Human height

Human height or stature is the distance from the bottom of the feet to the top of the head in a human body, standing erect. It is measured using a stadiometer,[1] in centimetres when using the metric system or SI system,[2][3] or feet and inches when using United States customary units or the imperial system.[4][5]

In the early phase of anthropometric research history, questions about height techniques for measuring nutritional status often concerned genetic differences.[6]

Height is also important because it is closely correlated with other health components, such as life expectancy.[6] Studies show that there is a correlation between small stature and a longer life expectancy. Individuals of small stature are also more likely to have lower blood pressure and are less likely to acquire cancer. The University of Hawaii has found that the "longevity gene" FOXO3 that reduces the effects of aging is more commonly found in individuals of small body size.[7] Short stature decreases the risk of venous insufficiency.[8]

When populations share genetic backgrounds and environmental factors, average height is frequently characteristic within the group. Exceptional height variation (around 20% deviation from average) within such a population is sometimes due to gigantism or dwarfism, which are medical conditions caused by specific genes or endocrine abnormalities.[9]

The development of human height can serve as an indicator of two key welfare components, namely nutritional quality and health.[10] In regions of poverty or warfare, environmental factors like chronic malnutrition during childhood or adolescence may result in delayed growth and/or marked reductions in adult stature even without the presence of any of these medical conditions.

Determinants of growth and height

The study of height is known as auxology.[11] Growth has long been recognized as a measure of the health of individuals, hence part of the reasoning for the use of growth charts. For individuals, as indicators of health problems, growth trends are tracked for significant deviations, and growth is also monitored for significant deficiency from genetic expectations. Genetics is a major factor in determining the height of individuals, though it is far less influential regarding differences among populations. Average height is relevant to the measurement of the health and wellness (standard of living and quality of life) of populations.[12]

Attributed as a significant reason for the trend of increasing height in parts of Europe are the egalitarian populations where proper medical care and adequate nutrition are relatively equally distributed.[13] The uneven distribution of nutritional resources makes it more plausible for individuals with better access to resources to grow taller, while individuals with worse access to resources have a lessened chance of growing taller.[14] Average height in a nation is correlated with protein quality. Nations that consume more protein in the form of meat, dairy, eggs, and fish tend to be taller, while those that obtain more protein from cereals tend to be shorter. Therefore, populations with high cattle per capita and high consumption of dairy live longer and are taller. Historically, this can be seen in the cases of the United States, Argentina, New Zealand and Australia in the beginning of the 19th century.[15] Moreover, when the production and consumption of milk and beef is taken to consideration, it can be seen why the Germanic people who lived outside of the Roman Empire were taller than those who lived at its heart.[16]

Changes in diet (nutrition) and a general rise in quality of health care and standard of living are the cited factors in the Asian populations. Malnutrition including chronic undernutrition and acute malnutrition is known to have caused stunted growth in various populations.[17] This has been seen in North Korea, parts of Africa, certain historical Europe, and other populations.[18] Developing countries such as Guatemala have rates of stunting in children under 5 living as high as 82.2% in Totonicapán, and 49.8% nationwide.[19]

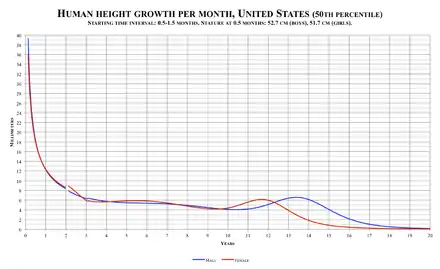

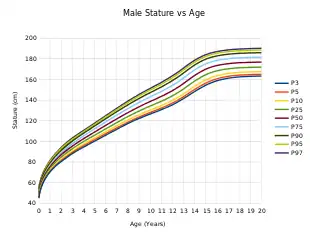

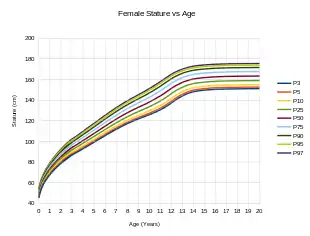

Height measurements are by nature subject to statistical sampling errors even for a single individual. In a clinical situation, height measurements are seldom taken more often than once per office visit, which may mean sampling taking place a week to several months apart. The smooth 50th percentile male and female growth curves illustrated above are aggregate values from thousands of individuals sampled at ages from birth to age 20. In reality, a single individual's growth curve shows large upward and downward spikes, partly due to actual differences in growth velocity, and partly due to small measurement errors.

For example, a typical measurement error of plus or minus 0.5 cm (0.2 in) may completely nullify 0.5 cm of actual growth resulting in either a "negative" 0.5 cm growth (due to overestimation in the previous visit combined with underestimation in the latter), up to a 1.5 cm (0.6 in) growth (the first visit underestimating and the second visit overestimating) in the same elapsed period between measurements. Note there is a discontinuity in the growth curves at age 2, which reflects the difference in recumbent length (with the child on his or her back), used in measuring infants and toddlers, and standing height typically measured from age 2 onwards.

Height, like other phenotypic traits, is determined by a combination of genetics and environmental factors. A child's height based on parental heights is subject to regression toward the mean, therefore extremely tall or short parents will likely have correspondingly taller or shorter offspring, but their offspring will also likely be closer to average height than the parents themselves. Genetic potential and several hormones, minus illness, is a basic determinant for height. Other factors include the genetic response to external factors such as diet, exercise, environment, and life circumstances.

Humans grow fastest (other than in the womb) as infants and toddlers, rapidly declining from a maximum at birth to roughly age 2, tapering to a slowly declining rate, and then, during the pubertal growth spurt (with an average girl starting her puberty and pubertal growth spurt at 10 years[20] and an average boy starting his puberty and pubertal growth spurt at 12 years[21][22]), a rapid rise to a second maximum (at around 11–12 years for an average female, and 13–14 years for an average male), followed by a steady decline to zero. The average female growth speed trails off to zero at about 15 or 16 years, whereas the average male curve continues for approximately 3 more years, going to zero at about 18–19, although there is limited research to suggest minor height growth after the age of 19 in males.[23] These are also critical periods where stressors such as malnutrition (or even severe child neglect) have the greatest effect.

