Penrhyn Castle

Penrhyn Castle (Welsh: Castell Penrhyn) is a country house in Llandygai, Bangor, Gwynedd, North Wales, constructed in the style of a Norman castle. The Penrhyn estate was founded by Ednyfed Fychan. In the 15th century his descendent Gwilym ap Griffith built a fortified manor house on the site. In the 18th century, the Penrhyn estate came into the possession of Richard Pennant, 1st Baron Penrhyn, in part from his father, a Liverpool merchant, and in part from his wife, Ann Susannah Pennant née Warburton, the daughter of an army officer. Pennant derived great wealth from his ownership of slave plantations in the West Indies and was a strong opponent of attempts to abolish the slave trade. His wealth was used in part for the development of the slate mining industry on Pennant's Caernarfonshire estates, and also for development of Penrhyn Castle. In the 1780s Pennant commissioned Samuel Wyatt to undertake a reconstruction of the medieval house.

| Penrhyn Castle | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Penrhyn Castle - the keep to the right, the main block in the centre and the service wing to the left | |

| Type | Country house |

| Location | Llandygai, Bangor, Wales |

| Coordinates | 53.2259°N 4.0946°W |

| Architect | Thomas Hopper |

| Owner | National Trust |

| Website | Official website |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Penrhyn Castle |

| Designated | 3 March 1966 |

| Reference no. | 3659 |

| Official name | Penrhyn Park |

| Designated | 3 March 1966 |

| Reference no. | PGW(Gd)40(GWY) |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Official name | Grand Lodge and forecourt walling |

| Designated | 3 March 1966 |

| Reference no. | 3661 |

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Official name | Walls and attached structures to terraced flower garden |

| Designated | 11 March 1981 |

| Reference no. | 3 March 1966 |

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Official name | Kitchen garden wall and attached outbuildings |

| Designated | 24 May 2000 |

| Reference no. | 23375 |

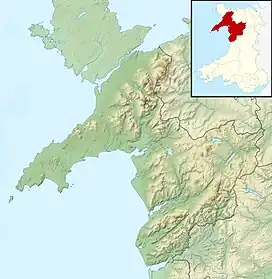

Location of Penrhyn Castle in Gwynedd | |

On Pennant's death in 1808, the Penrhyn estate was inherited by his second cousin, George Hay Dawkins, who adopted the surname Dawkins-Pennant. From 1822 to 1837 Dawkins-Pennant engaged the architect Thomas Hopper who rebuilt the house in the form of a Neo-Norman castle. Dawkins-Pennant, who sat as Member of Parliament for Newark and New Romney, followed his cousin as a long-standing opponent of emancipation, serving on the West India Committee, a group of parliamentarians opposed to the abolition of slavery, on which Richard Pennant had served as chairman. Dawkins-Pennant received significant compensation when, in 1833, emancipation of slaves in the British Empire was eventually achieved, through the passing of the Slavery Abolition Act.

In 1840, the Penrhyn estate passed to Edward Gordon Douglas, through his marriage to Dawkins-Pennant's elder daughter, Juliana. Douglas, who assumed the name Douglas-Pennant, was elevated to the peerage as 1st Baron Penrhyn of the second creation in 1866. He, and his son and heir, George Douglas-Pennant, 2nd Baron Penrhyn, continued the development of their slate interests at Penrhyn Quarry, and of the supporting infrastructure throughout North-West Wales. Firmly opposed to trade unionism at their quarries, their tenure saw bitter strikes over union recognition and workers' rights, culminating in the Great Strike of 1900–1903, the longest dispute in British industrial history. Little development took place at the castle, which was not the family's principal residence and was mainly used as a holiday home in the summer months, but the interior was enhanced by Edward Douglas-Pennant's creation of a major collection of paintings. These provided the setting for entertaining guests, who included Queen Victoria, her son the Prince of Wales and William Gladstone. The castle passed from the family to the National Trust via the National Land Fund in 1951.

Penrhyn Castle is a Grade I listed building, recognised as Thomas Hopper's finest work. Built in the Romanesque Revival style, it is considered one of the most important country houses in Wales and as among the best of the Revivalist castles in Britain. Its art collection, including works by Palma Vecchio and Canaletto is of international importance. In the 21st century, the National Trust's attempts to explore the links between their properties and colonialism and historic slavery have seen the castle feature in the ensuing culture wars.

