Animal glue

Animal glue is an adhesive that is created by prolonged boiling of animal connective tissue in a process called rendering.[1] In addition to being used as an adhesive it is used for coating and sizing, in decorative composition ornaments, and as a clarifying agent.[1]

These protein colloid glues are formed through hydrolysis of the collagen from skins, bones, tendons, and other tissues, similar to gelatin. The word collagen itself derives from Greek κόλλα (kolla), meaning 'glue'. These proteins form a molecular bond with the glued object. Conventionally, keratin glues, while made from animal parts like horns and hooves, are not considered animal glues as they are not collagen glues.[2]

Stereotypically, the animal in question is a horse, and horses that are put down are often said to have been "sent to the glue factory". However, other animals are also used, including cattle,[3] rabbits and fish.[4]

History

Early uses

Animal glue has existed since ancient times, although its usage was not widespread. Glue deriving from horse tooth can be dated back nearly 6000 years, but no written records from these times can prove that they were fully or extensively used.[5]

The first known written procedures of making animal glue were written about 2000 BC. Between 1500 and 1000 BC, it was used for wood furnishings and mural paintings, found even on the caskets of Egyptian Pharaohs.[6] Evidence is in the form of stone carvings depicting glue preparation and use, primarily used for the pharaoh's tomb furniture.[7] Egyptian records tell that animal glue would be made by melting it over a fire and then applied with a brush.[8]

Ancient Greeks and Romans later used animal and fish glue to develop veneering and marquetry, the bonding of thin sections or layers of wood.[6] Animal glue, known as taurokolla (ταυρόκολλα) in Greek and gluten taurinum in Latin, were made from the skins of bulls in antiquity.[9] Broken pottery might also be repaired with the use of animal glues, filling the cracks to hide imperfections.[10]

About 906–618 BC, fish, ox horns and stag horns were used to produce adhesives and binders for pigments in China.[11] Animal glues were employed as binders in paint media during the Tang Dynasty. They were similarly used on the Terracotta Army figures.[12] Records indicate that one of the essential components of lampblack ink was proteinaceous glue. Ox glue and stag-horn glues bound particles of pigments together, acting as a preservative by forming a film over the surface as the ink dried.[9] The Chinese, such as Kao Gong Ji, also researched glue for medicinal purposes.[13]

Reemergence

The use of animal glue, as well as some other types of glues, largely vanished in Europe after the decline of the Western Roman Empire until the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, when wooden furniture started to surge as a major craft.[6] During the medieval ages, fish glue remained a source for painting and illuminating manuscripts.[14] Since the 16th century, hide glue has been used in the construction of violins.[7]

Native Americans would use hoof glue primarily as a binder and as a water-resistant coating by boiling it down from leftover animal parts and applying it to exposed surfaces. They occasionally used hide glue as paint to achieve patterns after applying pigments and tanning to hides.[15] Hoof glue would be used for purposes aside from hides, such as a hair preservative. The Assiniboins preferred longer hair, so they would plaster the strands with a mixture of red earth and hoof glue.[16] It would also be used to bind feathers and equipment together.[17]

Glue industries

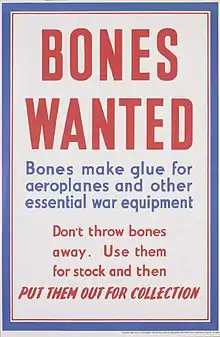

The first commercial glue factory opened in Holland circa 1700, manufacturing animal glue from hides.[6] The United States’ first glue factory opened in 1899, established by the Milwaukee Tanning Industry.[5] The L.D. Davis company thrived producing animal glue during the Great Depression after shifting its focus from stenciling, selling to local box makers and other users; L.D. Davis' animal glue formula for bookbinding remains in production.[18] During the 18th and 19th centuries, ranchers disposed of old animals – horses in particular – to glue factories. The advent of synthetic adhesives heralded the collapse of the animal glue industry.

