American white pelican

The American white pelican (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos) is a large aquatic soaring bird from the order Pelecaniformes. It breeds in interior North America, moving south and to the coasts, as far as Costa Rica, in winter.[2]

| American white pelican | |

|---|---|

| |

| Flying in Dallas, USA | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Pelecaniformes |

| Family: | Pelecanidae |

| Genus: | Pelecanus |

| Species: | P. erythrorhynchos |

| Binomial name | |

| Pelecanus erythrorhynchos Gmelin, 1789 | |

| |

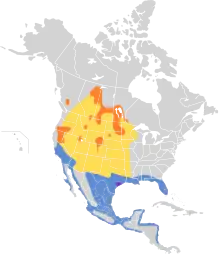

Breeding Migration Year-round Nonbreeding | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Pelecanus erythrorhynchus (lapsus) | |

Taxonomy

The American white pelican was formally described in 1789 by the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin in his revised and expanded edition of Carl Linnaeus's Systema Naturae. He placed it with the other pelicans in the genus Pelecanus and coined the binomial name Pelecanus erythrorhynchos.[3] Gmelin based his description on the "rough-billed pelican" that had been described in 1785 by the English ornithologist John Latham. Latham had access to three specimens that had been brought to London from New York and the Hudson Bay area of North America.[4][5] The scientific name means "red-billed pelican", from the Latin term for a pelican, Pelecanus, and erythrorhynchos, derived from the Ancient Greek words erythros (ἐρυθρός, "red") + rhynchos (ῥύγχος, "bill").[6] The species is monotypic: no subspecies are recognised.[7]

Description

The American white pelican rivals the trumpeter swan, with a similar overall length, as one of the longest birds native to North America. Both very large and plump, it has an overall length of about 50–70 in (130–180 cm), courtesy of the huge beak which measures 11.3–15.2 in (290–390 mm) in males and 10.3–14.2 in (260–360 mm) in females. It has a wingspan of about 95–120 in (240–300 cm).[8] The species also has the second-largest average wingspan of any North American bird, after the California condor. This large wingspan allows the bird to easily use soaring flight for migration. Body weight can range between 7.7 and 30 lb (3.5 and 13.6 kg), although typically these birds average between 11 and 20 lb (5.0 and 9.1 kg).[9] One mean body mass of 15.4 lb (7.0 kg) was reported.[9] Another study found mean weights to be somewhat lower than expected, with eleven males averaging 13.97 lb (6.34 kg) and six females averaging 10.95 lb (4.97 kg).[10] Among standard measurements, the wing chord measures 20–26.7 in (51–68 cm) and the tarsus measures 3.9–5.4 in (9.9–13.7 cm) long.[11] The plumage is almost entirely bright white, except for the black primary and secondary remiges, which are hardly visible except in flight. From early spring until after breeding has finished in mid-late summer, the breast feathers have a yellowish hue. After moulting into the eclipse plumage, the upper head often has a grey hue, as blackish feathers grow between the small wispy white crest.[2]

The bill is huge and flat on the top, with a large throat sac below, and, in the breeding season, is vivid orange in color as is the iris, the bare skin around the eye, and the feet. In the breeding season, there is a laterally flattened "horn" on the upper bill, located about one-third the bill's length behind the tip. This is the only one of the eight species of pelican to have a bill "horn". The horn is shed after the birds have mated and laid their eggs. Outside the breeding season, the bare parts become duller in color, with the naked facial skin yellow and the bill, pouch, and feet an orangy-flesh color.[2]

Apart from the difference in size, males and females look exactly alike. Immature birds have light grey plumage with darker brownish nape and remiges. Their bare parts are dull grey. Chicks are naked at first, then grow white down feathers all over, before moulting to the immature plumage.[2]

Distribution and ecology

.jpg.webp)

American white pelicans nest in colonies of several hundred pairs on islands in remote brackish and freshwater lakes of inland North America. The most northerly nesting colony can be found on islands in the rapids of the Slave River between Fort Fitzgerald, Alberta, and Fort Smith, Northwest Territories. Several groups have been visiting the bird sanctuary at Useless Bay in the state of Washington since 2015. About 10–20% of the population uses Gunnison Island in the Great Basin's Great Salt Lake as a nesting ground. The southernmost colonies are in southwestern Ontario and northeastern California.[2] Nesting colonies exist as far south as Albany County in southern Wyoming.