Moreover, the health of a mother throughout her life, especially during her critical period and pregnancy, has a role. A healthier child and adult develops a body that is better able to provide optimal prenatal conditions.[18] The pregnant mother's health is essential for herself but also the fetus as gestation is itself a critical period for an embryo/fetus, though some problems affecting height during this period are resolved by catch-up growth assuming childhood conditions are good. Thus, there is a cumulative generation effect such that nutrition and health over generations influence the height of descendants to varying degrees.

The age of the mother also has some influence on her child's height. Studies in modern times have observed a gradual increase in height with maternal age, though these early studies suggest that trend is due to various socio-economic situations that select certain demographics as being more likely to have a first birth early in the mother's life.[24][25][26] These same studies show that children born to a young mother are more likely to have below-average educational and behavioural development, again suggesting an ultimate cause of resources and family status rather than a purely biological explanation.[25][26]

It has been observed that first-born males are shorter than later-born males.[27] However, more recently the reverse observation was made.[28] The study authors suggest that the cause may be socio-economic in nature.

Nature versus nurture

The precise relationship between genetics and environment is complex and uncertain. Differences in human height is 60–80% heritable, according to several twin studies[29] and has been considered polygenic since the Mendelian-biometrician debate a hundred years ago. A genome-wide association (GWA) study of more than 180,000 individuals has identified hundreds of genetic variants in at least 180 loci associated with adult human height.[30] The number of individuals has since been expanded to 253,288 individuals and the number of genetic variants identified is 697 in 423 genetic loci.[31] In a separate study of body proportion using sitting-height ratio, it reports that these 697 variants can be partitioned into 3 specific classes, (1) variants that primarily determine leg length, (2) variants that primarily determine spine and head length, or (3) variants that affect overall body size. This gives insights into the biological mechanisms underlying how these 697 genetic variants affect overall height.[32] These loci do not only determine height, but other features or characteristics. As an example, 4 of the 7 loci identified for intracranial volume had previously been discovered for human height.[33]

The effect of environment on height is illustrated by studies performed by anthropologist Barry Bogin and coworkers of Guatemala Mayan children living in the United States. In the early 1970s, when Bogin first visited Guatemala, he observed that Mayan Indian men averaged 157.5 centimetres (5 ft 2 in) in height and the women averaged 142.2 centimetres (4 ft 8 in). Bogin took another series of measurements after the Guatemalan Civil War, during which up to a million Guatemalans fled to the United States. He discovered that Maya refugees, who ranged from six to twelve years old, were significantly taller than their Guatemalan counterparts.[34] By 2000, the American Maya were 10.24 cm (4.03 in) taller than the Guatemalan Maya of the same age, largely due to better nutrition and health care.[35] Bogin also noted that American Maya children had relatively longer legs, averaging 7.02 cm (2.76 in) longer than the Guatemalan Maya (a significantly lower sitting height ratio).[35][36]

The Nilotic peoples of Sudan such as the Shilluk and Dinka have been described as some of the tallest in the world. Dinka Ruweng males investigated by Roberts in 1953–54 were on average 181.3 centimetres (5 ft 11+1⁄2 in) tall, and Shilluk males averaged 182.6 centimetres (6 ft 0 in).[37] The Nilotic people are characterized as having long legs, narrow bodies and short trunks, an adaptation to hot weather.[38] However, male Dinka and Shilluk refugees measured in 1995 in Southwestern Ethiopia were on average only 176.4 cm (5 ft 9+1⁄2 in) and 172.6 cm (5 ft 8 in) tall, respectively. As the study points out, Nilotic people "may attain greater height if privileged with favourable environmental conditions during early childhood and adolescence, allowing full expression of the genetic material."[39] Before fleeing, these refugees were subject to privation as a consequence of the succession of civil wars in their country from 1955 to the present.

The tallest living married couple are ex-basketball players Yao Ming and Ye Li (both of China) who measure 228.6 cm (7 ft 6 in) and 190.5 cm (6 ft 3 in) respectively, giving a combined height of 419.1 cm (13 ft 9 in). They married in Shanghai, China, on 6 August 2007.[40]

In Tibet, the Khampas are known for their great height. Khampa males are on average 180 cm (5 ft 11 in).[41][42]

Role of an individual's height

Height and health

Studies show that there is a correlation between small stature and a longer life expectancy. Individuals of small stature are also more likely to have lower blood pressure and are less likely to acquire cancer. The University of Hawaii has found that the "longevity gene" FOXO3 that reduces the effects of aging is more commonly found in individuals of a small body size.[7] Short stature decreases the risk of venous insufficiency.[8] Certain studies have shown that height is a factor in overall health while some suggest tallness is associated with better cardiovascular health and shortness with longevity.[43] Cancer risk has also been found to grow with height.[44] Moreover, scientists have also observed a protective effect of height on risk for Alzheimer's disease, although this fact could be a result of the genetic overlap between height and intracraneal volume and there are also genetic variants influencing height that could affect biological mechanisms involved in Alzheimer's disease etiology, such as insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1).[45]

Nonetheless, modern westernized interpretations of the relationship between height and health fail to account for the observed height variations worldwide.[46] Cavalli-Sforza and Cavalli-Sforza note that variations in height worldwide can be partly attributed to evolutionary pressures resulting from differing environments. These evolutionary pressures result in height-related health implications. While tallness is an adaptive benefit in colder climates such as those found in Europe, shortness helps dissipate body heat in warmer climatic regions.[46] Consequently, the relationships between health and height cannot be easily generalized since tallness and shortness can both provide health benefits in different environmental settings.

In the end, being excessively tall can cause various medical problems, including cardiovascular problems, because of the increased load on the heart to supply the body with blood, and problems resulting from the increased time it takes the brain to communicate with the extremities. For example, Robert Wadlow, the tallest man known to verifiable history, developed trouble walking as his height increased throughout his life. In many of the pictures of the latter portion of his life, Wadlow can be seen gripping something for support. Late in his life, although he died at age 22, he had to wear braces on his legs and walk with a cane; and he died after developing an infection in his legs because he was unable to feel the irritation and cutting caused by his leg braces.

