Treaty of Breda (1667)

The Peace of Breda, or Treaty of Breda was signed in the Dutch city of Breda, on 31 July 1667. It consisted of three separate treaties between England and each of its opponents in the Second Anglo-Dutch War: the Dutch Republic, France, and Denmark–Norway. It also included a separate Anglo-Dutch commercial agreement.

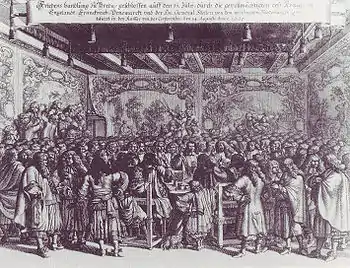

Contemporary engraving of the signing of the peace at Breda Castle | |

| Context | England, the Dutch Republic, France and Denmark–Norway end the Second Anglo-Dutch War |

|---|---|

| Signed | 31 July 1667 |

| Location | Breda |

| Effective | 24 August 1667 |

| Mediators | |

| Negotiators | |

| Signatories | |

| Parties | |

Negotiations had been in progress since late 1666 but were slow, as both sides tried to improve their positions. This changed after the French invasion of the Spanish Netherlands in late May, which the Dutch viewed as a more serious threat. War-weariness in England was increased by the June Raid on the Medway. Both factors led to a rapid agreement of terms.

Prior to 1667, the Anglo-Dutch relationship had been dominated by commercial conflict, which the treaty did not end entirely. However, tensions decreased markedly and cleared the way for the 1668 Triple Alliance between the Dutch Republic, England and Sweden. With the brief anomaly of the 1672 to 1674 Third Anglo-Dutch War, the treaty marked the beginning of an alliance between the English and the Dutch that would last for a century.

Background

The Second Anglo-Dutch War was caused by commercial tensions, heightened by Charles II, who saw trade as a way to reduce his financial dependence on Parliament. In 1660, he and his brother James founded the Royal African Company (RAC), challenging the Dutch in West Africa. Investors included senior politicians such as George Carteret, Shaftesbury and Arlington, creating a strong link between the RAC and government policy.[2]

Huge profits from Asian spices led to conflict even in times of peace, as the Dutch East India Company, or VOC, first created, then enforced, their monopoly over production and trade. By 1663, indigenous and European competitors like the Portuguese had been eliminated, leaving only nutmeg plantations on Run.[3] These had been established by the British East India Company in 1616, before being evicted by the VOC in 1620; when the English re-occupied Run in late 1664, the Dutch expelled them again, this time destroying the plantations.[4]

There was a similar struggle over the Atlantic trade between the Dutch West-Indische Compagnie, or WIC, and competitors from Spain, Denmark, Sweden, Portugal and England.[5] Sugar plantations in the Americas were cultivated by slaves from Africa, fed by colonies in North America, leading to conflict in all three regions. In August 1664, the English occupied New Netherland, later renamed New York; when another attack captured WIC slave trade posts in modern Ghana, the Dutch sent a fleet to recapture them.[6] The result was to bankrupt the RAC, whose investors saw war as the best way to recoup their losses.[7]

Despite the Franco-Dutch treaty of April 1662, Louis XIV initially remained neutral, as French and Dutch economic interests increasingly diverged over the Spanish Netherlands. The 1648 Peace of Münster permanently closed the Scheldt estuary and the port of Antwerp, which did not recover economically until the 19th century. The combination gave Amsterdam effective control of trade in North-West Europe.[8] Louis considered the Spanish Netherlands his by right of marriage to Maria Theresa of Spain but hoped to acquire them peacefully. Negotiations with the Dutch continually broke down over his desire to re-open Antwerp as an export route for French goods. By 1663, he concluded they would never make concessions voluntarily and began planning a military intervention.[9]

In early 1665, England signed an alliance with Sweden against the Dutch, who suffered a serious defeat at Lowestoft in June, followed by an invasion from Münster.[10] Louis responded by activating the 1662 treaty, calculating this would make it harder for the Dutch to oppose his occupation of the Spanish Netherlands.[11] He also paid Sweden to remain neutral, while influencing Denmark–Norway to join the war. Danish assistance saved the Dutch merchant fleet at the Battle of Vågen in August, although this turned out to have been the result of miscommunication. Frederick III of Denmark had secretly agreed to help the English capture the fleet in return for a share of the profits, but his instructions arrived too late.[12]

By late 1666, Charles was short of money, largely due to his refusal to recall Parliament, while English trade had been badly affected by the war and domestic disasters. In contrast, the Dutch economy had largely recovered from its post-1665 contraction, while public debt was lower in 1667 than 1652; however, naval warfare was enormously expensive and financing it a challenge even for the Amsterdam markets.[13] Both sides wanted peace, since the Dutch had little to gain from continuing the war and faced external challenges from competitors. Denmark resented concessions imposed at Christianopel in 1647, while the WIC's confiscation of Danish ships was an ongoing source of dispute; in early 1667, they joined Sweden and France in imposing tariffs on Dutch goods, impacting the Baltic grain trade.[14]

