Pedro Sánchez

Pedro Sánchez Pérez-Castejón (Spanish: [ˈpeðɾo ˈsantʃeθ ˈpeɾeθ kasteˈxon]; born 29 February 1972) is a Spanish politician who has been Prime Minister of Spain since June 2018.[1][2] He has also been Secretary-General of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) since June 2017, having previously held that office from 2014 to 2016. Moreover, Sánchez is the current President of the Socialist International, having been elected to that position in November 2022.

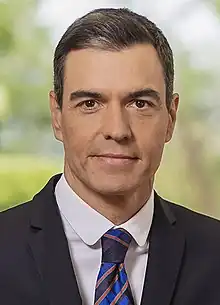

Pedro Sánchez | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 2023 | |

| Prime Minister of Spain | |

| Assumed office 2 June 2018 | |

| Monarch | Felipe VI |

| Deputy | Nadia Calviño Yolanda Díaz Teresa Ribera |

| Preceded by | Mariano Rajoy |

| Secretary-General of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party | |

| Assumed office 17 June 2017 | |

| President | Cristina Narbona |

| Deputy | Adriana Lastra María Jesús Montero |

| Preceded by | Caretaker committee |

| In office 26 July 2014 – 1 October 2016 | |

| President | Micaela Navarro |

| Preceded by | Alfredo Pérez Rubalcaba |

| Succeeded by | Caretaker committee |

| President of the Socialist International | |

| Assumed office 25 November 2022 | |

| Preceded by | George Papandreou |

| Leader of the Opposition | |

| In office 18 June 2017 – 2 June 2018 | |

| Prime Minister | Mariano Rajoy |

| Preceded by | Vacant |

| Succeeded by | Pablo Casado |

| In office 26 July 2014 – 1 October 2016 | |

| Prime Minister | Mariano Rajoy |

| Preceded by | Alfredo Pérez Rubalcaba |

| Succeeded by | Vacant |

| Member of the Congress of Deputies | |

| Assumed office 21 May 2019 | |

| Constituency | Madrid |

| In office 10 January 2013 – 29 October 2016 | |

| Constituency | Madrid |

| In office 15 September 2009 – 27 September 2011 | |

| Constituency | Madrid |

| Member of the Madrid City Council | |

| In office 18 May 2004 – 15 September 2009 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Pedro Sánchez Pérez-Castejón 29 February 1972 Madrid, Spain |

| Political party | Spanish Socialist Workers' Party |

| Spouse |

Begoña Gómez (m. 2006) |

| Children | 2 |

| Residence | Palace of Moncloa |

| Education | Complutense University of Madrid (Lic.) Université libre de Bruxelles IESE Business School Camilo José Cela University (PhD) |

| Signature |  |

Sánchez began his political career in 2004 as a city councillor in Madrid, before being elected to the Congress of Deputies in 2009. In 2014, he was elected Secretary-General of the PSOE, becoming Leader of the Opposition. He led the party through the inconclusive 2015 and 2016 general elections, but resigned as Secretary-General shortly after the latter, following public disagreements with the party's executive. He was subsequently re-elected in a leadership election eight months later, defeating Susana Díaz and Patxi López.

On 1 June 2018, the PSOE called a vote of no confidence in Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy, successfully passing the motion after winning the support of Unidas Podemos, as well as various regionalist and nationalist parties. Sánchez was subsequently sworn in as Prime Minister by King Felipe VI the following day. He went on to lead the PSOE to gain 38 seats in the April 2019 general election, the PSOE's first national victory since 2008, although they fell short of a majority. After talks to form a government failed, Sánchez again won the most votes at the November 2019 general election; further, in January 2020 he formed a minority coalition government with Unidas Podemos, the first national coalition government since the country's return to democracy.

