Phil Spector

Harvey Phillip Spector (December 26, 1939 – January 16, 2021) was an American record producer and songwriter, best known for his innovative recording practices and entrepreneurship in the 1960s, followed decades later by his two trials and conviction for murder in the 2000s. Spector developed the Wall of Sound, a production style that is characterized for its diffusion of tone colors and dense orchestral sound, which he described as a "Wagnerian" approach to rock and roll. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in pop music history[2][3] and one of the most successful producers of the 1960s.[4]

Phil Spector | |

|---|---|

Spector in 1965 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Harvey Philip Spector[1] |

| Also known as | Phil Harvey |

| Born | December 26, 1939 New York City, U.S. |

| Origin | Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Died | January 16, 2021 (aged 81) French Camp, California, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupation(s) |

|

| Years active | 1958–2009 |

| Labels | |

| Formerly of |

|

| Spouse(s) | Annette Merar

(m. 1963; div. 1966)Rachelle Short

(m. 2006; div. 2018) |

| Website | philspector |

Born in the Bronx, Spector moved to Los Angeles as a teenager and began his career in 1958 as a founding member of The Teddy Bears, for whom he penned "To Know Him Is to Love Him", a U.S. number-one hit. In 1960, after working as an apprentice to Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, Spector co-founded Philles Records, and at the age of 21 became the youngest-ever U.S. label owner at the time.[5] Dubbed the "First Tycoon of Teen",[6][7] Spector came to be considered the first auteur of the music industry for the unprecedented control he had over every phase of the recording process.[8] He produced acts such as The Ronettes, The Crystals, and Ike & Tina Turner, and typically collaborated with arranger Jack Nitzsche and engineer Larry Levine. The musicians from his de facto house band, later known as "The Wrecking Crew", rose to industry fame through his hit records.

In the early 1970s, Spector produced the Beatles' Let It Be and several solo records by John Lennon and George Harrison. By the mid-1970s Spector had produced eighteen U.S. Top 10 singles for various artists. His chart-toppers included the Righteous Brothers' "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'", the Beatles' "The Long and Winding Road", and Harrison's "My Sweet Lord". Spector helped establish the role of the studio as an instrument,[9] the integration of pop art aesthetics into music (art pop),[10] and the genres of art rock[11] and dream pop.[12] His honors include the 1973 Grammy Award for Album of the Year for co-producing Harrison's Concert for Bangladesh, a 1989 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and a 1997 induction into the Songwriters Hall of Fame.[13] In 2004, Spector was ranked number 63 on Rolling Stone's list of the greatest artists in history.[14]

Following one-off productions for Leonard Cohen (Death of a Ladies' Man), Dion DiMucci (Born to Be with You), and the Ramones (End of the Century), from the 1980's on Spector remained largely inactive amid a lifestyle of seclusion, drug use, and increasingly erratic behavior.[15] In 2009, after two decades in semi-retirement,[16] he was convicted of the 2003 murder of actress Lana Clarkson and sentenced to 19 years to life in prison, where he died in 2021.

Biography

1939–1959: Background and the Teddy Bears

Harvey Philip Spector was born on December 26, 1939.[17][nb 1] He later added a second "l" to his middle name, which he preferred over "Harvey".[19] His parents were Benjamin (1903–1949)[20] and Bertha (1911–1995)[21] Spector, a first-generation immigrant Russian-Jewish family in the Bronx, New York City.[22][23] Bertha had been born in France to Russian migrants George and Clara Spektor, who brought her to America in 1911 aged 9 months,[18] while Benjamin was born as Baruch (later changed to Benjamin) in the Russian Empire to George and Bessie Spektus or Spektres, and brought to America by his parents in 1913 aged 10.[24] Both families anglicized their last names to "Spector" on their naturalization papers, both of which were witnessed by the same man, Isidore Spector.[18] The similarities in name and background of the grandfathers led Spector to believe that his parents were first cousins. He had a sister named Shirley, who was six years his senior; she died in 2004 in Hemet, California, at the age of 70.[25]

In April 1949, Spector's father, who was deeply in debt, committed suicide; on his gravestone were inscribed the words "Ben Spector. Father. Husband. To Know Him Was To Love Him".[26][27] In 1953, Spector's mother moved the family to Los Angeles where she found work as a seamstress.[28] Spector attended John Burroughs Junior High School (now John Burroughs Middle School) on Wilshire Boulevard, then in 1954 attended Fairfax High School.[29] Having learned to play guitar, Spector performed "Rock Island Line" in a talent show at Fairfax High.[30] He joined a loose-knit community of aspiring musicians, including Lou Adler, Bruce Johnston, Steve Douglas, and Sandy Nelson.[31] Spector formed a group, the Teddy Bears, with Nelson and three other friends, Marshall Leib, Harvey Goldstein and Annette Kleinbard.[32][33]

During this period, record producer Stan Ross—co-owner of Gold Star Studios in Hollywood—began to tutor Spector in record production and exerted a major influence on Spector's production style. In 1958, the Teddy Bears recorded the Spector-penned "Don't You Worry My Little Pet", and then signed a two to three singles recording deal with Era Records, with the promise of more if the singles did well.[32][33]

At their next session, they recorded another song Spector had written—this one inspired by the epitaph on Spector's father's tombstone. Released on Era's subsidiary label, Dore Records, "To Know Him Is to Love Him" reached number one on Billboard Hot 100 singles chart on December 1, 1958, selling over a million copies by year's end.[34] Following the success of their debut, the group signed with Imperial Records.[35] Their next single, "I Don't Need You Anymore", reached number 91. They released several more recordings, including an album, The Teddy Bears Sing!, but failed to reach the top 100 in US sales. The group disbanded in 1959.[34]

1959–1962: Early production work, Philles Records, and the Crystals

While recording the Teddy Bears' album, Spector met Lester Sill, a former promotion man who was a mentor to Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller.[36] Sill and his partner, Lee Hazlewood supported Spector's next project, the Spectors Three. In 1960, Sill arranged for Spector to work as an apprentice to Leiber and Stoller in New York.[36] Spector co-wrote the Ben E. King Top 10 hit "Spanish Harlem" with Leiber and also worked as a session musician, playing the guitar solo on the Drifters' song "On Broadway".[37]

Spector's first true recording artist and project as producer was Ronnie Crawford. Spector's production work during this time included releases by LaVern Baker, Ruth Brown, and Billy Storm, as well as the Top Notes' original recording of "Twist and Shout".[38] Leiber and Stoller recommended Spector to produce Ray Peterson's "Corrine, Corrina", which reached number 9 in January 1961. Later, he produced another major hit for Curtis Lee, "Pretty Little Angel Eyes", which made it to number 7. Returning to Hollywood, Spector agreed to produce one of Sill's acts. After both Liberty Records and Capitol Records turned down the master of "Be My Boy" by the Paris Sisters, Sill formed a new label, Gregmark Records, with Lee Hazlewood, and released it. It reached only number 56, but the follow-up, "I Love How You Love Me", was a hit, reaching number 5.[39]

In late 1961, Spector formed a record company with Sill, who by this time had ended his business partnership with Hazlewood. Philles Records combined the first names of its two founders.[40] Through Hill and Range Publishers, Spector found three groups he wanted to produce: the Ducanes, the Creations, and the Crystals. The first two signed with other companies, but Spector managed to secure the Crystals for his new label. Their first single, "There's No Other (Like My Baby)" was a success, hitting number 20. Their next release, "Uptown", made it to number 13.[41]

Spector continued to work freelance with other artists. In 1962, he produced "Second Hand Love" by Connie Francis, which reached No. 7.[42] Ahmet Ertegun of Atlantic paired Spector with future Broadway star Jean DuShon for "Talk to Me", the B-side of which was "Tired of Trying", written by DuShon.

