Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad

The Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad (PW&B) was an American railroad that operated independently from 1836 to 1881. Headquartered in Philadelphia, it was greatly enlarged in 1838 by the merger of four state-chartered railroads in three Mid-Atlantic states to create a single line between Philadelphia and Baltimore.

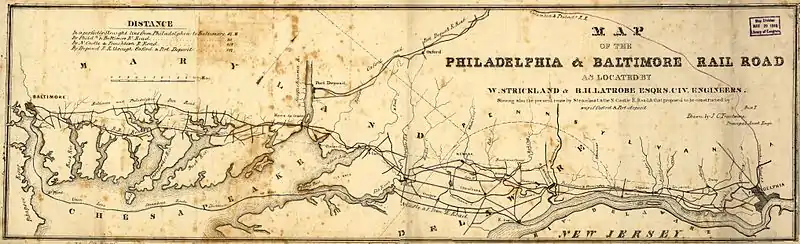

The rail lines of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad | |

Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad flatcars outside Gray's Ferry Tavern in southwest Philadelphia, c. 1870s | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Locale | Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Maryland |

| Dates of operation | 1836–1902 (purchased 1880 by Pennsylvania Railroad) |

| Predecessor |

|

| Successor | Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington Railroad (PB&W) - (1902-1976) |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Length | 669 mi (1,077 km)[1] |

In 1881, the PW&B was purchased by the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR), which was at the time the nation's largest railroad. In 1902, the PRR merged it into its Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington Railroad.

The right-of-way laid down by the PW&B line is still in use today as part of Amtrak's Northeast Corridor and the Maryland Department of Transportation's MARC commuter passenger system from Baltimore to Maryland's northeast corner. Freight is hauled on the route; formerly by the Conrail system and currently by Norfolk Southern.

History

19th century

On April 2, 1831, the General Assembly of Pennsylvania, seeking to improve transportation between Philadelphia and points south along the Atlantic coast and Eastern seaboard, chartered the Philadelphia and Delaware County Rail-Road Company. The legislature allotted $200,000 to build a rail line from America's largest city to the Delaware state line. In July 1835, surveyors began to look at possible routes, and in October, they reported that the best option, a 17-mile line, would cost $233,000 to build.

Further south, across the Mason–Dixon line, the Delaware and Maryland legislatures, were doing their part to create a rail link to Wilmington and Baltimore. On January 18, 1832, the State of Delaware chartered the Wilmington and Susquehanna Rail Road Company (W&S, $400,000) to build from Wilmington to the Maryland state line. On March 5, the State of Maryland chartered the Baltimore and Port Deposite Rail Road Company (B&PD) (with $1,000,000) to build from Baltimore northeast to the western bank of the Susquehanna River.[3] On March 12, the Delaware and Maryland Rail Road Company (D&M) was chartered for $3,000,000 to build from Port Deposit or any other point on the Susquehanna's eastern river bank north to the Delaware line.[4][5]

In 1835, the W&S hired architect/surveyor William Strickland to make a preliminary survey to the southwest between Wilmington and North East, Maryland.[6] That same year, the B&PD began operating trains between Baltimore harbor's basin at the present-day Inner Harbor waterfront and its Canton industrial, commercial and residential neighborhood to the southeast.[7]: 418n16 But Matthew Newkirk, who had invested $50,000 in the B&PD including funds borrowed from the United States Bank,[8] grew impatient. On Oct. 6, he wrote to the Company Board "demanding that Pres. Finley resign and be replaced by someone who will be more aggressive in collecting from delinquent subscribers and pushing project forward." As alternates, he suggests the noted lawyer, artist and civic activist, John H. B. Latrobe, brother of Chief Engineer Benjamin H. Latrobe, II (grandson of famous architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe), or Roswell L. Colt. Six days later, Colt became railroad line president, but his term lasted just five weeks; he was soon replaced by Lewis Brantz.[6]

In 1836, P&DC opened its first segment of track; saw its allowable expenditures upped by the State to $400,000; and changed its name, on March 14, to The Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad Company.[4][9] On July 4, the PW&B began building its bridge over the Schuylkill River, the most significant obstacle on its part of the route. The bridge would cross at Gray's Ferry Bridge, south of the city.[10] Meanwhile, on April 18, the D&M merged with the W&S, forming the Wilmington and Susquehanna Railroad Company.