Early life

Pedro Sánchez Pérez-Castejón was born in 1972 in Madrid to a well-off family,[3][4] son to Pedro Sánchez Fernández and Magdalena Pérez-Castejón.[3] His father was a public administrator long employed at the Ministry of Culture's Instituto Nacional de las Artes Escénicas y de la Música (lit. 'National Institute of the Performing Arts and Music'). He later became the owner of an industrial packing company. His mother worked as a civil servant in the social security system (later becoming a lawyer, graduating with her son at the same university).[3][5] Raised in the Tetuán district,[6] he studied at the Colegio Santa Cristina, also located in the district.[7] According to Sánchez himself, he frequented breakdancing circles in AZCA when he was a teenager.[8][9] He moved from the Colegio Santa Cristina to the Instituto Ramiro de Maeztu,[7] a public high school where he played basketball in the Estudiantes youth system, with links to the high school, reaching the U-21 team.[10]

In 1990, Sánchez went to study economics and business sciences. In 1993, he joined the PSOE after the victory of Felipe González in the elections that year.[11] Sánchez earned a licentiate degree from the Real Colegio Universitario María Cristina, attached to the Complutense University of Madrid, in 1995.[12] Following his graduation he worked in New York for a consulting firm.[13]

In 1998, before entering a career in local and national politics, Sánchez started to work in Brussels in the PSOE's delegation to the European Parliament as assistant to MEP Bárbara Dührkop.[14] He also worked in the staff of the United Nations high representative in Bosnia, Carlos Westendorp.[15] He earned a degree in Politics and Economics in 1998 after graduating from the Université libre de Bruxelles.

He earned a degree of business leadership from IESE Business School in the University of Navarra, a private university and apostolate of the Opus Dei.[16] Sánchez obtained a diploma in Advanced Studies in EU Monetary Integration from the Instituto Ortega y Gasset in 2002.[17]

Political career

Early local and national career

In 2003, Sánchez stood in the Madrid City Council election on the PSOE list headed by Trinidad Jiménez. He was 23rd on the proportional representation list, but the PSOE only won 21 seats. Sánchez did not become a city councillor until a year later, when two socialist councillors resigned. He quickly became one of the fundamental components of opposition leader Trinidad Jiménez's team.[18] Between 18 May 2004 – 15 September 2009, he was one of the 57 members of the City Council of Madrid, representing PSOE in the city of Madrid. At the same time, he went to help the PSdG (PSOE's affiliated party in Galicia) contest the 2005 Galician regional election,[10] in which PSdG won eight seats, allowing Emilio Pérez Touriño to become president of Galicia. In 2007, he was part of the Miguel Sebastián campaign for Madrid's premiership. In parallel to his seat at the city council, Sánchez started to work as instructor at the Universidad Camilo José Cela (UCJC) in 2008, lecturing about Economic Structure and History of Economic Thought.[17]

Sánchez was elected to the Congress of Deputies for Madrid, replacing Pedro Solbes, Minister of Economy and Finance in the José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero cabinet, after Solbes retired from politics in 2009.

In the general election of 2011, which saw a heavy defeat for the Socialists, PSOE placed Sánchez 11th on the Proportional Representation list, while only electing 10 deputies. Having thus failed to win a seat, he focused on preparing his Doctorate in Economics at the UCJC, earning the PhD in November 2012 by writing a dissertation titled Innovaciones de la diplomacia económica española: Análisis del sector público (2000–2012) (English translation: Innovations of Spanish Economic Diplomacy: Analysis of the Public Sector (2000–2012)) supervised by María Isabel Cepeda González.[17] In 2018 Sánchez was accused by the Spanish daily ABC of plagiarism.[19] In order to refute the plagiarism allegations, Sánchez published his full thesis online.[20][21]

In January 2013, Sánchez returned to Congress, replacing Cristina Narbona, who left her seat to enter the Nuclear Safety Council. In December 2013, after numerous Socialist leaders such as Elena Valenciano, Trinidad Jiménez, Miguel Sebastián, and José Blanco López attended his new book release, his name began to be discussed as a prospective candidate for the party leadership.