1962–1965: Bob B. Soxx & the Blue Jeans, the Ronettes, and the Righteous Brothers

In 1962, Spector briefly took a job as an A&R producer for Liberty Records.[43] It was while working at Liberty that he heard a song written by Gene Pitney, for whom he had produced a number 41 hit, "Every Breath I Take", a year earlier. "He's a Rebel" was due to be released on Liberty by Vikki Carr, but Spector rushed into Gold Star Studios and recorded a cover version using Darlene Love and the Blossoms on lead vocals. The record was released on Philles, attributed to the Crystals, and quickly rose to the top of the charts.

By the time "He's a Rebel" went to number 1, Lester Sill was out of the company, and Spector had Philles all to himself. He created a new act, Bob B. Soxx & the Blue Jeans, featuring Darlene Love, Fanita James (a member of the Blossoms), and Bobby Sheen, a singer he had worked with at Liberty. The group had hits with "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah" (number 8), "Why Do Lovers Break Each Other's Heart" (number 38), and "Not Too Young to Get Married" (number 63). Spector also released solo material by Darlene Love in 1963. In the same year, he released "Be My Baby" by the Ronettes, which went to number 2.

The first time Spector put the same amount of effort into an LP as he did into 45s was when he utilized the full Philles roster and the Wrecking Crew to make what he felt would become a hit for the 1963 Christmas season. A Christmas Gift for You from Philles Records was released a few days after the assassination of President Kennedy in November 1963.[44]

On September 28, 1963, the Ronettes appeared at the Cow Palace, near San Francisco. Also on the bill were the Righteous Brothers. Spector, who was conducting the band for all the acts, was so impressed with Bill Medley and Bobby Hatfield that he bought their contract from Moonglow Records and signed them to Philles. In early 1965, "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" became the label's second number 1 single. Three more major hits with the duo followed: "Just Once in My Life" (number 9), "Unchained Melody" (number 4, originally the B-side of "Hung on You"), and "Ebb Tide" (number 5). Despite having hits, he lost interest in producing the Righteous Brothers and sold their contract and all their master recordings to Verve Records. However, the sound of the Righteous Brothers' singles was so distinctive that the act chose to replicate it after leaving Spector, notching a second number 1 hit in 1966 with the Bill Medley–produced "(You're My) Soul and Inspiration".[45]

During this period, Spector formed another subsidiary label, Phi-Dan Records, partly created to keep promoter Danny Davis occupied. The label released singles by artists including Betty Willis, the Lovelites, and the Ikettes. None of the recordings on Phi-Dan were produced by Spector.[46]

The recording of "Unchained Melody", credited on some releases as a Spector production although Medley has consistently said he produced it originally as an album track,[47] had a second wave of popularity 25 years after its initial release, when it was featured prominently in the 1990 hit movie Ghost. A re-release of the single re-charted on the Billboard Hot 100, and went to number one on the Adult Contemporary charts. This also put Spector back on the U.S. Top 40 charts for the first time since his last appearance in 1971 with John Lennon's "Imagine", though he did have UK top 40 hits in the interim with the Ramones.[48]

1966–1969: Ike & Tina Turner and hiatus

Spector's final signing to Philles was the husband-and-wife team of Ike & Tina Turner in April 1966.[49][50] Spector considered their single "River Deep – Mountain High" his best work,[51] but it failed to reach any higher than number 88 in the United States. The record, which actually featured Tina Turner without Ike Turner, was successful in Britain, reaching number 3.

Spector released another single by Ike & Tina Turner, "I'll Never Need More Than This", while negotiating a deal to move Philles to A&M Records in 1967.[52] The deal did not materialize,[53] and Spector subsequently lost enthusiasm for his label and the recording industry. Already something of a recluse, he withdrew temporarily from the public eye, marrying Veronica "Ronnie" Bennett, lead singer of the Ronettes, in 1968. Spector emerged briefly for a cameo as himself in an episode of I Dream of Jeannie (1967) and as a drug dealer in the film Easy Rider (1969).[54]

In 1969, Spector made a brief return to the music business by signing a production deal with A&M Records. A Ronettes single, "You Came, You Saw, You Conquered" flopped, but Spector returned to the Hot 100 with "Black Pearl", by Sonny Charles and the Checkmates, Ltd., which reached number 13.[55]

1970–1973: Comeback and Beatles collaborations

In early 1970, Allen Klein, the new manager of the Beatles, brought Spector to England.[56] After impressing with his production of John Lennon's solo single "Instant Karma!", which went to number 3,[57] Spector was invited by Lennon and George Harrison to take on the task of turning the Beatles' abandoned Let It Be recording sessions into a usable album.[58] He went to work using many of his production techniques, making significant changes to the arrangements and sound of some songs.[59] Released a month after the Beatles' break-up, the album topped the U.S. and UK charts. It also yielded the number 1 U.S. single "The Long and Winding Road".[60] Spector's overdubbing of "The Long and Winding Road" infuriated its composer, Paul McCartney.[59] Several music critics also maligned Spector's work on Let It Be; he later attributed this partly to resentment that an American producer appeared to be "taking over" such a popular English band.[60] Lennon defended Spector, telling Jann Wenner of Rolling Stone: "he was given the shittiest load of badly recorded shit, with a lousy feeling toward it, ever. And he made something out of it. He did a great job."[61]

For Harrison's multiplatinum album All Things Must Pass (number 1, 1970), Spector helped provide a symphonic ambience,[62] although his health issues meant that after recording the basic tracks, he was absent from the project until the mixing stage.[63] Rolling Stone's reviewer lauded the album's sound, calling it "Wagnerian, Brucknerian, the music of mountain tops and vast horizons".[64] The triple LP yielded two major hits:[65] "My Sweet Lord" (number 1) and "What Is Life" (number 10). That same year, Spector co-produced Lennon's Plastic Ono Band (number 6), a stark-sounding album devoid of any Wall of Sound extravagance.[66] Through Harrison, he also produced the debut single by Derek and the Dominos, "Tell the Truth", but the band disliked the sound and had the record withdrawn.[67]

Spector was made head of A&R for Apple Records.[66] He held the post for only a year, during which he co-produced Lennon's 1971 single "Power to the People" (number 11) and his chart-topping album Imagine. The album's title track hit number 3. With Harrison, Spector co-produced Harrison's "Bangla Desh" (number 23)—rock's first charity single[68]—and wife Ronnie Spector's "Try Some, Buy Some" (number 77).[69] The latter was recorded for Ronnie's intended solo album on Apple Records, a project that stalled due to the same erratic, alcohol-fueled behavior from Spector that had hindered work on All Things Must Pass.[69][70] Spector was convinced that the Harrison-written single would be a major hit,[71] and its poor commercial performance was one of the biggest disappointments of his career.[72][nb 2]

That same year Spector oversaw the live recording of the Harrison-organized Concert for Bangladesh shows in New York City, which resulted in the number 1 triple album The Concert for Bangladesh.[75] The album won the "Album of the Year" award at the 1973 Grammys. Despite being recorded live, Spector used up to 44 microphones simultaneously to create his trademark Wall of Sound.[76][77] Following Harrison's death in 2001, Spector said that the most creative period of his career was when he worked with Lennon and Harrison in the early 1970s, and he believed that this was true of Lennon and Harrison also, despite their achievements with the Beatles.[78]

