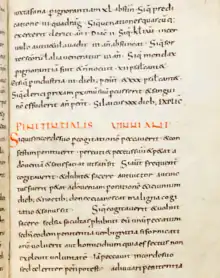

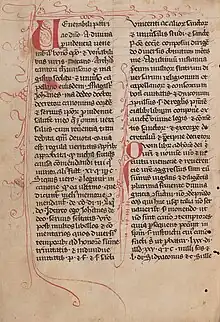

Penitential

A penitential is a book or set of church rules concerning the Christian sacrament of penance, a "new manner of reconciliation with God"[1] that was first developed by Celtic monks in Ireland in the sixth century AD. It consisted of a list of sins and the appropriate penances prescribed for them, and served as a type of manual for confessors.

Origin

Before the church was formalized, there was nothing to correspond with the modern conception of absolution – the pardon or remission of sin by one human being to another.[2] Capitular confession was the ancient public confession. In the primitive Church, confession to God was the only form enjoined. According to St. Clement of Rome the Lord requires nothing of any man save confession to Him. The Didache shows us that this confession was public, in church, and that each believer was expected to confess his transgressions on Sunday, before breaking bread in the Eucharistic feast, for no one was to come to prayer with an evil conscience.[2] The early church taught that the Eucharist itself secured pardon ("...public confession was voluntary and for secret sins; this he says procures admission to the sacrament which removes the sin, showing further that it was the Eucharist that secured pardon").[2]

Even at the end of the 11th century, so indefinite as yet was the value assigned to sacerdotal ministrations that Urban II, at the 1096 council of Nîmes, promulgated a canon asserting that the prayers of monks had more power to wash away sins than those of secular priests.[2]

Confession was not generally recognized by the bishops as a sacrament in the first 1000 years of the church.[2]

Proof texting of various "church fathers" and non-canonical books provides the following: public penance did not necessarily include a public avowal of sin, but was decided by the confessor, and was to some extent determined by whether or not the offence was sufficiently open or notorious to cause scandal to others.[3] Oakley points out that recourse to public penance varied both in time and place, and was affected by the weaknesses of the secular law.[4] The ancient praxis of penance relied on papal decrees and synods, which were translated and collected in early medieval collection. Little of those written rules, however, was retained in the later penitentials.[5]

The earliest important penitentials were those by the Irish abbots Cummean (who based his work on a sixth-century Celtic monastic text known as the Paenitentiale Ambrosianum)[6] and Columbanus, and the Archbishop of Canterbury, Theodore of Tarsus. Most later penitentials are based on theirs, rather than on earlier Roman texts.[5] The number of Irish penitentials and their importance is cited as evidence of the particular strictness of the Irish spirituality of the seventh century.[7] Walter J. Woods holds that "over time the penitential books helped suppress homicide, personal violence, theft, and other offences that damaged the community and made the offender a target for revenge."[8]

According to Thomas Pollock Oakley, the penitential guides first developed in Wales, probably at St. David's, and spread by missions to Ireland.[9] They were brought to Britain with the Hiberno-Scottish mission and were introduced to the Continent by Irish and Anglo-Saxon missionaries.[10]

Praxis

As priests heard confessions, they began to compile unofficial handbooks that dealt with the most confessed sins and wrote down set penances for those sins. Penances would vary given both the severity of the offence and the status of the sinner; such that the penance imposed on a bishop would generally be more severe than that imposed on a deacon for the same offence.[11] For stealing, Cummean prescribed that a layman shall do one year of penance; a cleric, two; a subdeacon three; a deacon, four; a priest, five; a bishop, six.[3]

The list of various penitential acts imposed on the sinner to ensure reparation included more or less rigorous fasts, prostrations, deprivation of things otherwise allowable; also alms, prayers, and pilgrimages. The duration was specified in days, quarantines, or years.[10] Gildas lists the penance for an inebriated monk, "If any one because of drunkenness is unable to sing the Psalms, being stupefied and without speech, he is deprived of dinner."[12]

The penitentials advised the confessor to inquire into the sinner's state of mind and social condition. The priest was told to ask if the sinner before him was rich or poor; educated; ill; young or old; to ask if he or she had sinned voluntarily or involuntarily, and so forth. The spiritual and mental state of the sinner—as well as his or her social status was fundamental to the process. Moreover, some penitentials instructed the priest to ascertain the sinner's sincerity by observing posture and tone of voice.

Penitentials were soon compiled with the authorization of bishops concerned with enforcing uniform disciplinary standards within a given district.

