Pauline Hopkins

Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins (1859 – August 13, 1930) was an American novelist, journalist, playwright, historian, and editor. She is considered a pioneer in her use of the romantic novel to explore social and racial themes, as demonstrated in her first major novel Contending Forces: A Romance Illustrative of Negro Life North and South. In addition, Hopkins is known for her significant contributions as Editor for the Colored American Magazine, which was recognized as being among the first periodicals specifically celebrating African-American culture through various short stories, essays and serial novels. She is also known to have prominent connections to other influential African-American figures of the time, such as Booker T. Washington and William Wells Brown.[1]

Pauline Hopkins | |

|---|---|

Hopkins circa 1901 | |

| Born | Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins 1859 Portland, Maine |

| Died | August 13, 1930 Cambridge, Massachusetts |

| Occupation | |

| Nationality | American |

| Genre | Romance novel |

| Notable works |

|

Hopkins' spent most of her life in Boston, Massachusetts, where she completed the majority of her life's work. As an active contributor to the racial, political and feminist discourse of the time, Hopkins is known as being one of the significant intellectuals of the early 20th century to contribute to racial uplift through her writing.[1]

Early life

Hopkins was born to Northrop Hopkins (also reported as Benjamin Northup) and Sarah A. Hopkins (née Allen) in Portland, Maine, and grew up in Boston, Massachusetts.[2] Her father was influential in Providence, Rhode Island, due to his political ties and her mother was a native of Exeter, New Hampshire. Her maternal ancestry traces back to the famous New-Hampshire natives Nathaniel and Thomas Paul, who were of religious prominence for their Baptist ministry and the latter for opening the first Black Baptist church in the Boston area.[1] Allegations of infidelity led to Allen filing for divorce and shortly afterwards she met and married William Hopkins.[3]

The high-achieving Hopkins household encouraged Pauline academically, which led her to develop an appreciation for literature. In addition to hailing from a well-educated household, she was inspired from an early age by the great African-American leaders of the time, such as Fredrick Douglass, whom she later cited as having "god-like gifts" in her recollection of attending one of his talks during adolescence.[4] In 1874, after completing her second year at Girls High School, she entered an essay contest held by the Congregational Publishing Society of Boston and funded by former slave, novelist, and dramatist William Wells Brown.[1] Her submission, "Evils of Intemperance and Their Remedy", highlighted the problems with intemperance and urged parents to be in control of their children's social upbringing. She placed first in the contest and won $10 in gold.[5]

She became well known for her various roles as a dramatist, actress and singer. In March 1877, she participated in her first dramatic performance, Pauline Western, the Belle of Saratoga. After this, she acted in several other plays and received positive reviews. However, it was not until the beginning of the 1900s that she decided to focus more on her literary passions.[6][7]

Literary career

Plays, novels and short stories

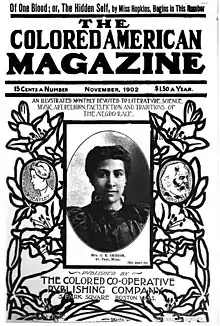

Her earliest known work, a musical play called Slaves’ Escape; or, The Underground Railroad (later revised as Peculiar Sam; or, The Underground Railroad), was first performed at Oakland Garden in Boston during the year 1880.[5] Afterwards, she wrote another unpublished play titled One Scene from the Drama of Early Days, which was dramatized rendition of the biblical story known as Daniel in the lions' den.[5] Her short story "Talma Gordon", published in 1900, is often noted as being the first African-American mystery story. She explored the difficulties faced by African-Americans amid the racist violence of post-Civil War America in her first novel, Contending Forces: A Romance Illustrative of Negro Life North and South, published in 1900. In the following years, she published three serial novels between 1901 and 1903 in the African-American periodical Colored American Magazine: Hagar's Daughter: A Story of Southern Caste Prejudice, Winona: A Tale of Negro Life in the South and Southwest, and Of One Blood: Or, The Hidden Self.