History

Early owners

In the 15th century, the Penrhyn estate was the centre of a large landholding developed by Gwilym ap Griffith. The land had originally been granted to his ancestor Ednyfed Fychan, Seneschal to Llywelyn the Great.[1] Despite losing his lands temporarily during the Glyndŵr Rising, ap Griffith regained them by 1406 and began the construction of a fortified manor house and adjoining chapel at Penrhyn, which became his family's main home.[1]

17th and 18th centuries

The fortunes of the Pennant family were begun in the late-17th century by a former soldier, Gifford Pennant. Settling in Jamaica, he built up one of the largest estates on the island, eventually comprising four or five slave plantations for the cultivation of sugar cane. His son, Edward, rose to become Chief Justice of Jamaica and by the beginning of the late 18th century the family had accumulated sufficient funds to return to England, invest their profits in the development of their English and Welsh estates, and manage their West Indian properties as absentee landlords.[2]

Edward's grandson, Richard Pennant (1737–1808), acquired the Penrhyn estate in the 18th century, in part from his father, John Pennant, a Liverpool merchant, and in part from his wife, Ann Susannah Pennant, the only child of Hugh Warburton, an army officer.[3] Richard expended his sugar profits on the creation and subsequent development of his North Wales estate, centred on Penrhyn. Recognising the potential for the industrialisation of slate production, he greatly expanded the activities of his main slate mine, Penrhyn Quarry, and invested heavily in the development of the transportation infrastructure necessary for the export of his slate products.[4] A major road-building operation culminated in the creation of Port Penrhyn on the North-Wales coast as the fulcrum of his operations that saw the Bethesda quarries become the world's largest producer of slate by the early 19th century.[5] The profits from sugar and slate enabled Pennant to commission Samuel Wyatt to rebuild the medieval house as a "castellated Gothic" castle.[6]

Richard Pennant was elected Member of Parliament for Liverpool and sat for the city until elevated to the Irish peerage as 1st Baron Penrhyn in 1783. Between 1780 and 1790 he made over thirty speeches defending the slave trade against abolitionist attacks,[7] and became so influential that he was made chairman of the West India Committee, an informal alliance of some 50 MPs dedicated to opposing abolition.[8]

19th and 20th centuries

George Hay Dawkins-Pennant (1764–1840) inherited the Penrhyn Estate on Richard Pennant's death in 1808.[9] He continued the approach adopted by his second cousin: developing the Penrhyn Quarry; opposing the abolition of slavery; serving in Parliament; and building at Penrhyn.[10] Dawkins-Pennant's ambitions for his castle, however, far exceeded those of Richard Pennant for his - the building that Thomas Hopper created for him between 1820 and 1837 is one of the largest castles in Britain.[11] The cost of the construction of this vast house is uncertain, and difficult to quantify as many of the materials came from the family's own forests and quarries and much of the labour from their industrial workforce. Cadw's estimation suggests the castle cost the Pennant family around £150,000, equivalent to some £50m in current values.[12][lower-alpha 1]

The German aristocrat and traveller Hermann, Fürst von Pückler-Muskau recorded his visit to Penrhyn in his memoirs, Tour of a German Prince, published in 1831.[14] He noted the ingenious design of the bell pulls; "a pendulum is attached to each which continues to vibrate for ten minutes after the sound has ceased, to remind the sluggish of their duty."[14] He was even more impressed by the scale of Dawkins-Pennant's ambition; reflecting that castle building, which in the time of William the Conqueror could only be carried out by "mighty" kings, was by the early 19th century, "executed, as a plaything, — only with increased size, magnificence and expense, — by a simple country-gentleman, whose father very likely sold cheeses."[15]

_-_Edward_Gordon_Douglas-Pennant_(1800%E2%80%931886)%252C_1st_Lord_Penrhyn_of_Llandegai_-_1421758_-_National_Trust.jpg.webp)

The eldest of Dawkins-Pennant's two daughters, Juliana, married an aristocratic Grenadier Guardsman, Edward Gordon Douglas (1800–1886), who, on inheriting the estate in 1840, adopted the hyphenated surname of Douglas-Pennant. Edward, the grandson of the 14th Earl of Morton, was created the 1st Baron Penrhyn (second creation) in the Peerage of the United Kingdom in 1866. In accordance with his father-in-law's wishes, he assembled a major collection of pictures for the castle. He was succeeded by his son, George Douglas-Pennant, 2nd Baron Penrhyn, in 1886.[16] He was, in turn, succeeded by his son, Edward Douglas-Pennant, 3rd Baron Penrhyn, who lost his eldest son, and two half-brothers, as casualties in World War I.[17]

Hugh Douglas-Pennant, 4th Baron Penrhyn, who inherited the title and estates in 1927, died in June 1949, when the castle and estate passed to his niece, Lady Janet Pelham, who, following family tradition, adopted the surname of Douglas-Pennant. In 1951, the castle and 40,000 acres (160 km2) of land were accepted by the treasury in lieu of death duties and ownership was transferred to the National Trust.[18]

21st century

The National Trust has held custodianship of Penrhyn Castle since its transfer by the government in 1951. It has worked to conserve the house and its setting, and develop its attraction to visitors. In 2019/2020 Penrhyn received 139,614 such visitors, an increase over the two previous years (118,833 and 109,395).[19][20] In the 21st century, the Trust has sought to develop its understanding and coverage of the links between the house and colonialism and slavery (see below).[21][22][23] The Trust's 2022 Penrhyn Castle website records: "we are accelerating plans to reinterpret the stories of the painful and challenging histories attached to Penrhyn Castle. This will take time as we want to ensure that changes we make are sustained and underpinned by high quality research."[24][lower-alpha 2] A large collection of Douglas-Pennant family papers is held by Bangor University and was catalogued between 2015 and 2017.[26]