Sánchez officially launched his bid to party leader on 12 June 2014. He was elected as the Secretary-General on 13 July, after winning 49% of votes against his opponents Eduardo Madina and José Antonio Pérez Tapias (member of the Socialist Left platform).[10][22] He was confirmed as Secretary-General after an Extraordinary Congress of the PSOE was held on 26–27 July that ratified the electoral result.[10]

Leading the opposition

Representing a platform based on political regeneration, Sánchez demanded constitutional reforms establishing federalism as the form of administrative organization of Spain to ensure that Catalonia would remain within the country; a new progressive fiscal policy; extending the welfare state to all citizens; joining labour unions again to strengthen economic recovery; and regaining the confidence of former Socialist voters disenchanted by the measures taken by Zapatero during his term as Prime Minister amid an economic crisis. He also opposed the grand coalition model supported by the former Prime Minister and PSOE leader Felipe González, who lobbied in favour of the German system in case of political instability. Sánchez asked his European party caucus not to vote for the consensus candidate Jean-Claude Juncker of the European People's Party.[23]

Upon taking office as PSOE's Secretary-General, Sánchez faced a political crisis after the formation of a new party, Podemos. Approximately 25% of all PSOE supporters switched their loyalties to Podemos.[24][25] Sánchez's political agenda included reforming the constitution, establishing a federal model in Spain to replace the current devolution model,[26] and further secularization of Spain's education system, including the removal of religion-affiliated public and private schools.[27] He named César Luena as his second-in-command. On 21 June 2015, Sánchez was officially announced as the PSOE premiership candidate for the December 2015 general election. His party earned 90 seats, being second to rivals of Partido Popular (PP), who won the election with 123 representatives out of a parliament formed by 350. Since PP's leader did not stand officially for the premiership, following this Sánchez was requested by the King to form a coalition, but he was unable to obtain the support of a majority of representatives. This led to a further general election in June 2016, where he stood again as PSOE's prospective candidate to prime minister. The party won only 85 seats in the general election.

Removal and political comeback

Amid deep inner strife within the party started by September 2016 (the 2016 PSOE crisis), Sánchez lost support from the PSOE's federal committee in a key vote and was forced to resign as Secretary-General on 1 October 2016.[28] His defeated proposal (107 in favour versus 132 against) was that of celebrate a snap PSOE primary election in October 2016 and a party congress in November.[28]

.jpg.webp)

In order to avoid obeying the directive of the PSOE's interim leadership to facilitate Mariano Rajoy's investiture as Prime Minister by means of an abstention and thus "betraying his word", Sánchez also renounced to his seat at the Congress of Deputies in October 2016, and started to prepare for a new candidacy to the leadership of the party in the upcoming primary election.[29][30] Besides the renunciation of Sánchez, 15 PSOE MPs would break party discipline by voting against Rajoy,[n. 1] yet as Rajoy only needed the abstention from 11 PSOE MPs (out of 84), the latter was invested as Prime Minister.[31]

After resigning as Secretary-General of the party and to prepare for his bid to party leadership, Sánchez made a tour aboard his car visiting base members in different parts of Spain.[32][33] On 21 May 2017, Sánchez was re-elected Secretary-General for the second time with 50.2% of the votes, over his competitors Susana Díaz (39.94%) and Patxi López (9.85%).[34]

Sánchez opposed the Catalan independence referendum and supported the Rajoy government's decision to dismiss the Catalan government and impose direct rule on Catalonia in October 2017.[35][36]

In May 2018, after verdicts were announced in the Gürtel trial, PSOE filed a successful no-confidence motion against Mariano Rajoy.[37] Per the Constitution, Spanish votes of no confidence are constructive; those bringing the motion must propose a replacement candidate for Prime Minister. Accordingly, the PSOE proposed Sánchez (who was not a member of the Congress of Deputies at the time) as Rajoy's replacement. With the passage of the no-confidence motion, Sánchez was automatically deemed to have the confidence of the Congress of Deputies and thus ascended as Prime Minister on 1 June 2018.

Premiership (2018–present)

.jpg.webp)

Sánchez was sworn in as Prime Minister by King Felipe VI on 2 June.[38] Sánchez said he planned to form a government that would eventually dissolve the Cortes Generales and call for a general election, but he did not specify when he would do it while also saying that before calling for an election he intended take a series of measures like increasing unemployment benefits and proposing a law of equal pay between the sexes.[39][40] However, he also said he would uphold the 2018 budget approved by the Rajoy government, a condition the Basque Nationalist Party imposed to vote for the motion of no-confidence.[41]

Spanish media noted that while Sánchez was swearing his oath of office on the Spanish Constitution, no Bible or crucifix were on display for the first time in modern Spanish history, due to Sánchez's atheism.[42] After being sworn in, Sánchez announced that he would only propose measures that had considerable parliamentary support, and re-affirmed the government's compliance with the EU deficit requirements.[43]