Work also proceeded in Delaware and Maryland. By July 1837, there was continuous track from Baltimore to Wilmington, broken only by the wide Susquehanna River, which trains crossed by steam-powered ferryboats at Havre de Grace to Perryville.[10] That year, the railroad ordered seven 4-2-0 steam locomotives from Norris Locomotive Works; it ordered two more in or about 1840.[11]

On January 15, 1838, the PW&B opened service from Wilmington to Gray's Ferry, then a few miles south of Philadelphia's city limits. Passengers debarking at Gray's Ferry were taken by omnibus into the city.[12]

The disadvantages of tripartite ownership of the Philadelphia-Baltimore line became obvious, and the three remaining state-chartered railroads merged on February 12, 1838, to form the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad Company.[1] (The new company's name differed from its predecessor's in that "The" at the beginning of the titled name was not part of its formal incorporated name.[9])

Among the passengers that year was Frederick Douglass, a slave who escaped his Baltimore owner by boarding a PB&W train, perhaps at Canton or somewhere east of where the President Street Station would be built in 1849, and riding it northeast to Philadelphia. To avoid detention, Douglass, a future world-famous abolitionist, statesman, Federal official, orator and publisher, borrowed a "seaman's protection", a document obtained by his future wife, a free black woman, which was normally carried by free black sailors, of which there were many in the merchant fleets and the navy.[13] Later, the railroad would require black passengers to have "a responsible white person" sign a bond at the ticket office before allowing them to board.[14]

In December, the PB&W completed its Schuylkill bridge at Gray's Ferry. Named the "Newkirk Viaduct" after PW&B president Matthew Newkirk, it allowed trains to run from downtown Philadelphia to downtown Baltimore, with only the Susquehanna River steam railroad ferry interrupting the ride. (The railroad marked this achievement by erecting the Newkirk Viaduct Monument, a 15-foot marble obelisk designed by Thomas Ustick Walter, a future Architect of the Capitol.) That interruption was eventually bridged under pressure of the heavy traffic needs in 1864–5, the later days of the Civil War. After a disastrous storm damaged the new spans, reconstruction began anew and was completed by 1866.[4]

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) began using the tracks that same year to offer service northeast of Baltimore to Philadelphia.[15]

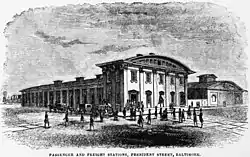

In Baltimore, the PW&B's terminus and business office sat at the southwest corner of President and Fleet Streets, east of the Jones Falls, the eventual future site of the President Street Station. The line ran east along Fleet Street, turned southeast onto Boston Street and ran along the waterfront past Canton before turning northeast and leaving the city limits, heading east, then northeast towards the Susquehanna.[13]

In Philadelphia, the line ended at Broad Street and Prime Avenue, which is now Washington Avenue, where it connected with the Southwark Rail-Road, built in 1835, to reach the Delaware River.

In 1839, the railroad's ticket agents advertised daily mail-and-passenger trains that left Baltimore's old original Pratt Street station at South Charles Street of the B&O (before 1857-65 construction of the now-famous Camden Street Station) at 9:30 a.m., stopped for lunch in Wilmington, Delaware, and reached the Market Street depot in Philadelphia at 4 p.m.[16]

In 1842, Newkirk resigned as PW&B president. He was replaced by Matthew Brooke Buckley (1794-1856),[17] who had become a PW&B board member on Jan. 10, 1842, and one week later had taken over leadership of one of the railroad's three executive committees, the Northern one.[18] As president, Buckley helped create the first telegraph line.

In 1844, Samuel F. B. Morse arranged for the B&O line to reach Washington, D.C. from Philadelphia and Baltimore by agreeing to allow the builder to use the PW&B right-of-way in exchange for the use of the communications equipment.[19]

On January 12, 1846, Buckley was replaced by Edward C. Dale,[20] a grandson of Richard Dale, one of the U.S. Navy's first commodores.[21]

Between 1846 and 1849, the railroad ordered five more locomotives, likely 4-4-0s, from the Norris Works.[11]