Slavery and slate

Slavery

If they passed the vote of abolition they actually struck at seventy millions of property, they ruined the colonies, and by destroying an essential nursery of seamen, gave up the dominion of the sea at a single glance

– Richard Pennant speaking in the House of Commons in 1789[2][lower-alpha 3]

For much of the 20th century, conservation bodies such as the Trust largely ignored the issues of slavery and colonialism in relation to their properties.[28] This position began to change at the very end of the century. In 1995, Alaistair Hennesey published a pioneering article on Penrhyn and slavery in History Today. Of Penrhyn, Hennesey wrote, "there is no building which illustrates so graphically the role which slave plantation profits played in the growth of British economic power."[29] In 2009 the Trust organised a symposium, Slavery and the British Country House, in conjunction with English Heritage and the University of the West of England, which was held at the London School of Economics. At the conference Nicholas Draper (inaugural director of the Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery),[30] discussed the records of the Slave Compensation Commission and their value as a research tool for exploring links between the slave trade and the country house.[31]

.jpg.webp)

In 2020, the Trust published its Interim Report on the Connections between Colonialism and Properties now in the Care of the National Trust, Including Links with Historic Slavery.[32] The appendix to the report recorded that George Hay Dawkins-Pennant was compensated under the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 for being deprived of 764 slaves, being paid £14,683 17s 2d.[33] The report itself provoked a strong reaction. The Common Sense Group of Conservative MPs challenged the Trust's priorities;[34] writing in a joint letter to The Daily Telegraph, "History must neither be sanitised nor rewritten to suit 'snowflake' preoccupations. A clique of powerful, privileged liberals must not be allowed to rewrite our history in their image."[35] The columnist Charles Moore decried the report and stimulated criticism across a range of British media outlets.[36][37][38] A complaint against the Trust's report was lodged with the Charity Commission.[39][lower-alpha 4]

Olivette Otele, Professor of Colonial History and the Memory of Slavery at the University of Bristol, explored the dominant narrative presented at Penrhyn after a visit in 2016. She examined the prevalent history of the Pennants as social, industrial and agrarian improvers and noted the absence of discussion of the slave-owning origins of their wealth.[41] In 2020, the naming of a road in Barry as Ffordd Penrhyn provoked protests over the perceived links with Penrhyn Castle, "the capital of slavery in Wales."[42][43][lower-alpha 5]

Although it had already begun consideration of the links between its properties and the British colonial heritage, the murder of George Floyd and subsequent Black Lives Matter demonstrations, including the toppling of the statue of Edward Colston, led the Trust to acknowledge that these protests had given their efforts a greater impetus. Writing at the time of the interim report's publication, Dr Katie Donnington wrote of the Trust's approach, "Is it scones and tea and a bit of Jane Austen-type fantasy? Does it do critical social history? Or is it a place of escapism where there is a resistance to being confronted with the unsettling realities of empire, race and slavery?"[44]

Slate

I decline altogether to sanction the interference of anybody (corporate or individual) between employer and employed in the working of the quarry

– Lord Penrhyn revoking the recognition agreement with the North Wales Quarrymen's Union that led to the Great Strike of 1900[45]

The Great Strike of 1900–1903 at the Penrhyn Quarry was the longest labour dispute in British history,[46] and left a legacy of lasting bitterness.[47] Its origins lay in earlier instances of industrial unrest relating to the refusal of Lord Penrhyn and his agent to recognise the North Wales Quarrymen's Union.[48] In 2018 local Plaid Cymru councillors accused the Trust of failing to fully recognise the contribution of slate workers to the castle's history.[49]

The 120th anniversary of the strike saw the opening of a commemorative trail, Slate and Strikes in Bethesda. The BBC reported that some inhabitants of the town still declined to visit Penrhyn Castle and resentment against the Douglas-Pennants remained into the 21st-century.[50][51]

Art collection

Penrhyn Castle houses one of the finest art collections in Wales, with works by Canaletto,[52] Richard Wilson,[53] Carl Haag,[54] Perino del Vaga,[55] and Bonifazio Veronese.[56] The collection formerly included a Rembrandt, Catrina Hooghsaet. In 2007 the painting was put up for sale. The Dutch Culture Ministry tried to buy the painting for Amsterdam's Rijksmuseum in 2007, but could not meet the £40m asking price. The painting was subsequently sold to an overseas collector after the lifting of an export ban.[57] In 2016 it was placed on loan to the National Museum Wales for a period of three years.[58]

The collection was almost entirely the work of Edward Douglas-Pennant, who began collecting paintings in the middle of the 19th century; the collection was catalogued by his granddaughter, Alice Douglas-Pennant. His interests were predominantly Dutch landscapes, Spanish pictures and Italian Sacra conversazione.[59] During World War II a large number of pictures from the National Gallery were stored at the castle to avoid the Blitz.[60][lower-alpha 6]

Ownership of the art collection at Penrhyn remained with the Douglas-Pennant family after the castle passed into the ownership of the Trust. Elements have passed directly to the Trust over the following seventy years as the family have ceded ownership in lieu of inheritance tax.[61] Ten paintings were transferred in this way in 2008.[62] In 2016 some forty further works were accepted by the Welsh Government and now form part of the permanent collection.[63]

