Venezuelan peasant insurrection of 1846

The Venezuelan peasant insurrection of 1846 was a popular and social rebellion that broke out in various agricultural areas of Venezuela in September 1846 and lasted until May 1847.

| Peasant insurrection of 1846 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Venezuelan civil wars | |||||||

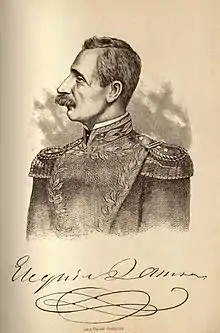

Carlos Soublette, president at the beginning of the war | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Conservative government | Federal rebels | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1,155 troops (492 line and 663 militiamen) and 2 schooners (Constitución and July 28) in September 1846[1] 4,096 troops, 3 schooners and 3 archers in December 1846[2] 5,208 troops in the West, 3,302 in the East, and 2,575 in the center in 1847[3] | - | ||||||

Background

Its main causes were the serious crisis that had been plaguing the country since 1842, the discontent of the rural population with the fiscal measures applied by the government of Carlos Soublette in 1843 and the incitement of the liberals led by Antonio Leocadio Guzmán, who launched harsh propaganda attacks against the Conservative government. These led to an insurrection in Villa de Cura under the command of Juan Silva in June 1844, another in September in Orituco under the command of Juan Celestino Centeno and the assault on the Calabozo prison in December 1845 by Juan and José Gabriel Rodríguez. All of them were quickly suppressed by the government; however, they were evidence of social discontent in the country.

In mid-1846, the economic and social crisis worsened, leading to political chaos due to the presidential campaigns in August of that year. The main competitors were José Tadeo Monagas, Antonio Leocadio Guzmán, Bartolomé Salom, José Félix and José Gregorio Monagas; the first had the support of the government; the second, that of the Liberal Party. Soublette increased the number of army recruits which was denounced by his opponents as a way to intimidate voters. The elections were finally held in great order; however, the chaos caused by the previous campaigns prevented a definitive and universally accepted result from being achieved.

Seeking to calm the situation, Santiago Mariño planned to meet with General José Antonio Páez, the most powerful man of the conservative regime, in Maracay and with the defeated candidate Antonio Leocadio Guzmán, who was residing in Caracas, to reach an agreement with the opposition. However, Guzmán left for the valleys of Aragua with a large number of supporters who were joined by new forces along the way. The government was alarmed at this and placed the troops on alert on 1 September. Because of this, the interview never took place.

War

On 2 September, Guzmán was in La Victoria, when Francisco José Rangel rose up at dawn near the town of Magdaleno, because the authorities had taken away his land and prevented him from voting in the recent elections. Acclaiming Guzmán, he attacked with his men the hacienda of Yuma, near Güigüe, property of the lawyer and Paecista politician Ángel Quintero, killing his butler, wounding some of its inhabitants and freeing the slaves. The government blamed Guzmán for what happened and later arrested him. While the rebel forces began to increase with the constant arrival of peons and slaves to their camps, they were eventually joined by Ezequiel Zamora, who was with Guzmán in La Victoria and became one of his main leaders in Villa de Cura.

Seeing that the peasants' rebellion was spiraling out of control, Soublette began to take steps to quell it. He named Páez the first chief of the army and sent him with 6,000 men to take control of the central-western region and José Tadeo Monagas as second chief in charge of controlling the Barloventeña and eastern region with 3,000 soldiers, he also requested a loan of 300,000 pesos to use in putting down the insurrection.

Consequences

Guerrillas remained scattered throughout the Venezuelan territory and the chaos allowed a sharp increase in common crime, with bands of outlaws attacking everyone without political background.[4] These forced to maintain an army of 813 line veterans, 972 militiamen and 212 municipal policemen as late as January 1848, when an amnesty had been given between June and August. The rebellion forced the conservatives to make an agreement with the liberals that brought Monagas to power, thus ending the hegemony of the former, called the Conservative Oligarchy, and beginning a new period called Monagato that lasted until 1858 and the March Revolution.[5]

References

- Irwin G., Domingo & Ingrid Micett (2008). Caudillos, militares y poder: una historia del pretorianismo en Venezuela. Caracas: Universidad Católica Andrés Bello, pp. 105. ISBN 9789802445615.

- Irwin G., 2008: 106. Archers used in Ciudad Bolívar for river transport, by that time the rebellion was unable to overthrow the government.

- Irwin G., 2008: 106.

- Irwin G., 2008: 108

- G, Domingo Irwin; Langue, Frédérique (2005). Militares y poder en Venezuela: ensayos históricos vinculados con las relaciones civiles y militares venezolanas (in Spanish). Universidad Catolica Andres. ISBN 978-980-244-399-4.