Pennsylvania Avenue

Pennsylvania Avenue is a primarily diagonal street in Washington, D.C., and Prince George's County, Maryland, that connects the United States Capitol with the White House and then crosses northwest Washington, D.C. to Georgetown. Traveling through southeast Washington from the Capitol, it enters Maryland, and becomes MD Route 4 (MD 4) and then MD Route 717 in Upper Marlboro, and finally Stephanie Roper Highway.

Pennsylvania Avenue with the U.S. Capitol in the background | |

| Length | 35.1 mi (56.5 km) |

|---|---|

| Location | Washington, D.C. and Prince George's County, Maryland, U.S. |

The section between the White House and Congress is the basis for the Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Site and is sometimes referred to as "America's Main Street";[1] it is the location of official parades and processions, and periodic protest marches. Pennsylvania Avenue is an important commuter road and is part of the National Highway System.[2][3]

Route

The avenue runs for 5.8 miles (9.3 km) in Washington, D.C., but the 1.2 miles (1.9 km) of Pennsylvania Avenue from the White House to the United States Capitol building is far and away the most famed section of the avenue. It continues within the city for 3.5 miles (5.6 km), from the southeast corner of the Capitol grounds through the Capitol Hill neighborhood, and over the Anacostia River on the John Philip Sousa Bridge. Crossing most of Prince George's County, Maryland, it ends 9.5 miles (15.3 km) from the Washington, D.C. border in Maryland at the junction with MD 717 in Upper Marlboro, where the name changes to Stephanie Roper Highway, for a total length of 15.3 miles (24.6 km). Stephanie Roper Highway used to be Pennsylvania Avenue, but was renamed in 2012. In addition to its street names, in Maryland it is designated as Maryland Route 4.

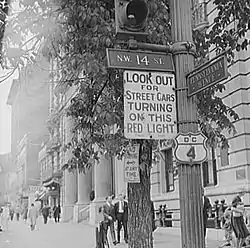

Northwest of the White House, Pennsylvania Avenue runs for 1.4 miles (2.3 km) to its end at M Street N.W. in Georgetown, just beyond the Pennsylvania Avenue Bridge over Rock Creek. From 1862 to 1962, streetcars ran the length of the avenue from Georgetown to the Anacostia River.

History

18th century

Although Pennsylvania Avenue extends six miles (10 km) in Washington, D.C., the expanse between the White House and the United States Capitol constitutes the ceremonial heart of the nation. George Washington called this stretch of Pennsylvania Avenue "most magnificent and most convenient".[4]

The first reference to the street as Pennsylvania Avenue was in a 1791 letter from Thomas Jefferson. One theory behind the avenue's name is that it was named for Pennsylvania as consolation for moving the capital from Philadelphia in 1800 and in recognition of Pennsylvania's historical significance in the nation's founding.[5] Both Jefferson and Washington considered Pennsylvania Avenue an important feature of the new capital. After inspecting L'Enfant's plan, President Washington referred to the thoroughfare as a "grand avenue". Jefferson concurred, and while the "grand avenue" was little more than a wide dirt road ridiculed as "The Great Serbonian Bog", he planted it with rows of fast-growing Lombardy poplars.

Pennsylvania Avenue was designed by Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant, and it was one of the earliest streets constructed in the city.

19th century

In 1832, in an effort to tame dust and dirt on Pennsylvania Avenue, it was paved using the macadam method. But over the years, other pavement methods were trialed on the avenue: cobblestones in 1849 followed by Belgian blocks and then, in 1871, wooden blocks.

In 1876, as part of an initiative begun by President Ulysses S. Grant to see Washington City's streets improved, Pennsylvania Avenue was paved with asphalt by Civil War veteran William Averell[6] using Trinidad and Guanoco lakes asphalt.[7]

20th century

In the early 1900s, the French ambassador to the U.S., Jean Jules Jusserand, popularized the use of L'Enfant's birth name, "Pierre Charles L'Enfant".[8]

Pennsylvania Avenue once provided an unobstructed view between the White House and the Capitol. The construction of an expansion to the Treasury Building blocked this view, and supposedly President Andrew Jackson did this on purpose. Relations between the president and Congress were strained, and Jackson did not want to see the Capitol out his window,[9] though in reality the Treasury Building was simply built on what was cheap government land.

