Pentropic organisation

The Pentropic organisation was a military organisation used by the Australian Army between 1960 and 1965. It was based on the United States Army's pentomic organisation and involved reorganising most of the Army's combat units into units based on five elements, rather than the previous three or four sub-elements. The organisation proved unsuccessful, and the Army reverted to its previous unit structures in early 1965.

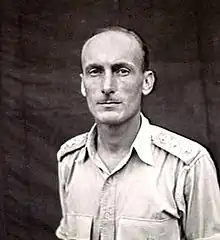

.JPG.webp)

History

The decision to adopt the Pentropic organisation was driven by a desire to modernise the Army and ensure that Australian units were able to integrate with those of the United States Army. While the US Pentomic organisation had been implemented in 1957 to improve the Army's ability to operate during a nuclear war, the Australian organisation was optimised for limited wars in South East Asia in which there was a chance that nuclear weapons might be used. Both structures were designed to facilitate independent operations by the sub-units of divisions. The Australian Pentropic division was intended to be air portable, capable of fighting in a limited war and capable of conducting anti-guerrilla operations.[2]

The key element of the Pentropic organisation was the reorganisation of divisions into five combined arms battle groups. These battle groups consisted of an infantry battalion, field artillery regiment, engineer field squadron and other combat and logistic elements, including armoured, aviation and armoured personnel carrier units as required. These battle groups would be commanded by the commanding officer of their infantry battalion and report directly to the headquarters of the division as brigade headquarters were abolished as part of the reorganisation.[3]

When the Pentropic organisation was implemented in 1960 the Australian Army was reorganised from three divisions organised on what was called the Tropical establishment (the 1st, 2nd and 3rd divisions) into two Pentropic divisions (the 1st and 3rd).[4] While two of the Army's three regular infantry battalions were expanded into the new large Pentropic battalions, the 30 reserve Citizens Military Force (CMF) battalions were merged into just nine battalions.[5] This excluded the University Regiments and the Papua New Guinea Volunteer Rifles which remained unchanged.[6] There was a similar effect on the other CMF units, with most being merged into new, larger units. The other regular infantry battalion remained on the previous tropical establishment as it formed part of the 28th Commonwealth Brigade in Malaysia.[4] As part of this reorganisation the Army replaced its outdated weapons with more modern weapons, most of which were supplied from the United States. It was believed that these new weapons would further improve the Army's combat power and the ability of sub-units to operate independently.[4]

The Pentropic organisation was trialled during exercises in 1962 and 1963. These exercises revealed that the battle groups' command and control arrangements were unsatisfactory, as battalion headquarters were too small to command such large units in combat situations. While the large Pentropic infantry battalions were found to have some operational advantages over the old tropical establishment battalions, the divisions' large number of vehicles resulted in traffic jams when operating in tropical conditions.[3]

The experience gained from exercises and changes in Australia's strategic environment led to the decision to move away from the Pentropic organisation in 1964. During the early 1960s a number of small counter-insurgency wars broke out in South East Asia, and the large Pentropic infantry battalions were ill-suited to these sorts of operations. As the US Army had abandoned its pentomic structure in 1962 and the British Army remained on the tropical establishment, the Australian Army was unable to provide forces which were suited for the forms of warfare it was likely to experience or which were organised along the same lines as units from Australia's main allies. In addition, concentrating the Army's limited manpower into a small number of large battalions was found to be undesirable as it reduced the number of deployable units in the Army. As a result of these factors the Australian Government decided to return the Army to the tropical establishment in November 1964 as part of a wide-ranging package of reforms to the Australian military, which included increasing the size of the Army.[4] The Army returned to the tropical establishment in 1965, and many of the CMF battalions were re-established as independent units.[8]

Structure

The main elements of the Pentropic divisions were:[9]

- Divisional Headquarters

- Reconnaissance Squadron

- Administration Troop

- Survey Troop

- Five reconnaissance troops

- Armoured Regiment

- Three tank squadrons

- Artillery Headquarters

- Five field artillery regiments

- Field engineer regiment

- Five field squadrons

- Five infantry battalions

- Administration Company

- Support Company

- Five rifle companies

- Four rifle platoons

- Weapons platoon

- Reconnaissance Squadron

- Light aviation company

- Signals Regiment

- Supply, transport, ordnance and other services

Notes

- Clark, Chris. Pollard, Sir Reginald George (1903–1978). Retrieved 2 May 2015.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Kuring 2004, pp. 261–262.

- Kuring 2004, pp. 263–264.

- Horner (1997). From Korea to Pentropic: The Army in the 1950s and early 1960s.

- Kuring 2004, p. 265.

- Blaxland 1989, p.83.

- Grey, The Australian Army, p. 209

- Australian Army History Unit (2004). "The Pentropic Organisation 1960–65". Army History Unit website. Australian Department of Defence. Archived from the original on August 30, 2007. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- Blaxland 1989, p. 119.

References

- Australian Army History Unit (2004). "The Pentropic Organisation 1960–65". Army History Unit website. Australian Department of Defence. Archived from the original on August 30, 2007. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- Blaxland, John (1989). Organising an Army: The Australian Experience 1957–1965. Canberra Papers on Strategy and Defence. Vol. No. 50. Canberra: Australian National University. ISBN 0731505301.

- Grey, Jeffrey (2001). Australian Centenary History of Defence: Volume I – The Australian Army. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-554114-6.

- Horner, David (1997). "From Korea to Pentropic: The Army in the 1950s and early 1960s". In Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey (eds.). The Second Fifty Years: The Australian Army 1947–97. Canberra: School of History, University College, UNSW, ADFA.

- Kuring, Ian (2004). Red Coats to Cams. A History of Australian Infantry 1788 to 2001. Sydney: Australian Military History Publications. ISBN 1-876439-99-8.

- Palazzo, Albert (2001). The Australian Army: A History of its Organisation 1901–2001. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-551507-2.

- Ryan, Alan (2003). 'Putting Your Young Men in the Mud'. Change, Continuity and the Australian Infantry Battalion (PDF). Canberra: Land Warfare Studies Centre. ISBN 0-642-29595-6. Retrieved 2008-08-23.

Further reading

- "The Pentropic Division". Australian Army Journal (129). February 1960. – special edition setting out the Pentropic organisation in detail

- "Equipment for the Pentropic Division". Australian Army Journal (134). July 1960. – special edition focused on the equipment issued to Pentropic units

- Chadwick, Justin (2021). "The Atomic Division: The Australian Army Pentropic Experiment, 1959–1965". Australian Army Journal. XVII (1): 45–60.