Childhood acquired brain injury

Childhood (or paediatric) acquired brain injury (ABI) is the term given to any injury to the brain that occurs during childhood but after birth and the immediate neonatal period. It excludes injuries sustained as a result of genetic or congenital disorder. It also excludes those resulting from birth traumas such as hypoxia or conditions such as foetal alcohol syndrome. It encompasses both traumatic and non-traumatic (or atraumatic) injuries.

| Childhood acquired brain injury | |

|---|---|

| |

| Brain | |

| Specialty | Paediatrics |

Pediatric acquired brain injury (PABI) is the number one cause of death and disability for children and young adults in the United States." and affects mostly children ages (6-10) and adolescent ages (11-17) around the world. The injury can be traumatic or non-traumatic in nature, and most patients never return to normal following the injury. There are many different symptoms such as amnesia, anhedonia, and apraxia. Currently there isn't a cure for the injury. PABI effects the family of the patient also, because the families of the patient will need to adapt to the new changes they will experience in their child. It is recommended that the families decide to gain as much information as they can about the injury and what to expect by going to different program events and meetings.

Traumatic injuries could include a blow to the head; gunshot; stabbing; crushing and excessive vibration / oscillation. This can be caused by shaking or sudden deceleration. Traumatic injuries might but do not necessarily have to involve an open wound or penetration of the skull or of the meninges - an 'open head' injury.

Non-traumatic injuries could include those caused by illnesses, such as tumours, encephalitis, meningitis and sinusitis. They could also be caused by infections such as septicaemia; events such as anoxia and hypoxia occasioned by strangulation or near drowning, lead toxicity, and substance misuse.

Symptoms and signs

Some symptoms that result from an acquired brain injury are amnesia, anhedonia, and apraxia.

Amnesia

"Childhood amnesia is the inability to remember one's own childhood." Researchers found that some everyday activities such as speaking, running, or playing a guitar, cannot be described or remembered.

Anhedonia

A child that is diagnosed with anhedonia would lack interest in some usual activities, such as hobbies, playing sports, or engaging with friends. It's very essential for a child to be able to enjoy fun childhood activities because it can help them build a social life, and easily interact with others. Not being able to do these things at a young age will only make it harder to adapt as the child gets older.

Apraxia

"Apraxia is the inability to execute learned purposeful movements, despite having the desire and the physical capacity to perform the movements." In this case, the child could have still have the memory of doing a usual activity such as riding a bike, but still not be able to accomplish the movement.

Prevalence and impacts

The prevalence of ABI amongst school-aged children in the UK is estimated to be in the region of 1 in 30,[1] based on admissions to A & E, although some professionals consider it to be much higher, as a child can be admitted to A & E with another more urgent injury, which is considered to be of overriding concern at the time.[1]

It can be tempting to assume that an injury acquired in childhood is likely to have a more positive long term outcome than one acquired during adulthood. It could be assumed that a child or adolescent could have a better chance of developing compensatory strategies whilst still at the stage where significant development and learning is taking place. If the injury is in any way significant this is often not the case.[2]

The inherent 'plasticity' of the brain can occasionally mean that areas damaged beyond healing can relocate their function to other undamaged areas (the so-called 'Kennard principle'[3]) and there are documented cases where this has indeed happened.[4] However, it is frequently the case that the functions associated with the damaged areas never fully develop and these deficits can present as significant disabilities or difficulties in later life.[5]

A significant proportion of the prior learning and the development of skills which has already taken place within an adult's brain can often be retained post injury. However, a brain at the earlier stages of development, if damaged, might never develop the capacity to learn those skills, leading to subsequent difficulties that could manifest themselves physically, socially, emotionally and educationally.[1]