Sources are in disagreement about the overall relationship between height and longevity. Samaras and Elrick, in the Western Journal of Medicine, demonstrate an inverse correlation between height and longevity in several mammals including humans.[43]

Women whose height is under 150 cm (4 ft 11 in) may have a small pelvis, resulting in such complications during childbirth as shoulder dystocia.[47]

A study done in Sweden in 2005 has shown that there is a strong inverse correlation between height and suicide among Swedish men.[48]

A large body of human and animal evidence indicates that shorter, smaller bodies age more slowly, and have fewer chronic diseases and greater longevity. For example, a study found eight areas of support for the "smaller lives longer" thesis. These areas of evidence include studies involving longevity, life expectancy, centenarians, male vs. female longevity differences, mortality advantages of shorter people, survival findings, smaller body size due to calorie restriction, and within-species body size differences. They all support the conclusion that smaller individuals live longer in healthy environments and with good nutrition. However, the difference in longevity is modest. Several human studies have found a loss of 0.5 years/centimeter of increased height (1.2 yr/inch). But these findings do not mean that all tall people die young. Many live to advanced ages and some become centenarians.[49]

In medicine, height is measured to monitor child development, this is a better indicator of growth than weight in the long term.[50] For older people, excessive height loss is a symptom of osteoporosis.[51] Height is also used to compute indicators like body surface area or body mass index.

Height and occupational success

There is a large body of research in psychology, economics, and human biology that has assessed the relationship between several physical features (e.g., body height) and occupational success.[52] The correlation between height and success was explored decades ago.[53][54] Shorter people are considered to have an advantage in certain sports (e.g., gymnastics, race car driving, etc.), whereas in many other sports taller people have a major advantage. In most occupational fields, body height is not relevant to how well people are able to perform; nonetheless several studies found that success was positively correlated with body height, although there may be other factors such as sex or socioeconomic status that are correlated with height which may account for the difference in success.[52][53][55][56]

A demonstration of the height-success association can be found in the realm of politics. In the United States presidential elections, the taller candidate won 22 out of 25 times in the 20th century.[57] Nevertheless, Ignatius Loyola, founder of the Jesuits, was 150 cm (4 ft 11 in) and several prominent world leaders of the 20th century, such as Vladimir Lenin, Benito Mussolini, Nicolae Ceaușescu and Joseph Stalin were of below-average height. These examples, however, were all before modern forms of multi-media, i.e., television, which may further height discrimination in modern society. Further, growing evidence suggests that height may be a proxy for confidence, which is likewise strongly correlated with occupational success.[58]

Sports

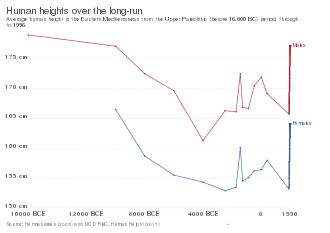

Human height throughout history

In general, modern humans living in developed countries are taller than their ancient counterparts, but this was not always the case. Certain ancient human populations were quite tall, even surpassing the average height of the tallest of modern countries. For instance, hunter-gatherer populations living in Europe during the Paleolithic Era and India during the Mesolithic Era averaged heights of around 183 cm (6 ft 0 in) for males, and 172 cm (5 ft 7+1⁄2 in) for females.[59]

Human height worldwide sharply declined with the advent of the Neolithic revolution, likely due to significantly less protein consumption by agriculturalists as compared with hunter-gatherers.

During the Bronze Age, height varied significantly by region. The people of the Indus Valley Civilization were among the tallest in the world, with an average height of 175.8 cm (5 ft 9 in) for males and 166.1 cm (5 ft 5+1⁄2 in) for females. The people of Ancient Egypt stood around 167.9 cm (5 ft 6 in) for males and 157.5 cm (5 ft 2 in) for females.[60] The Ancient Greeks averaged 166.8 cm (5 ft 5+1⁄2 in) for males and 154.5 cm (5 ft 1 in) for females. The Romans were slightly taller, with an average height of 169.2 cm (5 ft 6+1⁄2 in) for males and 158 cm (5 ft 2 in) for females.[61]

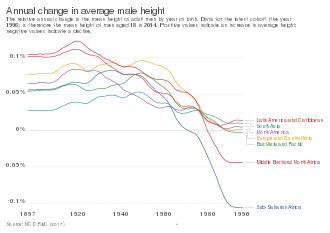

In the 150 years since the mid-nineteenth century, the average human height in industrialised countries has increased by up to 10 centimetres (3.9 in).[62] However, these increases appear to have largely levelled off.[62][63] Before the mid-nineteenth century, there were cycles in height, with periods of increase and decrease;[64] however, apart from the decline associated with the transition to agriculture, examinations of skeletons show no significant differences in height from the Neolithic Revolution through the early-1800s.[65][66]

In general, there were no significant differences in regional height levels throughout the nineteenth century.[67] The only exceptions of this rather uniform height distribution were people in the Anglo-Saxon settlement regions who were taller than the average and people from Southeast Asia with below-average heights. However, at the end of the nineteenth century and in the middle of the first globalization period, heights between rich and poor countries began to diverge.[68] These differences did not disappear in the deglobalization period of the two World wars. Baten and Blum (2014) [69] find that in the nineteenth century, important determinants of height were the local availability of cattle, meat and milk as well as the local disease environment. In the late twentieth century, however, technologies and trade became more important, decreasing the impact of local availability of agricultural products.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, people of European descent in North America were far taller than those in Europe and were the tallest in the world.[13] The original indigenous population of Plains Native Americans was also among the tallest populations of the world at the time.[70]

Some studies also suggest that there existed the correlation between the height and the real wage, moreover, the correlation was higher among the less developed countries. The difference in height between children from different social classes was already observed by the age of two.[71]

In the late nineteenth century, the Netherlands was a land renowned for its short population, but today Dutch people are among the world's tallest, with young men averaging 183.8 cm (6 ft 0.4 in) tall.[72]