Lennon retained Spector for the 1971 Christmas single "Happy Xmas (War Is Over)" and the poorly reviewed 1972 album Some Time in New York City (number 48), both collaborations with Yoko Ono. In late 1972, Apple reissued Spector's A Christmas Gift for You from Philles Records (as Phil Spector's Christmas Album),[69] bringing the recordings the commercial success and critical recognition that had originally eluded the 1963 release.[79] Lennon and Ono's "Happy Xmas" single similarly stalled in sales upon its initial release, but later became a fixture on radio station playlists around Christmas.[80]

Harrison and Spector started work on Harrison's Living in the Material World album in October 1972, but Spector's unreliability soon led to Harrison dismissing him from the project.[81] Harrison recalled having to climb down into Spector's central London hotel room from the roof to get him to attend the sessions, and that his co-producer would then need "eighteen cherry brandies before he could get himself down to the studio".[82][nb 3]

In late 1973, Spector produced the initial recording sessions for what became Lennon's 1975 covers album Rock 'n' Roll (number 6).[83] The sessions were held in Los Angeles, with Lennon allowing Spector free rein as producer for the first time,[84] but were characterized by substance abuse and chaotic arrangements.[85] Amid the party atmosphere, Spector brandished his handguns and at one point fired a shot while Lennon was recording.[86][nb 4] In December, Lennon and Spector abandoned the collaboration.[88] Since the studio time had been booked by his production company, Spector withheld the tapes until June the following year, when Lennon reimbursed him through Capitol Records.[87]

1974–1980: Near-fatal accident, Warner-Spector Records, Leonard Cohen, and the Ramones

As the 1970s progressed, Spector became increasingly reclusive. The most probable and significant reason for his withdrawal, according to biographer Dave Thompson, was that in 1974 he was seriously injured when he was thrown through the windshield of his car in a crash in Hollywood.[89] Spector was almost killed, and it was only because the attending police officer detected a faint pulse that Spector was not declared dead at the scene. He was admitted to the UCLA Medical Center on the night of March 31, suffering serious head injuries that required several hours of surgery, with over 300 stitches to his face and more than 400 to the back of his head.[90] His head injuries, Thompson suggests, were the reason that Spector began his habit of wearing outlandish wigs in later years.[91]

He established the Warner-Spector label with Warner Bros. Records, which undertook new Spector-produced recordings with Cher, Darlene Love, Danny Potter, and Jerri Bo Keno, in addition to several reissues. A similar relationship with Britain's Polydor Records led to the formation of the Phil Spector International label in 1975. When the Cher and Keno singles (the latter's recordings were only issued in Germany) foundered on the charts, Spector released Dion DiMucci's Born to Be with You to little commercial fanfare in 1975; largely produced and recorded by Spector in 1974, it was subsequently disowned by the singer. In the 1990s and 2000s, the album enjoyed a resurgence among the indie rock cognoscenti.[92] The majority of Spector's classic Philles recordings had been out of print in the U.S. since the original label's demise, although Spector had released several Philles Records compilations in Britain. Finally, he released an American compilation of his Philles recordings in 1977, which put most of the better-known Spector hits back into circulation after many years.

Spector began to reemerge later in the decade, producing and co-writing a controversial 1977 album by Leonard Cohen, titled Death of a Ladies' Man. This angered many devout Cohen fans who preferred his stark acoustic sound to the orchestral and choral wall of sound that the album contains. The recording was fraught with difficulty. After Cohen had laid down practice vocal tracks, Spector mixed the album in studio sessions, rather than allowing Cohen to take a role in the mixing, as Cohen had previously done.[90] Cohen remarked that the result is "grotesque", but also "semi-virtuous"—for many years, he included a reworked version of the track "Memories" in live concerts. Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsberg also participated in the background vocals on "Don't Go Home with Your Hard-On".[93]

Spector also produced the much-publicized Ramones album End of the Century in 1979. As with his work with Leonard Cohen, End of the Century received criticism from Ramones fans who were angered over its radio-friendly sound. However, it contains some of the best known and most successful Ramones singles, such as "Rock 'n' Roll High School", "Do You Remember Rock 'n' Roll Radio?", and their cover of a previously released Spector song for the Ronettes, "Baby, I Love You".[nb 5] Guitarist Johnny Ramone later commented on working with Spector on the recording of the album, "It really worked when he got to a slower song like "Danny Says"—the production really worked tremendously. For the harder stuff, it didn't work as well."[94]

Rumors circulated for years that Spector had threatened members of the Ramones with a gun during the sessions. Dee Dee Ramone claimed that Spector once pulled a gun on him when he tried to leave a session.[95] Drummer Marky Ramone recalled in 2008, "They [guns] were there but he had a license to carry. He never held us hostage. We could have left at any time."[96][97]

1981–2003: Inactivity

Spector remained inactive throughout most of the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s. In early 1981, shortly after the death of John Lennon, he temporarily re-emerged to co-produce Yoko Ono's Season of Glass.[98]

In 1989, Tina Turner inducted Spector into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a non-performer.[99] Rolling Stone reported, "Spector hit the stage bopping madly to the strains of the Ronettes' "Be My Baby", flanked by three beefy bodyguards who practically elbowed Tina out of the way. He mumbled a few incoherent words about George H. W. Bush and the presidential inauguration, and then his bodyguards carried him away again."[100] He was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1997 and he received the Grammy Trustees Award in 2000.[13][101]

In 1994, Spector wrote a letter to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's nominating committee to oppose the Ronettes being considered for induction. He argued that the group was not a proper recording act and did not contribute enough to music to merit an induction.[102] The Ronettes were eventually inducted into the Hall, but not until 2007.[102]

He attempted to work with Céline Dion on her album Falling into You but fell out with her production team.[103] His last released project was Silence Is Easy by Starsailor, in 2003. He was originally supposed to produce the entire album, but was fired owing to personal and creative differences. One of the two Spector-produced songs on the album, the title track, was a UK top 10 single (the other single being "White Dove").[104]

2003–2021: Clarkson murder and imprisonment

On February 3, 2003, Spector shot actress Lana Clarkson in the mouth while in his mansion (the Pyrenees Castle) in Alhambra, California. Her body was found slumped in a chair with a single gunshot wound to her mouth.[105] Spector told Esquire in July 2003 that Clarkson's death was an "accidental suicide" and that she "kissed the gun".[106] The emergency call from Spector's home, made by Spector's driver, Adriano de Souza, quotes Spector as saying, "I think I killed somebody."[106] De Souza added that he saw Spector come out of the back door of the house with a gun in his hand.[106]

Spector remained free on $1 million bail while awaiting trial.[107] In the meantime, Spector produced singer-songwriter Hargo Khalsa's track (known professionally as Hargo) "Crying for John Lennon", which originally appears on Hargo's 2006 album In Your Eyes.[108] On a visit to Spector's mansion for an interview for the Lennon tribute film Strawberry Fields, Hargo played Spector the song and asked him to produce it.[109]

On March 19, 2007, Spector's murder trial began. Presiding Judge Larry Paul Fidler allowed the proceedings in Los Angeles Superior Court to be televised.[107] On September 26, Fidler declared a mistrial because of a hung jury (ten to two for conviction).[110][111]

