Aortic valvuloplasty

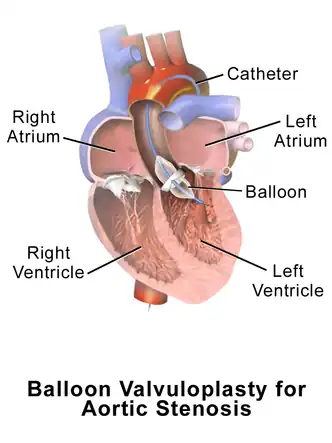

Aortic valvuloplasty, also known as balloon aortic valvuloplasty (BAV), is a procedure used to improve blood flow through the aortic valve in conditions that cause aortic stenosis, or narrowing of the aortic valve. It can be performed in various patient populations including fetuses, newborns, children, adults, and pregnant women.[1][2] The procedure involves using a balloon catheter to dilate the narrowed aortic valve by inflating the balloon.[1]

Medical uses

Guidelines and indications are specific to different patient populations. For adults with aortic stenosis, guidelines suggest that balloon aortic valvuloplasty (BAV) is to be used as a temporary procedure to improve blood flow through the aortic valve to alleviate symptoms and stabilize clinically before having more invasive procedures done, including aortic valve replacement (AVR) or transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI). The most common conditions that deem patients too unstable for AVR or TAVI are pulmonary edema and cardiogenic shock, which BAV attempts to correct to stabilize the patient before definitive surgery.[1][3][4][5] For adult patients with aortic stenosis who need noncardiac related surgeries, BAV can be indicated to decrease the risk of the operation in certain high-risk patients.[1][3] BAV has been used in adult patients who have shortness of breath and the cause is unclear between aortic stenosis or from a primary lung problem. These patients undergo BAV and if their shortness of breath improves, the cause is deemed to be likely from aortic stenosis and they can undergo AVR or TAVI to correct the aortic stenosis definitively.[3][4] BAV can also be used as palliation therapy to improve symptoms in patients who cannot undergo AVR or TAVI due to contraindications.[3][1][5]

BAV has been performed on fetuses with congenital heart defects involving the aortic valve to improve blood flow within the heart. It is not definitive treatment, but is performed in an attempt to prevent a condition called hypoplastic left heart syndrome.[1] For neonates and children with congenital aortic valve stenosis, BAV is commonly the first type of procedure performed to relieve the stenosis, but is not always a definitive treatment option.[6][1][5]

Guidelines suggest performing BAV in pregnant patients with severe aortic stenosis evident by severe symptoms. Changes in blood flow and circulation during pregnancy make it more likely for complications and symptoms to arise in patients with aortic stenosis. When BAV is indicated, it is suggested to attempt to wait until the third trimester to avoid harm to the fetal thyroid from the contrast dye needed during the procedure.[1][2]

Technique

Aortic valvuloplasty relies on placing a catheter with a balloon at the tip in the aortic valve, which is then inflated to widen the narrowed valve.[1] In order to reach the aortic valve, a blood vessel is punctured to introduce the catheter and advance it into the aortic valve. The most common site of entry is the femoral artery in the groin, but the carotid artery in the neck can also be used. The umbilical artery is used when the procedure is performed on a fetus.[1][7] There has also been success using the radial artery in the wrist to gain access.[7] Ultrasound is commonly used to visualize the vessel being accessed to avoid potential complications.[3] A wire is typically used to guide the balloon catheter from the access site to the aortic valve.[1] Different size balloons are used depending on the age of the patient.[1] In order for the balloon to remain in the proper position while it is being inflated in the aortic valve, blood flow through the valve needs to be temporarily reduced. This is typically achieved by increasing the heart rate through electrical stimulation of the heart muscle or through medications that decrease blood pumping from the left ventricle.[1] The blood pressure and flow across the aortic valve is monitored and repeated inflation of the balloon is sometimes needed to successfully dilate the aortic valve.[1]