Of One Blood: Or, The Hidden Self

.jpg.webp)

The last of Hopkins' four novels, Of One Blood: Or, The Hidden Self, first appeared in serial form in The Colored American Magazine from November 1902 to November 1903, during the four-year period in which Hopkins served as its editor. Elements of the work have been compared to Goethe's Faust.[8]

Of One Blood: Or, The Hidden Self tells the story of Reuel Briggs, a medical student who does not care about being black or appreciating African history but finds himself in Ethiopia on an archaeological trip. His motive is to raid the country of lost treasures, which he does find. However, he discovers much more than he expected: the painful truth about blood, race, and the half of his history that was never told. Hopkins wrote the novel intending, in her own words, to "raise the stigma of degradation from [the Black] race." The title, Of One Blood, refers to the biological kinship of all human beings.

Although Of One Blood: Or, The Hidden Self is a work of fiction, Hopkins constructs an historical argument in her novel, using historical and literary sources, as well as travelogues.[9] Her argument, which ran counter to many histories of that time, was that the ancient cultures of the Nile Valley were African in origin, not imported to the area from elsewhere.

Colored American Magazine

From the beginning of the nine-year run of the Colored American Magazine, Hopkins served as a major contributor to the periodical's success. Hopkins short story "The Mystery Within Us" was included in the first issue of Colored American Magazine, a monthly periodical started by the same company who published Hopkins' novel Contending Forces in the same year. She was named Editor of the Women's Department by the second issue, and Literary Editor of the magazine by November 1903.[5] In addition, she would go on to write sketches for the periodical known as "Famous Women of the Negro Race" and "Famous Men of the Negro Race." This series gave recognition to many of the influential Black figures of the time through detailing their lives and legacies, including abolitionist William Wells Brown, the same inspiration who had awarded her for her essay-writing ability as a teenager nearly three decades earlier.

At times going by the pseudonym Sarah A. Allen, Hopkins' work at the Colored American began to gain recognition in the public eye. As a result of this, she was offered the opportunity to become a member of the board of directors, a shareholder and a creditor of the magazine. Along with her writing, she helped to increase subscriptions and raise funding for the magazine as a co-founder of "The American Colored League," which was an organization started in 1904 with the mission of promoting the interests of the Colored American[5]. These roles alone helped her break into the literary world, with her work making up a substantial amount of the literary and historical materials promoted by the magazine. She would continue to work for the magazine until she left in September 1804 due to health complications.[5] By her final issue, a total of six of Hopkins' short stories had been published in the magazine including the well-known mystery "Talma Gordon," as well as two of her novels Winona: A Tale of Negro Life in the South and Southwest and Of One Blood or The Hidden Self[5].

New Era Magazine

Hopkins' final notable works as a writer and editor occurred during the formation of the Boston-based New Era Magazine, which she created with Walter Wallace, whom she had previously worked with at the Colored American Magazine. The cover of the New Era Magazine included the subheading, "An Illustrated Monthly Devoted to the World-Wide Interests of the Colored Race." Despite its attempts to provide a space appealing to the literary and political interests of African-Americans in the context of the segregation era, the magazine only published two issues in 1916 before ceasing existence and receiving very little recognition within scholarly discourse at the time.[1] This is often regarded as a failure on Hopkins' part, marking the quiet conclusion of her literary career.

Reception

After presenting Contending Forces to the Women's Era Club of Boston, readings of the novel spread to other women's clubs throughout the country. It was hailed as being "...undoubtedly the book of the century.... absorbing from the first page to the last" by president of the Colored Women's Business Club of Chicago, Alberta Moore Smith.[5]

Despite the significant contributions through her life's work, Hopkins received very little public recognition in comparison to many of her male counterparts. Her name would be largely forgotten during the time of the Harlem Renaissance, during which other African American artists received much recognition, leading up to her death.[1] Many details of her life would fall into obscurity until scholar Ann Allen Shockley's biographical essay "Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins: A Biographical Excursion into Obscurity" in 1972, which was followed by her work being featured in The Schomburg Library of Nineteenth-Century Black Women Writers during 1988.[1]