Foreign policy

Sánchez has taken a more active role in the international sphere, especially in the European Union, saying that "Spain has to claim its role" and declaring himself "a militant pro-European".[44] On 16 January 2019, in a speech before the European Parliament, he said that the EU should be protected and turned into a global actor, and that a more social Europe is needed, with a strong monetary union.[45] He stated in a speech in March 2019 adding that the enemies of Europe are inside of the European Union.[46][47] In his second government, he continued strengthening the pro-European profile of its ministers, appointing José Luis Escrivá, the then chair of the Independent Authority for Fiscal Responsibility and former chair of the EU Independent Fiscal Institutions Network, as minister for social security.[48] In June 2020, the Sánchez government proposed deputy prime minister and economy minister, Nadia Calviño, to be the next chair of the Eurogroup.[49]

.jpg.webp)

In September 2018, during his first term in office as Prime Minister, Defense Minister Margarita Robles cancelled sales of laser-guided bombs to Saudi Arabia over concerns relating to the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen. Overruling Robles, Sánchez ordered the sale to proceed[50] because he had promised President of Andalusia Susana Díaz to help protect jobs in the shipyards of the Bay of Cádiz, highly dependent on the €1.813 billion contract with Saudi Arabia to deliver five corvettes.[51][52] In response to the killing of Saudi dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi in October 2018, Sánchez defended the decision to continue arms sales to Saudi Arabia and insisted on his government's "responsibility" to protect jobs in the arms industry.[53][54]

.jpg.webp)

Following the fall of Kabul and the subsequent de facto creation of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, the Prime Minister offered Spain as a hub for Afghans who collaborated with the European Union, which would later be settled in various countries.[55] The Spanish government created a temporary refugee camp in the air base of Torrejón de Ardoz, which was later visited by officials from the European Union, including president of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen and president of the European Council Charles Michel. Von der Leyen praised Sánchez government's initiative, stating that the actions of Spain represents "a good example of the European soul at its best".[56] US President Joe Biden spoke with Sánchez to allow the use of the military bases of Rota and Morón to temporarily accommodate Afghan refugees, while praising "Spain's leadership in seeking international support for Afghan women and girls".[57][58]

On August 2022, during his state visit to Serbia as part of his overall visits to Balkan countries, Sánchez reaffirmed Spain's non-recognition of the independence of Kosovo.[59]

Domestic policy

On 18 June 2018, Sánchez' government announced its intention to remove the remains of former dictator Francisco Franco from the Valley of the Fallen.[60] On 24 August 2018, Sánchez's cabinet approved a decree that modifies two aspects of the 2007 Historical Memory Law to allow the exhumation of Franco's remains from the Valley of the Fallen. After a year of legal battles with Franco's descendants, the exhumation took place on 24 October 2019, and Franco was reburied at Mingorrubio Cemetery in El Pardo with his wife Carmen Polo.[61]

After the sentence in 2019 trial of Catalonia independence leaders Sánchez confirmed his support of the sentence, and denied the possibility of any indulgence, proclaiming that the sentence should be served by the convicts in its entirety,[62] in spite of that two years later Sánchez granted indulgence to all convicts.[63] Shortly after granting the indulgence, Sánchez stressed that despite the indulgence, there would never be a referendum for the independence of Catalonia,[64] in response he was mocked by Gabriel Rufian and other Catalan politicians, who reminded him that two years prior he had made the same claim with regards to granting indulgences, and insinuated that it is just a matter of time before Sánchez will break his latest claims.[64]

Under Sánchez's leadership, the Cortes Generales approved a total central government budget of 196 billion euros – the biggest budget in the country's history – in 2021, after he had won the support of the Catalan pro-independence Republican Left of Catalonia.[65]

COVID-19 pandemic

On 13 March 2020, Sánchez announced a declaration of the state of alarm in the nation for a period of 15 days, to become effective the following day after the approval of the Council of Ministers, becoming the second time in democratic history and the first time with this magnitude.[66] The following day imposed a nationwide lockdown, banning all trips that were not force majeure and announced it may intervene in companies to guarantee supplies.[67][68] On July 14, 2021, the Constitutional Court of Spain, acting upon the 2020 appeal by Vox, sentenced by a narrow majority (6 votes in support vs. 5 votes against) that the state of alarm was unconstitutional in the part of suppressing the freedom of movement established by the Article 19 of the Constitution of Spain.[69]

