Substitute good

In microeconomics, two goods are substitutes if the products could be used for the same purpose by the consumers.[1] That is, a consumer perceives both goods as similar or comparable, so that having more of one good causes the consumer to desire less of the other good. Contrary to complementary goods and independent goods, substitute goods may replace each other in use due to changing economic conditions.[2] An example of substitute goods is Coca-Cola and Pepsi; the interchangeable aspect of these goods is due to the similarity of the purpose they serve, i.e fulfilling customers' desire for a soft drink. These types of substitutes can be referred to as close substitutes.[3]

Substitute goods are commodity which the consumer demanded to be used in place of another good.

Economic theory describes two goods as being close substitutes if three conditions hold:[3]

- products have the same or similar performance characteristics

- products have the same or similar occasion for use and

- products are sold in the same geographic area

Performance characteristics describe what the product does for the customer; a solution to customers' needs or wants.[3] For example, a beverage would quench a customer's thirst.

A product's occasion for use describes when, where and how it is used.[3] For example, orange juice and soft drinks are both beverages but are used by consumers in different occasions (i.e. breakfast vs during the day).

Two products are in different geographic market if they are sold in different locations, it is costly to transport the goods or it is costly for consumers to travel to buy the goods.[3]

Only if the two products satisfy the three conditions, will they be classified as close substitutes according to economic theory. The opposite of a substitute good is a complementary good, these are goods that are dependent on another. An example of complementary goods are cereal and milk.

An example of substitute goods are tea and coffee. These two goods satisfy the three conditions: tea and coffee have similar performance characteristics (they quench a thirst), they both have similar occasions for use (in the morning) and both are usually sold in the same geographic area (consumers can buy both at their local supermarket). Some other common examples include margarine and butter, and McDonald's and Burger King.

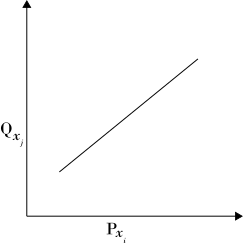

Formally, good is a substitute for good if when the price of rises the demand for rises, see figure 1.

Let be the price of good . Then, is a substitute for if: .

Cross elasticity of demand

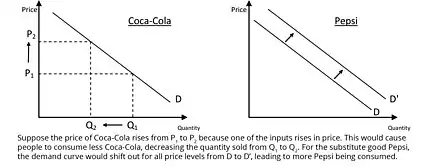

The fact that one good is substitutable for another has immediate economic consequences: insofar as one good can be substituted for another, the demands for the two goods will be interrelated by the fact that customers can trade off one good for the other if it becomes advantageous to do so. Cross-price elasticity helps us understand the degree of substitutability of the two products. An increase in the price of a good will (ceteris paribus) increase demand for its substitutes, while a decrease in the price of a good will decrease demand for its substitutes, see Figure 2.[4]

The relationship between demand schedules determines whether goods are classified as substitutes or complements. The cross-price elasticity of demand shows the relationship between two goods, it captures the responsiveness of the quantity demanded of one good to a change in price of another good.[5]

Cross-Price Elasticity of Demand (Ex,y) is calculated with the following formula:

Ex,y = Percentage Change in Quantity Demanded for Good X / Percentage Change in Price of Good Y

The cross-price elasticity may be positive or negative, depending on whether the goods are complements or substitutes. A substitute good is a good with a positive cross elasticity of demand. This means that, if good is a substitute for good , an increase in the price of will result in a leftward movement along the demand curve of and cause the demand curve for to shift out. A decrease in the price of will result in a rightward movement along the demand curve of and cause the demand curve for to shift in. Furthermore, perfect substitutes have a higher cross elasticity of demand than imperfect substitutes do.

Types

Perfect substitutes

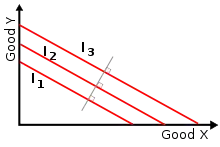

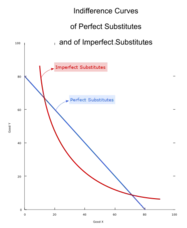

Perfect substitutes refer to a pair of goods with uses identical to one another.[6] In that case, the utility of a combination of the two goods is an increasing function of the sum of the quantity of each good. That is, the more the consumer can consume (in total quantity), the higher level of utility will be achieved, see figure 3.