In 1959, Pennsylvania Avenue was extended from the Washington, D.C. border with Maryland to Dower House Road in Upper Marlboro, Maryland.[10]

On September 30, 1965, portions of the avenue and surrounding area were designated the Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Site. The National Park Service administers this area which includes the United States Navy Memorial, Old Post Office Tower, and Pershing Park.[5] After the Great Depression in the 1930s and the move of affluent families to suburbs in the 1950s, Pennsylvania Avenue became increasingly blighted. John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson tried to redevelop the street as part of the New Frontier and Great Society reforms, but the avenue further declined after the 1968 Washington, D.C., riots in the aftermath of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.[11]

In 1972, Congress created the Pennsylvania Avenue Development Corporation (PADC) to rehabilitate the street between the Capitol and the White House, an area seen as blighted. The new organization was given the mandate of developing Pennsylvania Avenue "in a manner suitable to its ceremonial, physical, and historic relationship to the legislative and executive branches of the federal government".[5]

In the 1980s, renovations were made to the Willard Hotel, the Old Post Office, and Washington Union Station, each located on or adjacent to Pennsylvania Avenue.[11]

21st century

In 2010, the District of Columbia designated Pennsylvania Avenue from the southwestern terminus of John Philip Sousa Bridge to the Maryland state line to be a "D.C. Great Street". The city spent $430 million to beautify the street and improve the roadway.[12]

Parades and protests

Presidential inaugurations

Ever since an impromptu procession formed around Jefferson's second inauguration, every U.S. president except Ronald Reagan in his second inauguration in January 1985 has paraded down Pennsylvania Avenue after taking the oath of office. Reagan paraded up the avenue for his first inauguration in January 1981 but not following his second inauguration in 1985 because freezing temperatures and high winds made it dangerous.

Presidential funeral processions

From William Henry Harrison to Gerald Ford, the funeral corteges of seven of the eight presidents who died in office and two former presidents followed this route. Franklin Roosevelt was the only president who died in office whose cortege did not follow this route.

Abraham Lincoln's funeral cortege solemnly proceeded along Pennsylvania Avenue in 1865; only weeks later, the end of the American Civil War was celebrated with the Grand Review of the Armies when the Army of the Potomac paraded more joyously along the avenue. The funeral processions of both Lyndon B. Johnson and Ford funeral corteges proceeded down Pennsylvania Avenue. For Lyndon Johnson, the cortege was along Pennsylvania Avenue from U.S. Capitol to National City Christian Church, where he often worshiped and where his funeral was held. Ford's funeral went up Pennsylvania Avenue, pausing at the White House en route to Washington National Cathedral, where his funeral was held.

Protests and celebrations

In addition to serving as a location for official functions, Pennsylvania Avenue is a traditional parade and protest route of ordinary citizens. During the depression of the 1890s, Jacob Coxey marched 500 supporters down Pennsylvania Avenue to the U.S. Capitol to demand federal aid for the unemployed. Similarly, on the eve of Woodrow Wilson's 1913 inauguration, Alice Paul masterminded a parade, the Woman Suffrage Procession, highlighting the women's suffrage movement. In July 1932, a contingent of the Bonus Expeditionary Force carried flags up Pennsylvania Avenue to the White House, where they formed picket lines.

Pennsylvania Avenue also has served as a background for more lighthearted celebrations, including a series of Shriner's parades in the 1920s and 1930s. Thomas and Concepcion Picciotto are the founders of the White House Peace Vigil, the longest-running anti-nuclear peace vigil in the nation at Lafayette Square on the 1600 block of Pennsylvania Avenue.[13][14]

Security measures

After the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995, the Secret Service closed the portion of Pennsylvania Avenue in front of the White House to all vehicular traffic. Pedestrian and bicycle traffic, however, was still permitted on the sidewalk. After the September 11 attacks, all traffic in front of the White House was prohibited, and traffic near the White House is redirected to H Street or Constitution Avenue, both of which eventually link back with Pennsylvania Avenue.

In 2002, the National Capital Planning Commission invited several prominent landscape architects to submit proposals for the redesign of Pennsylvania Avenue at the White House, with the intention that the security measures would be woven into an overall plan for the precinct and a more welcoming public space might be created. The winning entry by a firm run by Michael Van Valkenburgh proposed a very simple approach to planting, paving, and the integration of required security steps. Construction was completed in 2004.[15]

Sites of interest

From east to west:

The National Theatre and Warner Theatre use Pennsylvania Avenue mailing addresses, although the theaters are nearby on E Street and 13th Street respectively.

Transit service

Metrobus

The following Metrobus routes travel along the street (listed from west to east):

- 30N (Branch Ave. SE to Independence Ave. SE, then 7th St. N.W. to 15th St. N.W., then H St. N.W. to M St. N.W.)

- 30S (Minnesota Ave. SE to Independence Ave. SE, then 7th St. N.W. to 15th St. N.W., then H St. N.W. to M St. N.W.)

- 38B (Eye St. N.W. to M St. N.W.)