Commutation

The Penitential of Cummean counselled a priest to take into consideration in imposing a penance, the penitent's strengths and weaknesses.[13] Those who could not fast were obliged instead to recite daily a certain number of psalms, to give alms, or perform some other penitential exercise as determined by the confessor.[3]

Some penances could be commuted through payments or substitutions. While the sanctions in early penitentials, such as that of Gildas, were primarily acts of mortification or in some cases excommunication, the inclusion of fines in later compilations derive from secular law, and indicate a church becoming assimilated into the larger society.[13] The connection with the principles embodied in law codes, which were largely composed of schedules of wergeld or compensation, are evident. "Recidivism was always possible, and the commutation of sentence by payment of cash perpetuated the notion that salvation could be bought".[14]

Commutations and the intersection of ecclesiastical penance with secular law both differed from locality to locality. Nor were commutations restricted to financial payments: extreme fasts and recitation of large numbers of psalms could also commute penances; the system of commutation did not reinforce commonplace connections between poverty and sinfulness, even though it favoured people of means and education over those without such advantages. But the idea that whole communities, from top to bottom, richest to poorest, submitted to the same form of ecclesiastical discipline is itself misleading. For example, meat was a rarity in the diet of the poor, with or without the imposition of ecclesiastical fasts. In addition, the system of public penance was not replaced by private penance; the penitentials themselves refer to public penitential ceremonies.

Opposition

The Council of Paris of 829 condemned the penitentials and ordered all of them to be burnt. In practice, a penitential remained one of the few books that a country priest might have possessed. Some argue that the last penitential was composed by Alain de Lille, in 1180. The objections of the Council of Paris concerned penitentials of uncertain authorship or origin. Penitentials continued to be written, edited, adapted, and, in England, translated into the vernacular. They served an important role in the education of priests as well as in the disciplinary and devotional practices of the laity. Penitentials did not go out of existence in the late twelfth century. Robert of Flamborough wrote his Liber Poenitentialis in 1208.

List of penitentials

- Paenitentiale Vinniani

- Canones Adomnani

- Paenitentiale Gildae

- Paenitentialia Columbani

- Paenitentiale Cummeani

- Paenitentiale Theodori

- Paenitentiale Ecgberhti

- Paenitentiale Bedae

- Excarpsus Cummeani

- Paenitentiale Halitgari

- Collectio canonum quadripartita

- Handbook for a Confessor

Notes

- Rouche 1987, p. 528.

- Lea, Henry Charles (1896). A history of auricular confession and indulgences in the Latin church. Wellesley College Library. Philadelphia, Lea brothers & co.

-

Hanna, Edward (1913). "The Sacrament of Penance". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Hanna, Edward (1913). "The Sacrament of Penance". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - Oakley, p.45, n.1.

- Körntgen, Ludger (2006). "Kanonisches Recht und Busspraxis: Zu Kontext und Funktion des Paenitentiale Cummeani". In Pennington, Kenneth; Müller, Wolfgang P.; Sommar, Mary E. (eds.). Medieval church law and the origins of the Western legal tradition: a tribute to Kenneth Pennington. Catholic University of America Excarpsus Press. pp. 17–32. ISBN 978-0-8132-1462-7.

- Körntgen, L. (1993). Studien zu den Quellen der frühmittelalterlichen Bussbücher. Quellen und Forschungen zum Recht im Mittelalter. Vol. 7. Sigmaringen. pp. 257–70.

- Dierkens, Alain (1996). "Willibrord und Bonifatius—Die angelsächsischen Missionen und das Fränkischen Königreich in der ersten Hälfte des 8. Jahrhunderts". Die Franken. Wegbereiter Europas. 5. bis 8. Jahrhundert. Mainz: Von Zabert. pp. 459–65.

- Woods, Walter J. (2010). Walking with Faith: New Perspectives on the Sources and Shaping of Catholic Moral Life. Wipf and Stock. ISBN 9781608992850.

- Oakley, Thomas Pollock (2003) [1923]. English Penitential Discipline and Anglo-Saxon Law in Their Joint Influence. The Lawbook Exchange. p. 28. ISBN 9781584773023.

-

Boudinhon, Auguste (1913). "Penitential Canons". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Boudinhon, Auguste (1913). "Penitential Canons". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - Frantzen, Allen J. "Anglo-Saxon Penitentials: A Cultural Database".

- "Gildas on Penance",

- Davies, Oliver; O'Loughlin, Thomas (1999). Celtic Spirituality. Paulist Press. ISBN 9780809138944.

- Rouche 1987, p. 529.

Sources

- Allen J. Frantzen. The Literature of Penance in Anglo-Saxon England. 1983.

- John T. McNeill and Helena M. Gamer, trans. Medieval Handbooks of Penance. 1938, repr. 1965.

- Pierre J. Payer. Sex and the Penitentials. 1984.

- Rouche, Michel (1987). "The Early Middle Ages in the West: Sacred and Secret". In Veyne, Paul (ed.). A History of Private Life 1: From Pagan Rome to Byzantium. Harvard University Press. pp. 528–9.

- Catholic Encyclopedia: "Penitential Canons" "...have now only an historic interest."

External links

- The Anglo-Saxon Penitentials. A Cultural Database, by Allen J. Frantzen.