Neurocognitive Problems

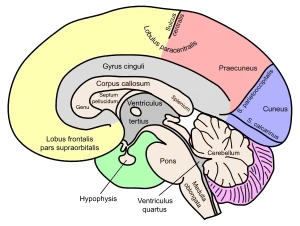

Delayed physiological responses post-TBI can lead to neurodegeneration in various parts of the brain in both chronic and severe cases in children. The parts of the brain that have been proven to be affected include: the hippocampus, amygdala, globus pallidus, thalamus, periventricular white matter, cerebellum, and brainstem.[6] As a result, this can lead to behavioral and cognitive problems in child development. Behavioral changes have been characterized as "externalizing" and "internalizing" problems.[7] Externalizing problems include different forms of aggression, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. The most common of these problems result from changes in attention and focus, such as ADHD.[8] Internalizing issues include psychiatric problems such as short-term and long-term depression, anxiety, personality disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Several variables can determine the outcome of behavioral problems in children post-TBI. For example, children that are already have behavioral issues before injury are more likely to develop long-term cognitive problems.[9] Another important factor is the severity of the injury, which can be a predictor of how long behavioral symptoms last and if they will increase over time.

Statistically about 54% to 63% of children develop novel psychiatric disorders about 24 months after severe TBI, and 10% to 21% after mild or moderate TBI, the most common of which is personality change due to TBI. The symptoms may last for 6 to 24 months on average.[10] Development of PTSD is common (68%) in the first few weeks post-injury with a decline in the course of 2 years. In cases of severe TBI about one third of children develop depressive disorder.[10] Children with severe TBI also have some effects on working memory, visual immediate memory, and more prominent consequences in intellectual functioning, executive functioning (including speed processing and attention), and verbal immediate and delayed memory. Some recovery is observed during the first 2 years post-injury.[11] Children with moderate TBI only show some decline in attention and problem solving, but larger effects in visual immediate memory.[11] The superior frontal lesions correlate with the type of outcome, but more importantly, subcortical network damage may affect the recovery due to the lesions in white matter tracts.[10] Children with severe TBI are at higher risk for not achieving developmentally appropriate gains and not catching up with peers at school due to the crucial stage of learning at which their neural networks are disrupted by the injury.[11]

Behavior

In children and adolescents that have an acquired brain injury, the cognitive and emotional difficulties that come about from their injury can negatively impact their level of participation in home, school and other social situations. This puts the patient at a disadvantage because they won't be nearly as social, or able to participate in a school setting as an ordinary child would. Involvement in social situations is important for the normal development of children as a means of gaining an understanding of how to effectively work together with others. Group work is a huge factor in academics today, and the child's ability to work within groups will be ineffective. Furthermore, young people with an acquired brain injury are often reported as having insufficient problem solving skills. This has the potential to hinder their performance in various academic and social settings further. It is important for rehabilitation programs to deal with these challenges specific to children who have not fully developed at the time of their injury.

Potential general effects

The effects can range from the relatively mild to the catastrophic but all will, to some degree, affect the child's ability to function within an educational and / or social setting. Educational attainment and quality of life indicators for young adult survivors of childhood acquired brain injury are significantly lower than those of an uninjured peer group.[12]

Because a child's brain is a 'work in progress', deficits caused by an injury sustained at one age might not become apparent until much later, as the damaged areas become relevant to the child's expected developmental milestones. This is known as the 'sleeper effect'[13] and where adults observing the child are unaware either of the injury itself or of the potential effects of an ABI, this can often lead to a misattribution of the failure to achieve academically and socially as 'laziness', 'teenage tantrums' and 'going off the rails'.

It is evident that damage to specific areas of the brain can result in whole areas of knowledge, skills and abilities being lost, sometimes irrevocably.[14] However, it is also often the case that although some cognitive abilities can be left intact, (including the ability to retrieve, process and manipulate information) and much prior learning can remain, a child can be prevented from developing academically and socially because of other, more functional, deficits.[1]

Potential social disadvantage

There are many ways in which a child with an ABI can become socially disadvantaged and alienated from his or her peers following an injury[15] and the following are only indicative of the problems that might follow reintroduction to their peer group.

