Great Peace of Montreal

The Great Peace of Montreal (French: La Grande paix de Montréal) was a peace treaty between New France and 39 First Nations of North America that ended the Beaver Wars. It was signed on August 4, 1701, by Louis-Hector de Callière, governor of New France, and 1300 representatives of 39 Indigenous nations.[1]

| La Grande paix de Montréal | |

|---|---|

Copy of the treaty including signatures | |

| Signed | August 4, 1701 |

| Location | Montreal, New France |

| Signatories | |

| Languages |

|

The French, allied to the Hurons and the Algonquins, provided 16 years of peaceful relations and trade before war started again. Present for the diplomatic event were the various peoples; part of the Iroquois confederacy, the Huron peoples, and the Algonquin peoples.[2]

This has sometimes been called the Grand Settlement of 1701,[3] not to be confused with the unrelated Act of Settlement 1701 in England. It has often been referred to as La Paix des Braves, meaning "The Peace of the Braves".

The Fur Wars

The foundation of Quebec City in 1608 by Samuel de Champlain, one of the first governors of New France, marked the beginning of the gathering of resources of the Great Northern forests by traders from Metropolitan France. Control over the fur trade became a high-stakes game among the Native American tribes, as all of them wanted to be the European's chosen intermediary. The "Fur-Wars" saw the Hurons and Algonquins, supported by the French, pitted against the Iroquois of the powerful League of Five Nations, who were supported first by New Netherlands, and later by the English when they took New Amsterdam in the 1660s and 1670s, renaming it New York City.

In the first half of the 17th century, the Dutch-allied Iroquois made substantial territorial gains against the French-allied First Nations, often threatening French settlements at Montreal and Trois-Rivières. In an attempt to secure the colony, in 1665 the Carignan-Salières Regiment was sent to New France. Their campaign in 1666 devastated a number of Mohawk communities, who were forced to negotiate a peace. A period of prosperity followed for France's colony, but the Iroquois, now supported by the English, continued to expand their territory westward, fighting French allies in the Great Lakes region and again threatening the French fur trade. In the 1680s the French became actively involved in the conflict again, and they and their allied Indians made significant gains against the Iroquois, including incursions deep into the heartland of Iroquoia (present-day Upstate New York). After a devastating raid by the Iroquois against the settlement of Lachine in 1689, and the entry the same year of England into the Nine Years' War (known in the English colonies as King William's War), Governor Frontenac organized raiding expeditions against English communities all along the frontier with New France. French and English colonists, and their Indian allies, then engaged in a protracted border war that was formally ended when the Treaty of Ryswick was signed in 1697. The treaty, however, left unresolved the issue of Iroquois sovereignty (both France and England claimed them as part of their empire), and French allies in the upper Great Lakes continued to make war on the Iroquois.

Prelude to peace

The success of these attacks, which again reached deep into Iroquois territory, and the inability of the English to protect them from attacks originating to their north and west, forced the Iroquois to more seriously pursue peace. Their demographic decline, aided by conflicts and epidemics, put their very existence into doubt. At the same time, commerce became almost nonexistent because of a fall in the price of furs. The Indians preferred to trade with the merchants of New York because these merchants offered better prices than the French.

Preliminary negotiations took place in 1698 and 1699, but these were to some degree frustrated by the intervention of the English, who sought to keep the Iroquois from negotiating directly with the French. After another successful attack into Iroquoia in early 1700, these attempts at intervention failed. The first conference between the French and Iroquois was held on Iroquois territory at Onondaga in March 1700. In September of the same year, a preliminary peace treaty was signed in Montreal with the five Iroquois nations. Thirteen First Nations symbols are on the treaty. After this first entente, it was decided that a bigger one would be held in Montreal in the summer of 1701 and all Nations of the Great Lakes were invited. Selected French emissaries, clergies and soldiers, all well-perceived by the First Nations, were given this diplomatic task. The negotiations continued during the wait for the big conference; the neutrality of the Five Nations was discussed in Montreal in May 1701. The treaty of La Grande Paix de Montreal of July 21 to August 7 of 1701[4] was signed as a symbol of peace between the French and the First Nations. In the treaty, the Five Nations agreed to remain peaceful between the French and the British during times of war together. It was a huge example of peace between different nations and honouring an agreement.

Treaty ratification

The first delegations arrived in Montreal at the beginning of the summer of 1701, often after long, hard journeys. The ratification of the treaty was not agreed to immediately due to the discussions between the First Nations representatives and Governor Callière's dragging on, both sides being eager to negotiate as much as possible. The actual signing of the document took place on a big field prepared for the special occasion, just outside the city. The representatives of each Nation placed their clan's symbol, such as turtle, wolf or bear, at the bottom of the document. A great banquet followed the solemn occasion, with a peace pipe being shared by the chiefs, each of them praising peace in turn. This treaty, achieved through negotiations according to First Nations diplomatic custom, was meant to end ethnic conflicts. From then on, negotiation would trump direct conflict and the French would agree to act as arbiters during conflicts between signatory tribes. The Iroquois promised to be neutral in case of conflict between the French and English colonies.