Architecture and description

Overview and architectural style

.jpg.webp)

Penrhyn is among the most admired of the numerous mock castles built in the United Kingdom in the 19th century;[64] Christopher Hussey called it, "the outstanding instance of Norman revival."[65] The castle is a picturesque composition that stretches over 450 ft (137 m) from a tall donjon, or keep, containing the family rooms, through the main block built around the earlier house, to the service wing and the stables. Simon Jenkins draws comparisons with Windsor, Arundel and Eastnor.[4] Haslam, Orbach and Voelcker, in their 2009 volume Gwynedd in the Pevsner Buildings of Wales series, describe it as "one of the most enormous houses in Britain" and note its "wholeheartedly Romanesque" style.[11] Coflein records that Hopper and Dawkins-Pennant selected the Neo-Norman, or Romanesque Revival style, as opposed to the increasing fashionable Gothic Revival.[66] Pevsner describes the castle as "a serious work of architecture", noting the "dauntingly fine masonry" construction.[11]

Hopper designed all the principal interiors in a rich but restrained Norman style, with much fine plasterwork and wood and stone carving.[67] The castle also has some specially designed Norman-style furniture, including a one-ton slate bed made for Queen Victoria when she visited in 1859.[lower-alpha 7] The diarist Charles Greville recorded his impressions after a visit in 1841: "a vast pile of a building, and certainly very grand, but altogether, though there are some fine things and some good rooms in the house, the most gloomy place I ever saw, and I would not live there if they made me a present of the castle".[69] Some modern critics have been similarly unimpressed; in his study The Architecture of Wales: From the First to the Twenty-First Centuries, John B. Hilling describes the castle as "nightmarishly oppressive, a most uninviting place to live".[70]

Thomas Hopper (1776–1856) made his reputation as architect to the Prince Regent for whom Hopper designed a conservatory in the Gothic style at Carlton House. He was a versatile architect, whose dictum, "it is an architect's business to understand all styles, and to be prejudiced in favour of none", saw him build in the Neo-Norman style, at Penrhyn and at Gosford Castle in Ireland; the cottage orné style at Craven Cottage; Tudor Revival at Margam Castle; Palladianism at Amesbury Abbey; and Jacobethan at Llanover House.[71] Penrhyn Castle is generally considered to be his best work.[12]

Exterior

The castle is arranged in three main parts: the donjon, modelled on Hedingham Castle in Essex, which contained accommodation for the Pennant family;[lower-alpha 8] the central block which contains the state rooms; and the service wing and stables. The castle runs on a north–south axis. The scale is immense, its seventy roofs cover an area of over an acre,[12] and its length, at 440 ft (134 m), which makes it impossible to be viewed in its entirety, disguises variations in the plan caused by the Pennants' desire to incorporate, rather than demolish, elements both of the original medieval house, and Wyatt's earlier castle.[11] The main building material is local rubble, lined internally with brick and externally with limestone ashlar. The masonry is of exceptional quality.[12] The main entrance to the castle is by way of a long drive which transverses the length of the castle before doubling back and passing through a gatehouse into a cour d'honneur in front of the central block.[73]

Grand Hall

The house is entered through a low entrance gallery.[74] This leads into the Grand Hall, which Pevsner considers "a strikingly inventive piece of architecture".[75] Of double height, it resembles the nave or transept of a church.[76] The ceiling forms a triforium supported by compound columns.[12] The hall acts as a junction, to the left entry is to the keep and the family apartments, to the right, the service wing, and ahead stand the state apartments of the main block. A 20th century critic described it as, "about as homely as a railway terminus, admirably suited to house an exhibition of locomotives, or outsize dinosaurs."[76] The stained glass is by Thomas Willement.[12]

Library

Mark Purcell, in his 2019 study, The Country House Library, describes the library at Penrhyn as "not just gargantuan, but exotically and astonishingly opulent."[77] The room is very large and bisected by four, flattened arches. These are plaster, as is the ceiling, but grained and polished to appear as wood.[78] Their decoration, and the design of the arches, draws on that found at the genuinely Norman Church of St Peter at Tickencote in Rutland.[78] The room contains a billiard table constructed entirely of slate and a range of bookcases and furniture designed by Hopper.[78] Haslam, Orbach and Voelcker consider the library the precursor for a long subsequent history of "masculine rooms [for] millionaires".[75] The room still contains the basis of a "good gentleman's library", despite sales of some of the most important and valuable books in the 1950s.[79]

Drawing Room and Ebony Room

The Drawing Room is the reconstructed Great hall of the medieval house, which Samuel Wyatt had previously incorporated into his late 18th-century remodelling.[12] It follows the library in its vaulting and panelling but the decorative style is lighter and more feminine, reflecting its use as a domain for the female members of the Pennant household.[80] Much of the furniture is again by Hopper. The room has large gilt mirrors at either end. The author Catherine Sinclair, who visited in the 1830s, described one as "the largest mirror ever made in this country".[80][lower-alpha 9]