In October 1666, Charles opened discussions with the States-General of the Netherlands, under the pretext of arrangements to return the body of Vice-Admiral William Berkeley, killed in the Four Days' Battle. He invited the Dutch to negotiations in London and withdrew previous demands for the appointment of his nephew William of Orange as stadtholder, payment of damages, the return of Run and a trade deal on India. The States-General refused to attend peace talks without France; on territorial claims, they offered to continue the present situation, or revert to the position before the war, an option clearly unacceptable to the English.[15]

It is questionable how sincere this offer from Charles actually was, since his envoy in Paris, the Earl of St Albans, was simultaneously holding secret talks on an Anglo-French alliance. Louis agreed to ensure the Dutch complied with English demands, in exchange for a free hand in the Spanish Netherlands; by April 1667, diplomats in The Hague were predicting a deal was imminent. When talks eventually began, the English delegation felt their position was extremely strong.[16]

Negotiations

Grand Pensionary Johan de Witt and the States of Holland rejected English proposals to negotiate in The Hague, a town dominated by the Orangist opposition. They were supported by Louis, who viewed the Orangists as English agents.[17] Angered by the delay, the States of Zeeland, Gelderland, Groningen, Overijssel and Friesland threatened to stop paying for a war 'continued only by Holland's obstinacy.'[18]

The parties eventually settled on Breda, but French military preparations led the Orangists to accuse De Witt of deliberately stalling to allow Louis a free hand in the Spanish Netherlands.[19] This put De Witt under pressure to reach agreement, which increased after France and Portugal agreed an anti-Spanish alliance in March.[20]

The role of mediator in peace talks provided prestige and the opportunity to build relationships; since Louis and Leopold both wanted the position, they compromised by using Swedish diplomats.[21] Key players in the vital Baltic trade in grain, iron and shipping supplies, the Swedes hoped to remove commercial concessions imposed by the Republic in the 1656 Treaty of Elbing and end its alliance with Denmark.[22] Göran Fleming was based at Breda, with Peter Coyet in The Hague; after Coyet died on 8 June, he was replaced by Count Dohna, who was instructed to negotiate a Swedish-English-French alliance if talks at Breda failed.[23]

The States General appointed eight delegates but only those from Holland, Zeeland and Friesland were actually present. Two of the three were Orangists, Zeelandic Pensionary Pieter de Huybert and Friesland's van Jongestall; the delegate from Holland, Van Beverningh, was a member of De Witt's States Party.[24] The English lead negotiators were Denzil Holles, Ambassador to France, and Henry Coventry, Ambassador to Sweden.

On 24 May, Louis launched the War of Devolution, French troops quickly occupying much of the Spanish Netherlands and Franche-Comté.[9] To focus on this, Spain needed to end the long-running Portuguese Restoration War. On 27 May, the Anglo-Spanish Treaty of Madrid formally concluded the 1654 to 1660 war and in return for commercial concessions, England agreed to mediate with Portugal.[25]

The threat to the Dutch economy presented by French expansion made ending the Anglo-Dutch War a matter of urgency. Backed by assurances from Louis that he would force the Dutch to agree concessions, the English increased their demands and Van Beverningh told De Witt a major military victory was needed to improve their bargaining position.[26] An opportunity was provided by Charles, who decommissioned most of the Royal Navy in late 1666 as a cost-saving measure. The Dutch took full advantage in the June 1667 Medway Raid; although the action itself had limited strategic impact, it was a humiliation Charles never forgot.[27]

Holles and Coventry initially assumed this would extend negotiations, but the need to create an alliance against France meant Spain threatened to withhold implementation of the Madrid treaty, supported by Leopold. Combined with economic losses caused by the war and the Great Fire of London, Clarendon instructed Holles to agree terms "to calm people's minds" and "free the king from a burden...he is finding hard to bear".[28]

Terms

Article 1 of the treaty stipulated a limited military alliance, obliging fleets or single ships sailing on the same course to defend each other against a third party.[29] Article 3 established the principle of uti possidetis, or "what you have, you hold", with an effective date of 20 May. The Dutch kept Surinam, now part of modern Suriname, Fort Cormantin and Run while the English kept New Netherland, which was subsequently divided into the colonies of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Connecticut and Delaware.[30]

Articles 4 to 8 applied the same principle to losses of goods or ships, including those that occurred before the war. No indemnities could be levied or punishments imposed, but all existing Letters of Marque were declared void.[31] To allow time to communicate these instructions, Article 7 varied the date on which they would be enforced: 5 September for the English Channel and the North Sea, 5 October for the other European seas, 2 November for the African coast north of the Equator and 24 April 1668 for the rest of the world.[29]