Modern uses

Today, animal glues are sparsely industrialized, but still used for making and restoring violin family instruments, paintings, illuminated parchment manuscripts, and other artifacts.[9] Gelatin, a form of animal glue, is found in many contemporary products, such as gelatin desserts, marshmallows, pharmaceutical capsules,[19] and photographic film and is used to reinforce sinew wrappings, wood, leather, bark, and paper. Hide glue is also preferred by many luthiers over synthetic glues for its reversibility, creep-resistance and tendency to pull joints closed as it cures.

This adhesive is mostly used as glue, sizing, or varnish, although it is not as frequently used as other adhesives because it is water-soluble. Other aspects, such as difficulty of storage in a wet state, requirement for fresh raw materials (the animal skin cannot be rotten or grease-burned), make this product more difficult to find and use. Factories now produce other forms of adhesives, as the process for animal glue is complex and tricky to follow.[20] Animal glues will also darken with age and shrink as they dry, giving them the potential to harm wood, paper, or works of art. Too much handling and too many changes in temperature or humidity could cause further harm.[10] Some companies, such as those in Canada, still produce animal, hide and hoof glues from horses. Recently, animal glue has been replaced by other adhesives and plastics, but remains popular for restoration.

Types and uses

Animal glue was the most common woodworking glue for thousands of years until the advent of synthetic glues, such as polyvinyl acetate (PVA) and other resin glues, in the 20th century. Today it is used primarily in specialty applications, such as lutherie, pipe organ building, piano repairs, and antique restoration. Glass artists take advantage of hide glue's ability to bond with glass. As the glue hardens it shrinks, chipping the glass.

It has several advantages and disadvantages compared to other glues. The glue is applied hot, typically with a brush or spatula. Glue is kept hot in a glue pot, which may be an electric unit built for the purpose, a double boiler, or simply a saucepan or crock pot to provide a warm water bath for the container of glue. Most animal glues are soluble in water, useful for joints which may at some time need to be separated.[21] Alcohol is sometimes applied to such joints to dehydrate the glue, making it more brittle and easier to crack apart. Steam can also be used to soften glue and separate joints.

Specific types include hide glue, bone glue, fish glue, rabbit-skin glue.

Hide glue

Hide glue is made from animal hide (animal skin) and is often used in woodworking. It may be supplied as granules, flakes, or flat sheets, which have an indefinite shelf life if kept dry. It is dissolved in water, heated and applied warm, typically around 60 °C (140 °F). Warmer temperatures quickly destroy the strength of hide glue.[22] Commercial glue pots, simple water baths or double boilers may be used to keep the glue hot while in use. As hide glue cools, it gels quickly. At room temperature, prepared hide glue has the consistency of stiff gelatin, which is in fact a similar composition. Gelled hide glue does not have significant strength, so it is vital to apply the glue, fit the pieces, and hold them steady before the glue temperature drops much below 50 °C (120 °F). All glues have an open time, the amount of time the glue remains liquid and workable. Joining parts after the open time is expired results in a weak bond. Hide glue's open time is usually a minute or less. In practice, this often means having to heat the pieces to be glued, and gluing in a very warm room,[23] though these steps can be dispensed with if the glue and clamp operation can be carried out quickly.

Where hide glue is in occasional use, excess glue may be held in a freezer, to prevent spoilage from the growth of microorganisms. Hide glue has some gap filling properties,[24] although modern gap-filling adhesives, such as epoxy resin, are better in this regard.

Hide glue that is liquid at room temperature is also possible through the addition of urea. In stress tests performed by Mark Schofield of Fine Woodworking Magazine, "liquid hide glue" compared favourably to normal hide glue[25] in average strength of bond. "However, any liquid hide glue over six months old can be suspect because the urea eventually hydrolyzes the protein structure of the glue and weakens it – even though the product was 'protected' with various bactericides and fungicides during manufacture."[22]

Production

Animal hides are soaked in water to produce "stock." The stock is then treated with lime to break down the hides. The hides are then rinsed to remove the lime, any residue being neutralized with a weak acid solution. The hides are heated, in water, to a carefully controlled temperature around 70 °C (158 °F). The "glue liquor" is then drawn off, more water added, and the process repeated at increasing temperatures.