The Ebony Room is named for its ebony panelling and furniture,[81] although much is in fact ebonised rather than real.[82]

.jpeg.webp)

Dining Room and Breakfast Room

These two rooms served a range of purposes. Their primary function as rooms for consumption alternated depending on whether the Pennants were receiving guests; the larger and more formal Dining Room was used when they were, the Breakfast Room when the family was alone at the castle.[83] Their secondary function was to serve as picture galleries for much of the large collection of paintings assembled by Edward Douglas-Pennant; the other main reception rooms offering little space for picture hanging due to their design and decoration.[84]

Grand Staircase

Cadw considers the Grand Staircase, "in many ways the greatest architectural achievement at Penrhyn."[12] It took over ten years to construct,[12] rises the full height of the house culminating in a lantern, its only illumination, and is built of a variety of grey stones decorated with "an orgy of fantastic carving".[85] Haslam, Orbach and Voelcker think it Hopper's tour de force and see parallels with the contemporaneous approach in Gothic Literature, "antiquarian and anarchic, intended to play on the emotions as novels and poems were doing in words."[86]

Bedrooms

.jpeg.webp)

The keep provided accommodation for the family, and important guests, arranged as a series of suites on each of its four main floors. In one of these is the slate bed, intended to accommodate Queen Victoria on her visit in 1859, but within which she refused to sleep.[87] Many of the rooms are carpeted with high-quality Axminster Carpets[88] and with walls papered in handmade Chinese wallpaper.[89]

Service structures

Even by the standards of large, highly variegated, 19th-century country houses, Penrhyn is exceptionally well provided for through its range of service buildings. Rooms within the house include a butler's pantry, a servants' hall, offices for the estate manager and the housekeeper, and the kitchen, with separate still room, pantry and pastry room. Many functions are allocated their own towers, all designed by Hopper to reinforce the impression of a multi-turreted castle. These include the ice tower, the dung tower and the housemaids' tower. The stables are similarly designed to present the appearance of a fortress gatehouse.[12] On the wider estate are located an extensive Home Farm[75] and a range of gate lodges. Not all of these structures have appealed to architectural critics. Mowl and Earnshaw, in their study of lodges and gatehouses Trumpet at a Distant Gate, are particularly dismissive of Hopper's Grand Lodge, and of Hopper more generally. The lodge is condemned as "misapplied historicism"[90] while Hopper himself is censured as a model for the then-coming generation of Victorian architects, his career demonstrating how to "gain a whole world of rich commissions by eclectic dexterity, and still lose his own soul."[91][lower-alpha 10]

Listing designations

The castle is a Grade I listed building. Its Cadw listing designation describes it as "one of the most important country houses in Wales; a superb example of the relatively short-lived Norman Revival of the early 19th century and generally regarded as the masterpiece of its architect, Thomas Hopper."[12] Other listed structures within the estate, all of which are Grade II with the exception of the Grand Lodge which is designated Grade II*, include: the Grand Lodge itself,[92] the Port Lodge and its walls,[93][94] the Tal-y-bont Lodge,[95] the walls to the flower garden,[96] the relocated remnants of the original medieval chapel,[97] a bothy[98] and its walled garden,[99] an estate house,[100] the estate manager's house,[101] the estate kennels,[102] nine buildings at the home farm,[103][104][105][106][107][108][109][110] and the wall surrounding the park.[111]

Gardens and grounds

The castle grounds are an example of the Victorian style of gardening, with specimen trees, rhododenra, and much planting. A conifer was planted by Queen Victoria[112] and another by the Queen of Romania.[113] There is a substantial home farm. The gardens contain a large underground reservoir, constructed in the 1840s and with a capacity of 200,000 gallons. Its purpose is uncertain, it may have been for use by the castle's in-house fire brigade in the event of a fire.[114] The park is listed Grade II* on the Cadw/ICOMOS Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in Wales.[115] The castle and its grounds are part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Slate Landscape of Northwest Wales.[116]

Railway Museum

.jpg.webp)

The Penrhyn Castle Railway Museum is a narrow gauge railway museum. The Pennant's slate quarry at Bethesda was closely associated with the development of industrial narrow-gauge railways, and in particular the Penrhyn Quarry Railway (PQR), one of the earliest industrial railways in the world. In 1951 a museum of railway relics was created in the stable block. The first locomotive donated was Charles, one of the three remaining steam locomotives working on the PQR. A number of other historically significant British narrow-gauge locomotives and other artefacts have since been added to the collection.[81]

Popular culture and events

In 2014, Welsh National Opera used Penrhyn as the location for their filming of Claude Debussy's opera La chute de la maison Usher, based on Edgar Allan Poe's story The Fall of the House of Usher.[117] It has also be used as a television filming location.[118][119] A parkrun takes place in the grounds of the castle each Saturday morning, starting and finishing at the castle gates. The fee to enter the castle grounds is waived for runners.[120]