Aftermath

The treaty was highly symbolic for the aboriginal nations as the Tree of Peace was now established among all the Great Lakes' nations. Commerce and exploratory expeditions quietly resumed in peace after the signing of the treaty. The French explorer Antoine Laumet de La Mothe, Sieur de Cadillac left Montreal to explore the Great Lakes region, founding Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit (now Detroit) in July. Jesuit priests resumed their spiritual mission-based work in the north. The Great Peace of Montreal is a unique diplomatic event in the history of both North and South America. The treaty is still considered valid by the Indigenous people of the American First Nations tribes involved.

The French in negotiating followed their traditional policy in North and South America, where their relationship with some of the natives was characterized by mutual respect and admiration and based on dialogue and negotiation. According to the 19th-century historian Francis Parkman: "Spanish civilization crushed the Indian; English civilization scorned and neglected him; French civilization embraced and cherished him."[5]

Attendees and signatories

- Haudenosaunee

- Onondaga, Seneca, Oneida and Cayuga, represented by Seneca orators (Tekanoet, Aouenan, and Tonatakout) and by Ohonsiowanne (Onondaga), Toarenguenion (Oneida), Garonhiaron (Cayuga), and Soueouon (Oneida), who were signatories.

- Mohawk, Teganiassorens

- Sault St. Louis (Kahnawake) Mohawk, represented by L'Aigle (The Eagle)

- Iroquois of La Montagne, represented by Tsahouanhos[6]

- Amikwa (Beaver People), represented by Mahingan, and spoken for by the Odawas in the debates

- Cree, or at least one Cree band from the area northwest of Lake Superior

- Meskwaki (the Foxes or Outagamis), represented by Noro & Miskouensa

- Les Gens des terres (Inlanders), possibly a Cree-related group

- Petun (Tionontati), represented by Kondiaronk, Houatsaranti and Quarante Sols (Huron of the St. Joseph)

- Illinois Confederation, represented by Onanguice (Potawatomi) and possibly by Courtemanche

- Kickapoo (attendance is disputed by Kondiaronk)[6]

- Mascouten, represented by Kiskatapi

- Menominee (Folles Avoines), represented by Paintage

- Miami people, represented by Chichicatalo

- Miamis of the St. Joseph River (Sakiwäsipi)

- Piankeshaw

- Wea (Ouiatenon),

- Mississaugas, represented on August 4 by Onanguice (Potawatomi)

- Nippissing, represented by Onaganioitak

- Odawa

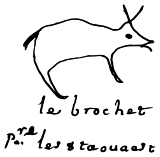

- Sable Odawas (Akonapi), represented by Outouagan (Jean Le Blanc) and Kinonge (Le Brochet)

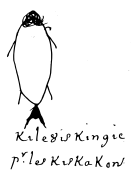

- Kiskakons (Culs Coupez), represented by Hassaki (speaker) and Kileouiskingie (signatory)

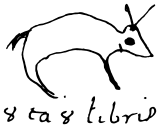

- Sinago Odawas, represented by Chingouessi (speaker) and Outaliboi (signatory)

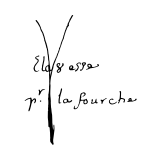

- Nassawaketons (Odawas of the Fork), represented by Elaouesse

- Ojibwe (Saulteurs), represented by Ouabangue

- Potawatomi, represented by Onanguice and Ouenemek

- Sauk, represented by Coluby (and occasionally by Onanguice)

- Timiskamings from Lake Timiskaming

- Ho-Chunk (Otchagras, Winnebago, Puants)

- Algonquins

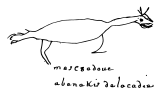

- Abenaki, represented by Haouatchouath and Meskouadoue, likely speaking for the entire Wabanaki Confederacy[6]

See "Nindoodemag": The Significance of Algonquian Kinship Networks in the Eastern Great Lakes Region, 1600-1701 (pp. 23–52) by Heidi Bohaker for a discussion of the significance of these pictographical signatures.

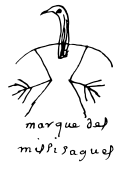

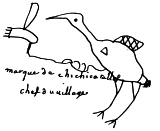

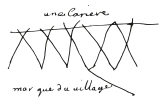

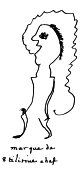

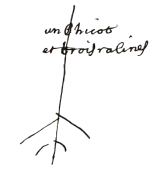

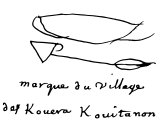

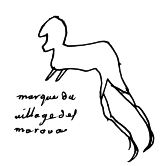

- Marks and Signatures on the Great Peace of Montreal

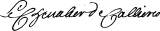

Louis-Hector de Callière signed for France.