Legacy

Hopkins is remembered for writing the first, if not one of the first mystery drama plays by a Black woman. She is has also been recognized as "...the most prolific contributor to the Colored American Magazine" during the four years that regularly contributed to the periodical, setting the foundation for what the magazine would become even after her eventual departure.[10] Her various works for the magazine such as "Famous Women of the Negro Race" (1901-1902) were known to combat the stereotypes enforced on African-American Americans through showcasing the great successes of the race, often shedding light on the experiences of women in particular.[10]

In 1988, Oxford University Press released The Schomburg Library of Nineteenth-Century Black Women Writers with Professor Henry Louis Gates as the general editor of the series. Hopkins' novel Contending Forces: A Romance Illustrative of Negro Life North and South (with an introduction by Richard Yarborough) was reprinted as a part of this series. Her magazine novels (with an introduction by Hazel Carby) were also reprinted as a part of this series. Carby did this as a way to reintroduce Hopkins into the sphere and see how her literature influenced writers in the past, present and now future.

Her work has been regarded among other notable African-American writers at the time such as Charles Chesnutt, Paul Laurence Dunbar, and Sutton Griggs by Richard Yarborough. In relation to women's publications, Yarborough calls her "the single most productive black woman writer at the turn of the century."[11]

"The Northup legacy that Pauline Hopkins would claim as her own was one of impressive public action, fearless civic ambition and strong community consciousness."[3]

Death

In the years leading up to her death, Hopkins was actively employed as a stenographer for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.[5] On August 12, 1930, she died from injuries sustained after an accident, during which bandages that she was wearing on her arms to treat her neuritis, soaked in liniment, caught aflame from an oil stove that she had in her room. She died in Cambridge, Massachusetts and was buried in the Garden Cemetery in Chelsea, Massachusetts.[5] Despite the fact that she had resided in the area during the course of most of her life's work, there was no record of her death posted in the local obituaries. Both The Chicago Defender and the Baltimore-Afro-American newspapers reported on her death, wrongly citing her age of death as 79. The Cambridge Death Records of the Massachusetts Department of Vital Statistics confirm that her actual age of death was 71.[5] To this day, many details of her life are still undiscovered, including her exact birthdate.

Published works

- Slaves’ Escape; or, The Underground Railroad, 1880.

- Contending Forces: A Romance Illustrative of Negro Life North and South Archived 2016-10-10 at the Wayback Machine, 1900.

- "Talma Gordon". First published in The Colored American Magazine, 1900.

- Hagar's Daughter: A Story of Southern Caste Prejudice. First published serially in The Colored American Magazine, 1901–02.

- Winona: A Tale of Negro Life in the South and Southwest. First published serially in The Colored American Magazine, 1902–03.

- Of One Blood: Or, The Hidden Self. First published serially in The Colored American Magazine, 1903.

- Of One Blood: Or, the Hidden Self. Edited by Deborah McDowell. Washington Square Press, 2004.

- Of One Blood: Or, the Hidden Self. Edited by Eurie Dahn and Brian Sweeney. Broadview Press, 2022.

- Of One Blood was rereleased by the MIT Press as part of the Radium Age Series in 2022. This edition featured an introduction by Minister Faust.

See also

- The Music Trades, "History," "Post-1996 findings on Freund" (relating to Colored American Magazine)

References

- Wallinger, Hanna (2005). Pauline E. Hopkins: A Literary Biography. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-2704-4.

- "Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins (1859-1930) •". 22 November 2011.

- Brown, Lois (2008). Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins: Black Daughter of the Revolution. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807831663.

- Hopkins, Pauline (1900). "Hon. Frederick Douglass". Colored American Magazine. Famous Men of the Negro Race. 2 (2): 121–132.

- Shockley, Ann Allen (1927). "Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins: A Biographical Excursion into Obscurity". Phylon. 33 (1): 22–26. doi:10.2307/273429. JSTOR 273429.

- Shockley, Ann Allen (1927). "Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins: A Biographical Excursion into Obscurity". Phylon. 33 (1): 23–24. doi:10.2307/273429. JSTOR 273429.

- Hodder, Kevin (November 22, 2011). "Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins (1859–1930)". BlackPast.org. Retrieved January 31, 2022.