Perfect substitutes have a linear utility function and a constant marginal rate of substitution, see figure 3.[7] If goods X and Y are perfect substitutes, any different consumption bundle will result in the consumer obtaining the same utility level for all the points on the indifference curve (utility function).[8] Let a consumption bundle be represented by (X,Y), then, a consumer of perfect substitutes would receive the same level of utility from (20,10) or (30,0).

Consumers of perfect substitutes base their rational decision making process on prices only. Evidently, the consumer will choose the cheapest bundle to maximise their profits.[8] If the prices of the goods differed, there would be no demand for the more expensive good. Producers and sellers of perfect substitute goods directly compete with each other, that is, they are known to be in direct price competition.[9]

An example of perfect substitutes is butter from two different producers; the producer may be different but their purpose and usage are the same.

Perfect substitutes have a high cross-elasticity of demand. For example, if Country Crock and Imperial margarine have the same price listed for the same amount of spread, but one brand increases its price, its sales will fall by a certain amount. In response, the other brand's sales will increase by the same amount.

Imperfect substitutes

Imperfect substitutes, also known as close substitutes, have a lesser level of substitutability, and therefore exhibit variable marginal rates of substitution along the consumer indifference curve. The consumption points on the curve offer the same level of utility as before, but compensation depends on the starting point of the substitution. Unlike perfect substitutes (see figure 4), the indifference curves of imperfect substitutes are not linear and the marginal rate of substitution is different for different set of combinations on the curve. Close substitute goods are similar products that target the same customer groups and satisfy the same needs, but have slight differences in characteristics.[9] Sellers of close substitute goods are therefore in indirect competition with each other.

Beverages are a great example of imperfect substitutes. As the price of Coca-Cola rises, consumers could be expected to substitute to Pepsi. However, many consumers prefer one brand over the other. Consumers who prefer one brand over the other will not trade between them one-to-one. Rather, a consumer who prefers Coca-Cola (for example) will be willing to exchange more Pepsi for less Coca-Cola, in other words, consumers who prefer Coca-Cola would be willing to pay more.

The degree to which a good has a perfect substitute depends on how specifically the good is defined. The broader the definition of a good, the easier it is for the good to have a substitute good. On the other hand, a good narrowly defined will be likely to not have a substitute good. For example, different types of cereal generally are substitutes for each other, but Rice Krispies cereal, which is a very narrowly defined good as compared to cereal generally, has few, if any substitutes. To illustrate this further, we can imagine that while both Rice Krispies and Froot Loops are types of cereal, they are imperfect substitutes, as the two are very different types of cereal. However, generic brands of Rice Krispies, such as Malt-o-Meal's Crispy Rice would be a perfect substitute for Kellogg's Rice Krispies.

Imperfect substitutes have a low cross-elasticity of demand. If two brands of cereal have the same prices before one's price is raised, we can expect sales to fall for that brand. However, sales will not raise by the same amount for the other brand, as there are many types of cereal that are equally substitutable for the brand which has raised its price; consumer preferences determine which brands pick up their losses.

Gross and net substitutes

If two goods are imperfect substitutes, economists can distinguish them as gross substitutes or net substitutes. Good is a gross substitute for good if, when the price of good increases, spending on good increases, as described above. Gross substitutability is not a symmetric relationship. Even if is a gross substitute for , it may not be true that is a gross substitute for .