2023 snap election

After the negative outcome of the 2023 regional and local elections, Sanchez announced a snap general election for 23 July. In a speech, Sanchez stated that it was important to listen to the will of the people, but stressed the need to persevere with post-Covid economic recovery measures implemented by his government.[70]

After Alberto Núñez Feijóo's failed attempt to form a government, the king asked Sánchez to try to form a government.[71]

Ideology

Sánchez ran in the 2014 PSOE primary election under what has been described as a centrist and social liberal profile, later switching to the left in his successful 2017 bid to return to the PSOE leadership in which he stood for a refoundation of social democracy, in order to transition to a "post-capitalist society", ending "neoliberal capitalism".[72][73][74][75] A key personal idea posed in his 2019 Manual de Resistencia book is the indissoluble link between "social democracy" and "Europe".[76]

Sánchez is a strong opponent of prostitution, and supports its abolition.[77]

Personal life

Sánchez married María Begoña Gómez Fernández[78] in 2006 and they have two children. The civil wedding was officiated by Trinidad Jiménez.

Aside from Spanish, Sánchez speaks fluent English and French.[79][18][80] He is the first Spanish prime minister fluent in English while in office (former PM José María Aznar learned English after leaving office). Foreign languages were not widely taught in Spanish schools until the mid-1970s, and former Prime Ministers were known for struggling with them.[81][82]

Electoral history

| Election | List | Constituency | List position | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 Madrid City Council election | PSOE | – | 24th (out of 55) | Not elected[lower-alpha 1] |

| 2007 Madrid City Council election | PSOE | – | 15th (out of 57) | Elected |

| 2008 Spanish general election | PSOE | Madrid | 21st (out of 35) | Not elected[lower-alpha 2] |

| 2011 Spanish general election | PSOE | Madrid | 11th (out of 36) | Not elected[lower-alpha 3] |

| 2015 Spanish general election | PSOE | Madrid | 1st (out of 36) | Elected |

| 2016 Spanish general election | PSOE | Madrid | 1st (out of 36) | Elected |

| April 2019 Spanish general election | PSOE | Madrid | 1st (out of 37) | Elected |

| November 2019 Spanish general election | PSOE | Madrid | 1st (out of 37) | Elected |

| ||||

Distinctions

- Medal of Salvador Allende (28 August 2018).[84]

- Grand Collar of the Order of the Condor of the Andes (29 August 2018).[85]

- Grand Cross of the Order of the Sun of Peru (27 February 2019).[86]

- Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic (16 November 2021).[87]

Notable published works

- Ocaña Orbis, Carlos y Sánchez Pérez-Castejón, Pedro (2013): La nueva diplomacia económica española. Madrid: Delta. ISBN 9788415581512.[88]

- Sánchez Pérez-Castejón, Pedro (2019): Manual de resistencia. Madrid: Península. ISBN 9788499427959.[89]

Controversial authorship

- In 2018 a newspaper revealed that his book La nueva diplomacia económica española includes the plagiarism of six other people's texts.[19] The suspicion was extended to his doctoral thesis, whose authorship was questioned.[90]

- Regarding Manual de resistencia, Sánchez is given as the author, but the falsity of this claim is deduced from the words of Sánchez himself, who states in the prologue that "This book is the result of long hours of conversation with Irene Lozano, writer, thinker, politician and friend. She gave a literary form to the recordings, giving me a decisive help".[91] The mentioned writer, for her part, affirmed that "I made the book, but the author is the prime minister".[92]

Notes

- Meritxell Batet, Marc Lamuà, Manuel Cruz, María Mercè Perea, Lídia Guinart, Joan Ruiz, José Zaragoza, Margarita Robles, Zaida Cantera, Odón Elorza, Pere Joan Pons, Sofía Hernanz, María del Rocío de Frutos, Susana Sumelzo and María Luz Martínez.[31]

References

- "Relación cronológica de los presidentes del Consejo de Ministros y del Gobierno". lamoncloa.gob.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- "Real Decreto 354/2018, de 1 de junio, por el que se nombra Presidente del Gobierno a don Pedro Sánchez Pérez-Castejón" (PDF). Boletín Oficial del Estado (in Spanish). Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado (134): 57657. 2 June 2018. ISSN 0212-033X.

