Cliff swallow

The cliff swallow or American cliff swallow (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota) is a member of the passerine bird family Hirundinidae, the swallows and martins.[2] The generic name Petrochelidon is derived from the Ancient Greek petros meaning "rock" and khelidon "swallow", and the specific name pyrrhonota comes from purrhos meaning "flame-coloured" and -notos "-backed".[3]

| Cliff swallow | |

|---|---|

| |

| at Palo Alto Baylands NR, California, USA | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Hirundinidae |

| Genus: | Petrochelidon |

| Species: | P. pyrrhonota |

| Binomial name | |

| Petrochelidon pyrrhonota (Vieillot, 1817) | |

| |

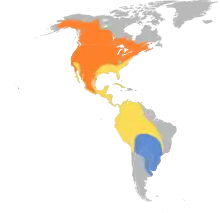

| Approximate distribution map

Breeding Migration Nonbreeding | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Petrochelidon lunifrons | |

Cliff swallows are extremely social songbirds that can be found in large nesting colonies reaching over 2,000 nests.[2][4][5] They are frequently seen flying overhead in large flocks during migration, gracefully foraging over fields for flying insects or perching tightly together on a wire preening under the sun.[4]

Cliff swallows build gourd-shaped nests made from mud with small entrance holes.[2][4][6] They build their nests tightly together, on top of one another, under bridges or alongside mountain cliffs.[2][4] Living in large populations, these aerial insectivores use extensive vocalizations to communicate warnings or food availability to the other individuals.[4]

Description

The cliff swallow's average body length is 13 cm (5.1 in), and they have short legs and small bills with relatively long pointed wings.[5][6] Adult cliff swallows have an overall dark brownish plumage covering both their back and wings, and they have a characteristic white forehead, rich red-coloured cheeks with a dark throat, basic white underparts and a buffy-coloured rump.[2][6] In good lighting conditions, their crowns and mantle feathers are iridescent.[2][5] The Northern population is slightly larger in body size and also differs in facial markings from the Mexican population of cliff swallows, which have a chocolate-brown patch on their foreheads.[2]

| Average Measurements[2][5][7] | |

|---|---|

| length | 5–6 in (130–150 mm) |

| weight | 19–31 g (0.67–1.09 oz) |

| wingspan | 11–13 in (280–330 mm) |

| wing | 105.5–111.5 mm (4.15–4.39 in) |

| tail | 47–51 mm (1.9–2.0 in) |

| culmen | 6.4–7.3 mm (0.25–0.29 in) |

| tarsus | 12–13 mm (0.47–0.51 in) |

.jpg.webp)

The male and female have identical plumage, therefore sexing them must be done through palpation of the cloaca.[2][4] During the breeding season, the males will have a harder cloaca that is more pronounced because the seminal vesicles are swollen.[4] In addition, during incubation females will lose feathers on their lower breast to create a warm patch for sitting on their eggs.[4] Cliff swallows are similar in body plumage colouring to the related barn swallow species but lack the characteristic fork-shaped tail of the barn swallow prominent during flight.[6] The cliff swallows have a square-shaped tail.[2][5][6]

Juvenile cliff swallows have an overall similar body plumage colouring to the adults, with paler tones.[2][4][6] The juveniles lack the iridescent adult plumages, and their foreheads and throats appear speckled white.[2][4][8] The juvenile cliff swallows’ white forehead and throat markings have high variance between unrelated individuals compared with those from the same clutch.[8] These distinctive white facial markings disappear during maturity following their complex-basic moult pattern, because their pre-formative plumage is different from the basic plumage.[2][8] The pre-formative facial plumage has been suggested as a possible way for parents nesting in large colonies to recognize their chicks.[4][8]

Taxonomy

The cliff swallow belongs to the largest order and dominant avian group – Passeriformes.[2][6][9] They are the perching birds, or the passerines.[9][10] All the bird species in this order have 4 toes, 3 pointing forward and one pointing backwards (anisodactylous), that enable them to perch with ease.[9][10] The sub-order that the cliff swallow belongs to is Oscines (or Passeri), for the songbirds.[9] The family that encompasses approximately 90 species of swallows and martins, Hirundinidae, includes birds that have small stream-lined bodies made for great agility and rapid flight.[11] Furthermore, those in the family Hirundinidae have short-flat bills for their largely insectivorous diets, small feet because they spend much of their time in flight and long wings for energy-efficient flight.[6][11]