Released in December 2007, the song "B Boy Baby" by Mutya Buena and Amy Winehouse featured melodic and lyrical passages heavily influenced by "Be My Baby". As a result, Spector was given a songwriting credit on the single. The sections from "Be My Baby" were sung by Winehouse, not sampled from the mono single.[112] Winehouse referenced her admiration of Spector's work and often performed Spector's first hit song, "To Know Him Is to Love Him".[113] That same month, Spector attended the funeral of Ike Turner. In his eulogy, Spector criticized Tina Turner's autobiography—and its subsequent promotion by Oprah Winfrey—as a "badly written" book that "demonized and vilified Ike". Spector commented that "Ike made Tina the jewel she was. When I went to see Ike play at the Cinegrill in the '90s ... there were at least five Tina Turners on the stage performing that night, and any one of them could have been the real Tina Turner."[114]

In mid-April 2008, BBC Two broadcast a special titled Phil Spector: The Agony and the Ecstasy, by Vikram Jayanti. It consists of Spector's first screen interview—breaking a long period of media silence. During the conversation, images from the murder court case are juxtaposed with live appearances of his tracks on television programs from the 1960s and 1970s, along with subtitles giving critical interpretations of some of his song production values. While he does not directly try to clear his name, the court case proceedings shown try to give further explanation of the facts surrounding the murder charges leveled against him. He also speaks about the musical instincts that led him to create some of his most enduring hit records, from "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" to "River Deep, Mountain High", as well as Let It Be, along with criticisms he feels he has had to deal with throughout his life.[115]

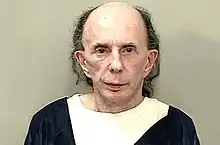

.jpg.webp)

The retrial of Spector for murder in the second degree began on October 20, 2008,[116] with Judge Fidler again presiding; the retrial was not televised. Spector was once again represented by attorney Jennifer Lee Barringer.[117] The case went to the jury on March 26, 2009, and 18 days later, on April 13, the jury returned a guilty verdict.[118][119] Additionally, Spector was found guilty of using a firearm in the commission of a crime, which added four years to the sentence.[120] He was immediately taken into custody and, on May 29, 2009, was sentenced to 19 years to life in the California state prison system.[121][122][123][124] Various attempted appeals were unsuccessful, in 2011, 2012, and 2016.[125][126][127]

Musicianship

Spector's early musical influences included Latin music in general, and Latin percussion in particular.[128] This is perceptible in many if not all of Spector's recordings, from the percussion in many of his hit songs: shakers, güiros (gourds), and maracas in "Be My Baby" and the son montuno in "You've Lost That Lovin' Feeling" (heard clearly in the song's bridge, played by session bassist Carol Kaye, while the same repeating refrain is played on harpsichord by Larry Knechtel).

Spector's trademark during his recording career was the so-called Wall of Sound, a production technique yielding a dense, layered effect that reproduced well on AM radio and jukeboxes. To attain this signature sound, Spector gathered large groups of musicians (playing some instruments not generally used for ensemble playing, such as electric and acoustic guitars) playing orchestrated parts—often doubling and tripling many instruments playing in unison—for a fuller sound. Spector himself called his technique "a Wagnerian approach to rock & roll: little symphonies for the kids".[129]

Spector directed the overall sound of his recordings, using a core group that became known as the Wrecking Crew, including session players such as Hal Blaine, Larry Knechtel, Steve Douglas, Carol Kaye, Roy Caton, Glen Campbell, and Leon Russell. He delegated arrangements to Jack Nitzsche and had Sonny Bono oversee the performances, viewing these two as his "lieutenants".[130] Spector frequently used songs from songwriters employed at the Brill Building (Trio Music) and at 1650 Broadway (Aldon Music), such as the teams of Ellie Greenwich and Jeff Barry, Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, and Gerry Goffin and Carole King. He often worked with the songwriters, receiving co-credit and publishing royalties for compositions.[131]

Despite the trend towards multichannel recording, Spector was vehemently opposed to stereo releases, saying that it took control of the record's sound away from the producer in favor of the listener.[132] Sometimes a pair of strings or horns would be double-tracked multiple times to sound like an entire string or horn section. But in the final product the background sometimes could not be distinguished as either horns or strings. Spector also greatly preferred singles to albums, describing LPs as "two hits and ten pieces of junk", reflecting both his commercial methods and those of many other producers at the time.[133]

Legacy and influence

According to guitarist Stevie Van Zandt of the E Street Band, Spector was a "genius irredeemably conflicted". On Twitter, he wrote: "[Spector] was the ultimate example of the art always being better than the artist... [He] made some of the greatest records in history based on the salvation of love while remaining incapable of giving or receiving love his whole life."[134]

Spector is often called the first auteur among musical artists[9][135] for acting not only as a producer, but also the creative director, writing or choosing the material, supervising the arrangements, conducting the vocalists and session musicians, and masterminding all phases of the recording process.[8] He helped pave the way for art rock,[11] and helped inspire the emergence of aesthetically oriented genres such as shoegaze[9] and noise music.[136] PopMatters editor John Bergstrom credits the start of dream pop to Spector's collaboration with George Harrison on All Things Must Pass.[137]

His influence has been claimed by performers such as the Beatles, the Beach Boys,[138] and the Velvet Underground[139] alongside latter-day record producers such as Brian Eno and Tony Visconti.[140][141] Alternative rock performers Cocteau Twins,[142] My Bloody Valentine,[138] and the Jesus and Mary Chain[138] have all cited Spector as an influence. Shoegaze, a British musical movement in the late 1980s to mid-1990s, was heavily influenced by the Wall of Sound. Jason Pierce of Spiritualized has cited Spector as a major influence on his Let It Come Down album. Bobby Gillespie of Primal Scream and the Jesus and Mary Chain has enthused about Spector, with the song "Just Like Honey" opening with an homage of the famous "Be My Baby" drum intro.[143]

Many have tried to emulate Spector's methods, and Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys—a fellow adherent of mono recording—considered Spector his main competition as a studio artist. In the 1960s, Wilson thought of Spector as "the single most influential producer. He's timeless. He makes a milestone whenever he goes into the studio."[144] Wilson's fascination with Spector's work has persisted for decades, with many different references to Spector and his work scattered around Wilson's songs with the Beach Boys and even his solo career. Of Spector-related productions, Wilson has been involved with covers of "Be My Baby", "Chapel of Love", "Just Once in My Life", "There's No Other (Like My Baby)", "Then He Kissed Me", "Talk to Me", "Why Don't They Let Us Fall in Love", "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'", "Da Doo Ron Ron", "I Can Hear Music", and "This Could Be the Night".[145]

Johnny Franz's mid-1960s productions for Dusty Springfield and the Walker Brothers also employed a layered, symphonic "Wall of Sound" arrangement-and-recording style, heavily influenced by the Spector sound.[146] Another example is the Forum, a studio project of Les Baxter, which produced a minor hit in 1967 with "The River Is Wide". Sonny Bono, a former associate of Spector's, developed a jangly, guitar-laden variation on the Spector sound, which is heard mainly in mid-1960s productions for his then-wife Cher, notably "Bang Bang (My Baby Shot Me Down)".