Two goods are net substitutes when the demand for good X increases when the price of good Y increases and the utility derived from the substitute remains constant.[10]

Goods and are said to be net substitutes if

That is, goods are net substitutes if they are substitutes for each other under a constant utility function. Net substitutability has the desirable property that, unlike gross substitutability, it is symmetric:

That is, if good is a net substitute for good , then good is also a net substitute for good . The symmetry of net substitution is both intuitively appealing and theoretically useful.[11]

The common misconception is that competitive equilibrium is non-existent when it comes to products that are net substitutes. Like most times when products are gross substitutes, they will also likely be net substitutes, hence most gross substitute preferences supporting a competitive equilibrium also serve as examples of net substitutes doing the same. This misconception can be further clarified by looking at the nature of net substitutes which exists in a purely hypothetical situation where a fictitious entity interferes to shut down the income effect and maintain a constant utility function. This defeats the point of a competitive equilibrium, where no such intervention takes place. The equilibrium is decentralized and left to the producers and consumers to determine and arrive at an equilibrium price.[12]

Within-category and cross-category substitutes

Within-category substitutes are goods that are members of the same taxonomic category such as goods sharing common attributes (e.g., chocolate, chairs, station wagons).

Cross-category substitutes are goods that are members of different taxonomic categories but can satisfy the same goal. A person who wants chocolate but cannot acquire it, for example, might instead buy ice cream to satisfy the goal of having a dessert.[13]

Whether goods are cross-category or within-category substitutes influences the utility derived by consumers. People exhibit a strong preference for within-category substitutes over cross-category substitutes, despite cross-category substitutes being more effective at satisfying customers' needs.[14] Across ten sets of different foods, 79.7% of research participants believed that a within-category substitute would better satisfy their craving for a food they could not have than a cross-category substitute. Unable to acquire a desired Godiva chocolate, for instance, a majority reported that they would prefer to eat a store-brand chocolate (a within-category substitute) than a chocolate-chip granola bar (a cross-category substitute). This preference for within-category substitutes appears, however, to be misguided. Because within-category substitutes are more similar to the missing good, their inferiority to it is more noticeable. This creates a negative contrast effect, and leads within-category substitutes to be less satisfying substitutes than cross-category substitutes.[13]

Unit-demand goods

Unit-demand goods are categories of goods from which consumer wants only a single item. If the consumer has two unit-demand items, then his utility is the maximum of the utilities he gains from each of these items. For example, consider a consumer that wants a means of transportation, which may be either a car or a bicycle. The consumer prefers a car to a bicycle. If the consumer has both a car and a bicycle, then the consumer uses only the car. The economic theory of unit elastic demand illustrates the inverse relationship between price and quantity.[15] Unit-demand goods are always substitutes.[16]

In perfect and monopolistic market structures

Perfect competition

Perfect competition is solely based on firms having equal conditions and the continuous pursuit of these conditions, regardless of the market size [17] One of the requirements for perfect competition is that the goods of competing firms should be perfect substitutes. Products sold by different firms have minimal differences in capabilities, features, and pricing. Thus, buyers cannot distinguish between products based on physical attributes or intangible value.[18] When this condition is not satisfied, the market is characterized by product differentiation. A perfectly competitive market is a theoretical benchmark and does not exist in reality. However, perfect substitutability is significant in the era of deregulation because there are usually several competing providers (e.g., electricity suppliers) selling the same good which result in aggressive price competition.

Monopolistic competition

Monopolistic competition characterizes an industry in which many firms offer products or services that are close, but not perfect substitutes. Monopolistic firms have little power to set curtail supply or raise prices to increase profits.[19] Thus, the firms will try to differentiate their product through branding and marketing to capture above market returns. Some common examples of monopolistic industries include gasoline, milk, Internet connectivity (ISP services), electricity, telephony, and airline tickets. Since firms offer similar products, demand is highly elastic in monopolistic competition.[20] As a result of demand being very responsive to price changes, consumers will switch to the cheapest alternative as a result of price increases. This is known as switching costs, or essentially what the consumers are willing to give up.

Market effects

The Michael Porter invented "Porter's Five Forces" to analyse an industry's attractiveness and likely profitability. Alongside competitive rivalry, buyer power, supplier power and threat of new entry, Porter identifies the threat of substitution as one of the five important industry forces. The threat of substitution refers to the likelihood of customers finding alternative products to purchase. When close substitutes are available, customers can easily and quickly forgo buying a company's product by finding other alternatives. This can weaken a company's power which threatens long-term profitability. The risk of substitution can be considered high when:[21]

- Customers have slight switching costs between two available substitutes.