A common sequela of brain injury is a much reduced ability to process information and therefore to respond to it promptly.[16] This can mean that a child is unable to keep up with the conversational flow of a group of friends and can be slower than the rest of the group to pick up on jokes and 'banter', leaving him/her feeling frustrated and left behind. However caring and well meaning, the friends can also find it difficult to accommodate this new slowness into their usual give and take, resulting in the affected child being alienated and left out.

Another effect often seen as a result of damage to the vulnerable frontal lobes of a child's brain is 'disinhibition'[15] or a reduced ability to inhibit an impulse to say or do something long enough to calculate whether it's the correct or appropriate thing to say or do. Research shows that adolescence is the time when the frontal lobe areas of the brain - the areas that govern the ability to manage one's behaviours - develop enough to allow a child to begin to 'grow up' and start to inhibit their initial impulses.[17]

Disinhibition can lead to a child saying apparently hurtful or aggressive things to peers, leading to antagonism and embarrassment. It can also be the case that because of this, a child with an ABI will be less able to inhibit their responses to other provocations, such as adult authority, resulting in apparent 'bad' behaviour, leading their friends (or their friends' parents) to view them as unsuitable companions. Disinhibition can also lead to sexually harmful behaviour, particularly when coupled with a lowered sense of risk and danger and a child with a brain injury can often become vulnerable to exploitation by peers or by strangers.

A reduced ability to access and to process language and therefore to 'word find' appropriately can result in an increased inclination to use a more readily accessible word - such as a swear word or a more aggressive word - and this can obviously alienate and concern friends, who could interpret this as anger or aggression.

Potential emotional effects

Everything we are, everything we are able to do and everything we feel is governed by the functioning of our brain. What we grow to see as fundamentally 'me' is a product of our brain and the experiences that have shaped it.

When a child experiences a brain injury, its effects could alter his or her academic abilities, likes and dislikes, friendship groups, talents and skills, plans for the future, relationships with parents and siblings, physical prowess - everything that made the child the person they knew themselves to be.

The dissonance between the self-image pre injury and the new one post injury can be experienced as a real trauma,[18] as the child tries to come to terms with the new 'me', the 'death' of the old one and the limitations possibly imposed by the effects of the injury.

The loss of academic or sporting status, the indifference or antagonism of their peer group, the curtailing of their developing independence because of understandable parental worry, could all be experienced by a brain injured child or adolescent as almost a bereavement.

It is not unusual for a brain injured child to experience feelings of worthlessness, depression and loss.[13]

Family relationships could also suffer as a result of the injury, as parents struggle to come to terms with the same feelings of bereavement of their plans and hopes for their child, for their family unit and for the life they lived together before the injury. Siblings also could find it hard to come to terms with the loss of the brother or sister they knew and loved and with the amount of time, attention and emotional energy their parents have expended on the injured child.

Potential misattribution of effects

A childhood acquired brain injury can have a huge variety of effects on the child, at different times during the development of their brain function. Depending on how well informed another person is about the injury and about the nature of brain development, it can often be easy to ascribe aspects of a child's behaviour (or 'presentation') to the wrong underlying reason. It is, for example, common for parents and teachers to misread the effects of a cognitive impairment for a physical issue and a physical problem for a 'behavioural' one.

An example of this could be a child who has great difficulty in 'initiating' a task or in sequencing elements of a simple task. When the child fails to respond to what appears to be a straightforward instruction, for example 'put away your art work then go over there and get changed for PE', and is found still to be sitting at his desk five minutes later, the teacher might reach the conclusion that he is lazy or defiant.

Similarly, a child who has a visual impairment as a result of her injury could be mistaken for being clumsy and uncoordinated or just thoughtless, when she knocks over the milk jug or for being scatterbrained and inattentive when she neglects to complete the math problems written on the right hand side of the board.