They winter on the Pacific and Gulf of Mexico coasts from central California and Florida south to Costa Rica, and along the Mississippi River at least as far north as St. Paul, Minnesota. In winter quarters, they are rarely found on the open seashore, preferring estuaries, bays, and lakes. They cross deserts and mountains but avoid the open ocean on migration.[2] But stray birds, often blown off course by hurricanes, have been seen in the Caribbean. In Colombian territory, it was recorded first on February 22, 1997, on the San Andrés Island, where they might have been swept by Hurricane Marco which passed nearby in November 1996. Since then, there have also been a few observations likely to pertain to this species on the Colombian mainland, e.g. at Calamar.[12]

Wild American white pelicans may live for more than 16 years. In captivity, the record lifespan stands at over 34 years.[2]

Food and feeding

Unlike the brown pelican (P. occidentalis), the American white pelican does not dive for its food. Instead, it catches its prey while swimming. Each bird eats more than 4 pounds of food a day.[13] The fish taken by pelicans can range from the size of minnows to 3.5-pound pickerels.[14] Typical fish prey include Cypriniformes like common carp (Cyprinus carpio), Lahontan tui chub (Gila bicolor obesa),[15] minnows,[16] and shiners.[17] Perciformes like Sacramento perch (Archoplites interruptus) or yellow perch (Perca flavescens),[17] Salmoniformes like rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and salmon,[16] Siluriformes (catfish),[18] and jackfish.[19] Other animals eaten by these birds are crayfish, amphibians, and sometimes larval salamanders.[20] Birds nesting on saline lakes, where food is scarce, will travel great distances to better feeding grounds.[2]

American white pelicans like to come together in groups of a dozen or more birds to feed, as they can thus cooperate and corral fish to one another. When this is not easily possible – for example in deep water, where fish can escape by diving out of reach – they prefer to forage alone. But the birds also steal food on occasion from other birds, a practice known as kleptoparasitism. White pelicans are known to steal fish from other pelicans, gulls, and cormorants from the surface of the water and, in one case, from a great blue heron while both large birds were in flight.[2][21]

Reproduction

_in_Green_Bay%252C_WI%252C_2013.JPG.webp)

As noted above, they are colonial breeders, with up to 5,000 pairs per site. The birds arrive on the breeding grounds in March or April; nesting starts between early April and early June. During the breeding season, both males and females develop a pronounced bump on the top of their large beaks. This conspicuous growth is shed by the end of the breeding season.

The nest is a shallow depression scraped in the ground, into which some twigs, sticks, reeds, or similar debris have been gathered. After about one week of courtship and nest-building, the female lays a clutch of usually two or three eggs, sometimes just one, sometimes up to six.

Both parents incubate for about one month. The young leave the nest 3–4 weeks after hatching; at this point, usually only one young per nest has survived. They spend the following month in a creche or "pod", moulting into immature plumage and eventually learning to fly. After fledging, the parents care for their offspring some three more weeks, until the close family bond separates in late summer or early fall, and the birds gather in larger groups on rich feeding grounds in preparation for the migration to the winter quarters. They migrate south by September or October.[2]

Predation

Occasionally, these pelicans may nest in colonies on isolated islands, which is believed to significantly reduce the likelihood of mammalian predation. Red foxes and coyotes prey upon colonies that they can access, and several gulls have been known to prey on pelican eggs and nestlings (including herring, ring-billed, and California gull), as well as common ravens. Young pelicans may be hunted by great horned owls, red-tailed hawks, bald eagles, and golden eagles. The pelicans react to mammalian threats differently from avian threats. Though fairly approachable while feeding, the pelicans may temporarily abandon their nests if a human closely approaches the colony. If the threat is another bird, however, the pelicans do not abandon the nest and may fight off the interloper by jabbing at them with their considerable bills.[22] Full-grown pelicans have few predators. Only Red foxes and coyotes are known to prey on nesting adults on rare occasions.[23]

Status and conservation

This species is protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. It has the California Department of Fish and Game protective status California species of special concern (CSC). On a global scale, however, the species is common enough to qualify as a Species of Least Concern according to the IUCN.[1]

Habitat loss is the largest known cause of nesting failure, with flooding and drought being recurrent problems. Human-related losses include entanglement in fishing gear, boating disturbance, and poaching as well as additional habitat degradation.[24]

There was a pronounced decline in American white pelican numbers in the mid-20th century, attributable to the excessive spraying of DDT, endrin, and other organochlorides in agriculture as well as widespread draining and pollution of wetlands. But populations have recovered well after stricter environmental protection laws came into effect, and are stable or slightly increasing today. By the 1980s, more than 100,000 adult American white pelicans were estimated to exist in the wild, with 33,000 nests altogether in the 50 colonies in Canada, and 18,500 nests in the 14–17 United States colonies. Shoreline erosion at breeding colonies remains a problem in some cases, as are the occasional mass poisonings when pesticides are used near breeding or wintering sites.[2]

References

- BirdLife International (2016). "Pelecanus erythrorhynchos". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22697611A93624242. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22697611A93624242.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- Elliott, Andrew (1992): 6. American White Pelican. In: del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew & Sargatal, Jordi (eds.): Handbook of the Birds of the World (Vol. 1: Ostrich to Ducks): 310, plate 20. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. ISBN 84-87334-10-5

- Gmelin, Johann Friedrich (1789). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae : secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1, Part 2 (13th ed.). Lipsiae [Leipzig]: Georg. Emanuel. Beer. p. 571.