According to a study by economist John Komlos and Francesco Cinnirella, in the first half of the eighteenth century, the average height of an English male was 165 cm (5 ft 5 in), and the average height of an Irish male was 168 cm (5 ft 6 in). The estimated mean height of English, German, and Scottish soldiers was 163.6 cm (5 ft 4+1⁄2 in) – 165.9 cm (5 ft 5+1⁄2 in) for the period as a whole, while that of Irish was 167.9 cm (5 ft 6 in). The average height of male slaves and convicts in North America was 171 cm (5 ft 7+1⁄2 in).[73]

The average height of Americans and Europeans decreased during periods of rapid industrialization, possibly due to rapid population growth and broad decreases in economic status.[74] This has become known as the early-industrial growth puzzle (in the U.S. context the Antebellum Puzzle). In England during the early nineteenth century, the difference between the average height of English upper-class youth (students of Sandhurst Military Academy) and English working-class youth (Marine Society boys) reached 22 cm (8+1⁄2 in), the highest that has been observed.[75]

Data derived from burials show that before 1850, the mean stature of males and females in Leiden, The Netherlands was respectively 167.7 cm (5 ft 6 in) and 156.7 cm (5 ft 1+1⁄2 in). The average height of 19-year-old Dutch orphans in 1865 was 160 cm (5 ft 3 in).[76]

According to a study by J.W. Drukker and Vincent Tassenaar, the average height of a Dutch person decreased from 1830 to 1857, even while Dutch real GNP per capita was growing at an average rate of more than 0.5% per year. The worst decline was in urban areas that in 1847, the urban height penalty was 2.5 cm (1.0 in). Urban mortality was also much higher than in rural regions. In 1829, the average urban and rural Dutchman was 164 cm (5 ft 4+1⁄2 in). By 1856, the average rural Dutchman was 162 cm (5 ft 4 in) and urban Dutchman was 158.5 cm (5 ft 2+1⁄2 in).[77]

A 2004 report citing a 2003 UNICEF study on the effects of malnutrition in North Korea, due to "successive famines," found young adult males to be significantly shorter. In contrast South Koreans "feasting on an increasingly Western-influenced diet," without famine, were growing taller. The height difference is minimal for Koreans over forty years old, who grew up at a time when economic conditions in the North were roughly comparable to those in the South, while height disparities are most acute for Koreans who grew up in the mid-1990s – a demographic in which South Koreans are about 12 cm (4.7 in) taller than their North Korean counterparts – as this was a period during which the North was affected by a harsh famine where hundreds of thousands, if not millions, died of hunger.[78] A study by South Korean anthropologists of North Korean children who had defected to China found that eighteen-year-old males were 13 centimetres (5 in) shorter than South Koreans their age due to malnutrition.[79]

The tallest living man is Sultan Kösen of Turkey at 251 cm (8 ft 3 in) and the tallest living woman is Siddiqa Parveen of India at 234 cm (7 ft 8 in). The tallest man in modern history was Robert Pershing Wadlow (1918–1940), from Illinois, United States, who was 272 cm (8 ft 11 in) at the time of his death. The tallest woman in medical history was Trijntje Keever of Edam, Netherlands, who stood 254 cm (8 ft 4 in) when she died at the age of seventeen. The shortest adult human on record was Chandra Bahadur Dangi of Nepal at 54.6 cm (1 ft 9+1⁄2 in).

Adult height between populations often differs significantly. For example, the average height of women from the Czech Republic is greater than that of men from Malawi. This may be caused by genetic differences, childhood lifestyle differences (nutrition, sleep patterns, physical labor), or both.

Depending on sex, genetic and environmental factors, shrinkage of stature may begin in middle age in some individuals but tends to be universal in the extremely aged. This decrease in height is due to such factors as decreased height of inter-vertebral discs because of desiccation, atrophy of soft tissues, and postural changes secondary to degenerative disease.

Working on data of Indonesia, the study by Baten, Stegl and van der Eng suggests a positive relationship of economic development and average height. In Indonesia, human height has decreased coincidentally with natural or political shocks.[80]

Average height around the world

.jpg.webp)

As with any statistical data, the accuracy of such data may be questionable for various reasons:

- Some studies may allow subjects to self-report values. Generally speaking, self-reported height tends to be taller than its measured height, although the overestimation of height depends on the reporting subject's height, age, gender and region.[81][82][83][84]

- Test subjects may have been invited instead of chosen randomly, resulting in sampling bias.

- Some countries may have significant height gaps between different regions. For instance, one survey shows there is 10.8 centimetres (4.3 in) gap between the tallest state and the shortest state in Germany.[85] Under such circumstances, the mean height may not represent the total population unless sample subjects are appropriately taken from all regions with using weighted average of the different regional groups.

- Different social groups can show different mean height. According to a study in France, executives and professionals are 2.6 centimetres (1.0 in) taller, and university students are 2.55 centimetres (1.0 in) taller than the national average.[86] As this case shows, data taken from a particular social group may not represent a total population in some countries.

- A relatively small sample of the population may have been measured, which makes it uncertain whether this sample accurately represents the entire population.

- The height of persons can vary over a day, because of factors such as a height increase from exercise done directly before measurement (normally inversely correlated), or a height increase since lying down for a significant period (normally inversely correlated). For example, one study revealed a mean decrease of 1.54 centimetres (0.6 in) in the heights of 100 children from getting out of bed in the morning to between 4 and 5 p.m. that same day.[87] Such factors may not have been controlled in some of the studies.

- Men from Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Netherlands, Croatia, Serbia and Montenegro have the tallest average height.[88][89]

- Dinka people are sometimes noted for their height. With the Tutsi of Rwanda, they are believed to be the tallest people in Africa.[90] Roberts and Bainbridge reported the average height of 182.6 cm (5 ft 11.9 in) in a sample of 52 Dinka Agaar and 181.3 cm (5 ft 11.4 in) in 227 Dinka Ruweng measured in 1953–1954.[91] Other studies of comparative historical height data and nutrition place the Dinka as the tallest people in the world.[92]

Measurement

Crown-rump length is the measurement of the length of human embryos and fetuses from the top of the head (crown) to the bottom of the buttocks (rump). It is typically determined from ultrasound imagery and can be used to estimate gestational age.