Pathophysiology

The pediatric brain undergoes dramatic changes and significant pruning of neural networks throughout development. Whereby the areas for primary senses and motor skills are mostly developed by age 4, other areas, like the frontal cortices involved in higher level reasoning, decision-making, emotion, and impulsivity continue to develop well into the late teens to early 20s. Therefore, the patient's age and brain developmental state influence what neuronal systems become most affected post-injury.[19] Key structural features of the pediatric brain make the brain tissue more susceptible to the mechanical injury during TBI than the adult brain: a larger water content in the brain tissue and reduced myelination results in diminished shear resistance after injury. It has also been shown that more immature brains have an enlarged extracellular space volume and a decreased expression of glial aquaporin 4 leading to an increased incidence of brain swelling after TBI.[20] Along with a delayed decrease in cerebral blood flow, these unique features of the developing brain can mediate further secondary damage, through hypoxia, excitotoxicity, free radical damage, and neuroinflammation after the primary injury.[19][20] Even properties of these secondary events differ between the developing brain and the adult brain: (1) in the developing brain, the overexpression and activation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDA-R) leads to an increased calcium influx and an increased capacity for excitoxicity when compared to the adult brain and (2) the developing brain has lower glutathione peroxidase activity and a decreased ability to maintain stores of glutathione peroxidase, therefore the developing brain is more vulnerable to oxidative stress than the adult brain.[20] Damage to the developing brain, by any of the above mechanisms, can disturb neuronal maturation, leading to neuronal loss, axonal destruction, and demyelination.[21]

Training

There are many different ways to "train" the children diagnosed with Pediatric Brain Injury. The training mainly tests their brain, to see exactly what's wrong with the patient, and what areas need to be focused on for improvement.

AIM Program

"AIM is a 10-week, computerized treatment program that incorporates goal setting, the use of metacognitive strategies, and computer-based exercises designed to improve various aspects of attention."[22] "During the initial meeting with the child, the computer program leads the clinician through an intake procedure that assists in identifying the nature and severity of the child's attention difficulties and then facilitates the selection of attention training tasks and metacognitive strategies tailored to the needs of the child." The clinician's role is to select the specific, presenting mental areas that are impaired, as well as to modify the tasks and strategies in response to improvements of the patients' overtime.[22] This is a helpful way to figure out what problems the child/adolescent is facing, while also helping them to gradually improve their injury.

Parent's Assistance for Patients

"Investigators have established that interventions for pediatric BI should target the family because changes in one family member will affect the entire family system."[23] "During rehabilitation, caregivers often receive skills training to improve their ability to care for their child after their brain injury.[23] Family realignment and adjusting the child's environment are two major ways parents can make the distresses of the injury easier on their child. Some beneficial ways parents can realign their household are applying consequences to minimize problem behaviors, increasing the amount of positive communication between parents and child with injury, and establishing positive routines that will instill meaning into the child's day-to-day life.[23]

References

- Wicks, B; Walker, S (2005). Educating Children with Acquired Brain Injury. Abingdon: David Fulton.

- Anderson, V; Spencer-Smith, M; Wood, A (January 2011). "Do children really recover better? Neurobehavioural plasticity after early brain insult". Brain. 134 (1): 2197–2215. doi:10.1093/brain/awr103. PMID 21784775.

- Anderson V, et al. (August 2011). "Neurobehavioural Recovery From Early Brain Insult—Early Plasticity or Early Vulnerability: What is the Evidence?". Brain. 134 (8): 2197–2221. doi:10.1093/brain/awr103. PMID 21784775.

- Bach y Rita, P (1990). "Brain plasticity as a basis for recovery of function in humans". Neuropsychologia. 28 (6): 547–554. doi:10.1016/0028-3932(90)90033-k. PMID 2395525. S2CID 45957183.

- Giza, C (2006). "Lasting Effects of Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury". Indian Journal of Neurotrauma. 3 (1): 19–26. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.320.5102. doi:10.1016/s0973-0508(06)80005-5.