Bruce Springsteen emulated the Wall of Sound technique in his recording of "Born to Run".[11] In 1973, the British band Wizzard, led by Roy Wood, had three Spector-influenced hits with "See My Baby Jive", "Angel Fingers (A Teen Ballad)", and "I Wish It Could Be Christmas Everyday", the latter becoming a perennial Christmas hit.[11] Other contemporaries influenced by Spector include George Morton, Sonny & Cher, the Rolling Stones, the Four Tops, Mark Wirtz, the Lovin' Spoonful, and the Beatles.[147] Swedish pop group ABBA cited Spector as an influence, and used similar Wall of Sound techniques in their early songs, including "Ring Ring", "Waterloo", and "Dancing Queen".[148] The Los Angeles-based new wave band Wall of Voodoo takes their name from Spector's Wall of Sound.[149] Spector's influence is also felt in other areas of the world, especially Japan. City pop musician Eiichi Ohtaki has been influenced by Spector and the Wall of Sound.[150][151]

Personal life

Relationships and children

Spector's first marriage was in 1963 to Annette Merar, lead vocalist of the Spectors Three, a 1960s pop trio formed and produced by Spector. He named a record company after Merar, Annette Records.[152] Spector and Merar divorced in 1966.[153] While still married to Merar, he began having an affair with Ronnie Bennett, later known as Ronnie Spector.[154] Bennett was the lead singer of the girl group the Ronettes (another group Spector managed and produced). They married in 1968 and adopted a son, Donté Phillip Spector.[155] As a Christmas present, Spector surprised her by adopting twins Louis Phillip Spector and Gary Phillip Spector.[155][156]

In her 1990 memoir, Be My Baby: How I Survived Mascara, Miniskirts And Madness, Bennett alleged that Spector had imprisoned her in his California mansion and subjected her to years of psychological torment. According to Bennett, Spector sabotaged her career by forbidding her to perform. She escaped from the mansion barefoot with the help of her mother in 1972.[156][157] In their 1974 divorce settlement, she forfeited all future record earnings and surrendered custody of their children. She alleged that this was because Spector threatened to hire a hitman to kill her.[158]

Spector's sons Gary and Donté both stated that their father "kept them captive" as children, and that they were "forced to perform simulated intercourse" with his girlfriend. According to Gary, "I was blindfolded and sexually molested. Dad would say, 'You're going to meet someone,' and it would be a 'learning experience'."[159][160] Donté described himself as coming "from a very sick, twisted, dysfunctional family".[159]

In 1982, Spector had twin children with his girlfriend Janis Zavala: Nicole Audrey Spector and Phillip Spector Jr. Phillip Jr. died of leukemia in 1991.[155][161] On September 1, 2006, while on bail and awaiting trial, Spector married his third wife Rachelle Short, who was 26 at the time. Spector filed for divorce in April 2016, claiming irreconcilable differences.[162] They divorced in 2018.[163]

Health, illness, and death

Spector testified in a 2005 court deposition that he had been treated for bipolar disorder ("manic depression") for eight years, saying, "No sleep, depression, mood changes, mood swings, hard to live with, hard to concentrate, just hard—a hard time getting through life, I've been called a genius and I think a genius is not there all the time and has borderline insanity."[164]

In the first criminal trial for the Clarkson murder, defense expert and forensic pathologist Vincent Di Maio said that Spector might be suffering from Parkinson's disease stating, "Look at Mr. Spector. He has Parkinson's features. He trembles."[165]

California Department of Corrections photos from 2013 (released in September 2014) show evidence of a progressive deterioration in Spector's health, according to observers.[166][167] He had been an inmate at the California Health Care Facility (a prison hospital) in Stockton since October 2013.[168] In September 2014, it was reported that Spector had lost his ability to speak, owing to laryngeal papillomatosis.[168][169]

He was taken to San Joaquin General Hospital in French Camp, California, on December 31, 2020, and intubated in January 2021.[170] Spector died in an outside hospital on January 16 at the age of 81, according to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.[171][172][173][174] Spector's daughter Nicole attributed her father's death to complications of COVID-19, with which he was diagnosed in December 2020.[170] He would have been eligible for parole in 2024.[122]

Some media outlets that reported on Spector's death were subject to controversy for reportedly downplaying his murder conviction. Examples given were the obituaries in The New York Times and Rolling Stone, which originally stated, respectively, that Spector's legacy "was marred by a murder conviction" and that his "life was upended" after being sentenced. These obituaries were revised following a social media backlash.[2]

In popular culture

- I Dream of Jeannie (1967, "Jeannie, the Hip Hippie" – season 3, episode 6): Phil Spector made a cameo as himself. Jeannie decides she wants to be a pop star and enlists Spector for help. Though referred to by the characters throughout the episode as "Phil Spector", the credit roll lists "Phil Spector as 'Steve Davis'".[175]

- Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970): The character of Ronnie "Z-Man" Barzell is based upon Spector, though neither Russ Meyer nor screenwriter Roger Ebert had met him.[176]

- Phantom of the Paradise (1974): The villainous character Swan (played by Paul Williams) was supposedly inspired by Spector. A music producer and head of a record label, Swan was named "Spectre" in original drafts of the film's screenplay.[177]

- What's Love Got to Do with It (1993): Spector is portrayed by Rob LaBelle.[178]

- Grace of My Heart (1996): The film contains many characters based upon 1960s musicians, writers and producers including the character Joel Milner played by John Turturro (based on Spector).[179]

- In the docudrama And the Beat Goes On: The Sonny and Cher Story, Phil Spector is portrayed by Christian Leffler.

- Metalocalypse (2006–2013): The character Dick Knubbler is a parody of Spector, based on profession, appearance and record of assault.[180]

- A Reasonable Man (2009): Harv Stevens is reportedly based on Spector. The film examines his relationship with John Lennon.[181]

- Phil Spector (2013): Spector is portrayed by Al Pacino.[182]

- Love & Mercy (2014): Spector is portrayed by Jonathan Slavin. However, his scene was cut from the theatrical release.[183]

- He was also in Easy Rider as a drug dealer.

- The song "Christmas Kids" by ROAR references Spector's relationship with Ronnie Spector, the two also appear on the cover of the EP.

Discography

Awards

Spector is one of a handful of producers to have number one records in three consecutive decades (1950s, 1960s and 1970s). Others in this group include Quincy Jones (1960s, 1970s, and 1980s), George Martin (1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s), Michael Omartian (1970s, 1980s and 1990s), Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis (1980s, 1990s, and 2000s), and Max Martin (1990s, 2000, 2010s, and 2020s).[184][185]

Awards and nominations

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1972 | George Harrison "My Sweet Lord" | Grammy Award for Record of the Year[101] | Nominated |

| 1972 | George Harrison All Things Must Pass | Grammy Award for Album of the Year[101] | Nominated |

| 1973 | George Harrison & Friends The Concert for Bangladesh | Grammy Award for Album of the Year[186] | Won |

| 1989 | Phil Spector | Rock and Roll Hall of Fame[99] | Inducted |

| 1997 | Phil Spector | Songwriter's Hall of Fame[13] | Inducted |

| 2000 | Phil Spector | Grammy Trustees Award[101] | Won |

Rankings

| Publication | Country | Accolade | Year | Rank | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rolling Stone | US | Greatest Artists of All Time | 2004, updated 2011 | 64 | [187] |

| The Washington Times | US | Greatest Record Producers of All Time | 2008 | 2 | [188] |

Notes

- Some sources erroneously cite 1940 as his year of birth.[18]

- Spector also co-produced, with Lennon and Yoko Ono, the Elastic Oz Band's "God Save Us",[73] a single protesting the jailing of Oz magazine's editors on obscenity charges.[74]

- In the same 1987 interview, Harrison said Spector's problems with alcohol and his frequent hospitalisation typified their collaborations from 1970 onward. He nevertheless described the producer as "brilliant ... one of the greatest", adding, "he should be out there doing stuff right now—but not with me!"[82]

- When asked about reports that Spector had fired his gun into the ceiling, Lennon said: "I don't like to tell tales out of school ... But I do know there was an awful loud noise in the toilet of the Record Plant West."[87]

- The band still name-checked Spector in the song "It's Not My Place (in the 9 to 5 World)" on their next album, Pleasant Dreams.