There are 5 subspecies of cliff swallow distinguished on the basis of plumage colour, body size, and distribution – Petrochelidon pyrrhonota pyrrhonota, P. p. melanogaster, P. p. tachina, P. p. hypopolia, P. p. ganieri.[12] In addition, three core genera of hirundo were established on the basis of molecular studies: Hirundo sensu stricto, containing the barn swallow; Cecropis, containing the red-rumped swallow; and Petrochelidon, containing the cliff swallow.[2] The genetic tests deemed Petrochelidon and Cecropis sister to each other and both closest to Delichon, the house martins.[2] Finally, the cave swallow was identified as the nearest living relative in North America of the cliff swallow.[2] The cave swallow has a similar plumage to the cliff swallow; however, the former has a dark cap and pale throat, and also a much smaller distribution in North America, most likely due to a decline in suitable cave sites.[2]

Habitat and distribution

As their name suggests, throughout history the cliff swallows concentrated their nesting colonies along mountain cliffs, primarily by the western North American coast.[2] Today, with the development of highways, concrete bridges, and buildings this adaptable bird species is rapidly adjusting its common nesting sites, with populations expanding further east and building their mud nests on these concrete infrastructures.[2][4] Thus, the cliff swallow's breeding range includes large areas across Canada and the United States of America, excluding some Southern and Northern areas.[6][13] The majority of nesting colonies are situated in close proximity to fields, ponds, and other ecosystems that would hold a large variety of flying insect populations to sustain their energy requirements during the breeding season.[2][4]

The cliff swallows' wintering grounds have been recorded as South American countries, such as Southern Brazil, Uruguay, and parts of Argentina.[2][5][13] However, their behavior and populations have yet to be extensively studied on their wintering grounds leaving room for new information about this species.[4] The cliff swallows are long-distance day-migrants that generally travel along the North American coastlines.[5] The Eastern populations travel through Florida, and the Western populations through Mexico and Central America down to their destinations.[2][5][6] Flocks containing large numbers of cliff swallows have been recorded migrating together, but whether they stay together or disperse to different locations is unknown.[4]

Swallows of Capistrano

The cliff swallow is famous for their regular migration to San Juan Capistrano, California.[14] They nest at the church of Mission San Juan Capistrano, where their annual migration is culturally celebrated. A 1940 song by Leon René, When the Swallows Come Back to Capistrano, celebrates this event.

Behavior

Cliff swallows live in a colonial lifestyle during the breeding season, composed of a large number of pairs per nesting site.[2][4][5] This group-style life can present the birds with some benefits and disadvantages; valuable information can be shared through group learning about food location and habitat preferences, but it is also much easier to transmit parasites or diseases when living in close proximity.[2][4][15] The cliff swallows have an unusually large parasite community that includes ectoparasites, ticks, fleas and swallow bugs, among others.[2][4][5][15][16] These parasite infestations have been shown to negatively affect juvenile growth and developmental rates.[7][15][16]

Cliff swallows are socially monogamous, one pair will look after each nest, but many occurrences of sexual polygamy have been noted because of the varying genetics throughout the colony and within many individual nests.[2] Both the female and the male cliff swallows will contribute to the colony's genetic variability by performing various actions of brood-parasitism.[2][4][8][17] The cliff swallows have an “aggressive and fearless” personality in comparison to their relatives the barn swallows who were noted as being “timid and fearful”.[4]

Diet

The cliff swallows feed on a diet consisting of flying insects, particularly swarming species such as: flies, bees, lacewings, mayflies, butterflies, moths, grasshoppers, and damselflies.[4][5] The birds forage high (usually 50 m or higher) over fields or marshes, and tend to rely on bodies of water like ponds during bad weather with high winds.[2][4] These birds are day-hunters (diurnal), returning to their nesting sites at dusk, and are not very active during cold or rainy weather because of the low number of prey available.[4][7] Foraging behaviors related closely to their reproduction cycle; when the birds first arrive at the nesting site they will forage as far as 10 miles from the colony, in the hopes of increasing body fat reserves to prepare for cold-windy days and their energy extensive egg-laying stage.[2][4] When the swallows return to the nesting site at dusk, they often fly in a tightly coordinated flock overhead, in such close synchronization that they may appear as one large organism.[4][5] These large group formations are called creches.[5]