- Latham, John (1785). A General Synopsis of Birds. Vol. 3, Part 2. London: Printed for Leigh and Sotheby. p. 586.

- Mayr, Ernst; Cottrell, G. William, eds. (1979). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 191.

- Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 295, 150. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (August 2022). "Ibis, spoonbills, herons, Hamerkop, Shoebill, pelicans". IOC World Bird List Version 12.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- del Hoyo, J; Elliot, A; Sargatal, J (1996). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 3. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. ISBN 84-87334-20-2.

- CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses by John B. Dunning Jr. (Editor). CRC Press (1992), ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses, 2nd Edition by John B. Dunning Jr. (Editor). CRC Press (2008), ISBN 978-1-4200-6444-5.

- Dorr, Brian S.; King, D. Tommy; Gerard, Patrick; and Spalding, Marilyn G. (2005) "The Use of Culmen Length to Determine Sex of the American White Pelican". USDA National Wildlife Research Center – Staff Publications. Paper 9.

- Estela, Felipe A.; Silva, John Douglas & Castillo, Luis Fernando (2005): El pelícano blanco americano (Pelecanus erythrorhynchus) en Colombia, con comentarios sobre los effectos de los huracanes en el Caribe [The American White Pelican (Pelecanus erythrorhynchus) in Colombia, with comments on the effects of Caribbean hurricanes]. Caldasia 27(2): 271- 275 [Spanish with English abstract]. PDF fulltext

- Knopf, Fritz L. and Roger M. Evans (2004). "American white pelican - Pelecanus erythrorhynchos". U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

- Bent, Arthur Cleveland. Life histories of North American petrels and pelicans and their allies. Vol. 121. US Government Printing Office, 1922.

- "American White Pelican". Truckee River Guide.

- "Pelecanus erythrorhynchos (American white pelican)". Animal Diversity Web.

- BLAIR F. MCMAHON AND ROGER M. EVANS (1992). "NOCTURNAL FORAGING IN THE AMERICAN WHITE PELICAN'" (PDF). Searchable Ornithological Research Archive.

- Montana Natural Heritage Program and Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks. (2018). "American White Pelican - Pelecanus erythrorhynchos". Montana Field Guide.

- Dronen, Norman O.; Blend, Charles K. & Anderson, Christy K. (2003). "Endohelminths from the Brown Pelican, Pelecanus occidentalis, and the American White Pelican, Pelecanus erythrorhynchus, from Galveston Bay, Texas, U.S.A., and Checklist of Pelican Parasites". Comparative Parasitology. 70 (2): 140–154. doi:10.1654/1525-2647(2003)070[0140:EFTBPP]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 85757144.

- Dan A. Tallman; David L. Swanson; Jeffrey S. Palmer (2002). Birds of South Dakota. Aberdeen, South Dakota: Midstates/Quality Quick Print. p. 10. ISBN 0-929918-06-1.

- Nesbitt, S.A.; Folk, M.J. (2003). "Kleptoparasitism of great blue herons by American white pelicans". Florida Field Naturalist. 31 (2): 19–45. Archived from the original on 2014-05-03.

- Dewey, Tanya. Pelecanus erythrorhynchos. Animal Diversity Web

- Knopf, F. L. and R. M. Evans (2020). American White Pelican (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.amwpel.01

- Blood, Donald A.; Hames, Michael; Graham, Arifin; Pawlas, Richard & Friis, Laura (1993) "American White Pelican" Archived February 27, 2009, at the Wayback Machine in Wildlife in British Columbia at Risk. Province of British Columbia Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks. ISBN 0-7726-7466-3

External links

- "American white pelican media". Internet Bird Collection.

- American white pelican profile Archived 2014-09-20 at the Wayback Machine at The Nature Conservancy

- American white pelican pictures from 'Field Guide' page on Flickr

- Stamps (for British Virgin Islands, Canada, Cuba, Turks and Caicos) – with Range Map at bird-stamps.org

- American white pelican photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Photos of the American White Pelican by Klaus Nigge

- Interactive range map of Pelecanus erythrorhynchos at IUCN Red List maps