References

- Grimes, William (January 17, 2021). "Phil Spector, Famed Music Producer and Convicted Murderer, Dies at 81". The New York Times.

- Wood, Mikael (January 18, 2021). "Phil Spector and the damaging myth of male creative genius". Los Angeles Times.

- Spillius, Alex. "Phil Spector guilty of murdering actress Lana Clarkson". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on February 11, 2018. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- Brown 2007, p. 1.

- Brown, Mick (February 4, 2003). "Pop's lost genius". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on September 10, 2018. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- Williams 2003, p. 5.

- Wolfe, Tom (January 3, 1965). "First Tycoon of Teen". New York Magazine, published as a supplement to the New York Herald Tribune. (This appears in the microfilm edition of the Herald Tribune but apparently not in the online database)

- Williams 2003, p. 23.

- Bannister 2007, p. 38.

- Holden, Stephen (February 28, 1999). "Music; They're Recording, but Are They Artists?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 30, 2016. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- Williams 2003, p. 25.

- Wiseman-Trowse, Nathan (September 30, 2008). Performing Class in British Popular Music. Springer. pp. 148–154. ISBN 9780230594975.

- "Phil Spector". Songwriters Hall of Fame. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- See:

- "100 Greatest Artists of All Time". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 19, 2011. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- "The Immortals: Phil Spector". Rolling Stone. No. 946. Archived from the original on May 18, 2009. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- Sevigny, Catherine (May 5, 2007). "Wall of silence". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 24, 2019. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- Unterberger, Richie. "Phil Spector". AllMusic. Archived from the original on May 2, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- Thompson 2004, p. 10.

- Brown 2007, p. 14.

- Brown 2007, pp. 14, 19.

- "Benjamin Spector". January 10, 1903.

- "Bertha Spector". July 15, 1911.

- Brown 2007, pp. 12–14.

- Williams 2003, p. 27.

- Brown 2007, p. 13.

- Brown 2007, p. 12.

- Thompson 2004, p. 12.

- Brown 2007, p. 17.

- Thompson 2004, p. 13.

- Brown 2007, p. 19.

- Thompson 2005, p. 28.

- Larkin, Colin (2002). The Virgin Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Virgin Publishing. ISBN 1-85227-923-0.

- Brown 2007, p. 37.

- Thompson 2004, p. 26.

- Fred Bronson, The Billboard Book of Number One Hits, Billboard Publications, 1992, p. 46

- Brown 2007, pp. 44, 48.

- Brown 2007, p. 55.

- Thompson 2005, pp. 58, 98.

- Ribowsky 2006, pp. 86–88.

- Whitburn, Joel (2004). The Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits: Eighth Edition. Record Research. p. 480.

- Brown 2007, p. 86.

- Joel Whitburn's Top Pop Singles 1955–1990 - ISBN 0-89820-089-X

- Thompson 2005, p. 79.

- "Spector Named To A&R Post At Liberty" (PDF). Cash Box. March 17, 1962. p. 27. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 18, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- Spector, Ronnie (1990). Be My Baby, How I Survived Mascara, Miniskirts, and Madness or My Life as a Fabulous Ronette. Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0517574997. Archived from the original on December 18, 2020. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- "1966". billboard Top 100. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- Brown 2007, p. 184.

- Dimery, Robert (2011). 1001 Songs: You Must Hear Before You Die. Cassell Illustrated. ISBN 978-1844037179. Archived from the original on January 25, 2016. Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- Ramone, Marky (2017). Punk Rock Blitzkrieg – My Life As A Ramone. Kings Road Publishing. p. 177. ISBN 978-1786068170. Archived from the original on December 18, 2020. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- "Philips Signs Ike & Tina Turner" (PDF). Cash Box. April 23, 1966. p. 45. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 18, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Ike & Tina to Philles" (PDF). Cash Box. April 30, 1966. p. 56. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 18, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 21 – Forty Miles of Bad Road: Some of the best from rock 'n' roll's dark ages. Part 2]: UNT Digital Library" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries.

- "Negotiations Continue For Spector Deal With A&M" (PDF). Cash Box. May 27, 1967. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 18, 2020. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- "Spector, A&M Deal" (PDF). Cash Box. June 3, 1967. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 18, 2020. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- Williams 2003, pp. 128–137.

- Dave Thompson (2010). Phil Spector: Wall Of Pain. Omnibus Press. pp. 268–. ISBN 978-0-85712-216-2.

- Schaffner 1978, p. 137.

- Ribowsky 2006, p. 252.

- Hamelman 2009, pp. 136–37.

- Kreps, Daniel. "'Let It Be' 40 Years Later: A Look Back at the Beatles' Final LP". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 5, 2017. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- Brown 2007, pp. 254–55.

- Wenner, Jann S. (January 21, 1971). "Lennon Remembers, Part One". Rolling Stone. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- Cavanagh, David (August 2008). "George Harrison: The Dark Horse". Uncut. p. 41.

- Madinger & Easter 2000, p. 427.

- Schaffner 1978, p. 142.

- Frontani 2009, pp. 157–58.

- Ribowsky 2006, p. 256.

- Ribowsky 2006, p. 257.

- Frontani 2009, pp. 158–59.

- Spizer 2005, p. 342.

- Madinger & Easter 2000, pp. 427, 434.

- Williams 2003, p. 162.

- Schaffner 1978, p. 160.

- Madinger & Easter 2000, pp. 44–45.

- Spizer 2005, p. 49.

- Williams 2003, p. 163.

- Badman, Keith (2009). The Beatles Diary Volume 2: After The Break-Up 1970–2001. Omnibus Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0857120014. Archived from the original on December 18, 2020. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- "Concert For Bangladesh". albumlinernotes.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- Kubernik, Harvey (November 10, 2020). "George Harrison 'All Things Must Pass' 50th Anniversary". Music Connection. Retrieved January 18, 2021..

- Williams 2003, p. 166.

- Spizer 2005, p. 62.

- Spizer 2005, p. 254.

- White, Timothy (November 1987). "George Harrison – Reconsidered". Musician. p. 53.

- Schaffner 1978, pp. 175, 195.

- Schaffner 1978, p. 175.

- Doggett 2011, pp. 210–11.

- Madinger & Easter 2000, p. 90.

- Spizer 2005, p. 98.

- Madinger & Easter 2000, p. 91.

- Harris, Keith (January 17, 2021). "Phil Spector". Rolling Stone.

- Leibovitz, Liel (December 11, 2012). "Wall of Crazy: Phil Spector and Leonard Cohen's incredible album, released 35 years ago, is a time capsule of American pop music". Tablet: A New Read on Jewish Life. Nextbook Inc. Archived from the original on December 15, 2014. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- "Phil Spector's Terrifying MugShot Is Horrible". SquareMirror.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- Cox, Tom (February 10, 2001). "A masterpiece? Was it?". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on April 5, 2018. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- Roberts, Randall (April 10, 2009). "Leonard Cohen's Prophecy of the Phil Spector/Lana Clarkson Incident: 'Death of a Ladies' Man'". L.A. Weekly. Archived from the original on July 16, 2015. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- Devenish, Colin (June 24, 2002). "Johnny Ramone Stays Tough: Ramones Guitarist Reflects on Dee Dee's Death and the Difficult Eighties". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 1, 2009. Retrieved January 5, 2008.