In February 1850, the PW&B improved its Baltimore terminus by completing erection of a new station, with a 208-foot (63 m) barrel-vaulted train shed.[7] Service onward to Washington, D.C., was facilitated by drawing the coaches by horse down Pratt Street to the B&O terminal, first at East Pratt and South Charles Streets, later after 1857, to the new Camden Street Station.[22]: 32 (In 1861, one week after the American Civil War began with the Confederate firings on Fort Sumter, in Charleston harbor, in South Carolina, an angry mob of Southern sympathizers attacked a trainload of future Union Army soldiers of the 6th Massachusetts volunteer state militia, joined in Philadelphia by the "Washington Brigade" of Pennsylvania state militia, heading to Washington, D.C. to protect the national capital and respond to President Abraham Lincoln's call for 75,000 troops and declaring a state of rebellion. Because locomotives were not allowed to transfer through the city possibly for fire safety reasons during their transfer: the "First Bloodshed" of this famous "Pratt Street Riot" set the nation irrevocably on the path to war.) Unwieldy as it was, the arrangement allowed the railroads to temporarily compete with the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad (renamed Pennsylvania Railroad after 1857) on routes going west from Philadelphia. By 1853, the Camden and Amboy Railroad and New Jersey Railroad were also part of this agreement, providing through service from New York City to the West.[23]

From 1863 to 1865, the railroad ordered ten 4-4-0 locomotives from the Norris Works.[11]

The PB&W also extended its reach into Delaware – on March 15, 1839, it bought the New Castle and Frenchtown Turnpike and Rail Road running from New Castle, Delaware, to Frenchtown, Maryland[24] – but it took 13 years to connect the line to the rest of the PW&B. The "New Castle and Wilmington Railroad" was chartered to do so, and opened in 1852. The line also provided a connection with the Delaware Railroad, which the PW&B took over and began to operate on January 1, 1857. In 1859, the NC&F was abandoned west of Porter, the junction with the Delaware Railroad. By 1866, these moves and others allowed the PW&B to dominate the Delmarva Peninsula rail market.[15]

In November 1866, the Susquehanna River was bridged at last by the PW&B Bridge, a 3,269-foot (996 m) wooden truss, finally creating a continuous rail connection between Philadelphia and Baltimore.

To avoid swampy areas and serve more populated ones, the PW&B built the Darby Improvement, which diverged from its existing main line just south of the Grays Ferry Bridge, passed through Darby, and rejoined it at Eddystone, just upriver from Chester.[9] The new inland track opened on November 18, 1872.[25] The PW&B dispensed with the 9.9-mile old alignment less than a year later, leasing it on July 1, 1873, to the Philadelphia and Reading Railway for 999 years with the stipulation that it would be used solely for freight.[26] (The Reading dubbed the line, along with some connecting track, its Philadelphia and Chester Branch;[27] southbound trains reached it via the Junction Railroad (jointly controlled by PW&B, Reading, and PRR) and continued on to the connecting Chester and Delaware River Railroad.)

The PW&B, which had competed so fiercely with the Pennsylvania, began to see their interests align. In 1873, the PRR opened the Baltimore and Potomac Rail Road (founded 1853, organized 1858), from Baltimore to Washington. The PW&B agreed to allow the PRR to use its track between Philadelphia and Baltimore, helping the PRR offer a shorter and more direct trip to Washington.

On May 15, 1877, the PW&B formally absorbed the New Castle and Frenchtown and New Castle and Wilmington railroads, forming a branch line from Wilmington to Rodney. On May 21, 1877, it then absorbed the Southwark railroad, extending its main line to the Delaware River waterfront.

In 1880, a conflict began between the PRR and the B&O, both of which operated over the PW&B. The B&O was working to reduce its reliance on PRR tracks; it had recently arranged to switch its Philadelphia-New York trains to the new Reading-controlled "Bound Brook Route," which had recently broken the PRR's monopoly on travel to New York via New Jersey. At the time, northbound B&O trains left the PW&B at Gray's Ferry Bridge in southwest Philadelphia and traveled over the Junction Railroad to Belmont, where they reached Reading rails and continued north. However, a mile of the Junction Railroad's track through Philadelphia was owned and used by the PRR, which showed great ingenuity in arranging delays to B&O trains.