- Hernández, Nuria (22 March 2020). "Así es la familia más cercana de Pedro Sánchez". Vanity Fair.

- Pedro Sánchez, la vida familiar del político al que han apodado 'míster PSOE 2014' Published by Vanitatis, 23 June 2014, accessed 26 June 2014

- Peláez, Raquel (10 September 2018). "¿Por qué Pedro Sánchez jamás habla de su colegio pero siempre presume de instituto?". Vanity Fair.

- Ruiz Valdivia, Antonio (3 March 2016). "34 cosas que no sabías de Pedro Sánchez". The Huffington Post.

- Taulés, Silvia (10 November 2019). "Así eran de niños los candidatos a Moncloa: baloncesto, guitarra, natación, Maquiavelo..." Vanitatis – via El Confidencial.

- "El joven Pedro Sánchez, bailarín de 'break dance', "ligón" y "un poco bala"". Mediaset. 26 November 2015.

- Cruz, Luis de la (6 December 2020). "Los chavales de AZCA: cómo el distrito financiero de Madrid fue colonizado por la cultura urbana". Somos Tetuán – via eldiario.es.

- "Pedro Sánchez, Secretaría general" [Pedro Sánchez, Secretary-General]. PSOE (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- Fernando Garea (12 July 2014). "Una carrera guiada por el azar". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- "El currículum de Pedro Sánchez: una tesis... ¿y tres másteres?". COPE. 14 September 2018.

- Iglesias, Leyre (28 February 2016). "Cuando Pedro Sánchez 'negoció' con un criminal de guerra". El Mundo.

- "Diez cosas que quizá desconoces de Pedro Sánchez". La Nueva España. 21 June 2015.

- Pérez Colomé, Jordi (11 June 2019). "Los padrinos del presidente". El País.

- "¿Qué carrera tiene Pedro Sánchez?". El País (in Spanish). 19 November 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- Faber, Sebastiaan (14 December 2015). "Pedro Sánchez: la construcción de un candidato a través de su tesis doctoral". La Marea.

- "El ascenso de Pedro Sánchez: de diputado "desconocido" a secretario general del PSOE" [The rise of Pedro Sánchez: from "unknown" deputy to general secretary of the PSOE]. ABC (in Spanish). 13 July 2014. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- Chicote, Javier (24 September 2018). "Sánchez plagió en su libro 161 líneas con 1.651 palabras de seis textos ajenos y sin ningún tipo de cita". ABC (in Spanish). Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- Tamma, Paola (15 September 2018). "Pedro Sánchez publishes PhD thesis to rebut plagiarism claims". Politico. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- Sánchez Pérez-Castejón, Pedro. "INNOVACIONES DE LA DIPLOMACIA ECONÓMICA ESPAÑOLA: ANÁLISIS DEL SECTOR PÚBLICO (2000–2012)" (PDF). Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- "Pedro Sánchez Voted New Secretary General of Spanish Socialist Party (PSOE) with 49% of Vote | the Spain Report". Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- Gotev, Georgi (16 September 2014). "Spanish socialists to vote against Juncker, Cañete". Euractiv. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- "¿De dónde vienen los votos de Podemos?" [Where do the votes of Podemos come from?]. europa press (in Spanish). 5 November 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- Díez, Anabel (6 July 2015). "Pedro Sánchez, en proceso" [Pedro Sánchez, in process]. El Pais (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- Díez, Anabel (9 November 2014). "Ni fractura, ni independencia, una España federal para todos" [No fracture, no independence, a federal Spain for all]. El Pais (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- SANZ, LUIS ÁNGEL (19 October 2015). "El PSOE eliminará la religión en colegios públicos y privados" [The PSOE to eliminate religion in all public and private schools]. El Mundo(ES) (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- "Sánchez dimite tras ser derrotado por sus críticos y perder la votación sobre primarias y el Congreso 'exprés'". RTVE. 1 October 2016.

