsianov presided over a new round of brutal military aggression, that triggered the Russo-Persian War of 1804-1813.[8] He had strong negative feelings towards Muslims in general and the "Persians" in particular, and held in contempt everything related to Iran.[8] A prime example of tactics and attitude were shown in the conquest of Ganja in early 1804.[8] As added by Cronin, Tsitsianov's conquest of Ganja, which reduced the city to rubble and resulted in the murder of its governor, Javad Khan, his son, and many of the city's defenders and civilian population, was no less brutal and murderous than Agha Mohammad Khan's sack of Tiflis in 1795.[8]

Though many resented his policies, Tsitsianov's rule brought some of the much needed stability for Georgians, particularly in terms of keeping at bay the previously rampant incursions and marauding by Lezgian mountaineers. When one of his generals was killed in battle with the Lezgians, his rage knew no bounds and wrote an angry letter to the Sultan of Elisu: "Shameless sultan with the soul of a Persian - so you still dare to write to me! Yours is the soul of a dog and the understanding of an ass, yet you think to deceive me with your specious phrases. Know that until you become a loyal vassal of my Emperor I shall only long to wash my boots in your blood":[11] Under the orders of Emperor Alexander I, he later led the Russian armies into the new Russo-Persian War. In the summer of 1804, he advanced against the Persian forces in Persian Armenia, and fought at Gyumri, Echmiadzin, on the Zang River, and finally Yerevan. His actions earned him the Order of St. Vladimir, 1st Degree.[1]

Death and related myths

In 1806 he rode up to the walls of Baku, with characteristic bravado, to partake in the ceremony of transferring the city to Russian rule after a successful siege. When the general was about to receive the keys to the city, troops loyal to the Khan of Baku unexpectedly shot him and his fellow Georgian aide-de-camp Elisbar Eristov, with Tsitsianov's head and both hands cut off. The third member of the small mission escaped to relate the gruesome tale.[12] His head was sent to Fat′h-Ali Shah Qajar in Tehran.

In relation to this episode, it is noteworthy that in 1806, Mirza Mohammad Akhbari, a teacher of Akhbari school of Fiqh (Islamic Law) in Tehran, allegedly promised Fat′h-Ali Shah Qajar to secure the death of Tsitsianov by supernatural means. Retreating for a period of forty days to the shrine at Shah-Abdol-Azim, he began to engage in certain magical practices, such as beheading wax figures representing Tsitsianov. After the general was in fact assassinated, his severed head (or, according to some accounts, hand) arrived in Tehran just before the forty days were up.[13] Because Fat′h-Ali Shah feared that the supernatural powers of Mirza might be turned against him, he exiled him to Arab Iraq.[14]

References

- Mikaberidze 2005, p. 406.

- Richmond, Walter (9 April 2013). The Circassian Genocide. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-6069-4.

- Gordin, Kavkaz. p. 73

- Potto, Valisii. Kavkazskaya voina. 1:171

- Rodovid: პავლე დიმიტრის ძე ციციანოვი დაბ. 1754 გარდ. თებერვალი 1806 Retrieved: June 28, 2013

- Mikaberidze 2015, p. 563.

- P. Longworth, Russia's Empires, John Murray, 2005, p.191.

- Cronin 2013, p. 55.

- Cronin 2013, p. 67.

- Tapper 1997, p. 152.

- Baddeley, Russian Conquest of the Caucasus, Chapter IV

- P. Longworth, Russia's Empires, John Murray, 2005, p.192.

- Algar, H. "AḴBĀRĪ, MĪRZĀ MOḤAMMAD". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 5 October 2011.

- Algar, Hamid (1969). Religion and State in Iran, 1785-1906: The Role of the Ulama in the Qajar Period. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press; 1st Edition (June 1980). pp. 64–66. ISBN 978-0-520-04100-4.

Sources

- Cronin, Stephanie (2013). Iranian-Russian Encounters: Empires and Revolutions Since 1800. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41562-433-6.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2005). Russian Officer Corps of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-1-61121-002-6.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2015). Historical Dictionary of Georgia (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-44224-146-6.

- Tapper, Richard (1997). Frontier Nomads of Iran: A Political and Social History of the Shahsevan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521583367.