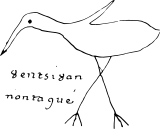

Louis-Hector de Callière signed for France. Mark: Wader.

Mark: Wader.

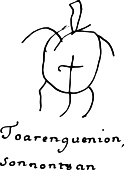

Ouentsiouan signed for Onondagas. Mark: Turtle.

Mark: Turtle.

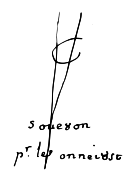

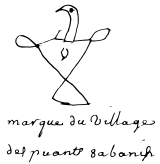

Tourengouenon signed for Senecas. Mark: A standing stone between a fork.

Mark: A standing stone between a fork.

Signed for Oneidas.

Mark: Bear.

Mark: Bear.

Kinongé signed for Sable Odawas. Mark: Bear.

Mark: Bear.

Outaliboi signed for Sinagos Odawas. Mark: Fish.

Mark: Fish.

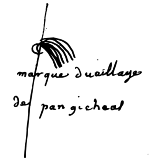

Kileouiskingié signed for Kiskakons. Mark: A fork.

Mark: A fork.

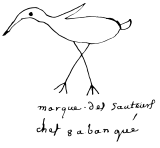

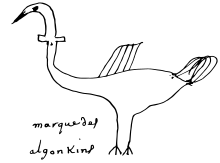

Elaouesse signed for Nassawaketons (Odawas of the Fork).

Mark: Crane.

Mark: Crane.

Ouabangue signed for Ojibwe. Mark: Beaver.

Mark: Beaver.

Mahingan signed for Amikwa..svg.png.webp) Mark: Sturgeon.

Mark: Sturgeon.

Coluby signed for Sauk. Mark: Fox.

Mark: Fox.

Signed for Meskwaki.

.svg.png.webp)

Mark: Crane.

Mark: Crane.

Chichicatalo signed for Miami.

Mark: Chief.

Mark: Chief.

Outilirine possibly signed for Cree. Mark: Tree and roots.

Mark: Tree and roots.

Signed for Potawatomi.

Mark: Turtle.

Mark: Turtle.

Signed for Peoria. Mark: Unknown.

Mark: Unknown.

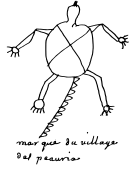

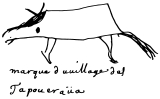

Signed for Tapouara. Mark: Unknown.

Mark: Unknown.

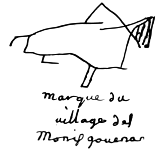

Signed for Moingona. Mark: Frog.

Mark: Frog.

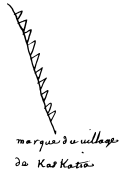

Signed for Maroa. Mark: Notched feather.

Mark: Notched feather.

Signed for Kaskaskia.

Mark: Crane.

Mark: Crane.

Signed for Algonkin. Mark: Deer.

Mark: Deer.

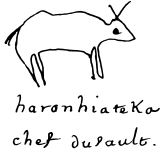

Haronhiateka signed for Sault (Kahnawake) Mark: Deer.

Mark: Deer.

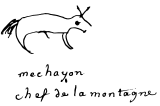

Mechayon signed for the People of the Mountain (Iroquois of La Montagne)

Commemoration

A square in Old Montreal was renamed Place de la Grande-Paix-de-Montréal to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the peace. Several locations in Quebec are named for the Petun leader Kondiaronk, one of the architects of the peace, including the Kondiaronk Belvedere in Mount Royal Park overlooking downtown Montreal.

Notes

- Francis, Daniel. Voices and Visions. Oxford University Press. p. 82.

- Charlotte Gray The Museum Called Canada: 25 Rooms of Wonder Random House, 2004

- "Grand Settlement of 1701". Archived from the original on 2009-09-28. Retrieved 2013-09-17.

- Gilles, Havard (2001). Great Peace of Montreal of 1701 : French-Native Diplomacy in the Seventeenth Century. Montreal, Canada: McGill-Queens University Press. pp. 143–144. ISBN 0-7735-2219-0.

- Quoted in Cave, p.42

- Havard, Gilles; Aronoff, Phyllis; Scott, Howard (2001). The Great Peace of Montreal of 1701: French-native Diplomacy in the Seventeenth Century. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. pp. 119–121. ISBN 9780773522190. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

References

- Alfred A. Cave The French and Indian War 2004 Greenwood Press ISBN 0-313-32168-X

- Atherton, William. Montreal, 1535–1914

- Eccles, W. J. Biography of Denonville at DCB