Outcomes

After BAV in adults, it is common to have both clinical and symptomatic improvement early on. Clinically, the pressure across the aortic valve is reduced, there is increased blood flow, and the area of the aortic valve is increased due to mechanical dilation of the balloon. Many patients have a reduction of the symptoms associated with severe aortic stenosis, commonly reported as an improvement of their NYHA functional class, which is a way to categorize the severity of heart failure based on reported symptoms.[8] The early benefits of BAV in adults typically do not last. The aortic valve becomes narrow again within months.[8][1] These patients may progress to more definitive treatment such as AVR or TAVI if they are eligible and clinically stable.[4][1] BAV in adults has risks and complications associated with it due to the risk of the procedure itself as well as the commonly high-risk patient population that undergoes BAV. Major bleeding, stroke, aortic regurgitation, and death have been reported.[8] Other complications reported include but are not limited to infection, damage to the artery being accessed, heart arrythmias, and decreased kidney function.[3][1][8]

It is typical for children to require reintervention after having BAV, whether it be a repeat BAV or more definitive treatment with surgical aortic valve replacement.[6] Many do not require surgical aortic valve replacement until later on in life, with many patients reaching adulthood before this occurs.[9][1] The outcomes are worse for neonates and infants. This is largely because earlier intervention is required in these patients due to being less clinically stable.[1] A common complication of BAV in children is aortic regurgitation, which decreases in frequency the older the child is when the procedure occurs.[1] Other complications include arrythmias, damage to the artery being accessed, as well as death.[1][9]

For pregnant patients, data is lacking regarding outcomes of BAV. It is recommended that these patients requiring BAV progress to aortic valve replacement when suitable. Specific risks of performing BAV in pregnant patients include potential harm to the fetus from radiation exposure.[2]

References

- Olasińska-Wiśniewska, Anna; Trojnarska, Olga; Grygier, Marek; Lesiak, Maciej; Grajek, Stefan (2013). "Percutaneous balloon aortic valvuloplasty in different age groups". Advances in Interventional Cardiology. 1 (1): 61–74. doi:10.5114/pwki.2013.34029. ISSN 1734-9338. PMC 3915944. PMID 24570692.

- Maskell, Perry; Burgess, Mika; MacCarthy‐Ofosu, Beverly; Harky, Amer (May 2019). "Management of aortic valve disease during pregnancy: A review". Journal of Cardiac Surgery. 34 (5): 239–249. doi:10.1111/jocs.14039. ISSN 0886-0440. PMID 30932245.

- Dall'Ara, Gianni; Tumscitz, Carlo; Grotti, Simone; Santarelli, Andrea; Balducelli, Marco; Tarantino, Fabio; Saia, Francesco (June 2021). "Contemporary balloon aortic valvuloplasty: Changing indications and refined technique". Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 97 (7). doi:10.1002/ccd.28807. ISSN 1522-1946. PMID 32096927. S2CID 211476150.

- Nwaejike, Nnamdi; Mills, Keith; Stables, Rod; Field, Mark (2015-03-01). "Balloon aortic valvuloplasty as a bridge to aortic valve surgery for severe aortic stenosis". Interactive CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery. 20 (3): 429–435. doi:10.1093/icvts/ivu398. ISSN 1569-9285. PMID 25487231.

- Boskovski, Marko T.; Gleason, Thomas G. (2021-04-30). "Current Therapeutic Options in Aortic Stenosis". Circulation Research. 128 (9): 1398–1417. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.318040. ISSN 0009-7330. PMID 33914604.

- Saung, May T; McCracken, Courtney; Sachdeva, Ritu; Petit, Christopher J (2015-11-10). "Abstract 19440: Reintervention Rates Following Balloon Aortic Valvuloplasty versus Surgical Valve Repair in Isolated Congenital Aortic Valve Stenosis - A Meta-analysis". Circulation. 132 (suppl_3). doi:10.1161/circ.132.suppl_3.19440. ISSN 0009-7322.

- Villablanca, Pedro A.; Frisoli, Tiberio; O’Neill, William; Eng, Marvin (January 2020). "Using the Arm for Structural Interventions". Interventional Cardiology Clinics. 9 (1): 63–74. doi:10.1016/j.iccl.2019.08.007. PMID 31733742. S2CID 208144483.

- Baber, Usman; Kini, Annapoorna S.; Moreno, Pedro R.; Sharma, Samin K. (August 2013). "Aortic Stenosis". Cardiology Clinics. 31 (3): 327–336. doi:10.1016/j.ccl.2013.05.005. PMID 23931097.

- Singh, Gautam K. (2019-05-13). "Congenital Aortic Valve Stenosis". Children. 6 (5): 69. doi:10.3390/children6050069. ISSN 2227-9067. PMC 6560383. PMID 31086112.