- Díez, Anabel; Marcos, José (29 October 2016). "Pedro Sánchez deja el escaño y lanza su candidatura a la secretaría general". El País.

- Ventura, Víctor (1 June 2018). "Pedro Sánchez, el madrileño que no conseguía ser diputado y acabó como presidente de España". Economiahoy.mx.

- Díez, Anabel; Marcos, José (30 October 2016). "Los 15 diputados del PSOE que votaron no". El País.

- Stothard, Michael (8 June 2018). "Pedro Sánchez, a dogged politician who grabbed his chance". Financial Times.

- Zancajo, Silvia (3 June 2018). "Pedro Sánchez, el político de las siete vidas" [Pedro Sánchez, the politician of the seven lives]. El Economista (in Spanish).

- Spanish Socialists re-elect Pedro Sánchez to lead party TheGuardian.com

- Stothard, Michael (4 June 2018). "Spain's Pedro Sánchez forced to confront Catalonia crisis". Financial Times. Nikkei Company. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- Aguado, Jesús; Melander, Ingrid (2 June 2018). "Catalan nationalists back in power, target secession in challenge to Sanchez". Reuters. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- Garcia, Elsa (25 April 2018). "Socialist party chief calls for transitional government". El País. Madrid. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- "Who is Spain's new President of the Government, Pedro Sanchez?". Reuters, AFP. DW. 1 June 2018. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- Ruiz de Almirón, Victor (1 June 2018). "Sánchez llega al poder sin concretar cuándo convocará las elecciones". ABC (in Spanish). Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- Zancajo, Silvia (1 June 2018). "Sánchez prioriza la agenda social y renuncia a realizar reformas en profundidad". El Economista (in Spanish). Editorial Ecoprensa, S.A. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- Merino, Juan Carlos (31 May 2018). "Sánchez ofrece diálogo a Catalunya y mantener los presupuestos al PNV". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- Aduriz, Íñigo (2 June 2018). "Pedro Sánchez promete su cargo de presidente ante el rey y Rajoy, sin crucifijo ni Biblia". El Diario (in Spanish). Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- Jones, Sam (6 June 2018). "Spanish PM appoints 11 women and six men to new cabinet". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- "Pedro Sánchez sets sights on Brussels". POLITICO. 21 November 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- Rios, Beatriz (17 January 2019). "Spanish PM: If Europe protects us, we need to protect Europe". euractiv.com. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- Castro, Irene (19 March 2019). "Sánchez advierte de que los "enemigos" de Europa están "dentro" y llama a votar contra las fuerzas "unidas por sus odios"". eldiario.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "EU nominations 2019: Who is Spain's Josep Borrell? | DW | 03.07.2019". DW.COM. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- "José Luis Escrivá, new Minister of Social Security, Inclusion and Migration". Spain's News. 10 January 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- "Spain to propose Economy Minister Calvino as Eurogroup chief". Reuters. 25 June 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- "Spain not stopping arms sales to Saudi Arabia over Khashoggi killing". El Pais. 22 October 2018.

- Sanz, Luis Ángel; Cruz, Marisa; Villaverde, Susana (24 October 2018). "Pedro Sánchez evita una crisis con Arabia Saudí por el coste electoral en Andalucía". El Mundo.

- "El Gobierno garantiza el contrato de Arabia Saudí con Navantia, cuyos trabajadores han cortado la A-4". RTVE. 7 September 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "How Saudis are getting away with Khashoggi murder". News.com.au. 28 October 2018.

- "Need to keep jobs grounds for continuation of arms sales to Saudi Arabia, argues Spanish president". Catalan News. 24 October 2018.

- "Spain offers itself as hub for Afghans who collaborated with EU". the Guardian. 20 August 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- Rodríguez-Pina, Gloria (21 August 2021). "Von der Leyen considera la acogida de afganos en España "un ejemplo del alma europea"". EL PAÍS (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- "Readout of President Joe Biden's Call with President Pedro Sánchez of Spain". The White House. 21 August 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- "Biden habla con Sánchez tras la afrenta de los agradecimientos por Afganistán". abc (in Spanish). 21 August 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- Rakic, Snezana (2 August 2022). "Spanish PM Sanchez: 'Kosovo independence against international law'". Serbian Monitor. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- Junquera, Natalia (18 June 2018). "Removal of Franco's remains from Valley of the Fallen one step closer". El País (in Spanish). Madrid: Prisa. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- Jones, Sam (23 October 2019). "Franco's remains to finally leave Spain's Valley of the Fallen". The Guardian – via www.theguardian.com.