The irate John W. Garrett (1820–84), the Civil War-era president of Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, decided to counter-attack by quietly buying out the PW&B, which would have cut off the Pennsylvania Railroad from its Baltimore & Potomac subsidiary. However, his agent encountered unexpected difficulties in buying up a majority of the stock at the price specified. Meanwhile, Garrett's maneuver became known to the PRR, which quickly bought out a majority of the stock at a somewhat higher price, preemptively taking control of the PW&B. Garrett and the Baltimore and Ohio were forced later to construct an independent separate northeast line to Philadelphia, the Baltimore and Philadelphia Railroad, while paying the PRR substantial fees to continue service further north to New York City over their lines. The new line opened in 1886; the Reading also used it to avoid the Junction Railroad.

A number of branches were built, bought and sold from 1881 to 1891, as described below. In 1895, the main line was realigned and straightened at Naaman's Creek in Delaware. The old line would become sidings for Claymont Steel.

The PRR's Baltimore and Potomac Rail Road was formally leased to the PW&B on November 1, 1891.

The Elkton and Middletown Railroad, opened in 1895, was planned as a cutoff between the main line at Elkton, Maryland, and the Delaware Railroad at Middletown, Delaware. However, only a short piece of track, serving industries in Elkton, was ever constructed. It was consolidated into the Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington Railroad on September 15, 1916.

An 1895 historian of the PRR had this to say about the significance of the PW&B, which it had acquired and gained control of fourteen years before:

An important constituent of a great North and South line of transportation, it challenges ocean competition and carries on its rails not only statesmen and tourists but a valuable interchange of products between different lines of latitude. As a military highway, it is of the greatest strategic importance to the national, industrial, and commercial capitals – Washington, Philadelphia and New York. It presents some of the very best transportation facilities to the commerce of the cities after which it is named and could not be obliterated from the railroad map of the United States without materially disturbing its harmony.[28]

20th century

The PW&B merged with the Baltimore and Potomac on November 1, 1902, to form the Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington Railroad.

Branches

- Southwark

- 60th Street/Chester: Built in 1918, it stretched 4.5 miles (7.2 km) from South 58th Street in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to Hog Island, Pennsylvania.

- South Chester

- Edgemoor

- Augustine Mill: Also called the Brandywine Branch, it was built in 1882 from Landlith north along the Brandywine Creek to reach the Augustine Mills of the Jessup & Moore Paper Company, and was later extended further north to serve the Kentmere and Rockford Mills of Joseph Bancroft & Sons.

- Shellpot: Also called the Shellpot Cutoff, it was built in 1888 from Edgemoor (near the crossing of the Shellpot Creek) around the south side of Wilmington to a point on the main line between Wilmington and Newport. It served as a freight bypass, to avoid what was then street running on the main line through Wilmington.

- Delaware Branch: Formed from the old New Castle & Frenchtown and New Castle & Wilmington trackage between Wilmington and Rodney, via New Castle. It was sold to the Delaware Railroad in 1891.

- New Castle Cut-off: Built in 1888 from a point on the Shellpot Branch just across the Christina River from Cherry Island, south to New Castle and a connection with the Delaware Branch. It was sold with the Delaware Branch to the Delaware Railroad in 1891.

- Delaware City: Sold by the Newark and Delaware City Railroad to the PW&B in 1881. It ran south and east from the main line at Newark to Delaware City.

- Port Deposit: Built in 1866 up the Susquehanna River from Perryville to the river town of Port Deposit. In 1893, it was sold to the Columbia and Port Deposit Railway, also PRR-controlled, which connected with it at Port Deposit.

- Baltimore Union

See also

References

- Poor's Manual of the Railroads of the United States. Vol. 33. New York: H.V. & H.W. Poor. 1900. p. 703.

- "On the Road: Sprouts Farmers Market, Philadelphia". 14 April 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- Maryland General Assembly. Chapter 188 of the 1831 Session Laws of Maryland.

- Dare, Charles P. (1856). Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad Guide: Containing a Description of the Scenery, Rivers, Towns, Villages, and Objects of Interest Along the Line of Road : Including Historical Sketches, Legends, &c. Philadelphia: Fitzgibbon & Van Ness. pp. 142.

- Maryland General Assembly. Chapter 296 of the 1831 Session Laws of Maryland.

- "1835 (June 2004 Edition)" (PDF). PRR CHRONOLOGY. The Pennsylvania Railroad Technical & Historical Society. June 2004. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- Dilts, James D. (1996). The Great Road: The Building of the Baltimore and Ohio, the Nation's First Railroad, 1828–1853. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2629-0.