- "‘Into the high ancestral spaces’: Pauline Hopkins` Of One Blood and Goethe's Faust", Sabine Isabell Engwer, Free University of Berlin, John F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies.

- Davies, Vanessa (2021). "Pauline Hopkins' Literary Egyptology". Journal of Egyptian History. 14 (2): 127–144. doi:10.1163/18741665-bja10006. S2CID 245415904. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- "Index". The Digital Colored American Magazine. 2017-02-18. Retrieved 2022-12-06.

- Gruesser, John Cullen (1996). The Unruly Voice: Rediscovering Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252065545.

Further reading

- Allen, Carol (1998), Black Women Intellectuals: Strategies of Nation, Family, and Neighborhood in the Works of Pauline Hopkins, Jessie Fauset, and Marita Bonner, New York, NY: Garland, ISBN 9780815331124.

- Anderson, Cordell Sigrid (2006), "'The Case Was Very Black against' Her: Pauline Hopkins and the Politics of Racial Ambiguity at the Colored American Magazine", American Periodicals, 16 (1): 52–73, doi:10.1353/amp.2006.0003, JSTOR 20770946, S2CID 145290964.

- Brown, Lois (2008), Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins: Black Daughter of the Revolution, Chapel Hill, NC: U of North Carolina P, ISBN 9781469614564.

- Campbell, Jane (1986), Mythic Black Fiction: The Transformation of History, Knoxville, TN: U of Tennessee P, ISBN 9780870495939.

- Carby, Hazel (1987), Reconstructing Womanhood: The Emergence of the Afro-American Woman Novelist, New York, NY: Oxford UP, ISBN 9780195060713.

- Davies, Vanessa (2021). "Pauline Hopkins' Literary Egyptology". Journal of Egyptian History. 14 (2): 127–144. doi:10.1163/18741665-bja10006. S2CID 245415904. Retrieved 10 February 2022..

- Dworkin, Ira, ed. (2007), Daughter of the Revolution: The Major Nonfiction Works of Pauline E. Hopkins, Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers UP, ISBN 9781469614564.

- Gabler-Hover, Janet (2000), Dreaming Black, Writing White: The Hagar Myth in American Cultural History, Lexington, KY: UP of Kentucky, ISBN 9780813121437.

- Gruesser, John C, ed. (1996), The Unruly Voice: Rediscovering Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins, Urbana, IL: U of Illinois P, ISBN 9780252022302.

- Knight, Alisha R (2012), Pauline Hopkins and the American Dream: An African American Writer's (Re)Visionary Gospel of Success, Knoxville, TN: U of Tennessee P, ISBN 9781572339545.

- Reuben, Paul P, "Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins", PAL: Perspectives in American Literature: A Research and Reference Guide.

- Shockley, Ann Allen (1972), "Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins: A Biographical Excursion into Obscurity", Phylon, 33 (1): 22–26, doi:10.2307/273429, JSTOR 273429.

- Shockley, Ann A (1988), Afro-American Women Writers, 1746-1933: An Anthology and Critical Guide, Boston, MA: G.K. Hall, ISBN 9780452009813.

- Wallinger, Hanna (2005), Pauline E. Hopkins: A Literary Biography, Athens, GA: U of Georgia P, ISBN 9780820343457.

External links

| Library resources about Pauline Hopkins |

| By Pauline Hopkins |

|---|

- "Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins", Voices from the Gaps, University of Minnesota

- Hopkins profile at Literary Encyclopedia

- Perspectives in American Literature - Pauline Hopkins bibliography Archived 2012-08-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Martin Japtok's critical essay, "Pauline Hopkins's Of One Blood, Africa, and the 'Darwinist Trap'"

- Home page for The Schomburg Library of Nineteenth-Century Black Women Writers

- The Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins Society

- Reuben, Paul P. "Chapter 6: Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins." PAL: Perspectives in American Literature - A Research and Reference Guide - An Ongoing Project Archived 2012-08-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Works by or about Pauline Hopkins at Internet Archive

- Works by Pauline Hopkins at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Pauline Hopkins at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)