- "The Curse of the Ramones". Rolling Stone. May 19, 2016. Archived from the original on April 19, 2018. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- "Marky Ramone: 'Phil Spector didn't hold a gun to us'". NME. December 2, 2008. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2009.

- Minsky, David (April 7, 2015). "Marky Ramone on Phil Spector: "He Never Pointed a Gun at Us" – Miami New Times". Miami New Times. Archived from the original on July 17, 2015. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- Brock Helander (January 1, 2001). The Rockin' 60s: The People Who Made the Music. Schirmer Trade Books. pp. 659–. ISBN 978-0-85712-811-9.

- Rogers, Sheila (March 9, 1989). "The 1989 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony". Rolling Stone. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- Fricke, David; Rogers, Sheila (March 9, 1989). "The 1989 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony". Rolling Stone.

- "Phil Spector". Recording Academy Grammy Awards. November 23, 2020.

- "Phil Spector blasts The Ronettes' Hall Of Fame induction". NME. March 7, 2007.

- Willaman, Chris (December 3, 2004). "Here's Celine Dion's 1995 buried treasure". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- "Music – Review of Starsailor – Silence Is Easy". BBC. Archived from the original on November 26, 2017. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- Bruno, Anthony. "Phil Spector: The 'mad genius' of rock'n'roll". TruTV.com. Archived from the original on December 10, 2012.

- "Phil Spector and the wall of charges". The Guardian. London, UK. March 16, 2007. Archived from the original on December 19, 2018. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- "US Spector trial to be televised". BBC News. London: BBC. February 17, 2007. Archived from the original on March 8, 2008. Retrieved March 9, 2007.

- "In Your Eyes – Hargo". Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards. AllMusic. July 24, 2006. Archived from the original on May 2, 2020. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- "Phil Spector continues work in studio". NME. August 13, 2007. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- Archibold, Randal C. (September 27, 2007). "Mistrial Declared in Spector Murder Case". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 16, 2009. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- Morrison, Keith (September 12, 2007). "Facing the music". New York City: NBC News. Archived from the original on December 19, 2018. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- "Mutya Buena". NME. June 1, 2007. Archived from the original on April 15, 2016. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- "Amy Winehouse: To know him is to love him (live)". October 31, 2009. Archived from the original on June 6, 2016. Retrieved June 30, 2010 – via YouTube.

- "Phil Spector criticises Tina Turner at Ike Turner's funeral". NME. December 23, 2007. Archived from the original on September 7, 2016. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- Thorpe, Vanessa (February 18, 2008). "Phil Spector breaks his silence before second trial for murder". The Guardian. Music Guardian. London. Archived from the original on December 18, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- "Phil Spector murder retrial gets underway, Jury selection begins in LA". NME. London: TI Media. October 21, 2008. Archived from the original on June 16, 2013. Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- "Attorney Jennifer Barringer (L) looks on pictures". Getty Images. Archived from the original on February 2, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- Li, David K. (April 13, 2009). "Phil Spector faces the music". New York Post. Archived from the original on July 27, 2009. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- "Phil Spector convicted of murder". BBC News. London: BBC. April 13, 2009. Archived from the original on April 14, 2009. Retrieved April 13, 2009.

- "Phil Spector found guilty of 2nd degree murder". Associated Press. April 13, 2009. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- Duke, Alan (May 29, 2009). "Phil Spector gets 19 years to life for murder of actress". CNN. Archived from the original on September 23, 2010. Retrieved May 30, 2009.

- "CDCR Inmate Locator". cdcr.ca.gov. Archived from the original on December 18, 2020. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- Weber, Christopher; Deutsch, Linda (January 17, 2021). "Phil Spector, famed music producer and murderer, dies at 81". Associated Press – via Yahoo!.

- Davies, Caroline (January 17, 2021). "Phil Spector, pop producer convicted of murder, dies aged 81". The Guardian.

- "Phil Spector denied murder appeal". BBC. August 18, 2011. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- Sean Michaels (February 22, 2012). "Phil Spector appeal rejected by US supreme court". The Guardian. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

The music producer's conviction for the murder of Lana Clarkson in 2003 will not be overturned after court refuses to hear appeal ... The court let stand a California appeals court ruling last May that upheld Spector's conviction for the murder of Lana Clarkson in 2003. The court offered no comment on the case.

- "Phil Spector's Battle For Freedom Is Over! Judge Rules On Appeal". Radar Online. June 17, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- Palmer, Robert (March 20, 1977). "Phil Spector‐Master Of the 60's Sound". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 19, 2018. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- DeCurtis, Anthony (1999). Rocking My Life Away: Writing about Music and Other Matters. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. p. 142. ISBN 0822324199. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- Eddy, Chuck (April 2011). "Essentials: A Mad Genius Turns the Wall of Sound Into Rock's Most Transcendent Trick". Spin. p. 79. Archived from the original on December 18, 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2018 – via Google Books.

- Ryan, Harriet (April 8, 2009). "Spector's long legal battles may be sapping his fortune". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 17, 2016. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- "Entertainment | Phil Spector's Wall of Sound". BBC News. London, England: BBC. April 14, 2009. Archived from the original on March 26, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- Brown 2007, pp. 184–185.

- Landrum, Jonathon Jr. (January 17, 2021). "Phil Spector's death resurrects mixed reaction from skeptics". Los Angeles. Associated Press.

But while Spector made his mark as a revolutionary music producer, the stories of him waving guns at recording artists and being convicted of murder overshadowed his artistry.

- Eisenberg 2005, p. 103.

- Bannister 2007, p. 158.

- Bergstrom, John (January 13, 2011). "George Harrison: All Things Must Pass". PopMatters. Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved April 28, 2014.

- Bannister 2007, p. 39.

- Reed, Lou (December 1966). "The View from the Bandstand". Aspen Magazine. No. 3.

- Tamm, Eric (1995). Brian Eno: His Music and the Vertical Color of Sound (Updated ed., 1. Da Capo Press ed.). New York: Da Capo Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-306-80649-0. Archived from the original on May 17, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- "Lecture: Tony Visconti (Madrid 2011)". Red Bull Music Academy. 2012. Archived from the original on January 23, 2015. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- Guthrie, Robin (November 6, 1993). "Robin Guthrie of Cocteau Twins Talks about the Records That Changed His Life". Melody Maker. p. 27.

- Adams, Erik; Casciato, Cory; Eakin, Marah; Heller, Jason; Sava, Oliver; Zaleski, Annie (September 2, 2013). "Kick kick kick snare, repeat: 15 songs that borrow the drum intro from 'Be My Baby'". AV Club. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- Grevatt, Ron (March 19, 1966). "Beach Boys' Blast". Melody Maker. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved June 23, 2013.

- Lambert, Philip (2007). Inside the Music of Brian Wilson: the Songs, Sounds, and Influences of the Beach Boys' Founding Genius. Continuum. pp. 331–79. ISBN 978-0-8264-1876-0. Archived from the original on May 15, 2016. Retrieved April 8, 2016.

- Ward, Kit (2018). City of Song: A London Sixties Music Trail. Prydain Press. pp. 35–. ISBN 978-1-916469-31-0.

- Williams 2003, p. 24.

- Really Easy Piano: ABBA. Wise Publications. 2012. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-0-85712-947-5.