- The quality and performance offered by a close substitute are of a higher standard.

- Customers of a product have low loyalty towards the brand or product, hence being more sensitive to price changes.

Additionally substitute goods have a large impact on markets, consumer and sellers through the following factors:

- Markets characterised by close/perfect substitute goods experience great volatility in prices.[22] This volatility negatively impacts producers' profits, as it is possible to earn higher profits in markets with fewer substitute products. That is, perfect substitute results in profits being driven down to zero as seen in perfectly competitive markets equilibrium.

- As a result of the intense competition caused the availability of substitute goods, low quality products can arise. Since prices are reduced to capture a larger share of the market, firms try to reduce their utilisation of resources which in turn will reduce their costs.[22]

- In a market with close/perfect substitutes, customers have a wide range of products to choose from. As the number of substitutes increase, the probability that every consumer selects what is right for them also increases.[22] That is, consumers can reach a higher overall utility level from the availability of substitute products.

References

- "What are substitute goods? Definition and examples". Market Business News. Retrieved 2020-10-20.

- Nicholson, Walter; Snyder, Christopher (2008). Microeconomic Theory: Basic Principles and Extensions. Mason, Ohio: Thomson/South-Western. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-324-58507-0. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- D. Besanko, D. Dranove, S. Schaefer, M. Shanley (2013). Economics of Strategy. United States of America: John Wiley & Sons. p. 168. ISBN 9781118273630.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Curtis, Douglas; Irvine, Ian (2017). Macroeconomics: Theory, Models & Policy (Revision A ed.). Lyryx Learning. p. 67. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- "Other Demand Elasticities | Boundless Economics". courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 2020-10-13.

- "perfect substitute". Oxford Reference. Retrieved 2021-04-28.

- Besanko, David; Braeutigam, Ronald (2010-10-25). Microeconomics (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-470-56358-8. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- "Substitute goods - a key concept in Economics and Management". www.economicswebinstitute.org. Retrieved 2020-10-20.

- "What are substitute goods? Definition and examples". Market Business News. Retrieved 2020-10-13.

- Hayes, Adam. "How Substitutes Work". Investopedia. Retrieved 2020-10-21.

- Nicholson, Walter; Snyder, Christopher (2008). Microeconomic Theory: Basic Principles and Extensions. Mason, Ohio: Thomson/South-Western. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-324-58507-0. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- "utility - Gross substitutes vs. net substitutes". Economics Stack Exchange. Retrieved 2021-04-27.

- Huh, Young Eun; Vosgerau, Joachim; Morewedge, Carey K. (2016-06-01). "More Similar but Less Satisfying Comparing Preferences for and the Efficacy of Within- and Cross-Category Substitutes for Food". Psychological Science. 27 (6): 894–903. doi:10.1177/0956797616640705. ISSN 0956-7976. PMID 27142460. S2CID 4829178.

- Huh, Young Eun; Morewedge, Carey; Vosgerau, Joachim (2013). "Within-Category Versus Cross-Category Substitution in Food Consumption". ACR North American Advances. NA-41.

- "Unit Elastic Demand | Meaning, Example, Analysis, Conclusion". studyfinance.com. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- Bichler, Martin (2017). Market Design: A Linear Programming Approach to Auctions and Matching. Cambridge University Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-316-80024-9. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- Lordkipanidze, Revaz (2022-04-23). "Perfect Competition". Retrieved 2022-04-23.

- Hayes, Adam. "Understanding Perfect Competition". Investopedia. Retrieved 2020-10-21.

- "Putting Ads between Hardcovers to Reduce Prices and Raise Profits". Media Asia. 16 (3): 153. January 1989. doi:10.1080/01296612.1989.11727241. ISSN 0129-6612.

- Chappelow, Jim. "Monopolistic Competition Definition". Investopedia. Retrieved 2020-10-21.

- "Substitute Goods: Meaning, Elasticity, Examples". Penpoin. 2020-02-04. Retrieved 2021-04-28.

- "Substitute Products - Understanding the Impact of Substitute Products". Corporate Finance Institute. Retrieved 2020-10-01.