- 33 (9th St. N.W. to 15th St. N.W., then H St. N.W. to M St. N.W.)

- 31, D5 (Washington Circle to M St. N.W.)

- 36 (Branch Ave. SE to Independence Ave. SE, then 7th St. N.W. to 15th St. N.W., then H St. N.W. to Washington Circle)

- 32 (Minnesota Ave. SE to Independence Ave. SE, then 7th St. N.W. to 15th St. N.W., then H St. N.W. to Washington Circle)

- 39 (Limited stop service from Southern Ave. to Independence Ave., then 7th St. N.W. to 15th St. N.W., then Eye St. N.W. to Washington Circle)

- 37 (Limited stop service from 7th St. N.W. to 15th St. N.W.)

- 16C (6th St. N.W. to 12th St. N.W.)

- P6 (4th St. N.W. to 11th St. N.W.)

- 34 (Minnesota Ave. SE to Independence Ave. SE)

- M6 (Alabama Ave. SE to Potomac Ave. SE)

- B2, V4 (Minnesota Ave. SE to Potomac Ave. SE)

- V12 (Brooks Dr. to Shadyside Ave.)

- K12 (Forestville Rd. to Parkland Dr., then Walters La. to Donnell Dr.)

- J12 (Eastbound only from Forestville Rd. to Old Marlboro Pike)

DC Circulator

The DC Circulator travels along the street:

- Georgetown-Union Station (20th St. N.W. to M St. N.W.)

MTA Commuter Bus

The following MTA Maryland Commuter Bus routes travel along the street:

- 904 (Anacostia Freeway to Independence Ave., then 7th St. NW to 11th St. NW)

- 905 (7th St. N.W. to 11th St. N.W.)

Bus

The following routes of TheBus serve Pennsylvania Ave. in Prince George's County:

- 24 (Old Silver Hill Rd. to Brooks Dr.)

- 20 (Marlboro Pike to Donnell Dr.)

Washington Metro

The following Washington Metro stations have entrances located near Pennsylvania Avenue:

References

- Pennsylvania Avenue, National Historic Site Archived 2010-08-30 at the Wayback Machine. National Park Service.

- United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on Appropriations. Subcommittee on Transportation and Related Agencies (1995). Department of Transportation and Related Agencies Appropriations for Fiscal Year 1995. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-16-046724-0. Archived from the original on March 3, 2023. Retrieved May 9, 2018.

- Scot Schraufnagel (August 11, 2011). Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Congress. Scarecrow Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-8108-7455-8. Archived from the original on March 3, 2023. Retrieved May 9, 2018.

- Busey, Samuel Clagett (1898). Pictures of the City of Washington in the Past. W. Ballantyne & sons. Archived from the original on March 3, 2023. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- "Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Site and Old Post Office Building". Washington, DC: A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary. National Park Service. Archived from the original on January 21, 2009. Retrieved January 21, 2009.

- Lively, Mathew W. (April 8, 2013). "William Averell Paves the Way to the White House, Literally". Civil War Profiles. Archived from the original on December 19, 2013. Retrieved December 19, 2013.

- McNichol, Dan (2005). "Chapter 4: Asphalting the Avenues". Paving the Way: Asphalt in America. Lanham, Maryland: National Asphalt Pavement Association. pp. 38–55. ISBN 0-914313-04-5.

- Reference: Bowling, Kenneth R (2002). Peter Charles L'Enfant: vision, honor, and male friendship in the early American Republic. George Washington University, Washington, D.C. ISBN 978-0-9727611-0-9

- "FAQs: Main Treasury Building". United States Department of the Treasury. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013. Retrieved September 7, 2013.

- Rowland, James B. (December 1, 1959). "6 Miles of New Road to Beaches Opened". The Evening Star.

- Troy, Gil (December 31, 2013), "1981 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue: The Ronald Reagan Show, the New Dynasty, and David Stockman's Reaganomics", Morning in America, Princeton University Press, pp. 58–59, doi:10.1515/9781400849307.50, ISBN 978-1-4008-4930-7, archived from the original on November 23, 2021, retrieved November 26, 2021

- Thomson, Robert (May 30, 2010). "Patience Required for Travelers on Pennsylvania Avenue". The Washington Post.

- The Oracles of Pennsylvania Avenue Archived 2012-07-10 at archive.today

- Colman McCarthy (February 8, 2009). "From Lafayette Square Lookout, He Made His War Protest Permanent". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 17, 2019. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- Fernandez, Manny (November 10, 2004). "America's Main Street Revisited; Pennsylvania Ave. Reopened to Pedestrians". The Washington Post. p. A01. Archived from the original on July 24, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2017.