- "Sánchez aleja un indulto y defiende el fallo: "Garantizamos su absoluto cumplimiento"". El Pais. 14 October 2019.

- "Sánchez defiende en el Congreso los indultos a los presos del 'procés'". El Pais. 30 June 2021.

- "Sánchez: "No habrá referéndum de autodeterminación. Nunca, jamás"". El Pais.

- Daniel Dombey (25 November 2021), Spain passes biggest budget in its history Financial Times.

- Blas, Carlos E. Cué, Claudi Pérez, Elsa García de (13 March 2020). "Sánche decreta el estado de alarma durante 15 días". EL PAÍS (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Health, P. M. N. (14 March 2020). "Spain to impose nationwide lockdown – El Mundo | National Post". National Post.

- Cué, Carlos E. (14 March 2020). "El Gobierno prohíbe todos los viajes que no sean de fuerza mayor". EL PAÍS (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- "Un Constitucional dividido anula el confinamiento domiciliario impuesto en el primer estado de alarma". El Mundo. 14 July 2021.

- Jones, Sam (29 May 2023). "Spain's PM calls snap election after conservative and far-right wins in local polls". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- "Spain's king asks Socialist leader Pedro Sánchez to try to form a government". AP News. 3 October 2023. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

- "Pedro Sánchez: De victoria en victoria hasta la derrota". Letras Libres (in Spanish). 12 November 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- "Pedro Sánchez, el fénix camaleónico". Diario Sur (in Spanish). 22 May 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- "Pedro Sánchez gira a la izquierda y elige al neoliberalismo como gran enemigo del PSOE". Eldiario.es (in Spanish). 20 February 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- "El PSOE y la fatiga democrática". Letras Libres (in Spanish). 28 September 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- Estefanía, Joaquín (21 February 2019). "La ideología de Pedro Sánchez". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- Encarnación, Omar G. "Why Does Spain's Progressive Prime Minister Want to Ban Prostitution?". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- "El misterioso currículum de Begoña Gómez: ni rastro de sus publicitadas titulaciones académicas". El Español (in European Spanish). 14 August 2018. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- "A Conversation with Pedro Sánchez". YouTube. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- Congress of Deputies (Spain). "X Legislatura (2011-Actualidad)Sánchez Pérez-Castejón, Pedro".

- "The teaching of English language in the Spanish education system" (PDF) (in Spanish). Javier Barbero Andrés, University of Cantabria. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- 20 Minutos (25 June 2018). "Así hablaban inglés los presidentes del Gobierno: de los intentos de Aznar al "no, hombre, no" de Rajoy".

- "Pedro Sánchez, primer aspirante a La Moncloa que se declara abiertamente "ateo"" (in Spanish). El Plural. 24 September 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- "Presidente español recibió "emocionado" la medalla de Salvador Allende". Cooperativa (in Spanish). 28 August 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- Torres, Carmen (29 August 2018). "El "hermano presidente Pedro Sánchez" recupera la alianza con Bolivia de Zapatero". El Independiente (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- "Los Reyes ofrecen una cena de gala al presidente de Perú y su esposa en el Palacio Real". HOLA USA. 27 February 2019.

- https://www.quirinale.it/onorificenze/insigniti/370382

- "LA NUEVA DIPLOMACIA ECONÓMICA ESPAÑOLA | PEDRO SANCHEZ PEREZ-CASTEJON | Comprar libro 9788415581512". casadellibro. 26 November 2013.

- Manual de resistencia – Pedro Sánchez | Planeta de Libros – via www.planetadelibros.com.

- Domínguez, Íñigo; Pérez, Fernando J. (14 September 2018). "Un trabajo intrigante". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- Sánchez Pérez-Castejón, Pedro (2019). Manual de resistencia. Madrid: Península. p. 13. ISBN 9788499427959.

- "Irene Lozano sobre el libro de Sánchez: "Yo hice el libro, pero el autor es el presidente"". El Español (in Spanish). 19 February 2019.