Until two years old, recumbent length is used to measure infants.[93] Length measures the same dimension as height, but height is measured standing up while the length is measured lying down. In developed nations, the average total body length of a newborn is about 50 cm (20 in), although premature newborns may be much smaller.

Standing height is used to measure children over two years old[94] and adults who can stand without assistance. Measure is done with a stadiometer. In general, standing height is about 0.7 cm (0.3 in) less than recumbent length.[95]

Surrogate height measurements are used when standing height and recumbent length are impractical. For sample Chumlea equation use knee height as indicator of stature.[96] Other techniques include: arm span, sitting height, ulna length, etc.

See also

- Anthropometry, the measurement of the human individual

- Human body weight

- List of tallest people

- Economics and Human Biology (academic journal)

- History of anthropometry

- Human physical appearance

- Human variability

- Pygmy peoples

Citations

- "Stadiometers and Height Measurement Devices". stadiometer.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- "Using the BMI-for-Age Growth Charts". cdc.gov. Centers for Disease Control. Archived from the original on 30 January 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- Price, Beth; et al. (2009). MathsWorld Year 8 VELS Edition. Australia: MacMillan. p. 626. ISBN 978-0-7329-9251-4.

- Lapham, Robert; Agar, Heather (2009). Drug Calculations for Nurses. USA: Taylor & Francis. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-340-98733-9.

- Carter, Pamela J. (2008). Lippincott's Textbook for Nursing Assistants: A Humanistic Approach to Caregiving. USA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. p. 306. ISBN 978-0-7817-6685-2.

- Baten, Joerg; Matthias, Blum (2012). "Growing Tall: Anthropometric Welfare of World Regions and its Determinants, 1810–1989". Economic History of Developing Regions. 27. doi:10.1080/20780389.2012.657489. S2CID 154506540 – via Researchgate.

- "Shorter men live longer, study shows".

- "Tall height".

- Ganong, William F. (2001) Review of Medical Physiology, Lange Medical, pp. 392–397, ISBN 0071605673.

- Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-50718-0.

- Hermanussen, Michael (ed) (2013) Auxology – Studying Human Growth and Development, Schweizerbart, ISBN 9783510652785.

- Bolton-Smith, C. (2000). "Accuracy of the estimated prevalence of obesity from self reported height and weight in an adult Scottish population". Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 54 (2): 143–148. doi:10.1136/jech.54.2.143. PMC 1731630. PMID 10715748.

- Komlos, J.; Baur, M. (2004). "From the tallest to (one of) the fattest: The enigmatic fate of the American population in the 20th century". Economics & Human Biology. 2 (1): 57–74. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.651.9270. doi:10.1016/j.ehb.2003.12.006. PMID 15463993. S2CID 14291466.

- Baten, Joerg; Moradi, Alexander (2005). "Inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa: New Data and New Insights from Anthropometric Estimates". World Development. 33 (8): 1233–1265. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.04.010.

- Baten, Jörg; Blum, Matthias (2012). "An Anthropometric History of the World, 1810–1980: Did Migration and Globalization Influence Country Trends?". Journal of Anthropological Sciences. 90 (90): 221–4. doi:10.4436/jass.90011. PMID 23011935. S2CID 38889880.

- Baten, Joerg; Koepke, Nikola (2008). "Agricultural Specialization and Height in Ancient and Medieval Europe". Explorations in Economic History. 45 (2): 127. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2007.09.003.

- De Onis, M.; Blössner, M.; Borghi, E. (2011). "Prevalence and trends of stunting among pre-school children, 1990–2020". Public Health Nutrition. 15 (1): 142–148. doi:10.1017/S1368980011001315. PMID 21752311.

- Grantham-Mcgregor, S.; Cheung, Y. B.; Cueto, S.; Glewwe, P.; Richter, L.; Strupp, B. (2007). "Developmental potential in the first 5 years for children in developing countries". The Lancet. 369 (9555): 60–70. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60032-4. PMC 2270351. PMID 17208643.

- Encuesta Nacional de Salud Materno Infantil, 2008‒2009 [Guatemala Reproductive Health Survey 2008‒2009] (PDF). Guatemala City, Guatemala: Ministerio de Salud Pública y Asistencia Social. December 2010. p. 670. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- "Early Puberty in Girls". Nationwide Children's. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- "Early Puberty in Boys". Nationwide Children's. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- "Is Your Child Growing Normally?". THE MAGIC FOUNDATION. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Hulanicka, B.; Kotlarz, K. (1983). "The final phase of growth in height". Annals of Human Biology. 10 (5): 429–433. doi:10.1080/03014468300006621. ISSN 0301-4460. PMID 6638938.

- Table 1. Association of 'biological' and demographic variables and height. Figures are coefficients (95% confidence intervals) adjusted for each of the variables shown in Rona RJ, Mahabir D, Rocke B, Chinn S, Gulliford MC (2003). "Social inequalities and children's height in Trinidad and Tobago". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 57 (1): 143–50. doi:10.1038/SJ.ejcn.1601508. PMID 12548309.

- Miller, Jane E. (1993). "Birth Outcomes by Mother's Age At First Birth in the Philippines". International Family Planning Perspectives. 19 (3): 98–102. doi:10.2307/2133243. JSTOR 2133243.

- Pevalin, David J. (2003). "Outcomes in Childhood and Adulthood by Mother's Age at Birth: evidence from the 1970 British Cohort Study". ISER Working Papers.

- Hermanussen, M.; Hermanussen, B.; Burmeister, J. (1988). "The association between birth order and adult stature". Annals of Human Biology. 15 (2): 161–165. doi:10.1080/03014468800009581. PMID 3355105.

- Myrskyla, M (July 2013). "The association between height and birth order: evidence from 652,518 Swedish men". Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 67 (7): 571–7. doi:10.1136/jech-2012-202296. PMID 23645856. S2CID 19510422.

- Lai, Chao-Qiang (11 December 2006). "How much of human height is genetic and how much is due to nutrition?". Scientific American.

- Lango Allen H, et al. (2010). "Hundreds of variants clustered in genomic loci and biological pathways affect human height". Nature. 467 (7317): 832–838. Bibcode:2010Natur.467..832L. doi:10.1038/nature09410. PMC 2955183. PMID 20881960.