Gallery

.jpg.webp) Penrhyn Castle - exterior

Penrhyn Castle - exterior.jpg.webp) Penrhyn Castle - exterior

Penrhyn Castle - exterior The Grand Staircase

The Grand Staircase Penrhyn Castle in 2011

Penrhyn Castle in 2011 Carved stonework on the Grand Staircase

Carved stonework on the Grand Staircase.jpg.webp) The Drawing Room

The Drawing Room.jpg.webp) The Library

The Library The Grand Lodge

The Grand Lodge The Victorian Walled Garden

The Victorian Walled Garden

Notes

- By the mid-19th century, the Penrhyn quarries alone were generating around £100,000 income per year, so the build costs were well within the Pennants' means.[13]

- The challenges around coverage of the links between historic buildings, their owners and colonialism and slavery extend to Wikipedia. A 2020 discussion on the Lydney Park Talkpage, on whether to include details of the slave-owning origins of the fortune used to purchase the estate, was referenced in an article, Race, Gender and Wikipedia: How the Global Encyclopaedia Deals with Inequality, published in the Bulletin of the History of Archaeology in May 2021.[25]

- The slave ship Lady Penrhyn was named after Pennant's wife, Anne.[27]

- The Charity Commission concluded that the Trust's Interim Report was carefully researched and in accordance with its charitable objectives.[40]

- Vale of Glamorgan Council denied that the name was chosen to celebrate Penrhyn, saying that it was chosen as being the Welsh language word for peninsula.[43]

- The nocturnal wanderings around the castle of the alcoholic 4th Lord Penrhyn, in the company of his St. Bernard, caused the Gallery staff to fear for the safety of the pictures.[60]

- Victoria and Prince Albert stayed at the castle during a rare visit to Wales in 1859. The Queen reportedly declined to sleep in the specially-commissioned slate bed, as it reminded her of a tomb.[68]

- Hopper served as the county surveyor of Essex for over 40 years.[72]

- At the time of Catherine Sinclair's visit, only one mirror was installed, an organ being placed at the other end. The second mirror is a later replacement, installed when the organ was dismantled.[80]

- Mowl and Earnshaw term the Grand Lodge, Llandegai Lodge.[90]

References

- National Trust 1991, p. 5.

- "Penrhyn Castle and the transatlantic slave trade". National Trust. Archived from the original on 13 September 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- Lloyd, John Edward (1895). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 44. p. 320.

- Jenkins 2008, p. 213.

- National Trust 1991, p. 14.

- National Trust 1991, p. 11.

- Huxtable 2020, p. 14.

- "Richard Pennant (1736-1808)". History of Parliament Online. Archived from the original on 29 August 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- "George Hay Dawkins Pennant Profile & Legacies Summary". Legacies of British Slave-ownership UCL. UCL. Archived from the original on 18 February 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- National Trust 1991, p. 19.

- Haslam, Orbach & Voelcker 2009, p. 399.

- Cadw. "Penrhyn Castle (Grade I) (3659)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- "Penrhyn Castle". DiCamillo. Archived from the original on 3 September 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Girouard 1980, p. 264.

- National Trust 1991, p. 20.

- National Trust 1991, p. 32.

- Cannadine 1992, p. 79.

- National Trust 1991, p. 35.

- "Annual Report 2019/20" (PDF). National Trust. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 January 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- "List of leading visitor attractions". ALVA – Association of Leading Visitor Attractions. p. 423. Archived from the original on 29 July 2015. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- "Penrhyn Castle and the transatlantic slave trade". National Trust. Archived from the original on 13 September 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- "Addressing our histories of colonialism and historic slavery". National Trust. Archived from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Davies, Caroline (22 June 2020). "National Trust hastens projects exposing links of country houses to slavery". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 July 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- "Penrhyn Castle - A brief history". National Trust. Archived from the original on 4 September 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- Moore, Lucy; Nevell, Richard (19 May 2021). "Race, Gender and Wikipedia: How the Global Encyclopaedia Deals with Inequality". Bulletin of the History of Archaeology. 31 (1): 4. doi:10.5334/bha-660.

- "Penrhyn: Sugar & Slate Project-Archives and Special Collections". www.bangor.ac.uk. Bangor University. Archived from the original on 28 August 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Wakelin 2021, p. 41.

- Fowler, Corinne (29 March 2020). "Red walls, green walls: British identity, rural racism and British colonial history". Renewal - Journal of social democracy. Archived from the original on 28 August 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Hennesey 1995, p. 1.

- "Leading Caribbean scholar appointed director of UCL centre examining the impact of British slavery". UCL News. 3 July 2019. Archived from the original on 6 January 2023. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- Draper 2013, p. 18.

- Huxtable 2020, Introduction.

