Periander

Periander (/ˌpɛriˈændər/; Greek: Περίανδρος; died c. 585 BC) was the Second Tyrant of the Cypselid dynasty that ruled over ancient Corinth. Periander's rule brought about a prosperous time in Corinth's history, as his administrative skill made Corinth one of the wealthiest city states in Greece.[1] Several accounts state that Periander was a cruel and harsh ruler, but others[2] claim that he was a fair and just king who worked to ensure that the distribution of wealth in Corinth was more or less even. He is often considered one of the Seven Sages of Greece, men of the 6th century BC who were renowned for centuries for their wisdom. (The other Sages were most often considered to be Thales, Solon, Cleobulus, Chilon, Bias and Pittacus.)[1]

| Periander | |

|---|---|

| Tyrant of Corinth | |

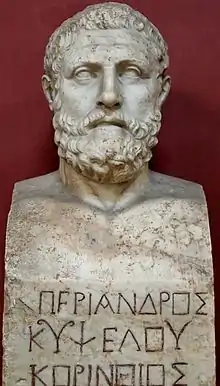

Periander, Roman copy after a Greek original of the 4th century BC, Vatican Museums. | |

| Reign | 627–585 BC |

| Predecessor | Cypselus |

| Successor | Psammetichus |

| Born | prior to 635 BC Corinth |

| Died | 585 BC Corinth |

| Consort | Lyside |

| Issue |

|

| Greek | Περίανδρος |

| House | Cypselid |

| Father | Cypselus |

| Mother | Cratea |

| Religion | Greek polytheism |

Life

Family

Periander was the second tyrant of Corinth[3] and the son of Cypselus, the founder of the Cypselid dynasty. Because of his father, he was called Cypselides (Κυψελίδης).[4] Cypselus’ wife was named Cratea. There were rumors that she and her son, Periander, slept together.[5] Periander married Lyside (whom he often referred to as Melissa), daughter of Procles and Eristenea of Epidaurus.[5] They had two sons: Cypselus, who was said to be weak-minded, and Lycophron, a man of intelligence.[5] According to the book Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, Periander, in a fit of rage, kicked his wife or threw her down a set of stairs so hard that she was killed.[5][6] Greek historian Herodotus has alluded to suggestions that Periander had defiled the corpse of his wife, employing a metaphor: "Periander baked his bread in a cold oven".[7] Grief for his mother and anger at his father drove Lycophron to take refuge in Corcyra.[6] When Periander was much older and looking to have his successor at his side, he sent for Lycophron.[5] When the people of Corcyra heard of this, they killed Lycophron rather than let him depart. The death of his son caused Periander to fall into a despondency that eventually led to his death.[5] Periander was succeeded by his nephew, Psammetichus, who ruled for just three years and was the last of the Cypselid tyrants.[8]

Rule

Periander built Corinth into one of the major trading centers in Ancient Greece.[3] He established colonies at Potidaea in Chalcidice and at Apollonia in Illyria,[3] conquered Epidaurus, formed positive relationships with Miletus and Lydia, and annexed Corcyra, where his son lived much of his life.[3] Periander is also credited with inventing a transport system, the Diolkos, across the Isthmus of Corinth. Tolls from goods entering Corinth's port accounted for nearly all the government revenues, which Periander used to build temples and other public works, and to promote literature and arts. He had the poet Arion come from Lesbos to Corinth for an arts festival in the city. Periander held many festivals and built many buildings in the Doric style. The Corinthian style of pottery was developed by an artisan during his rule.

Periander's style of leadership and politics was termed a 'tyranny'. Tyrants favored the poor over the rich, sometimes confiscating landlord's possessions and enacting laws that limited their privileges. They also started the construction of temples, ports and fortifications, and improved the drainage of the city and supply of water. Periander adopted measures that benefitted commerce.[2]

Writing and philosophy

Periander was said to be a patron of literature, who both wrote and appreciated early philosophy. He is said to have written a didactic poem 2,000 lines long.[5] In the Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, Diogenes Laërtius points out that writers disagree on who the Seven Sages are. It is posited that Periander tried to improve order in Corinth; although he appears on Diogenes Laërtius's list, his extreme measures and despotic gestures make him more suited to a list of famous tyrants than of wise men.[2]

Influences

Periander is referenced by many contemporaries in relation to philosophy and leadership. Most commonly he is mentioned as one of the Seven Sages of Ancient Greece, a group of philosophers and rulers from early Greece, but some authors leave him out of the list. In Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, Diogenes Laërtius, a philosopher of the 3rd century AD, lists Periander as one of these Seven Sages. Ausonius also refers to Periander as one of the Sages in his work The Masque of the Seven Sages.[9]

Some scholars have argued that the ruler named Periander was a different person from the sage of the same name. Diogenes Laërtius writes that "Sotion, and Heraclides, and Pamphila in the fifth book of her Commentaries say that there were two Perianders; the one a tyrant, and the other a wise man, and a native of Ambracia. Neanthes of Cyzicus makes the same assertion, adding, that the two men were cousins to one another. Aristotle says, that it was the Corinthian Periander who was the wise one; but Plato contradicts him."[10]

See also

References

- "Seven Wise Men of Greece". Columbia Encyclopedia (6 Copyright © 2023 ed.) – via www.infoplease.ocm.

- Gomez, Carlos (2019). The Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece. United Kingdom: Amber Books Ltd. pp. 89–92. ISBN 978-1-78274-762-8.

- "Periander". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, Cypsĕlus

- Laertius, Diogenes. "Life of Periander". Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2014-05-02.

- Gentleman of Cambridge (1731). The history of Periander, King of Corinth. printed: and sold by J. Roberts in Warwick-Lane.

- Herodotus The Histories, 5.92g

- "Corinth, Ancient". www.hellenicaworld.com.

- Ausonius. "The Masque of the Seven Sages".

- Pausanias. "Description of Greece".

External links

Quotations related to Periander at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Periander at Wikiquote Media related to Periander at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Periander at Wikimedia Commons Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 1:1. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 1:1. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.