- Keightley, Michelle (March 2014). "Is there evidence for neurodegenerative change following Traumatic Brain Injury in children and youth? A scoping review". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 8 (139): 139. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00139. PMC 3958726. PMID 24678292.

- Li, Liu (January 2013). "The effect of pediatric traumatic brain injury on behavioral outcomes: a systematic review". Dev Med Child Neurol. 55 (1): 37–45. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04414.x. PMC 3593091. PMID 22998525.

- Bloom, DR (May 2001). "Lifetime and novel psychiatric disorders after pediatric traumatic brain injury". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 40 (5): 572–579. doi:10.1097/00004583-200105000-00017. PMID 11349702.

- Yeates, KO (June 2005). "Long-term attention problems in children with traumatic brain injury". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 44 (6): 574–584. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000159947.50523.64. PMID 15908840.

- Max JE (January 2014). "Neuropsychiatry of Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury". Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 37 (1): 125–140. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2013.11.003. PMC 3977029. PMID 24529428.

- Babikian T, Asarnow R (May 2009). "Neurocognitive outcomes and recovery after pediatric TBI: meta-analytic review of the literature". Neuropsychology. 23 (3): 283–96. doi:10.1037/a0015268. PMC 4064005. PMID 19413443.

- Anderson V, et al. (2009). "Educational, Vocational, Psychosocial, and Quality-of-Life Outcomes for Adult Survivors of Childhood Traumatic Brain Injury". Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 24 (5): 303–312. doi:10.1097/htr.0b013e3181ada830. PMID 19858964. S2CID 12030935.

- Baldwin T, et al. (2006). "Cognitive Deficits". In Appleton R, Baldwin T (eds.). Management of Brain Injured Children. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 130–167.

- Savage, RC; Wolcott, GF (1995). "Educational Issues for Students with Brain Injuries". In Savage, R; Wolcott, GF (eds.). An Educator's Manual - what educators need to know about students with brain injury (3rd ed.). Washington DC: Brain Injury Association Inc. pp. 1–10.

- Ashworth, J (2013). "How can children with an ABI achieve their potential?". Journal of Social Care and Neurodisability. 4 (2): 20–23.

- Middleton, J (2001). "Brain Injury in Children and Adolescents". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 7 (1): 257–265. doi:10.1192/apt.7.4.257.

- Sowell E, et al. (1999). "In vivo evidence for post-adolescent brain maturation in frontal and striatal regions". Nature Neuroscience. 2 (1): 859–861. doi:10.1038/13154. PMID 10491602. S2CID 5786954.

- American Psychiatric Association (2000). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV (TR) (4th ed.). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Toledo, E; Lebel, A; Becerra, L; Minster, A; Linnman, C; Maleki, N; Dodick, DW; Borsook, D (July 2012). "The young brain and concussion: imaging as a biomarker for diagnosis and prognosis". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 36 (6): 1510–31. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.03.007. PMC 3372677. PMID 22476089.

- Bauer, R; Fritz, H (October 2004). "Pathophysiology of traumatic injury in the developing brain: an introduction and short update". Experimental and Toxicologic Pathology. 56 (1–2): 65–73. doi:10.1016/j.etp.2004.04.002. PMID 15581277.

- Keightley, ML; Sinopoli, KJ; Davis, KD; Mikulis, DJ; Wennberg, R; Tartaglia, MC; Chen, JK; Tator, CH (2014). "Is there evidence for neurodegenerative change following traumatic brain injury in children and youth? A scoping review". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 8: 139. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00139. PMC 3958726. PMID 24678292.

- Sohlberg MM, Harn B, MacPherson H, Wade SL (September 2014). "A Pilot Study Evaluating Attention And Strategy Training Following Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury". Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology. 2 (3). doi:10.1037/cpp0000072.

- Cole, Wesley; Paulos, Stephanie (2009). "A Review of Family Intervention Guidelines for Pediatric Acquired Brain Injuries". Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 15 (2): 159–66. doi:10.1002/ddrr.58. PMID 19489087.