The glue liquor is then dried and chipped into pellets.[26]

Properties

The significant disadvantages of hide glue – its thermal limitations, short open time, and vulnerability to micro-organisms – are offset by several advantages. Hide glue joints are reversible and repairable. Recently glued joints will release easily with the application of heat and steam. Hide glue sticks to itself, so the repairer can apply new hide glue to the joint and reclamp it. In contrast, PVA glues do not adhere to themselves once they are cured, so a successful repair requires removal of the old glue first – which usually requires removing some of the material being glued.

Hide glue creates a somewhat brittle joint, so a strong shock will often cause a very clean break along the joint. In contrast, cleaving a joint glued with PVA will usually damage the surrounding material, creating an irregular break that is more difficult to repair. This brittleness is taken advantage of by instrument makers. For example, instruments in the violin family require periodic disassembly for repairs and maintenance. The top of a violin is easily removed by prying a palette knife between the top and ribs, and running it all around the joint. The brittleness allows the top to be removed, often without significant damage to the wood. Regluing the top only requires applying new hot hide glue to the joint. If the violin top were glued on with PVA glue, removing the top would require heat and steam to disassemble the joint (causing damage to the varnish), then wood would have to be removed from the joint to ensure no cured PVA glue was remaining before regluing the top.

Hide glue also functions as its own clamp. Once the glue begins to gel, it pulls the joint together. Violin makers may glue the center seams of top and back plates together using a rubbed joint rather than using clamps. This technique involves coating half of the joint with hot hide glue, and then rubbing the other half against the joint until the hide glue starts to gel, at which point the glue becomes tacky. At this point the plate is set aside without clamps, and the hide glue pulls the joint together as it hardens.

Hide glue regains its working properties after cooling if it is reheated. This property can be used when the glue's open time does not allow the joint to be glued normally. For example, a cello maker may not be able to glue and clamp a top to the instrument's ribs in the short one-minute open time available. Instead, the builder will lay a bead of glue along the ribs, and allow it to cool. The top is then clamped to the ribs. Moving a few inches at a time, the maker inserts a heated palette knife into the joint, heating the glue. When the glue is liquefied, the palette knife is removed, and the glue cools, creating a bond. A similar process can be used to glue veneers to a substrate. The veneer and/or the substrate is coated with hot hide glue. Once the glue is cold, the veneer is positioned on the substrate. A hot object such as a clothes iron is applied to the veneer, liquefying the underlying glue. When the iron is removed, the glue cools, bonding the veneer to the substrate.

Hide glue joints do not creep under loads. PVA glues create plastic joints, which will creep over time if heavy loads are applied to them.

Hide glue is supplied in many different gram strengths, each suited to specific applications. Instrument and cabinet builders will use a range from 120 to 200 gram strength. Some hide glues are sold without the gram strength specified. Experienced users avoid this glue as the glue may be too weak or strong for the expected application.

Rabbit-skin glue

Rabbit-skin glue is more flexible when dry than typical hide glues. It is used in the sizing or priming of oil painters' canvases. It also is used in bookbinding and as the adhesive component of some recipes for gesso and compo.

Fish glue

Fish glue is made from the bones or tissues of fish. Isinglass is made specifically from the swim bladders, and is collagen-based. Fish glues were used in Ancient Egypt and Classical Antiquity in the Mediterranean; they continued to be used in Europe in Late Antiquity and the Medieval period, and are still used in niche applications today. It is brittle when dried, so it has sometimes been mixed with plasticizers such as molasses and honey. It was used in art, woodworking, lutherie, and for gluing paper and bone.[27]

See also

Notes

- Animal Glue In Industry. New York, N.Y.: National Association of Glue Manufactures, Inc. 1951. p. 1. ASIN B000CQXC8Y.

- "adhesive | Definition, Types, Uses, Materials, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com.

- Animal Glue In Industry. New York, N.Y.: National Association of Glue Manufactures, Inc. 1951. p. 3. ASIN B000CQXC8Y.

- Mayer, Ralph (1991). The Artist's Handbook of Materials and Techniques. New York: Viking. p. 437. ISBN 0-670-83701-6.