- Bennett, Catherine (27 September 2020). "With its slavery list, the National Trust makes a welcome entry to the 21st century". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- Hinscliff, Gaby (16 October 2021). "Cream teas at dawn: Inside the war for the National Trust". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 August 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- "Letter to the Telegraph". Edward Leigh.org. 11 November 2020. Archived from the original on 3 August 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- Knight, Sam (16 August 2021). "Britain's idyllic country houses reveal a darker history". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 13 September 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- Barker, Alex; Foster, Peter (11 June 2021). "The 'war on woke': who should shape Britain's history?". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- Stubley, Peter (9 November 2020). "National Trust chair denies 'woke takeover' after complaints from members". The Independent. Archived from the original on 4 September 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- "Charity Commission finds that National Trust did not breach charity law". Charity Commission. 11 March 2021. Archived from the original on 29 August 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- Nieri, Richard. "Building the nation's trust - connecting a charity's work to its purpose". Shoosmiths. Archived from the original on 4 September 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- Otele, Gandolfo & Galai 2021, pp. 43–46.

- Wightwick, Abbie (24 July 2020). "Lawyer and black rights activist wants name changed saying it honours a Welsh slave owner". Walesonline. Wales Online. Archived from the original on 3 September 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Harris, Sharon (26 July 2020). "It is the capital of slavery in Wales". Barry & District News. Archived from the original on 3 September 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Davies, Caroline (22 June 2020). "National Trust hastens projects exposing links of country houses to slavery". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 July 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- National Trust 1991, p. 86.

- "Penrhyn Slate Quarry (40564)". Coflein. RCAHMW. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- Gwyn, Marian. "Interpreting the slave trade - The Penrhyn Castle exhibition" (PDF). Brunel University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- "Penrhyn Castle and the Great Penrhyn Quarry Strike 1900-03". National Trust. Archived from the original on 1 August 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- Wyn-Williams, Gareth (20 July 2018). "Row over 'snub' of slate workers whose toil helped build slave-owner's retreat". Daily Post. Archived from the original on 29 August 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- Herd, George (22 November 2022). "Great Strike trail marks 120 years since quarry dispute". BBC News. Archived from the original on 29 August 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- Herd, George (15 April 2017). "Art to help heal Penrhyn Castle's slate strike pain". BBC News. Archived from the original on 29 August 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- "The Thames at Westminster – Item NT1420346". National Trust. Archived from the original on 12 February 2023. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- "Italian Landscape with a House, Gate, Tower and Distant Hills – Item NT1420360". National Trust. Archived from the original on 12 February 2023. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- "The Ruins Of Baalbec – Item NT1420381". National Trust. Archived from the original on 12 February 2023. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- "The Holy Family with Saint John the Baptist – Item NT1420359". National Trust. Archived from the original on 12 February 2023. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- "Sacra Conversazione with Saints Jerome, Justina, Ursula and Bernardino of Siena – Item NT1420347". National Trust. Archived from the original on 12 February 2023. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- Muñoz-Alonso, Lorena (19 October 2015). "UK places export ban on $54 million Rembrandt". Artnet News. Archived from the original on 28 August 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- "£35m Rembrandt painting goes on show in Cardiff". BBC News. 5 April 2016. Archived from the original on 28 August 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- Laing 1995, p. 233.

- Ezard, John (12 December 2002). "How lords wrecked war-time effort to save art". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 August 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- "Cultural Gifts Scheme and Acceptances in Lieu" (PDF). Arts Council. 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 December 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- Clark, Rhodri (23 March 2006). "Penrhyn paintings saved for the nation". WalesOnline. Archived from the original on 28 August 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- "Penrhyn Paintings accepted for the nation". Welsh Government. 13 March 2017. Archived from the original on 28 August 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Davies, Christopher (7 March 2022). "Penrhyn Castle's slavery fortune and how it paid for the North Wales slate industry". North Wales Live. Archived from the original on 23 February 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- Hussey 1988, p. 181.

- "Penrhyn Castle (16687)". Coflein. RCAHMW. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- Port, M. H. (2004). "Hopper, Thomas (1776–1856)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13763. Retrieved 23 January 2013. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Penrhyn Castle". People's Collection Wales. Archived from the original on 29 August 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- "George Hay Dawkins Pennant". History of Parliament Online. Archived from the original on 29 August 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- Hilling 2018, p. 174.

- Colvin 1978, pp. 433–434.

- National Trust 1991, p. 27.

- Haslam, Orbach & Voelcker 2009, p. 400.

- Haslam, Orbach & Voelcker 2009, p. 401.

- Haslam, Orbach & Voelcker 2009, p. 402.

- National Trust 1991, p. 42.

- Purcell 2019, p. 152.

- National Trust 1991, pp. 44–46.

- Purcell 2019, p. 240.

- National Trust 1991, p. 48.

- Greeves 2008, p. 250.

- National Trust 1991, p. 50.

- National Trust 1991, p. 66.

- National Trust 1991, p. 61.

- National Trust 1991, p. 52.

- Haslam, Orbach & Voelcker 2009, p. 403.

- Jenkins 2008, p. 216.

- "Penrhyn Castle". Axminster Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 3 September 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- de Bruijn 2017, p. 166.

- Mowl & Earnshaw 1985, p. 160.

- Mowl & Earnshaw 1985, p. 159.

