Phrase (music)

In music theory, a phrase (Greek: φράση) is a unit of musical meter that has a complete musical sense of its own,[5] built from figures, motifs, and cells, and combining to form melodies, periods and larger sections.[6]

A phrase is a substantial musical thought, which ends with a musical punctuation called a cadence. Phrases are created in music through an interaction of melody, harmony, and rhythm.[7]

Terms such as sentence and verse have been adopted into the vocabulary of music from linguistic syntax.[8] Though the analogy between the musical and the linguistic phrase is often made, still the term "is one of the most ambiguous in music....there is no consistency in applying these terms nor can there be...only with melodies of a very simple type, especially those of some dances, can the terms be used with some consistency."[9]

John D. White defines a phrase as "the smallest musical unit that conveys a more or less complete musical thought. Phrases vary in length and are terminated at a point of full or partial repose, which is called a cadence."[10] Edward Cone analyses the "typical musical phrase" as consisting of an "initial downbeat, a period of motion, and a point of arrival marked by a cadential downbeat".[11] Charles Burkhart defines a phrase as "Any group of measures (including a group of one, or possibly even a fraction of one) that has some degree of structural completeness. What counts is the sense of completeness we hear in the pitches not the notation on the page. To be complete such a group must have an ending of some kind … . Phrases are delineated by the tonal functions of pitch. They are not created by slur or by legato performance ... . A phrase is not pitches only but also has a rhythmic dimension, and further, each phrase in a work contributes to that work's large rhythmic organization."[12]

Duration or form

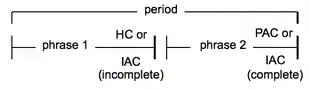

In common practice phrases are often four bars or measures long[13] culminating in a more or less definite cadence.[14] A phrase will end with a weaker or stronger cadence, depending on whether it is an antecedent phrase or a consequent phrase, the first or second half of a period.

However, the absolute span of the phrase (the term in today's use is coined by the German theorist Hugo Riemann[15]) is as contestable as its pendant in language, where there can be even one-word-phrases (like "Stop!" or "Hi!"). Thus no strict line can be drawn between the terms of the 'phrase', the 'motiv' or even the separate tone (as a one-tone-, one-chord- or one-noise-expression).

Thus, in views of Gestalt theory, the term of 'phrase' is rather enveloping any musical expression which is perceived as a consistent gestalt separate from others, however few or many beats, i. e. distinct musical events like tones, chords or noises, it may contain.

A phrase-group is "a group of three or more phrases linked together without the two-part feeling of a period", or "a pair of consecutive phrases in which the first is a repetition of the second or in which, for whatever reason, the antecedent-consequent relationship is absent".[17]

Phrase rhythm is the rhythmic aspect of phrase construction and the relationships between phrases, and "is not at all a cut-and-dried affair, but the very lifeblood of music and capable of infinite variety. Discovering a work's phrase rhythm is a gateway to its understanding and to effective performance." The term was popularized by William Rothstein's Phrase Rhythm in Tonal Music.[18] Techniques include overlap, lead-in, extension, expansion, reinterpretation and elision.

A phrase member is one of the parts in a phrase separated into two by a pause or long note value, the second of which may repeat, sequence, or contrast with the first.[20] A phrase segment "is a distinct portion of the phrase, but it is not a phrase either because it is not terminated by a cadence or because it seems too short to be relatively independent".[19]

See also

References

- White 1976, p. 44.

- Benjamin, Thomas; Horvit, Michael; and Nelson, Robert (2003). Techniques and Materials of Music, p. 252. 7th edition. Thomson Schirmer. ISBN 0495500542.

- Cooper, Paul (1973). Perspectives in Music Theory, p. 48. Dodd, Mead, and Co. ISBN 0396067522.

- Kostka & Payne 1995, p. 162.

- Falk (1958), p. 11, Larousse; cited in Nattiez 1990, p. .

- 1980 New Grove; cited in Nattiez 1990, p.

- Benward & Saker 2003, p. 89.

- 1958 Encyclopédie Fasquelle; cited in Nattiez 1990, p. .

- Stein 2005, p. .

- White 1976, p. 34.

- Winold, Allen (1975). "Rhythm in Twentieth-Century Music", Aspects of Twentieth-Century Music. Wittlich, Gary (ed.). Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-049346-5.

- Burkhart, Charles. "The Phrase Rhythm of Chopin's A-flat Major Mazurka, Op. 59, No. 2"; cited in Stein 2005, p. .

- Larousse, Davie 1966, 19; cited in Nattiez 1990, p. .

- Larousse; cited in Nattiez 1990, p. .

- Hugo Riemann. System der musikalischen Rhythmik und Metrik (Leipzig, 1903)

- White 1976, pp. 43–44.

- White 1976, p. 46.

- Rothstein, William (1990). Phase Rhythm in Tonal Music. New York: Schirmer. p. . ISBN 978-0-02-872191-0.

- Kostka & Payne 1995, p. 158

- Benward & Saker 2003, p. 113.

Sources

- Benward, Bruce; Saker, Marilyn (2003). Music: In Theory and Practice. Vol. I (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- Kostka, Stefan; Payne, Dorothy (1995). Tonal Harmony (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0073000566.

- Nattiez, Jean-Jacques (1990). Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music (originally Musicologie générale et sémiologue, 1987). Translated by Carolyn Abbate. ISBN 0-691-02714-5.

- Stein, Deborah (2005). Engaging Music: Essays in Music Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517010-5.

- White, John D. (1976). The Analysis of Music. ISBN 0-13-033233-X.

Further reading

- How to Understand Music: A Concise Course in Musical Intelligence and Taste (1881) by William Smythe Babcock Mathews

- What We Hear in Music: A Course of Study in Music History and Appreciation (c. 1921) by Anne Shaw Faulkner