Phonetic complement

A phonetic complement is a phonetic symbol used to disambiguate word characters (logograms) that have multiple readings, in mixed logographic-phonetic scripts such as Egyptian hieroglyphs, Akkadian cuneiform, Japanese, and Mayan. Often they reenforce the communication of the ideogram by repeating the first or last syllable in the term.

Written English has few logograms, primarily numerals, and therefore few phonetic complements. An example is the nd of 2nd 'second', which avoids ambiguity with 2 standing for the word 'two'. In addition to numerals, other examples include Xmas, Xianity, and Xing for Christmas, Christianity, and Crossing – note the separate readings Christ and Cross.

In cuneiform

In Sumerian, the single word kur (𒆳) had two main meanings: 'hill' and 'country'. Akkadian, however, had separate words for these two meanings: šadú 'hill' and mātu 'country'. When Sumerian cuneiform was adapted (known as orthographic borrowing) for writing Akkadian, this was ambiguous because both words were written with the same character (𒆳, conventionally transcribed KUR, after its Sumerian pronunciation). To alert the reader as to which Akkadian word was intended, the phonetic complement -ú was written after KUR if 'hill' was intended, so that the characters KUR-ú were pronounced šadú, whereas KUR without a phonetic complement was understood to mean mātu 'country'.

Phonetic complements also indicated the Akkadian nominative and genitive cases. Similarly, Hittite cuneiform occasionally uses phonetic complements to attach Hittite case endings to Sumerograms and Akkadograms.

Phonetic complements should not be confused with determinatives (which were also used to disambiguate) since determinatives were used specifically to indicate the category of the word they preceded or followed. For example, the sign DINGIR (𒀭) often precedes names of gods, as LUGAL (𒈗) does for kings. It is believed that determinatives were not pronounced.

In Japanese

As in Akkadian, Japanese borrowed a logographic script, Chinese, designed for a very different language. The Chinese phonetic components built into these kanji (Japanese: 漢字) do not work when they are pronounced in Japanese, and there is not a one-to-one relationship between them and the Japanese words they represent.

For example, the kanji 生, pronounced shō or sei in borrowed Chinese vocabulary, stands for several native Japanese words as well. When these words have inflectional endings (verbs/adjectives and adverbs), the end of the stem is written phonetically:

- 生 nama 'raw' or ki 'alive'

- 生う [生u] o-u 'expand'

- 生きる [生kiru] i-kiru 'live'

- 生かす [生kasu] i-kasu 'make use of'

- 生ける [生keru] i-keru 'living, arrange'

- 生む [生mu] u-mu 'produce, give birth to'

- 生まれる or 生れる [生mareru or 生reru] u-mareru or uma-reru 'be born'

- 生える [生eru] ha-eru 'grow' (intransitive)

- 生やす [生yasu] ha-yasu 'grow' (transitive)

as well as the hybrid Chinese-Japanese word

- 生じる [生jiru] shō-jiru 'occur'

Note that some of these verbs share a kanji reading (i, u, and ha), and okurigana are conventionally picked to maximize these sharings.

These phonetic characters are called okurigana. They are used even when the inflection of the stem can be determined by a following inflectional suffix, so the primary function of okurigana for many kanji is that of a phonetic complement.

Generally it is the final syllable containing the inflectional ending is written phonetically. However, in adjectival verbs ending in -shii (-しい), and in those verbs ending in -ru (-る) in which this syllable drops in derived nouns, the final two syllables are written phonetically. There are also irregularities. For example, the word umareru 'be born' is derived from umu 'to bear, to produce'. As such, it may be written 生まれる [生mareru], reflecting its derivation, or 生れる [生reru], as with other verbs ending in elidable -ru.

In Phono-Semantic Characters

In Chinese

Chinese never developed a system of purely phonetic characters. Instead, about 90% of Chinese characters are compounds of a determinative (called a 'radical'), which may not exist independently, and a phonetic complement indicates the approximate pronunciation of the morpheme. However, the phonetic element is basic, and these might be better thought of as characters used for multiple near homonyms, the identity of which is constrained by the determiner. Due to sound changes over the last several millennia, the phonetic complements are not a reliable guide to pronunciation. Also, sometimes it is not obvious at all where the phonetic complements reside, for instance, the phonetic complement in 聽 is 𡈼, in 類 is 頪, and in 勝 is 朕, etc.

In Vietnamese

Chữ Nôm of Vietnamese is almost all constructed as phono-semantic characters, whose phonetic component and semantic component are usually individual unabridged Chinese characters (like the Chữ Nôm 𣎏 and 𣩂), instead of often radicals as in Sinographs.

In the Maya Script

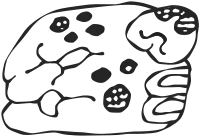

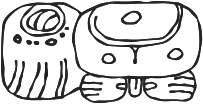

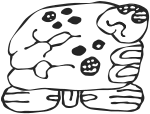

The Maya Script, the logosyllabic orthography of the Maya Civilization, used phonetic complements extensively[1] and phonetic complements could be used synharmonically or disharmonically.[2] The former is exemplified by the placement of the syllabogram for ma underneath the logogram for "jaguar" (in Classic Maya, BALAM): thus, though pronounced "BALAM", the word for "jaguar" was spelled "BALAM-m(a)". Disharmonic spellings also existed[3] in the Maya Script.[4]

See also

References

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 15, 2008. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - DISHARMONY IN MAYA HIEROGLYPHIC WRITING: LINGUISTIC CHANGE AND CONTINUITY IN CLASSIC SOCIETY

- http://www.famsi.org/research/pitts/MayaGlyphsBook1Sect1.pdf

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 20, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)