- Jennings, Steve (March 1, 2005). "Classic Tracks: Wall of Voodoo's "Mexican Radio"". Mix. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- B., Sheila (August 13, 2013). "Nippon Girls: Japanese Synth-pop, Bubble-gum, and Ballads Mix (1971-1985)". Chacha Charming. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- "Eiichi Ohtaki- Japanese music otaku legend". jculinferno. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- "Phil Spector's first wife reported missing". Daily Breeze. July 20, 2009. Archived from the original on December 18, 2020. Retrieved September 13, 2019.

- Williams, Richard (January 12, 2022). Phil Spector: Out Of His Head. ISBN 9780857120564. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- "Spector, Ronnie Study Guide & Homework Help". eNotes.com. Archived from the original on December 18, 2020. Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- "Phil Spector, Pop Music Hitmaker Convicted of Murder, Dies at 81". Bloomberg. January 17, 2021. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- Muller, Marissa G. (November 12, 2013). "Ronnie Spector: The Original Icon". Vice. Archived from the original on May 2, 2020. Retrieved September 13, 2019.

- Hoby, Hermione (March 6, 2014). "Ronnie Spector interview: 'The more Phil tried to destroy me, the stronger I got'". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on May 29, 2014. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- Arena, Salvatore (June 11, 1998). "Marriage Hit Wrong Chord, Says Ronette". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on July 2, 2019. Retrieved September 13, 2019.

- "Spector's Sons: Dad Caged Us". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- Willis, Tim (April 18, 2007). "Phil Spector's troubled life". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on September 13, 2018. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

- Sam, Robert. "Legend with a Bullet". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on November 30, 2009. Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- "Phil Spector Files for Divorce: My Wife's Killing Me". TMZ. April 23, 2016. Archived from the original on May 2, 2020. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- "Phil Spector Fast Facts". CNN. March 25, 2021.

- Weber, Christopher; Deutsch, Linda (January 17, 2021). "Phil Spector, famed music producer and murderer, dies at 81". AP News.

- "Defense expert, prosecutor spar in Phil Spector murder trial". USA Today. June 28, 2007. Archived from the original on August 18, 2007. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- Phil Spector: New photos show toll of age, prison on pop legend Archived September 27, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Published September 23, 2014. Retrieved September 24, 2014.

- Phil Spector photos show prison taking its toll Archived September 24, 2014, at the Wayback Machine The Times. Retrieved September 24, 2014.

- "Jailed Phil Spector's wall of silence as he loses ability to speak". Daily Mirror. September 26, 2014. Archived from the original on December 21, 2017. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

- "Music producer Phil Spector loses voice, now in facility for sick inmates". Daily News. New York. September 27, 2014. Archived from the original on September 30, 2014. Retrieved October 2, 2014.

- Grimes, William (January 17, 2021). "Phil Spector, Famed Music Producer Imprisoned in Slaying, Dies at 81". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- "CDCR Inmate Locator". California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. Archived from the original on December 18, 2020. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- Cromelin, Richard; Wigglesworth, Alex; Winton, Richard (January 17, 2021). "Phil Spector, music producer convicted of murder, dies at 81 after contracting COVID-19". Obituaries. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

Before he was transferred to a hospital, Spector had been an inmate at the California Health Care Facility in Stockton

- Whitcomb, Dan (January 18, 2021). "Phil Spector, music producer and convicted killer, dies after contracting COVID-19". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- Davies, Caroline (January 17, 2021). "Phil Spector, pop producer convicted of murder, dies aged 81". The Guardian. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- "Phil Spector on 'I Dream of Jeannie' (with Boyce & Hart)". DangerousMinds. April 1, 2013. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- Ebert, Roger (January 1, 1970). "Beyond the Valley of the Dolls". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on December 30, 2018. Retrieved February 13, 2020 – via rogerebert.com.

- "Production". The Swan Archives. October 4, 1974. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- Schäfer, Horst (1994). Fischer Film Almanach. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag. p. 339.

- Kermode, Mark (March 23, 2006). "John Turturro". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 17, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- Daly, Joe (March 28, 2020). "The 10 best moments from Metalocalypse". Metal Hammer Magazine. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- "Article at Exclaim.com". Exclaim!. Archived from the original on July 29, 2012. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- Phil Spector (2013). Rotten Tomatoes, retrieved January 17, 2021

- MacLeod, Sean (November 15, 2017). Phil Spector: Sound of the Sixties. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-4422-6706-0.

- Bronson, Fred (2003). Billboard's Hottest Hot 100 Hits. Billboard Books (3rd ed.), pp. 106–28.

- Whitburn, Joel (2013). Joel Whitburn's Top Pop Singles 1955–2012. Record Research (14th ed.).

- "GRAMMY Rewind: 15th Annual GRAMMY Awards". National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. December 2, 2014. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- "100 Greatest Artists (80-61)". Rolling Stone. December 3, 2010. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- "Top 5: Knob-twiddlers". The Washington Times. July 4, 2008. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

Bibliography

- Bannister, Matthew (2007). White Boys, White Noise: Masculinities and 1980s Indie Guitar Rock. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-8803-7.

- Brown, Mick (2007). Tearing Down the Wall of Sound: The Rise and Fall of Phil Spector. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781400042197.

- Doggett, Peter (2011). You Never Give Me Your Money: The Beatles After the Breakup. New York, NY: It Books. ISBN 978-0-06-177418-8.

- Eisenberg, Evan (2005). The Recording Angel: Music, Records and Culture from Aristotle to Zappa. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09904-1.

- Frontani, Michael (2009). "The Solo Years". In Womack, Kenneth (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Beatles. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68976-2.

- Hamelman, Steve (2009). "On Their Way Home: The Beatles in 1969 and 1970". In Womack, Kenneth (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Beatles. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68976-2.

- Madinger, Chip; Easter, Mark (2000). Eight Arms to Hold You: The Solo Beatles Compendium. Chesterfield, MO: 44.1 Productions. ISBN 0-615-11724-4.

- Ribowsky, Mark (2006). He's a Rebel: Phil Spector – Rock and Roll's Legendary Producer. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81471-6.

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1978). The Beatles Forever. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-055087-5.

- Spizer, Bruce (2005). The Beatles Solo on Apple Records. New Orleans, LA: 498 Productions. ISBN 0-9662649-5-9.

- Sumrall, Harry (1994). Pioneers of Rock and Roll: 100 Artists Who Changed the Face of Rock. New York: Billboard Books. ISBN 0823076288.

- Thompson, Dave (2004). Wall of Pain: The Biography of Phil Spector (Paperback ed.). London: Sanctuary. ISBN 978-1-86074-543-0.

- Thompson, Dave (2005). Wall of Pain: The Life of Phil Spector (New ed.). London: Sanctuary. ISBN 9781860746451.

- Williams, Richard (2003). Phil Spector: Out of His Head (Paperback ed.). London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-71199-864-3.

Further reading

- Baker, James Robert. Fuel-Injected Dreams New York: E. P. Dutton ISBN 0-452-25815-4; novel whose central character is reportedly based on Spector

- Emerson, Ken. Always Magic in the Air: The Bomp and Brilliance of the Brill Building Era New York: Viking Press ISBN 0-670-03456-8

- Wolfe, Tom. "The First Tycoon of Teen" — magazine article reprinted in Wolfe, The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby, ISBN 0-553-38058-3; and in Back to Mono liner notes

External links

- Phil Spector at AllMusic

- Phil Spector discography at Discogs

- Phil Spector at IMDb

- Please Phil Spector, artists that have included references to Spector in their own works