Article 10 required all prisoners to be exchanged without ransom although the Dutch later demanded reimbursement of their living expenses, which the English viewed as the same thing.[32] After their failed 1666 coup, many Orangists sought refuge in England, with English and Scots dissidents going the other way. In Articles 13 and 17, both sides undertook not to protect each other's rebels; in a secret annex, the Dutch undertook to extradite regicides who voted for the Execution of Charles I in 1649, although in practice these provisions were ignored.[29]

A separate treaty amended the Navigation Acts; goods transported along the Rhine or Scheldt to Amsterdam could be carried by Dutch ships to England without being subject to tariffs. England also accepted the principle of "free ships make free goods", which prevented the Royal Navy from intercepting Dutch ships during wars in which the Dutch were neutral.[33] These terms were preliminary, with a definitive text signed on 17 February 1668.[29]

The Danish and French treaties followed the Anglo-Dutch version in waiving claims for restitution of losses. In addition, England returned the French possessions of Cayenne and Acadia, captured in 1667 and 1654 respectively, but the exact boundaries were not specified, and the handover was delayed until 1670. England regained Montserrat and Antigua, with the Caribbean island of Saint Kitts divided between both countries.[34] After the treaties were signed on 31 July, they were sent to each country for ratification, a process which was completed by 24 August and followed by public celebrations in Breda.[35]

Aftermath

_van_het_Amsterdamse_lakenbereidersgilde_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

By exchanging New Netherland and Run, Breda removed two major areas of dispute, reducing Anglo-Dutch tensions overall and clearing the way for the 1668 Triple Alliance between the Republic, Sweden and England.[36] The Alliance is often credited with forcing France to return most of their gains at Aix-la-Chapelle, whereas the terms had already been agreed by Louis and Leopold in January 1668.[37] In the longer term, Breda was the point when the English and Dutch came to view France as a greater threat than each other; although Charles' preference for a French alliance led to the 1670 Secret Treaty of Dover, the long-term trend was against him.[38] Support for re-asserting English naval power provided limited backing in the Third Anglo-Dutch War but ended once that had been achieved.[39]

The treaty disappointed Orangists by failing to restore the House of Orange or allow exiles home, as promised by Charles. When Zeeland and Friesland, in response to the French advance, proposed William be made Captain-General of the Dutch States Army, the States of Holland responded on 5 August with the Perpetual Edict. This abolished the position of Stadholder of Holland, while a second resolution agreed to oppose that any confederate Captain-General or Admiral-General would become stadtholder of another province.[40] Since the army was viewed as an Orangist power base, spending on it was deliberately minimised; this had catastrophic effects in 1672.[41]

Breda was also a success for Sweden, who used their position as mediators to improve the Elbing provisions, break the Dutch-Danish agreement and join the Triple Alliance. The Spanish regained Franche-Comté and most of the Spanish Netherlands; more significantly, the Dutch now viewed them as a better neighbour than an ambitious France.[42] Overall, the Dutch considered Breda and the creation of the Alliance a diplomatic triumph; the period immediately following is often considered the high point of the Dutch Golden Age.[43]

References

- Davenport & Paullin 1929, p. 120.

- Sherman 1976, pp. 331–332.

- Le Couteur & Burreson 2003, pp. 30–31.

- Le Couteur & Burreson 2003, p. 32.

- Rommelse 2006, p. 91.

- Rommelse 2006, p. 112.

- Rommelse 2006, p. 196.

- Israel 1989, pp. 197–99.

- Geyl 1936, p. 311.

- Rommelse 2006, p. 168.

- De Périni 1896, p. 298.

- Kelsall 2008, pp. 206–07.

- Veenendaal 1994, p. 124.

- Kelsall 2008, p. 223.

- Geyl 1939, pp. 257–58.

- Pincus 1996, pp. 389–90.

- Grever 1982, p. 237.

- Grever 1982, p. 241.

- Grever 1982, p. 243.

- Gooskens 2016, p. 69.

- Gooskens 2016, pp. 65–66.

- Gooskens 2016, pp. 57–58.

- Gooskens 2016, p. 70.

- Grever 1982, pp. 245–46.

- Newitt 2004, p. 228.

- Blok 1925, p. 153.

- Boniface 2017.

- Geyl 1939, p. 266.

- Lesaffer 2016, pp. 124–138.

- Farnham 1901, pp. 311, 314.

- Davenport & Paullin 1929, pp. 129–130.

- Pepys 1667.

- Israel 1997, pp. 316–317.

- Davenport & Paullin 1929, pp. 138–140.

- Gooskens 2016, p. 71.

- Boxer 1969, p. 70.

- Davenport & Paullin 1929, pp. 144, 152.