Isinglass is a superlative grade of fish glue made by washing and drying the inner layers of the sounds (swimming bladders) of fish. The best grade, Russian isinglass, is obtained from the sturgeon.

- Feyh, Debi. "Glue". Nordic Needle. Archived from the original on 10 November 2011. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- "History of Adhesives". Autonopedia. Archived from the original on 26 March 2010. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- "History, Preparation, Use and Disassembly" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- Darrow, Floyd (1930). The story of an ancient art, from the earliest adhesives to vegetable glue. Perkins Glue Company.

- Petukhova, Tatyana (2000). A History of Fish Glue as an Artist's Material: Applications in Paper and Parchment Artifacts. The Book and Paper Group.

- Koob, Stephen (Spring 1998). "Obsolete Fill Materials Found on Ceramics". Journal of the American Institute for Conservation. 37 (1): 79–67. doi:10.2307/3179911. JSTOR 3179911.

- Edelman, Jonathan (2006). A Brief History of Tape.

- Yan, Hongtao; An, Jingjing; Zhou, Tie; Yin, Xia; Bo, Rong (July 2014). "Identification of proteinaceous binding media for the polychrome terracotta army of Emperor Qin Shihuang by MALDI-TOF-MS". Chinese Science Bulletin. 59 (21): 2574–2581. Bibcode:2014ChSBu..59.2574Y. doi:10.1007/s11434-014-0372-9. S2CID 96781019.

- "Animal Glue, Gelatin, Jelly Glue". Huakang Animal Glue. 20 February 2010. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- Laurie, A.P. (1910). The Materials of the Painter's Craft in Europe and Egypt from Earliest Times to the End of the XVIIth Century, with Some Account on their Preparation and Use. London & Edinburg: T. N. Foulis. (public domain fulltext)

- Harper, Patsy. "Natural Pigments: Women of the Fur Trade". Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- Sabin, Edwin (2010). Book of Indian Warriors. General LLC.

- Kaiser, Robert (1981). North American Sioux Indian Archery. Society of Archer-Antiquaries. Archived from the original on 2018-02-22. Retrieved 2011-12-09.

- "Animal Glue Growth with L.D. Davis 1936–1951". LD Davis Industries. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- "Animal Glue, Hot Melt Adhesive, Liquid Adhesive, Packaging Adhesive, Pur Glue, PVA Adhesives, Resin". L.D. Davis Industries.

- Edholm, Steven. Some Other Uses of Deer: Buckskin: The Ancient Art of Braintanning. pp. 255–272.

- Courtnall 1999, p. 63.

- Weisshaar 1988, p. 249.

- Courtnall 1999, p. 62.

- Ebnesajjad, Sina, ed. (2010). Handbook of Adhesives and Surface Preparation Technology. William Andrew. p. 160. ISBN 978-1437744613.

- Schofield, Mark. "How Strong is Your Glue?", Fine Woodworking Magazine, v. 192, 36–40. 2007

- "Glue Study Guide & Homework Help". eNotes.com. Archived from the original on 2011-05-18. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- Petukhova, Tatyana (2000). "A History of Fish Glue as an Artist's Material: Applications in Paper and Parchment Artifacts". cool.culturalheritage.org.

References

- Courtnall, Roy; Johnson, Chris (1999). The Art of Violin Making. London: Robert Hale. ISBN 0-7090-5876-4.

- Patrick Spielman. Gluing and Clamping: A Woodworker's Handbook. Sterling Publishing, 1986. ISBN 0-8069-6274-7

- Weisshaar, Hans; Shipman, Margaret (1988). Violin Restoration. Los Angeles: Weisshaar~Shipman. ISBN 0-9621861-0-4.

External links

- http://woodtreks.com/animal-protein-hide-glues-how-to-make-select-history/1549/ Video on hide glue, by Keith Cruickshank

- https://web.archive.org/web/20130522233935/http://www.oldbrownglue.com/articles.html Why Not Period Glue? - article by W. Patrick Edwards on hide glue

- http://wpatrickedwards.blogspot.com/2012/01/why-use-reversible-glue.html - Why Use Reversible Glue?