The cliff swallows' social behavior does not end with these “synchronized flying” displays; they use special vocalizations to advise other colony members of a good prey location where ample food is available.[4] It has been thought that colony sites located close to marshes would have larger quantities of insects to support big populations; however, there are equally large nesting colonies located at a great distance from marshes.[4]

Vocalisations

The social structure of these cliff swallow colonies has evolved a complex vocalisation system.[2][4][5] Five vocalisations have been identified, which are used by both juveniles and adults for different reasons.[2] These vocalisations are structurally similar across the age groups and can be described as begging, alarm, recognition, and squeak calls, all with some variations.[2] Juvenile cliff swallows are said to have established a unique call by the approximate age of 15 days, which allows the parents to identify their chick from others in the colony.[2][4]

The “squeak” call is of great interest to researchers because this is the special vocalisation made at a distance from the colony when a bird encounters a good foraging area.[4] When this call is heard, large groups of their colony "neighbours" will arrive at the location.[4] This "squeak" call is used greatly during bad weather conditions.[2][4] For this specific call, the cliff swallows are one of the few known vertebrates to make a “competitively disadvantageous” cue to their peers for food availability.[4]

Alarm calls are heard at the colony while the birds are flying over and around the colony entrance way, and serve as a signal of danger close to the nests. When this call is heard by the other colony members, a mass fleeing of birds out and away from their nests is observed.[4]

Reproduction

The breeding season of cliff swallows starts with the return of the birds from their wintering grounds. They usually arrive in large groups and start immediately to choose their nesting sites.[2][4] The cliff swallows have been observed to skip from one to five years between breeding at the same place to avoid parasite infestations, but some pairs will return annually to the same site.[4] Particularly for younger pairs, the size of the colony can affect their reproductive success, because they seem to rely on the valuable information that can be obtained from a large colony.[2][4] Older birds are usually found in smaller colonies and exhibit earlier nesting times, avoiding the parasite manifestation that comes with the hot mid-summer season.[4][15][16]

.jpg.webp)

Cliff swallows decide upon arrival at their nesting site whether they will fix a nest from the previous season or build a new nest.[2][4] Building a new nest may have the benefit of lower parasite numbers, but it is very energy expensive and time-consuming.[4][16] Further, taking the extra time to build a nest from scratch will mean reproducing later which could negatively affect their chicks’ survival.[2][4][16] Nests constructed with sticky clay can last a number of years and are further supported by the cliff swallows’ tier-stacking construction strategy.[2][4][5] Cliff swallows from the same colony socially collect mud for nest building, being seen converging at small areas together and then carrying globs of mud in their bills back to their nests.[4]

Each bird pair will have about 3–4 nestlings per brood; a clutch size of 4 has been identified as the most common and most successful.[17] The cliff swallows brood-parasitize neighboring nests, where the females may move their eggs into or lay their eggs in other nests.[2][5] The females who show intra-specific parasitism tend to have greater reproductive success than those that were brood-parasitized.[2][17] The “victims” of brood-parasitism must nurture more chicks with higher energy costs and decreased fitness because they are raising young that will not pass on their own genetic material.[17] The male cliff swallows will also take part in this gene-spread by mating with more than just one female, contributing to genetic variation throughout the colony.[2]

The nesting sites can be vulnerable to predation by other bird species, such as the house sparrow.[4][5] These birds will search a number of swallow nests for the perfect place to make their own nest, destroying numerous eggs in the process.[4] Nests, especially those at the periphery of colonies, are vulnerable to snake predation. Central nests are more coveted, have larger clutches, and are preferred for reuse in subsequent years [18]

Once the house sparrows pick their nest, they will bring in grass and other materials making it impossible for the cliff swallows to re-establish their place.[2][19] Thus, the colonies with house sparrow predation have an overall lower success rate and fewer previous-year nests being used.[19]

References

- BirdLife International (2016). "Petrochelidon pyrrhonota". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22712427A94333165. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22712427A94333165.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Brown, Charles R.; Brown, Mary B.; Pyle, Peter; Patten, Michael A. (2017). "Cliff Swallow (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota)". The Birds of North America Online. doi:10.2173/bna.cliswa.03. S2CID 83748545.

- Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 300, 327. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Brown, Charles R. (1998). Swallow summer. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803261457. OCLC 38438988.

- The Cornell Lab of Ornithology (2015). "Cliff Swallow". All About Birds. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- Sibley, David (2016). The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Eastern North America (Second ed.). New York: Borzoi Books – Knopf. ISBN 9780307957917. OCLC 945096007.

- Roche, Erin A.; Brown, Mary B.; Brown, Charles R. (December 2014). "The Effect of Weather on Morphometric Traits of Juvenile Cliff Swallows". Prairie Naturalist – University of Nebraska Lincoln. 46 (2): 76–87.

- Johnson, Allison E.; Freedberg, Steven (2014). "Variable facial plumage in juvenile Cliff Swallows: A potential offspring recognition cue?". The Auk. 131 (2): 121–128. doi:10.1642/AUK-13-127.1. ISSN 0004-8038.

- Edwards, Scott V.; Harshman, John (February 6, 2013). "Passeriformes. Perching Birds. Passerine Birds". The Tree of Life Web Project. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- Gill, Frank; Clench, Mary H.; Austin, Oliver L. (August 1, 2016). "Passeriform". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc.

- "Hirundinidae". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. July 21, 2011.

- Integrated Taxonomic Information System (October 7, 2017). "Petrochelidon pyrrhonota (Vieillot, 1817)". ITIS.

- "Cliff Swallow - eBird". ebird.org. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- Account, Master (2019-11-04). "San Juan Capistrano Swallows | SanJuanCapistrano.com". San Juan Capistrano. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- Brown, Charles R.; Brown, Mary Bomberger (2015-02-01). "Ectoparasitism shortens the breeding season in a colonial bird". Royal Society Open Science. 2 (2): 140508. Bibcode:2015RSOS....240508B. doi:10.1098/rsos.140508. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 4448812. PMID 26064606.

- Brown, Charles R.; Roche, Erin A.; O’Brien, Valerie A. (2015-02-01). "Costs and benefits of late nesting in cliff swallows". Oecologia. 177 (2): 413–421. Bibcode:2015Oecol.177..413B. doi:10.1007/s00442-014-3095-3. ISSN 0029-8549. PMID 25266478. S2CID 13863210.

- Brown, Charles R.; Brown, Mary B. (2004). "Mark–Recapture and Behavioral Ecology: a Case Study of Cliff Swallows". Animal Biodiversity and Conservation. 27 (1): 23–34.

- Osborne, S.; Leasure, D.; Huang, S.; Kannan, Ragupathy (2017-01-01). "Central Nests are Heavier and Have Larger Clutches than Peripheral Nests in Cliff Swallow (Petrochelidon pyrrohonota) Colonies". Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science. 71 (1): 206–208. doi:10.54119/jaas.2017.7132. ISSN 2326-0491. S2CID 52210939.

- Leasure, Douglas R.; Kannan, Ragupathy; James, Douglas A. (2010). "House Sparrows Associated with Reduced Cliff Swallow Nesting Success". The Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 122 (1): 135–138. doi:10.1676/09-061.1. JSTOR 40600386. S2CID 85866560.

Books

- Turner, Angela K.; Rose, Chris (1989). A Handbook to the Swallows and Martins of the World. Helm Identification Guides. Christopher Helm Publishers Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7470-3202-1.

External links

- "Cliff swallow media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Cliff swallow – Petrochelidon pyrrhonota – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Cliff swallow Species Account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Cliff swallow photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- eBird Interactive Species Map- Cliff swallow

- Birds of North America – Cliff swallow (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota)

- Cliff Swallow Vocalisations – Song and Calls

- Interactive range map of Petrochelidon pyrrhonota at IUCN Red List maps

- Cliff Swallow Project