- Wood AR, et al. (2014). "Defining the role of common variation in the genomic and biological architecture of adult human height". Nature Genetics. 46 (11): 1173–1186. doi:10.1038/ng.3097. PMC 4250049. PMID 25282103.

- Chan Y, et al. (2015). "Genome-wide Analysis of Body Proportion Classifies Height-Associated Variants by Mechanism of Action and Implicates Genes Important for Skeletal Development". American Journal of Human Genetics. 96 (5): 695–708. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.02.018. PMC 4570286. PMID 25865494.

- Adams, Hieab H H; Hibar, Derrek P; Chouraki, Vincent; Stein, Jason L; Nyquist, Paul A; Rentería, Miguel E; Trompet, Stella; Arias-Vasquez, Alejandro; Seshadri, Sudha (2016). "Novel genetic loci underlying human intracranial volume identified through genome-wide association". Nature Neuroscience. 19 (12): 1569–1582. doi:10.1038/nn.4398. PMC 5227112. PMID 27694991.

- Bogin, Barry (1998). "The tall and the short of it". Discover. 19 (2): 40–44. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Bogin, B.; Rios, L. (2003). "Rapid morphological change in living humans: Implications for modern human origins". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A. 136 (1): 71–84. doi:10.1016/S1095-6433(02)00294-5. PMID 14527631.

- Krawitz, Jan (28 June 2006). "P.O.V. – Big Enough". PBS. Archived from the original on 30 April 2009. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- Roberts, D. F.; Bainbridge, D. R. (1963). "Nilotic physique". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 21 (3): 341–370. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330210309. PMID 14159970.

- Stock, Jay (Summer 2006). "Skeleton key" (PDF). Planet Earth: 26. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2007.

- Chali D (1995). "Anthropometric measurements of the Nilotic tribes in a refugee camp". Ethiopian Medical Journal. 33 (4): 211–7. PMID 8674486.

- Guinness World Records 2014. The Jim Pattison Group. 2013. p. 49.

- Subba, Tanka Bahadur (1999). Politics of Culture: A Study of Three Kirata Communities in the Eastern Himalayas. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-81-250-1693-9.

- Peissel, Michel (1967). Mustang: A Lost Tibetan Kingdom. Book Faith India. ISBN 978-81-7303-002-4.

- Samaras TT, Elrick H (2002). "Height, body size, and longevity: is smaller better for the humanbody?". The Western Journal of Medicine. 176 (3): 206–8. doi:10.1136/ewjm.176.3.206. PMC 1071721. PMID 12016250.

- "Cancer risk may grow with height". CBC News. 21 July 2011.

- Jansen, I.E.; Savage, J.E.; Watanabe, K.; Bryois, J.; Williams, D.M.; Steinberg, S.; Sealock, J.; Karlsson, I.K.; Hägg, S. (2019). "Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new loci and functional pathways influencing Alzheimer's disease risk". Nature Genetics. 51 (3): 404–413. doi:10.1038/s41588-018-0311-9. hdl:10037/17318. PMC 6836675. PMID 30617256.

- Cavalli-Sforza, L.L., & Cavalli-Sforza, F., 1995, The Great Human Diasporas,

- Merck. "Risk factors present before pregnancy". Merck Manual Home Edition. Merck Sharp & Dohme.

- Magnusson PK, Gunnell D, Tynelius P, Davey Smith G, Rasmussen F (2005). "Strong inverse association between height and suicide in a large cohort of Swedish men: evidence of early life origins of suicidal behavior?". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 162 (7): 1373–5. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1373. PMID 15994722.

- Samaras TT 2014, Evidence from eight studies showing smaller body size is related to greater longevity JSRR 3(16):2150-2160. 2014: article no. JSRR.2014.16.003

- "3. Growth and development".

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Stefan, Stieger; Christoph, Burger (2010). "Body height and occupational success for actors and actresses". Psychological Reports. 107 (1): 25–38. doi:10.2466/pr0.107.1.25-38. PMID 20923046.

- W. E., Hensley; R., Cooper (1987). "Height and occupational success: a review and critique". Psychological Reports. 60 (3 Pt 1): 843–849. doi:10.2466/pr0.1987.60.3.843. PMID 3303094. S2CID 8160354.

- Judge, T. A.; Cable, D. M. (2004). "The Effect of Physical Height on Workplace Success and Income: Preliminary Test of a Theoretical Model" (PDF). Journal of Applied Psychology. 89 (3): 428–441. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.89.3.428. PMID 15161403. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 September 2012.

- Nicola, Persico; Andrew, Postlewaite; Silverman, Dan (2004). "The Effect of Adolescent Experience on Labor Market Outcomes: The Case of Height" (PDF). Journal of Political Economy. 112 (5): 1019–1053. doi:10.1086/422566. S2CID 158048477.

- Heineck G. (2005). "Up in the skies? The relationship between body height and earnings in Germany" (PDF). Labour. 19 (3): 469–489. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9914.2005.00302.x. S2CID 18176180.

- Piotr, Sorokowski (2010). "Politicians' estimated height as an indicator of their popularity". European Journal of Social Psychology. 40 (7): 1302–1309. doi:10.1002/ejsp.710.

- Nickless, Rachel (28 November 2012) Lifelong confidence rewarded in bigger pay packets. Afr.com. Retrieved on 2 September 2013.

- Lukacs, John R.; Pal, J. N. (2003). "Skeletal Variation among Mesolithic People of the Ganga Plains: New Evidence of Habitual Activity and Adaptation to Climate" (PDF). Asian Perspectives. 42 (2): 329–351. doi:10.1353/asi.2003.0042. JSTOR 42928583. S2CID 161294454.

- Zakrzewski, SR (July 2003). "Variation in ancient Egyptian stature and body proportions" (PDF). American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 121 (3): 219–29. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10223. PMID 12772210. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Hermanussen, M. (2003). "Stature of early Europeans". Hormones. 2 (3): 175–178. doi:10.14310/horm.2002.1199. PMID 17003019.