- Cadw. "Grand Lodge and forecourt walling (Grade II*) (3661)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Cadw. "Port Lodge (Grade II) (3662)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Cadw. "Parapet/Boundary Walls on Port Lodge approach to Penrhyn Castle (Grade II) (23376)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Cadw. "Tal-y-bont Lodge (Grade II) (22925)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Cadw. "Walls and attached structures to terraced flower garden at Penrhyn Castle (Grade II) (3660)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Cadw. "Chapel remains (Grade II) (3658)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Cadw. "Maes-y-Gerddi (Grade II) (23372)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Cadw. "Kitchen garden wall and attached outbuildings at Penrhyn Castle (Grade II) (33375)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Cadw. "Y Berllan (Grade II) (23373)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Cadw. "Plas y Coed (Grade II) (23370)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Cadw. "Estate Kennels (Grade II) (22955)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Cadw. "Northern Cottage at Home Farm (Grade II) (23444)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Cadw. "Southern Cottage at Home Farm (Grade II) (23447)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Cadw. "H-shaped Cowhouse Range to north of main yard at Home Farm (Grade II) (23452)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Cadw. "Cart Shelter Range at Home Farm (Grade II) (23448)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Cadw. "Threshing Barn at Home Farm (Grade II) (23450)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Cadw. "Barn Range between main and outer yards at Home Farm (Grade II) (23454)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Cadw. "Engine House attached to south side of threshing barn at Home Farm (Grade II) (23451)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Cadw. "Cowhouses and Barn in outer yard at Home Farm (Grade II) (33459)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Cadw. "Penrhyn Park boundary wall (partly in Llandygai community) (Grade I) (22957)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- "Penrhyn Castle Gardens (86440)". Coflein. RCAHMW. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- "Queen of Romania's hotel". historypoints.org. Archived from the original on 3 September 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Crump, Eryl (19 March 2016). "Penrhyn Castle's mysterious underground reservoir". North Wales Live. Archived from the original on 4 September 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- Cadw. "Penrhyn Castle (PGW(Gd)40(GWY))". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 6 February 2023.

- "Wales Slate". Gwynedd Council. Archived from the original on 3 September 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Walsh, Stephen (21 June 2014). "The Fall of the House of Usher - Welsh National Opera". The Arts Desk. Archived from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- Leaver, Joel (20 May 2019). "Watchmen trailer provides first glimpse of Penrhyn Castle in new HBO series". North Wales Live.

- "Penrhyn Castle". Flog It!. BBC One. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- "Penrhyn parkrun". Parkrun.org. Archived from the original on 22 September 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

Sources

- de Bruijn, Emile (2017). Chinese Wallpaper in Britain and Ireland. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-781-30054-1.

- Cannadine, David (1992). The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy. London, UK: Pan Books. ISBN 978-0-330-32188-4.

- Colvin, Howard (1978). A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects 1600-1840. London, UK: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-719-53328-0.

- Draper, Nicholas (2013). "Slave ownership and the British country house: the records of the Slave Compensation Commission as evidence". In Madge Dresser; Andrew Hann (eds.). Slavery and the British Country House. Swindon, UK: English Heritage. ISBN 978-1-848-02064-1.

- Girouard, Mark (1980). Life in the English Country House. London, UK: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-140-05406-4.

- Greeves, Lydia (2008). Houses of the National Trust. London, UK: National Trust Books. ISBN 978-1-905-40066-9.

- Haslam, Richard; Orbach, Julian; Voelcker, Adam (2009). Gwynedd. The Buildings of Wales. New Haven, US and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14169-6. OCLC 1023292902.

- Hennesey, Alaistair (1995). "Penrhyn Castle". History Today.

- Hilling, John B. (2018). The Architecture of Wales: From the First to the Twenty-First Centuries. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-1-786-83285-6.

- Hussey, Christopher (1988). English Country Houses: Late Georgian. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors' Club. ISBN 978-1-851-49032-5.

- Huxtable, Sally-Anne (2020). "Wealth, Power and the Global Country House". In Sally-Anne Huxtable; Corrine Fowler; Cristo Kefalas; Emma Slocombe (eds.). Interim Report on the Connections between Colonialism and Properties now in the Care of the National Trust, including links with Historic Slavery (PDF). Swindon, UK: National Trust. OCLC 1266189564.

- Jenkins, Simon (2008). Wales: Churches, Houses, Castles. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-713-99893-1.

- Laing, Alistair (1995). In Trust for the Nation: Paintings from National Trust Houses. London: National Trust. ISBN 978-0-707-80260-2.

- Mowl, Timothy; Earnshaw, Brian (1985). Trumpet At A Distant Gate: The Lodge as Prelude to the Country House. London: Waterstone. ISBN 978-0-947-75205-7.

- National Trust (1991). Penrhyn Castle. Swindon, UK: National Trust. OCLC 66698292.

- Otele, Olivette; Gandolfo, Luisa; Galai, Yoav (2021). Post-Conflict Memorialization: Missing Memorials Absent Bodies. London: Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-030-54887-2.

- Purcell, Mark (2019). The Country House Library. New Haven, US and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-24868-5.

- Wakelin, Peter (2021). The Slave Trade and the British Empire - An Audit of Commemoration in Wales (PDF). Cardiff: Welsh Government. OCLC 8760335359.