- "The Railroads: 1883 account of he PW&B and monument". St. Louis Globe-Democrat. 1883-12-03. p. 6. Retrieved 2022-04-30.

- Netzlof, Robert T. (7 March 2001). "Corporate Genealogy Philadelphia, Baltimore & Washington". Robert T. Netzlof. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- Albert J. Churella (2012). The Pennsylvania Railroad, Volume 1: Building an Empire, 1846-1917, Volume 1. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 976. ISBN 9780812243482.

- White, John H. (1984). "Once the Greatest of Builders: The Norris Locomotive Works". Railroad History (150): 17–86. ISSN 0090-7847. JSTOR 43521008.

- Fisher, Chas. E. (1930). "The Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore Railroad Company". The Railway and Locomotive Historical Society Bulletin (21): 5–34. ISSN 0033-8842. JSTOR 43519569.

- Chalkley, Tom (March 15, 2000). "NATIVE SON: On the Trail of Frederick Douglass in Baltimore". Baltimore City Paper. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- "Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad. Notice to Colored people". New York Public Library Digital Collections. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. August 22, 2005. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- Harwood, Jr., Herbert H. (2005). "Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore Railroad". Maryland Online Encyclopedia. Maryland Historical Society. Archived from the original on 2008-07-20.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Crawford, A., agent (Feb 9, 1839). "Railroad to Philadelphia". American & Commercial Daily Advertiser. p. 4. Retrieved September 30, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jordan, John W., editor (1911). Colonial And Revolutionary Families Of Pennsylvania: Genealogical and Personal Memoirs: Vol. 1. Genealogical Publishing Com. ISBN 9780806352398.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "1842 (May 2004 Edition)" (PDF). PRR CHRONOLOGY. The Pennsylvania Railroad Technical & Historical Society. May 2004. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- Schwantes, Benjamin Sidney Michael (2009). Fallible Guardian: The Social Construction of Railroad Telegraphy in 19th-century America. ISBN 9780549924975. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- "1846 (April 2005 Edition)" (PDF). PRR CHRONOLOGY. The Pennsylvania Railroad Technical & Historical Society. April 2005. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- "Guide to the Dale Family Papers, 1749-1937". Naval Academy Library. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- Harwood, Herbert H. Jr. (1994). Impossible Challenge II: Baltimore to Washington and Harpers Ferry from 1828 to 1994. Baltimore: Barnard, Roberts. ISBN 0-934118-22-1.

- Baer, Christopher (March 2005). "1853 (March 2005 edition)" (PDF). PRR CHRONOLOGY. Philadelphia Chapter Pennsylvania Railroad Technical & Historical Society. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- "1839 (June 2004 Edition)" (PDF). PRR CHRONOLOGY. The Pennsylvania Railroad Technical & Historical Society. June 2004. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- Broomall, John M. (1872). "History of Chester, PA." Delaware River and West Jersey Railroad Commercial Directory. pp. 93-96.

- Morlok, Edward K., University of Pennsylvania (2005). "First Permanent Railroad in the U.S. and Its Connection to the University of Pennsylvania." Archived 2005-04-02 at the Wayback Machine Transportation Data. Accessed 2013-04-23.

- The Railway World, Volume 6 (1880)

- Wilson, William Bender (1895). History of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company with Plan of Organization, Portraits of Officials and Biographical Sketches. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: Henry T. Coates & Company. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

External links

- Christopher Baer's PRR Chronology, hosted by The Pennsylvania Railroad Technical & Historical Society

- Railroad History Database

- PRR Corporate History

- Data visualization of 1857 passenger traffic from various PW&B stations

- 1949 map of PB&W lines in 1881

- William Strickland's 1835 report on the feasibility of the Wilmington & Susquehanna route

- Photo of late-1800s PW&B baggage tag

Annual reports

- First Annual Report of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Rail Road Company ...: 1838-1840:Google, Hathitrust

- Organization of the United Companies Under the Name of Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Rail Road Company with Articles of Union

- The Sixth Annual Report of the Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore Railroad Company (1844)

- 35th through 48th Annual Report of the President and Directors of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Rail Road Company (1872–85)

- Fifty-Sixth Annual Report Of The Philadelphia Wilmington And Baltimore Railroad Company (1893)