- Adam Hadhazy (14 May 2015). "Will humans keep getting taller?". BBC. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- Michael J. Dougherty. "Why are we getting taller as a species?". Scientific American. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- Laura Blue (8 July 2008). "Why Are People Taller Today Than Yesterday?". Time. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- Herrera, Rene J.; Garcia-Bertrand, Ralph (13 June 2018). Ancestral DNA, Human Origins, and Migrations. Academic Press. p. 501. ISBN 978-0-12-804128-4.

- Wells, Jonathan C. K.; Stock, Jay T. (2020). "Life History Transitions at the Origins of Agriculture: A Model for Understanding How Niche Construction Impacts Human Growth, Demography and Health". Frontiers in Endocrinology. 11: 325. doi:10.3389/fendo.2020.00325. ISSN 1664-2392. PMC 7253633. PMID 32508752.

- Baten, Joerg; Blum, Matthias (2012). "Growing tall but unequal: new findings and new background evidence on anthropometric welfare in 156 countries, 1810–1989". Economic History of Developing Regions. 27: S66–S85. doi:10.1080/20780389.2012.657489. S2CID 154506540.

- Baten, Joerg (2006). "Global Height Trends in Industrial and Developing Countries, 1810–1984: An Overview". Recuperado el. 20.

- Baten, Joerg; Blum, Matthias (2014). "Why are you tall while others are short? Agricultural production and other proximate determinants of global heights". European Review of Economic History. 18 (2): 144–165. doi:10.1093/ereh/heu003.

- Prince, Joseph M.; Steckel, Richard H. (December 1998). "The Tallest in the World: Native Americans of the Great Plains in the Nineteenth Century". NBER Historical Working Paper No. 112. doi:10.3386/h0112.

- Baten, Jörg (June 2000). "Heights and Real Wages in the 18th and 19th Centuries: An International Overview". Economic History Yearbook. 41 (1). doi:10.1524/jbwg.2000.41.1.61. S2CID 154826434.

- Schönbeck, Yvonne; Talma, Henk; Van Dommelen, Paula; Bakker, Boudewijn; Buitendijk, Simone E.; Hirasing, Remy A.; Van Buuren, Stef (2012). "The world's tallest nation has stopped growing taller: The height of Dutch children from 1955 to 2009". Pediatric Research. 73 (3): 371–7. doi:10.1038/pr.2012.189. PMID 23222908.

- Komlos, John; Francesco Cinnirella (2007). "European heights in the early 18th century". Vierteljahrschrift für Sozial-und Wirtschaftsgeschichte. 94 (3): 271–284. doi:10.25162/vswg-2007-0015. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Komlos, John (1998). "Shrinking in a growing economy? The mystery of physical stature during the industrial revolution". Journal of Economic History. 58 (3): 779–802. doi:10.1017/S0022050700021161. S2CID 3557631.

- Komlos, J. (2007). On English Pygmies and Giants: The physical stature of English youth in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Research in Economic History. Vol. 25. pp. 149–168. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.539.620. doi:10.1016/S0363-3268(07)25003-7. ISBN 978-0-7623-1370-9.

- Fredriks, Anke Maria (2004). Growth diagrams: fourth Dutch nation-wide survey. Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum. ISBN 9789031343478.

- Drukker, J. W.; Vincent Tassenaar (2000). "Shrinking Dutchmen in a growing economy: the early industrial growth paradox in the Netherlands" (PDF). Jahrbuch für Wirtschaftsgeschichte. 2000: 77–94. ISSN 0075-2800. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Demick, Barbara (14 February 2004). "Effects of famine: Short stature evident in North Korean generation". Seattle Times. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Demick, Barbara (8 October 2011). "The unpalatable appetites of Kim Jong-il". Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- van der Eng, Pierre; Baten, Joerg; Stegl, Mojgan (2010). "Long-Term Economic Growth and the Standard of Living in Indonesia" (PDF). SSRN Electronic Journal. Elsevier BV. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1699972. ISSN 1556-5068. S2CID 127728911.

- Arno J. Krul; Hein A. M. Daanen; Hyegjoo Choi (2010). "Self-reported and measured weight, height and body mass index (BMI) in Italy, the Netherlands and North America". European Journal of Public Health. 21 (4): 414–419. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckp228. PMID 20089678.

- Lucca A, JMoura EC (2010). "Validity and reliability of self-reported weight, height and body mass index from telephone interviews" (PDF). Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 26 (1): 110–22. doi:10.1590/s0102-311x2010000100012. PMID 20209215.

- Shields, Margot; Gorber, Sarah Connor; Tremblay, Mark S. (2009). "Methodological Issues in Anthropometry: Self-reported versus Measured Height and Weight" (PDF). Component of Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11-522-X. Statistics Canada’s International Symposium Series: Proceedings Symposium 2008. Proceedings of Statistics Canada Symposium 2008. Data Collection: Challenges, Achievements and New Directions. Methodological Issues in Anthropometry: Self-reported versus Measured Height and Weight.

- Moody, Alison (18 December 2013). "10: Adult anthropometric measures, overweight and obesity". In Craig, Rachel; Mindell, Jennifer (eds.). Health Survey for England – 2012 (PDF) (Report). Vol. 1: Health, social care and lifestyles. Health and Social Care Information Centre. p. 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 July 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- WWC Web World Center GmbH G.R.P. Institut für Rationelle Psychologie KÖRPERMASSE BUNDESLÄNDER & STÄDTE Archived 16 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine 31. Oktober 2007

- Herpin, Nicolas (2003). "La taille des hommes: son incidence sur la vie en couple et la carrière professionnelle" (PDF). Économie et Statistique. 361 (1): 71–90. doi:10.3406/estat.2003.7355.

- Buckler, JM (1978). "Variations in height throughout the day". Arch Dis Child. 53 (9): 762. doi:10.1136/adc.53.9.762. PMC 1545095. PMID 568918.

- Grasgruber, Pavel; Popović, Stevo; Bokuvka, Dominik; Davidović, Ivan; Hřebíčková, Sylva; Ingrová, Pavlína; Potpara, Predrag; Prce, Stipan; Stračárová, Nikola (1 April 2017). "The mountains of giants: an anthropometric survey of male youths in Bosnia and Herzegovina". Royal Society Open Science. 4 (4): 161054. Bibcode:2017RSOS....461054G. doi:10.1098/rsos.161054. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 5414258. PMID 28484621.