- Lee 1961, p. 62.

- Rommelse 2006, pp. 198–201.

- Geyl 1939, pp. 269–70.

- Geyl 1936, pp. 312–13.

- Lynn 1996, p. 108.

- Swart 1969, pp. 1–24.

Sources

- Blok, P.J. (1925). Geschiedenis van het Nederlandsche volk. Deel 3. Sijthoff.

- Boniface, Patrick (14 June 2017). "The Royal Navy's Darkest Day: Medway 1667". Military History. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Boxer, C. R. (1969). "Some Second Thoughts on the Third Anglo-Dutch War, 1672–1674". Trans. R. Hist. Soc. 19: 67–94. doi:10.2307/3678740. JSTOR 3678740. S2CID 159934682.

- Britannica.com. "Treaty of Breda". Britannica.com. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- Davenport, Frances; Paullin, Charles (1929). European treaties bearing on the history of the United States and its dependencies: Volume II. Carnegie Institution.

- De Périni, Hardÿ (1896). Batailles françaises, 1660–1700 V4. Ernest Flammarion, Paris.

- Farnham, Mary Frances (1901). Documentary History of the State of Maine, Vol. 7: Containing the Farnham Papers; 1603 1688 (2019 ed.). Forgotten Books. ISBN 978-1528484718.

- Geyl, P (1936). "Johan de Witt, Grand Pensionary of Holland, 1653–72". History. 20 (80): 303–319. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1936.tb00103.x. JSTOR 24401084.

- Geyl, Pieter (1939). Orange & Stuart 1641-1672 (1969 ed.). Oosthoek's. ISBN 1842122266.

- Gooskens, Frans (2016). Sweden and the Treaty of Breda in 1667 – Swedish diplomats help to end naval warfare between the Dutch Republic and England (PDF). De Oranje-boom; Historical and Archeology Circle of the City and Country of Breda.

- Grever, John (1982). "Louis XIV and the Dutch Assemblies: The Conflict about the Hague". Legislative Studies Quarterly. 7 (2): 235–249. doi:10.2307/439669. JSTOR 439669.

- Haythornthwaite, Shavana. "The Peace of Breda (1667)". OPIL. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Israel, Jonathan (1989). Dutch Primacy in World Trade, 1585–1740 (1990 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198211396.

- Israel, Jonathan (1997). England's Mercantilist Response to Dutch World Trade Primacy, 1647–74 in Conflicts of Empires; Spain, the Low Countries and the struggle for World Supremacy 1585–1713. Hambledon Press. ISBN 978-1-85285-161-3.

- Kelsall, Philip (2008). Brand, Hanno; Müller, Leos (eds.). The changing relationship between Denmark and the Netherlands in The dynamics of economic culture in the North Sea- and Baltic region in the late Middle Ages and Early Modern period. Uitgeverij Verloren. ISBN 978-9065508829.

- Le Couteur, Penny; Burreson, Jay (2003). Napoleon's Buttons: How 17 Molecules Changed History. Jeremy Tarcher. ISBN 978-1585422203.

- Lesaffer, Randall (2016). De Vrede van Breda en de Europese traditie van vredesverdragen in Ginder 't Vreêverbont bezegelt : Essays over de betekenis van de Vrede van Breda 1667. Van Kemenade.

- Lee, Maurice D (1961). "The Earl of Arlington and the Treaty of Dover". Journal of British Studies. 1 (1): 58–70. doi:10.1086/385435. JSTOR 175099. S2CID 159658912.

- Lynn, John (1996). The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667–1714 (Modern Wars in Perspective). Longman. ISBN 978-0582056299.

- Newitt, Malyn (2004). A History of Portuguese Overseas Expansion 1400–1668. Routledge. ISBN 9781134553044.

- Pepys, Samuel (8 September 1667). "The Diary of Samuel Pepys; 8 September 1667". PepysDiary.com. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- Pincus, Steven CA (1996). Protestantism and Patriotism: Ideologies and the Making of English Foreign Policy, 1650-1668. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521434874.

- Rommelse, Gijs (2006). The Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665-1667): raison d'état, mercantilism and maritime strife. Uitgeverij Verloren. ISBN 978-9065509079.

- Sherman, Arnold A (1976). "Pressure from Leadenhall: The East India Company Lobby, 1660-1678". The Business History Review. 50 (3): 329–355. doi:10.2307/3112999. JSTOR 3112999. S2CID 154564220.

- Swart, KW (1969). The miracle of the Dutch Republic as seen in the seventeenth century;: An inaugural lecture delivered at University College London 6 November 1967. HK Lewis.

- Veenendaal, Augustus (1994). Hoffman, Philip (ed.). Fiscal Crises and Constitutional Freedom in the Netherlands, 1450–1795 in Fiscal Crises, Liberty and Representative Government, 1450–1789. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804722926.