- Viegas, Jen (11 April 2017). "The Tallest Men in the World Trace Back to Paleolithic Mammoth Hunters". seeker. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- "The Tutsi". In and Out of Focus: Images from Central Africa 1885–1960. National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- Roberts, D. F.; Bainbridge, D. R. (1963). "Nilotic physique". Am J Phys Anthropol. 21 (3): 341–370. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330210309. PMID 14159970.

- Eveleth and Tanner (1976) Worldwide Variation in Human Growth, Cambridge University Press; --Floud et al 1990 Height, Health and History: Nutritional Status in the United Kingdom, 1750–1980, p. 6

- "Infant Guidelines".

- "Child Guidelines".

- Measuring a child's growth p.19, World Health Organization

- Berger, Mette M.; Cayeux, Marie-Christine; Schaller, Marie-Denise; Soguel, Ludivine; Piazza, Guido; Chioléro, René L. (2008). "Stature estimation using the knee height determination in critically ill patients". e-SPEN, the European e-Journal of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism. 3 (2): e84–e88. doi:10.1016/j.eclnm.2008.01.004.

General and cited bibliography

- "Los españoles somos 3,5 cm más altos que hace 20 años" [Spaniards are 3.5 cm taller than 20 years ago]. 20 minutos (in Spanish). 31 July 2006.

- Aminorroaya, A.; Amini, M.; Naghdi, H. & Zadeh, A. H. (2003). "Growth charts of heights and weights of male children and adolescents of Isfahan, Iran" (PDF). Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition. 21 (4): 341–346. PMID 15038589. S2CID 21907084. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 September 2018.

- Bilger, Burkhard (29 March 2004). "The Height Gap". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 2 April 2004.

- Bogin, Barry (2001). The Growth of Humanity. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Liss. ISBN 978-0-471-35448-2.

- Case, A. & Paxson, C. (2008). "Stature and Status: Height, ability, and labor market outcomes". The Journal of Political Economy. 116 (3): 499–532. doi:10.1086/589524. PMC 2709415. PMID 19603086.

- "Health Survey for England – trend data". United Kingdom: Department of Health and Social Care. Archived from the original on 10 October 2004.

- Eurostat Statistical Yearbook 2004. Luxembourg: Eurostat. 2014. ISBN 978-92-79-38906-1. (for heights in Germany)

- Eveleth, P. B.; Tanner, J. M. (1990). Worldwide Variation in Human Growth (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-35916-0.

- Grandjean, Etienne (1987). Fitting the Task to the Man: An Ergonomic Approach. London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-85066-192-7. (for heights in U.S. and Japan)

- Habicht, Michael E.; Henneberg, Maciej; Öhrström, Lena M.; Staub, Kaspar & Rühli, Frank J. (27 April 2015). "Body height of mummified pharaohs supports historical suggestions of sibling marriages". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 157 (3): 519–525. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22728. PMID 25916977. S2CID 205335354.

- A collection of data on human height, referred to here as "karube" but originally collected from other sources, is archived here. A copy is available here (an English translation of this Japanese page would make it easier to evaluate the quality of the data...)

- Krishan, K. & Sharma, J. C. (2002). "Intra-individual difference between recumbent length and stature among growing children". Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 69 (7): 565–569. doi:10.1007/BF02722678. PMID 12173694. S2CID 22427304.

- Miura, K.; Nakagawa, H. & Greenland, P. (2002). "Invited commentary: Height-cardiovascular disease relation: where to go from here?". American Journal of Epidemiology. 155 (8): 688–689. doi:10.1093/aje/155.8.688. PMID 11943684.

- "Americans Slightly Taller, Much Heavier Than Four Decades Ago". National Center for Health Statistics. 27 October 2004.

- Netherlands Central Bureau for Statistics, 1996 (for average heights)

- Ogden, Cynthia L.; Fryar, Cheryl D.; Carroll, Margaret D. & Flegal, Katherine M. (27 October 2004). "Mean Body Weight, Height, and Body Mass Index, United States 1960–2002" (PDF). Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics (347): 1–17. PMID 15544194.

- Ruff, Christopher (October 2002). "Variation in human body size and shape". Annual Review of Anthropology. 31: 211–232. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.31.040402.085407.

- Sakamaki, R.; Amamoto, R.; Mochida, Y.; Shinfuku, N. & Toyama, K. (2005). "A comparative study of food habits and body shape perception of university students in Japan and Korea". Nutrition Journal. 4: 31. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-4-31. PMC 1298329. PMID 16255785.

- 6. Celostátní antropologický výzkum dětí a mládeže 2001, Česká republika [6th Nationwide anthropological research of children and youth 2001, Czech Republic] (in Czech). Prague: Státní zdravotní ústav (SZÚ; "State Health Institute"). 2005. ISBN 978-8-07071-251-1.

Further reading

- Marouli, Eirini]; et al. (9 February 2017). "Rare and low-frequency coding variants alter human adult height". Nature. 542 (7640): 186–190. Bibcode:2017Natur.542..186M. doi:10.1038/nature21039. PMC 5302847. PMID 28146470.

External links

- CDC National Center for Health Statistics: Growth Charts of American Percentiles

- fao.org, Body Weights and Heights by Countries (given in percentiles)

- The Height Gap, Article discussing differences in height around the world

- Tallest in the World: Native Americans of the Great Plains in the Nineteenth Century

- European Heights in the Early eighteenth Century

- Spatial Convergence in Height in East-Central Europe, 1890–1910

- The Biological Standard of Living in Europe During the Last Two Millennia

- HEALTH AND NUTRITION IN THE PREINDUSTRIAL ERA: INSIGHTS FROM A MILLENNIUM OF AVERAGE HEIGHTS IN NORTHERN EUROPE

- Our World In Data – Human Height – Visualizations of how human height around the world has changed historically (by Max Roser). Charts for all countries, world maps, and links to more data sources.

- What Has Happened to the Quality of Life in the Advanced Industrialized Nations?

- A century of trends in adult human height, NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RISC), 25 July 2016, doi:10.7554/eLife.13410